<Back to Index>

- Aviation Pioneer Jean Pierre Blanchard, 1753

- Songwriter Sthephen Collins Foster, 1826

- 30th President of the United States John Calvin Coolidge, Jr., 1872

PAGE SPONSOR

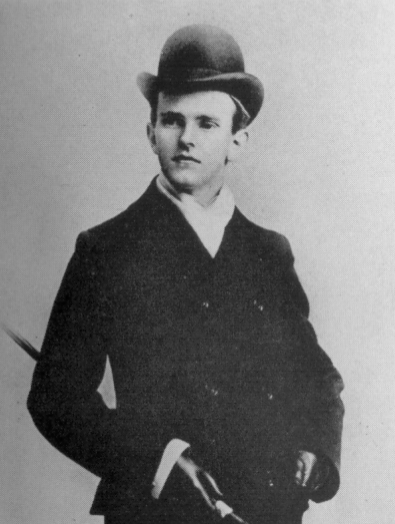

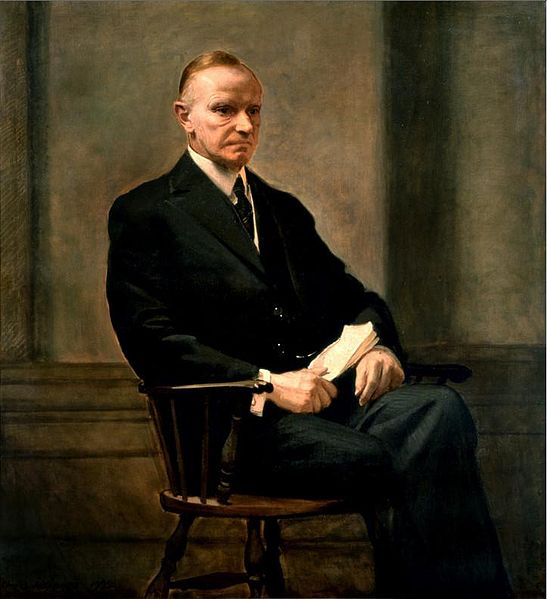

John Calvin Coolidge, Jr. (July 4, 1872 – January 5, 1933) was the 30th President of the United States (1923 – 1929). A Republican lawyer from Vermont, Coolidge worked his way up the ladder of Massachusetts state politics, eventually becoming governor of that state. His actions during the Boston Police Strike of 1919 thrust him into the national spotlight. Soon after, he was elected as the 29th Vice President in 1920 and succeeded to the Presidency upon the sudden death of Warren G. Harding in 1923. Elected in his own right in 1924, he gained a reputation as a small-government conservative.

Coolidge restored public confidence in the White House after the scandals of his predecessor's administration, and left office with considerable popularity. As a Coolidge biographer put it, "He embodied the spirit and hopes of the middle class,

could interpret their longings and express their opinions. That he did

represent the genius of the average is the most convincing proof of his

strength." Many later criticized Coolidge as part of a general criticism of laissez-faire government. His reputation underwent a renaissance during the Ronald Reagan Administration, but

the ultimate assessment of his presidency is still divided between

those who approve of his reduction of the size of government programs

and those who believe the federal government should be more involved in

regulating and controlling the economy. John Calvin Coolidge, Jr., was born in Plymouth Notch, Windsor County, Vermont, on July 4, 1872, the only U.S. President to be born on the Fourth of July. He was the elder of the two children of John Calvin Coolidge, Sr. (1845 – 1926)

and Victoria Josephine Moor (1846 – 1885). Calvin Coolidge's chronically

ill mother died, perhaps from tuberculosis, when he was just twelve

years old. His sister, Abigail Grace Coolidge (1875 – 1890), died at the

age of fifteen, when he was eighteen. Calvin Coolidge's father

remarried in 1891, to a schoolteacher, and lived to the age of eighty.

