<Back to Index>

- Astronomer Johannes Hevelius, 1611

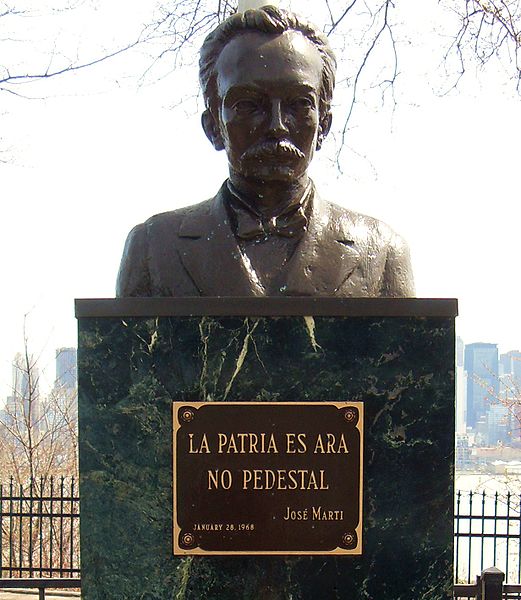

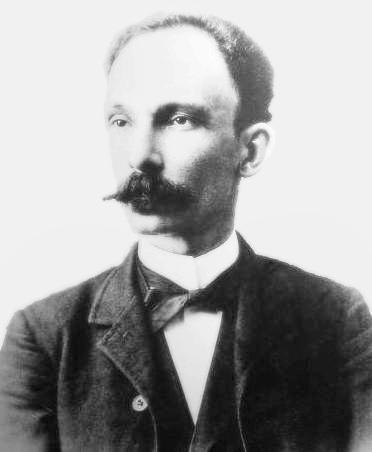

- Author and Cuban Revolutionary José Julián Martí Pérez, 1853

- 2nd Prime Minister of Canada Alexander Mackenzie, 1822

PAGE SPONSOR

José Julián Martí Pérez (January 28, 1853 – May 19, 1895) was a Cuban national hero and an important figure in Latin American literature. In his short life he was a poet, an essayist, a journalist, a revolutionary philosopher, a translator, a professor, a publisher, and a political theorist. Through his writings and political activity, he became a symbol for Cuba's bid for independence against Spain in the 19th century, and is referred to as the "Apostle of Cuban Independence." He also fought against the threat of United States expansionismin to Cuba. From adolescence, he dedicated his life to the promotion of liberty, political independence for Cuba and intellectual independence for all Spanish Americans; his murder was used as a cry for Cuban independence from Spain by both the Cuban revolutionaries and those Cubans previously reluctant to start a revolt.

Born in Havana, Martí began his political activism at a young age. He would travel extensively in Spain, Latin America, and the United States raising awareness and support for the cause of Cuban independence. His unification of the Cuban émigré community, particularly in Florida, was crucial to the success of the Cuban War of Independence against Spain. He was a key figure in the planning and execution of this war, as well as the designer of the Cuban Revolutionary Party and its ideology. He died in military action on May 19, 1895. Martí is considered one of the great turn-of-the-century Latin American intellectuals. His written works consist of a series of poems, essays, letters, lectures, a novel, and even a children's magazine. He wrote for numerous Latin American and American newspapers; he also founded a number of newspapers himself. His newspaper Patria was a key instrument in his campaign for Cuban independence. After his death, one of his poems from the book, "Versos Sencillos" (Simple Verses) was adapted to the song, "Guantanamera," which has become the definitive patriotic song of Cuba. The concepts of freedom, liberty, and democracy are prominent themes in all of his works, which were influential on the Nicaraguan poet, Rubén Darío and the Chilean poet, Gabriela Mistral.

José Julián Martí Pérez was born on January 28, 1853, in Havana, at 41 Paula St., to a Spanish Valencian father, Mariano Martí Navarro, and Leonor Pérez Cabrera, a native of the Canary Islands.

