<Back to Index>

- Physicist Robert Boyle, 1627

- Painter Jan van de Cappelle, 1626

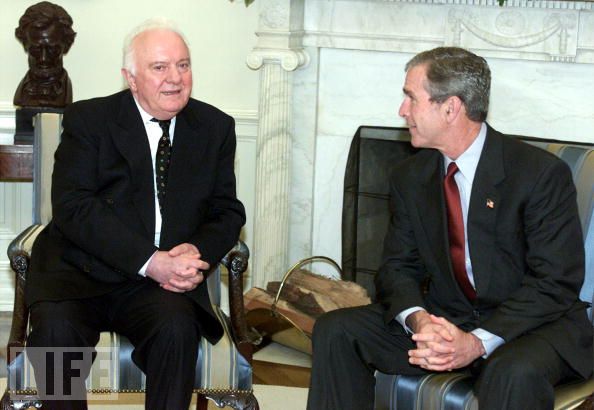

- 2nd President of Georgia Eduard Shevardnadze, 1927

PAGE SPONSOR

Eduard Shevardnadze (Georgian: ედუარდ შევარდნაძე; Russian: Эдуа́рд Амвро́сиевич Шевардна́дзе, Eduard Amvrosiyevich Shevardnadze; born 25 January 1927 / 28 is written in papers) served as the second President of Georgia from 1995 until he resigned on 23 November 2003 as a consequence of the bloodless Rose Revolution. Prior to his presidency, he served under Mikhail Gorbachev as the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Soviet Union from 1985 to 1991. Shevardnadze's political skills earned him the nickname of tetri melia (white fox).

Shevardnadze was born in Mamati, Lanchkhuti, Transcaucasian SFSR, Soviet Union. His father, a teacher, was very poor; he had a sister and three brothers, one of whom was killed in World War II. In 1937, during the Great Purge, his father, who had abandoned Menshevism for Bolshevism in the mid 1920s, was arrested but was released due to the intervention of an NKVD officer who had been his pupil. In 1951, Shevardnadze married Nanuli Tsagareishvili in a move he had been warned might wreck his career (her father had been executed as an "enemy of the people"); she died on 20 October 2004.

He joined the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1948 after two years as a Komsomol instructor and rose through the ranks to become a member of the Georgian Supreme Soviet in 1959. He was appointed Georgian Minister for the maintenance of public order in 1965 and subsequently became Georgian Minister for Internal Affairs from 1968 to 1972 with the rank of general in the police. He was appointed as General Secretary of the Georgian Communist Party by the Kremlin with the task of suppressing the grey and black-market capitalism that was growing in defiance of structure of the state and purge the local party ranks.

Shevardnadze

gained a reputation as a fierce opponent of corruption, which was

endemic in the republic, dismissing and imprisoning hundreds of

officials. One of his first reported acts was to call for a show of

hands by senior officials and promptly ordering all those displaying

expensive black-market watches to take them off and hand them in.

However, he never succeeded in entirely stamping out corruption. As

late as 1980, he found it necessary to reiterate that economic and

social development depended on "an uncompromising struggle against such

negative phenomena as money-grabbing, bribe-taking, misappropriation of

socialist property, private property tendencies, theft and other

deviations from the norms of communist morality." A corruption scandal in 1972 forced the resignation of Vasily Mzhavanadze,

the First Secretary of the Georgian Communist Party. His downfall may

have been precipitated by Shevardnadze, who was the natural replacement

candidate and was duly appointed to the post. During his time as First

Secretary, he continued to attack corruption and dealt firmly with

dissidents. In 1977, as part of a Soviet Union wide sweep against human

rights activists, his government imprisoned a number of prominent

Georgian dissidents on the grounds of anti-Soviet activities. These

included the leading dissidents Merab Kostava and Zviad Gamsakhurdia,

who later became the first democratically elected President of the

Republic of Georgia. On the other hand, he managed to gain from the

central authorities an unprecedented concession to the 1978 Georgian national movement in defense of the constitutional status of the Georgian language. Shevardnadze's hard line on corruption soon caught the attention of the Soviet hierarchy. He joined the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party in 1976 and in 1978 was promoted to the rank of candidate (non-voting) member of the Soviet Politburo.