Martí was the elder brother to seven sisters: Leonor, Mariana,

Maria de Carmen, Maria de Pilar, Rita Amelia, Antonia and Dolores. He

was baptized on February 12 in Santo Ángel Custodio church. When

he was four, his family moved from Cuba to Valencia,

Spain, but two years later they returned to the island where they

enrolled José at a local public school, in the Santa Clara

neighborhood where his father worked as a prison guard. In

1865, he enrolled in the Escuela de Instrucción Primaria

Superior Municipal de Varones that was headed by Rafael María de

Mendive. Mendive was influential in the development of Martí's

political philosophies. Also instrumental in his development of a

social and political conscience was his best friend Fermín

Valdés Domínguez, the son of a wealthy slave-owning

family. In April the same year, after hearing the news of Abraham Lincoln's

assassination, Martí and other young students expressed their

pain — through group mourning — for the death of a man who had decreed the

abolition of slavery in a neighboring country. In 1866, Martí

entered the Instituto de Segunda Ensañanza where Mendive

financed his studies.

Martí

signed up at the Escuela Professional de Pintura y Escultura de La

Habana (Professional School for Painting and Sculpture of Havana) in

September 1867, known as San Alejandro, to take drawing classes. He

hoped to flourish in this area, but did not find commercial success. In

1867, he also entered the school of San Pablo, established and managed

by Mendive, where he enrolled for the second and third years of his

bachelor's degree, and assisted Mendive with the school's

administrative tasks. In April 1868, his poem dedicated to Mendive's

wife, A Micaela. En la muerte de Miguel Ángel appeared in Guanabacoa's newspaper El Álbum. When the Ten Years' War broke

out in Cuba in 1868, clubs of supporters for the Cuban nationalist

cause formed all over Cuba, and José and his friend

Fermín joined them. Martí had a precocious desire for the

independence and freedom of Cuba. He started writing poems about this

vision, while, at the same time, trying to do something to achieve this

dream. In 1869, he published his first political writings in the only

edition of the newspaper El Diablo Cojuelo, published by Fermín Valdés Domínguez. That same year he published "Abdala", a patriotic drama in verse form in the one-volume La Patria Libre newspaper, which he published himself. "Abdala" is about a fictional country called Nubia which struggles for liberation. His

famous sonnet "10 de octubre", later to become one of his most famous

poems, was also written during that year, and was published later in

his school newspaper. In

March of that year, colonial authorities shut down the school,

interrupting Martí's studies. He came to resent Spanish rule of

his homeland at a young age; likewise, he developed a hatred of slavery, which was still practiced in Cuba. On 21 October 1869, aged 16, he was arrested and incarcerated in the national jail, following an accusation of treason and

bribery from the Spanish government upon the discovery of a

"reproving" letter, which Martí and Fermín had written to

a friend when he joined the Spanish army. More

than four months later, Martí confessed to the charges and was

condemned to six years in prison. His mother tried to free her son (who

at 16 was still a minor) by writing letters to the government; his

father went to a lawyer friend for legal support, but all efforts

failed. Eventually Martí fell ill; his legs were severely

lacerated by the chains that bound him. As a result, he was transferred

to another part of Cuba known as Isla de Pinos instead of further imprisonment. Following that, the Spanish authorities decided to repatriate him to Spain. In

Spain, Martí, who was 18 at the time, was allowed to continue

his studies with the hopes that studying in Spain would renew his

loyalty to Spain. In January 1871, Martí embarked on the steam ship Guipuzcoa,

which took him from Havana to Cadiz. He settled in Madrid in a

guesthouse in Desengaño St. # 10. Arriving at the capital he

contacted fellow Cuban Carlos Sauvalle, who had been deported to Spain

a year before Martí and whose house served as a center of

reunions for Cubans in exile. On March 24, Cadiz’s newspaper La Soberania Nacional,

published Martí's article “Castillo” in which he recalled the

sufferings of a friend he met in prison. This article would be

reprinted in Sevilla’s La Cuestion Cubana and New York’s La Republica.