He remained fairly obscure for a number of years, although he

consolidated a reputation for personal austerity, shunning the

trappings of high office and travelling to work by public transport

rather than using the limousines provided to Politburo members. His

chance came in 1985 when the veteran Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs, Andrei Gromyko, left that post for the largely ceremonial position of Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet. The de facto leader, Communist Party General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev,

appointed Shevardnadze to replace Gromyko as Minister of Foreign

Affairs, thus consolidating Gorbachev's circle of relatively young

reformers. He subsequently played a key role in the détente which marked the end of the Cold War. He was credited with helping to devise the so-called "Sinatra Doctrine"

of allowing the Soviet Union's eastern European satellites to "do it

their way" rather than forcibly restraining any attempts to pursue a

different course. When democratization and revolution began to sweep

across eastern Europe, he rejected the pleas of eastern European

Communist leaders for Soviet intervention and smoothed the path for a

(mostly) peaceful democratic transformation in the region. He

reportedly told hardliners that "it is time to realize that neither

socialism, nor friendship, nor good-neighborliness, nor respect can be

produced by bayonets, tanks or blood." However, his moderation was seen

by some communists and Russian nationalists as a betrayal and earned

him the long-term antagonism of powerful figures in Moscow. During

the late 1980s, as the Soviet Union descended into crisis, Gorbachev

and Shevardnadze became increasingly estranged from each other over

policy differences. Gorbachev fought to preserve a socialist government

and the unity of the Soviet Union, while Shevardnadze advocated further

political and economic liberalisation. He resigned in protest against

Gorbachev's policies in December 1990, delivering a dramatic warning to

the Soviet parliament that "Reformers have gone and hidden in the

bushes. Dictatorship is coming." A few months later, his fears were

partially realised when an unsuccessful coup by Communist hardliners

precipitated the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Shevardnadze returned briefly as Soviet Foreign Minister in November

1991 but resigned with Gorbachev the following month when the Soviet

Union was formally dissolved. In 1991, Shevardnadze was baptized into the Georgian Orthodox Church. The newly independent Republic of Georgia elected as its first president a leader of the nationalist movement, Zviad Gamsakhurdia,

a famous scientist and writer, who had been imprisoned by

Shevardnadze's government in the late 1970s. Gamsakhurdia's rule ended

abruptly in January 1992 when he was deposed in a bloody coup

d'état and forced to flee to the Chechen Republic in

neighboring Russia. Shevardnadze was appointed acting chairman of the

Georgian state council in March 1992. When the Presidency was restored

in November 1995, he was elected with 70% of the vote. He secured a

second term in April 2000 in an election that was marred by widespread

claims of vote-rigging. Shevardnadze's

career as Georgian President was in some respects even more challenging

than his earlier career as Soviet Foreign Minister. He faced many

enemies, some dating back to his campaigns against corruption and

nationalism in Soviet times. A civil war in western Georgia broke out

in 1993 between supporters of Gamsakhurdia and Shevardnadze but was

ended by Russian intervention on Shevardnadze's side and the death of

ex-President Gamsakhurdia on 31 December 1993. Three assassination

attempts were mounted against Shevardnadze. He escaped an assassination

attempt in Abkhazia in 1992: Russian military carried out an attack on

Shevardnadze's life. Then in August 1995 and February 1998 which his

government blamed on remnants of Gamsakhurdia's party. The 1995 attack

had seen his motorcade attacked with anti-tank rockets and small arms

fire in Tblisi under cover of night. He also faced separatist conflicts in the regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, which caused the deaths of an estimated 10,000 people, as well as an assertively autonomous government in Ajaria. The war in the Russian republic of Chechnya on Georgia's northern border caused considerable friction with Russia, which accused Shevardnadze of harbouring Chechen guerrillas

and supported Georgian separatists in apparent retaliation. Further

friction was caused by Shevardnadze's close relationship with the

United States, which saw him as a counterbalance to Russian influence

in the strategic Transcaucasus region.

Under Shevardnadze's strongly pro-Western administration, Georgia

became a major recipient of U.S. foreign and military aid, signed a

strategic partnership with NATO and declared an ambition to join both

NATO and the European Union. Perhaps his greatest diplomatic coup was the securing of a $3 billion project to build a pipeline carrying oil from Azerbaijan to Turkey via Georgia. At the same time, however, Georgia suffered badly from the effects of crime and rampant corruption,

often perpetrated by well-connected officials and politicians.

Shevardnadze's closest advisers, including several members of his

family, exerted disproportionate economic power. It was estimated by

outside observers that Shevardnadze's inner circle controlled as much

as 70 per cent of the economy: his wife edited and wrote for one of the

country's major newspapers, his daughter was the director of a

television film studio and her husband founded one of the country's

leading mobile phone networks (with American funding). While Shevardnadze himself was not a conspicuous profiteer, he was accused by many Georgians of shielding corrupt supporters and using his powers of patronage to shore up his own position. Georgia acquired

an unenviable reputation as one of the world's most corrupt countries.

Eventually, even his American supporters grew tired of pouring money

into an apparent black hole. On

2 November 2003, Georgia held a parliamentary election that was widely

denounced as unfair by international election observers, as well as by

the U.N. and the U.S. government. The outcome sparked fury among many

Georgians, leading to mass demonstrations in the capital Tbilisi and

elsewhere. Protesters broke into Parliament on 21 November as the first

session of the new Parliament was beginning, forcing President

Shevardnadze to escape with his bodyguards. He later declared a state of emergency and insisted that he would not resign. Despite

growing tension, both sides publicly stated their wish to avoid any

violence, a particular concern given Georgia's turbulent post-Soviet

history. Nino Burjanadze,

speaker of the Georgian parliament, said she would act as president

until the situation was resolved. The leader of the opposition Mikhail Saakashvili stated

he would guarantee Shevardnadze's safety and support his return as

President provided he promised to call early presidential elections. On 23 November Shevardnadze met with the opposition leaders Mikheil Saakashvili and Zurab Zhvania to discuss the situation, in a meeting arranged by Russian Foreign Minister Igor Ivanov.

After this meeting, the president announced his resignation, declaring

that he wished to avert a bloody power struggle "so all this can end

peacefully and there is no bloodshed and no casualties". However, it

was widely speculated that the refusal of the armed forces to enforce

his emergency decree was the main cause of his resignation. He claimed

the following day that he had been prepared to step down the previous

morning, hours before he actually did, but was prevented from doing so

by his entourage. Although

it was unclear precisely what role foreign powers played in the

toppling of Shevardnadze, it emerged shortly afterwards that both

Russia and the United States had played a direct role. U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell communicated

regularly with Shevardnadze during the post-election crisis, reportedly

pushing him to step down peacefully. Russian foreign minister Igor Ivanov flew to Tbilisi to visit three main opposition leaders and Shevardnadze, and arranged on late 23 November for Saakashvili and Zurab Zhvania to meet Shevardnadze. Ivanov then travelled to the autonomous region of Ajaria for consultations with the Ajaran leader Aslan Abashidze, who had been pro-Shevardnadze. Shevardnadze's

ouster prompted mass celebrations with drinking and dancing in the

streets by tens of thousands of Georgians crowding Tbilisi's Rustaveli Avenue and Freedom Square. The protesters dubbed their actions a "Rose Revolution", deliberately recalling the peaceful toppling of the Communist government in Czechoslovakia in the "Velvet Revolution" of 1989. Observers noted similarities with the overthrow of Yugoslav President Slobodan Milošević in 2000, who was also forced to resign by mass protests. The parallel with Yugoslavia was reinforced when it emerged that the Open Society Institute of George Soros had arranged contacts between the Georgian opposition and the Yugoslav Otpor (Resistance)

movement, which had been instrumental in the toppling of Milošević.

Otpor activists reportedly advised the Georgian opposition on the

methods that they had used to mobilize popular anger against Milošević.

According to the then editor-in-chief of The Georgian Messenger newspaper,

Zaza Gachechiladze, "It's generally accepted public opinion here that

Mr. Soros is the person who planned Shevardnadze's overthrow". IWPR reported

that on 28 November, in an interview held with the press at his home,

Shevardnadze "spoke with anger" about a plot by "unspecified Western

figures" to bring him down. He said that he did not believe that the US

administration was involved. The German government offered Shevardnadze political asylum in Germany, where he is still widely respected for his role as one of the chief Soviet architects of reunification in 1990. It was reported (although never confirmed) that his family had purchased a villa in the resort town of Baden-Baden.

However, he told German TV on 24 November, "Although I am very grateful

for the invitation from the German side, I love my country very much

and I won't leave it." He has begun to write his memoirs following his

enforced retirement. Shevardnadze's

political career was filled with contradictions. He was a product of

the Soviet system, but played a central role in dismantling that

system. He built his reputation on fighting political corruption, but

came to be seen as using corrupt methods to shore up his own position.

He achieved worldwide renown as the most liberal foreign minister in

the history of the USSR, but was never nearly as popular in his own

country. He succeeded in maintaining Georgia's territorial integrity in

the face of strong separatist pressures, but was unable to restore his

government's authority in large areas of the country. He helped to

establish a viable civil society in Georgia, but resorted to rigging

elections to maintain his powerbase. When Shevardnadze joined the Georgian state council in 1992 in the chaotic aftermath of the coup against Zviad Gamsakhurdia,

he presented himself as being the best candidate to guide Georgia

through its difficult rebirth as an independent nation. Over time, he

seemed to have become convinced that his interests and those of Georgia

were the same, justifying the use of unscrupulous tactics in the

apparent belief that Georgia could not survive without him. His

downfall ushered in a renewed period of uncertainty in Georgian

politics. One positive aspect in the eyes of many observers was the

fact that, under his rule, a vigorous civil society had become well

established and would possibly be better able to meet the challenge

than had been the case in the early 1990s. Shevardnadze published his memoirs in May 2006 under the title pikri tsarsulsa da momavalze, or 'Thoughts about the Past and the Future'. During the 2008 South Ossetia war, he made public his attempts to restore Georgian diplomatic relations with Russia, and continues to argue for it.