At this time, Martí registered himself as a member of

independent studies in the law faculty of the Central University of

Madrid. While

studying here, Martí openly participated in discourse on the

Cuban issue, debating through the Spanish press and circulating

documents protesting Spanish activities in Cuba. Martí's maltreatment at the hands of the Spaniards and consequent deportation to Spain in 1871 inspired a tract, Political Imprisonment in Cuba,

published in July. This pamphlet's purpose was to move the Spanish

public to do something about its government's brutalities in Cuba and

promoted the issue of Cuban independence. In September, from the pages of El Jurado Federal, Marti and Sauvalle accused the newspaper La Prensa of having calumniated the Cuban residents in Madrid. During his stay in Madrid, Marti frequented the Ateneo and the National Library, the Café de los Artistas, and the British, Swiss and Iberian breweries. In November he became sick and had an operation, paid for by Sauvalle. On

the 27 of November 1871, eight medical students, who had been accused

(without evidence) of the desecration of a Spanish grave, were executed

in Havana. In June 1872, Fermín Valdés was arrested because of the November 27 incident.

His six years of jail were pardoned and he was exiled to Spain where he

reunited with Martí. On November 27, 1872, the printed matter Dia 27 de Noviembre de 1871 (27

November 1871) written by Martí and signed by Fermín

Valdés Domínguez, and Pedro J. de la Torre circulated in

Madrid. A group of Cubans held a funeral in the Caballero de Gracia

church, the first anniversary of the medical students’ execution. In 1873, Martí's “A mis Hermanos Muertos el 27 de Noviembre” was

published by Fermín Valdés. In February, for the first

time, the Cuban flag appeared in Madrid, hanging from Martí’s

balcony in Concepción Jerónima, where he lived for a few

years. In the same month, the Proclamation of the First Spanish

Republic by the Cortes on February 11, 1873 reaffirmed Cuba as

inseparable to Spain, Martí responded with an essay, The Spanish Republic and the Cuban Revolution,

and sent it to the Prime Minister, pointing out that this new freely

elected body of deputies that had proclaimed a republic based on

democracy had been hypocritical not to grant Cuba its freedom. He

sent examples of his work to Nestor Ponce de Leon, a member of the

Junta Central Revolucionaria de Nueva York (Central revolutionary

committee of New York), to whom he would express his will to

collaborate on the fight for the independence of Cuba. In

May, he moved to Zaragoza, accompanied by Fermín Valdés

to continue his studies in law at the Universidad Literaria. The

newspaper La Cuestión Cubana of Sevilla, published numerous articles from Martí. In

June 1874, Marti graduated with a degree in Civil Rights and Canonical

Law. In August he signed up as an external student at the Facultad de Filosofia y Letras de Zaragoza,

where he finished his degree by October. In November he returned to

Madrid and then left to Paris. There he met Auguste Vacquerie, a poet,

and Victor Hugo. In December 1874 he embarked from Le Havre for Mexico. Prevented from returning to Cuba, Martí went instead to Mexico and

Guatemala. During these travels, he taught and wrote, advocating continually for Cuba's independence. In 1875, Martí lived on Calle Moneda in Mexico City near the Zócalo, a prestigious address of the times. One floor above him lived Manuel Mercado, Secretary of the Distrito Federal, who would become one of Martí’s best friends. On March 2, 1875, he published his first article for Vicente Villada's Revista Universal,

a broadsheet discussing politics, literature, and general business

commerce. On March 12, his Spanish translation of Victor Hugo's Mes Fils (1874) began serialization in Revista Universal. Martí then joined the editorial staff, editing the Boletín section

of the publication. In these writings he expressed his opinions about

current events in Mexico. On May 27, in the newspaper Revista Universal, he responded to the anti Cuban independence arguments in the Mexican newspaper La Colonia Española. In December, Sociedad Gorostiza (Gorostiza Society), a group of writers and artists, accepted Martí as a member, where he met his future wife, Carmen Zayas Bazán during his frequent visits to her Cuban father’s house to meet with the Gorostiza group. On January 1, 1876, in Oaxaca, elements contrary to Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada's government led by Gen. Porfirio Díaz proclaimed the Plan de Tuxtepec,

thence instigating a bloody civil war. Martí and fellow Mexican

colleagues established the Sociedad Alarcón, composed of

dramatists, actors, and critics. At this point, Martí began

collaboration with the newspaper El Socialista as

leader of the Gran Círculo Obrero (Great Labour Circle)

organization of liberals and reformists who supported Lerdo de Tejada.

In March, the newspaper proposed a series of candidates as delegates,

including Martí, to the first Congreso Obrero, or congress of

the workers. On June 4, La Sociedad Esperanza de Empleados (Employees'

Hope Society) designated Martí as delegate to the Congreso

Obrero. On December 7, Martí published his article Alea Jacta Est in the newspaper El Federalista,

bitterly criticizing the Porfiristas' armed assault upon the

constitutional government in place. On December 16, he published the

article "Extranjero" (foreigner; abroad), in which he repeated his

denunciation of the Porfiristas and bade farewell to Mexico. In 1877, using his second name and second surname Julián

Pérez as pseudonym, Martí embarked for Havana, hoping to

there arrange moving his family away from Mexico City. He returned to

Mexico, however, entering at the port of Progreso from which, via Isla de Mujeres and Belize, he travelled south to progressive Guatemala City. He took residence in the prosperous suburb of Ciudad Vieja, home of Guatemala's artists and Intelligentsia of the day, on Cuarta

Avenida (fourth avenue), 3 km south of Guatemala City. Commissioned then by the government, he wrote the play Patria y Libertad (Drama Indio) (Country and Liberty (an Indian Drama)). He met personally the president, Justo Rufino Barrios about this project. On April 22, the newspaper El Progreso published his article "Los códigos nuevos" (The

New Laws) pertaining to the then newly enacted Civil Code. On May 29,

he was appointed head of the Department of French, English, Italian and

German Literature, History and Philosophy, on the faculty of philosophy

and arts of the Universidad Nacional.

On July 25, he lectured for the opening evening of the literary society

'Sociedad Literaria El Porvenir', at the Teatro Colón (the

since-renamed Teatro Nacional),

at which function he was appointed vice-president of the Society, and

acquiring the moniker "el doctor torrente," or Doctor Torrent, in view

of his rhetorical style. Martí taught composition classes free

at the academia de niñas de centroamérica girls' academy, among whose students he enthralled young María García Granados, daughter of Guatemalan president Miguel García Granados.

The schoolgirl's crush was unrequited, however, as he went again to

México, where he met Carmen Zayas Bazán and whom he later

married. In 1878, Martí returned to Guatemala and published his book Guatemala,

edited in Mexico. On May 10, socialite María García

Granados died of lung disease; her unrequited love for Martí

branded her, poignantly, as 'la niña de Guatemala, la que se

murió de amor' (the Guatemalan girl who died of love). Following

her death, Martí returned to Cuba. There, he finished signing the Pact of Zanjón which ended the Cuban Ten Years' War, but had no effect on Cuba's status as a colony. During this same journey he married Carmen Zayas Bazán on Havana's Calle Tulipán Street.

In October, his application to practice law in Cuba was refused, and

thence immersed himself in radical efforts, such as for the Comité Revolucionario Cubano de Nueva York (Cuban

Revolutionary Committee of New York). On November 2, 1878 his son

José Francisco, known fondly as "Pepito", was born. After a short time in New York, Martí travelled to Venezuela in 1881 and founded the Revista Venezolana,

or Venezuelan Review. The journal provoked the wrath of Venezuela's

dictator, Antonio Guzmán Blanco, and Martí was forced to

leave for New York. Back in New York Martí joined General Calixto García's

Cuban revolutionary committee, made up of exiled & disheveled

Cubans who wanted independence for Cuba. Here Martí supported

Cuban independence freely. He worked as a newspaper reporter and was

also a correspondent for La Nación of Buenos Aires and for different Central American journals, especially La Opinion Liberal in Mexico City. The article "El ajusticiamiento de Guiteau," an account of President Garfield's murderer's trial, was published in La Opinion Liberal in 1881, and later selected for inclusion in The Library of America's

anthology of American True Crime writing. At the same time,

Martí wrote poems and translated novels to Spanish. He worked

for Appleton and Company and, "on his own, translated and published

Helen Hunt Jackson's Ramona. His repertory of original work included plays, a novel, poetry, a children's magazine, La Edad de Oro, and a newspaper, Patria, which became the official organ of the Cuban Revolutionary party". Also,

he worked very hard by serving as a consul for Uruguay, Argentina, and

Paraguay. Throughout this work, he preached the "freedom of Cuba with

an enthusiasm that swelled the ranks of those eager to strive with him

for it". Within

the revolutionary committee, there was tension between Martí and

his Cuban military compatriots. Martí thought it was of utmost

importance that a military dictatorship not be established in Cuba upon

independence, and suspected Dominican-born General Máximo Gómez of having these very intentions. Martí

knew that the independence of Cuba needed careful planning and would

take time. This is why Martí refused to cooperate with Máximo Gómez and Antonio Maceo Grajales, two Cuban military leaders from the Ten Years' War,

when they wanted to invade immediately in 1884. Martí knew that

it was too early to attempt to win back Cuba, and later events proved

him right. On January 1, 1891, Martí's essay "Nuestra America" was published in New York's Revista Ilustrada, and on the 30th of that month in Mexico's El Partido Liberal.

He actively participated in the Conferencia Monetaria Internacional

(The International Monetary Conference) in New York during that time as

well. On June 30 his wife and son arrived in New York. After a short

time, in which Carmen Zayas Bazán realized that Martí's

dedication to Cuban independence surpassed that of supporting his

family, she returned to Havana with her son on 27 August. Martí

would never see them again. The fact that his wife never shared the

convictions central to his life was an enormous personal tragedy for

Martí. He

turned for solace to Carmen Miyares de Mantilla, a Venezuelan who ran a

boarding house in New York, and he is presumed to be the father of her

daughter María Mantilla, who was in turn the mother of the actor Cesar Romero,

who proudly claimed to be Martí's grandson. In September

Martí became sick again. He intervened in the commemorative acts

of The Independents, causing the Spanish consul in New York to complain

to the Argentine and Uruguayan governments. Consequently, Martí

resigned from the Argentinean, Paraguayan, and Uruguayan consulates. In

October he published his book Versos Sencillos. On the 26 of November, he was invited by the Club Ignacio Agramonte of Tampa, Florida, to a celebration to collect funding for the cause of Cuban independence. There he gave a lecture known as "Con Todos, y para el Bien de Todos". The following night, another lecture, " Los Pinos Nuevos",

was given by Martí in a gathering in honor of the medical

students killed in 1871. In November artist Herman Norman painted a

portrait of José Martí. On January 5, 1892, Martí participated in a reunion of the emigration representatives, in Cayo Hueso, where the Bases del Partido Revolucionario (Basis

of the Cuban Revolutionary Party) was passed. He began the process of

organizing the newly formed party. To raise support and collect funding

for the independence movement, he visited tobacco factories, where he

gave speeches to the workers and united them in the cause. In March

1892 the first edition of the Patria newspaper,

related to the Cuban Revolutionary Party, was published, funded and

directed by Martí. On April 8, he was chosen delegate of the

Cuban Revolutionary Party by the Cayo Hueso Club in Tampa and New York.

From July to September 1892 he traveled through Florida, Washington,

Philadelphia, Haiti, the Dominican Republic and Jamaica on an

organization mission among the exiled Cubans. On this mission,

Martí made numerous speeches and visited various tobacco

factories. On December 16 he was poisoned in Tampa. In

1893, Marti traveled through the United States, Central America and the

West Indies, visiting different Cuban clubs. His visits were received

with a growing enthusiasm and raised badly needed funds for the

revolutionary cause. On May 24 he met Rubén Darío, the Nicaraguan poet in a theatre act in Hardman Hall, New Mexico. On June 3 he had an interview with Máximo Gómez in Montecristi, Dominican Republic, where they planned the uprising. In July he met with General Antonio Maceo Grajales in San Jose, Costa Rica. In 1894 he continued traveling for propagation and organizing the revolutionary movement. On January 27 he published "A Cuba!" in the newspaper Patria where

he denounced collusion between the Spanish and American interests. In

July he visited the president of the Mexican Republic, Porfirio Díaz, and travelled to Veracruz. In August he prepared and arranged the armed expedition that would begin the Cuban revolution. January 12, 1895, the North American authorities stopped the steamship Lagonda and two other suspicious ships, Amadis, and Baracoa at

the Fernandina port in Florida, confiscating weapons and ruining Plan

de Fernandina (Fernandina Plan). On January 29, Martí drew up

the order of the uprising, signing it with general Jose Maria Rodriguez

and Enrique Collazo. They decided to move to Montecristi, to join Máximo Gómez and to plan out the uprising. Martí

had persuaded Gómez to lead an expedition into Cuba. The

expedition finally took place on February 24, 1895. A month later,

Martí and Gómez declared the Manifesto de Montecristi, an

"exposition of the purposes and principles of the Cuban revolution".

Before leaving for Cuba, Martí wrote his "literary will" on

April 1, 1895, leaving his personal papers and manuscripts to Gonzalo de Quesada,

with instructions for editing. Knowing that the majority of his writing

in newspapers in Honduras, Uruguay, and Chile would dissipate,

Martí instructed Quesada to arrange his papers in volumes. The

volumes were to be arranged in the following way: volumes one and two,

North Americas; volume three, Hispanic Americas; volume four, North

American Scenes; volume five, Books about the Americas (this included

both North and South America); volume six, Literature, education and

painting. Another volume included his poetry. The

expedition, composed of Martí, Gómez, Ángel

Guerra, Francisco Borreo, Cesar Salas and Marcos del Rosario, left

Montecristi for Cuba on April 1, 1895. Despite

delays and desertion by some members, they got to Cuba. They landed at

Playitas, near Maisi Cape, Cuba, on April 11. Once there, they made

contact with the Cuban rebels, who were headed by the Maceo brothers,

and started fighting against Spanish troops. By May 13, the expedition

reached Dos Rios. On May 19, Gomez faced Ximenez de Sandoval's troops

and ordered Martí to stay rearguard, but Martí separated

from the bulk of the Cuban forces, and entered the Spanish line. José Martí was killed in battle against Spanish troops at the Battle of Dos Ríos, near the confluence of the rivers Contramaestre and Cauto,

on May 19, 1895. Gómez had recognized that the Spaniards had a

strong position between palm trees, so he ordered his men to disengage.

Martí was alone and seeing a young courier ride by he said:

"Joven, a la carga" meaning: "Young man, let's charge!" This was around

midday, and he was, as always, dressed in a black jacket, riding a

white horse, which made him an easy target for the Spanish. The young

trooper, Angel de la Guardia, lost his horse and returned to report the

loss. The Spanish took possession of the body, buried it close by, then

exhumed the body upon realization of its identity. They are said not to

have burned him because they were scared that the ashes would get into

their throats and asphyxiate them. He is buried in Cementerio Santa

Efigenia in Santiago de Cuba.

Many have argued that Maceo and others had always spurned Martí

for never participating in combat, which may have compelled

Martí to that ill-fated suicidal two-man charge. Some of his Versos sencillos bore

premonition: "No me entierren en lo oscuro/ A morir como un traidor/ Yo

soy bueno y como bueno/ Moriré de cara al sol." ("Do not bury me

in darkness / to die like a traitor / I am good, and as a good man / I

will die facing the sun.") The

death of Marti was a blow to the "aspirations of the Cuban rebels,

inside and outside of the island, but the fighting continued with

alternating successes and failures until the entry of the United States

into the war in 1898".