Over the years, Coolidge grew close to his stepmother. Coolidge's

father engaged in many occupations during his lifetime, and ultimately

enjoyed a statewide reputation as a prosperous farmer, storekeeper and

committed public servant;

he farmed, taught school, ran a local store, served in the Vermont

House of Representatives and the Vermont Senate, and held various local

offices including justice of the peace and tax collector. Coolidge's mother was the daughter of a Plymouth Notch farmer. Coolidge's family had deep roots in New England. His earliest American ancestor, John Coolidge, emigrated from Cambridge, England, around 1630 and settled in Watertown, Massachusetts. Another ancestor, Edmund Rice, arrived at Watertown in 1638. Coolidge's great-great-grandfather, also named John Coolidge, was an American military officer in the Revolutionary War and one of the first selectmen of the town of Plymouth Notch. Most of Coolidge's ancestors were farmers. Better-known Coolidges, architect Charles Allerton Coolidge, General Charles Austin Coolidge, and diplomat Archibald Cary Coolidge among them, were descended from branches of the family that had remained in Massachusetts. Coolidge's grandmother Sarah Almeda Brewer had two famous first cousins: Arthur Brown, a United States Senator, and Olympia Brown, a women's suffragist. It is through this ancestor that Coolidge claimed American Indian blood, but this descent has not been established. Coolidge's

grandfather, Calvin Coolidge, held offices in the local government of

Plymouth and was remembered as a man with "a fondness for practical

jokes".

Coolidge attended Black River Academy and then Amherst College, where he joined the Phi Gamma Delta fraternity. At his father's urging, Coolidge moved to Northampton, Massachusetts, after graduating to take up the practice of law. Avoiding the costly alternative of attending a law school,

Coolidge followed the more common practice of the time, apprenticing

with the firm of a local law firm, Hammond & Field, and reading law with

them. John C. Hammond and Henry P. Field, both Amherst graduates,

introduced Coolidge to the law practice in the county seat of Hampshire County. In 1897, Coolidge was admitted to the bar, becoming a country lawyer.

With his savings and a small inheritance from his grandfather, Coolidge

was able to open his own law office in Northampton in 1898. He

practiced transactional law, believing that he served his clients best

by staying out of court. As his reputation as a hard-working and

diligent attorney grew, local banks and other businesses began to

retain his services. In 1905 Coolidge met and married a fellow Vermonter, Grace Anna Goodhue, who was working as a teacher at the Clarke School for the Deaf.

While Grace was watering flowers outside the school one day in 1903,

she happened to look up at the open window of Robert N. Weir's

boardinghouse and caught a glimpse of Calvin Coolidge shaving in front

of a mirror with nothing on but long underwear and a hat. After a more formal introduction sometime later, the two were quickly attracted to each other. They were married on October 4, 1905, in the parlor of her parents' home in Burlington, Vermont. They were opposites in personality: she was talkative and fun-loving, while he was quiet and serious. Not

long after their marriage, Coolidge handed her a bag with fifty-two

pairs of socks in it, all of them full of holes. Grace's reply was "Did

you marry me to darn your socks?" Without cracking a smile and with his

usual seriousness, Calvin answered, "No, but I find it mighty handy." They had two sons: John, born in 1906, and Calvin, Jr., born in 1908. The marriage was , by most accounts, a happy one. As Coolidge wrote in his Autobiography,

"We thought we were made for each other. For almost a quarter of a

century she has borne with my infirmities, and I have rejoiced in her

graces."

The Republican Party was

dominant in New England in Coolidge's time, and he followed Hammond's

and Field's example by becoming active in local politics. Coolidge campaigned locally for Republican presidential candidate William McKinley in 1896, and the next year he was selected to be a member of the Republican City Committee. In 1898, he won election to the City Council of Northampton, placing second in a ward where the top three candidates were elected. The position offered no salary, but gave Coolidge experience in the political world. In 1899, he declined renomination, running instead for City Solicitor, a position elected by the City Council. He was elected for a one year term in 1900, and reelected in 1901. This position gave Coolidge more experience as a lawyer, and paid a salary of $600. In 1902, the city council selected a Democrat for city solicitor, and Coolidge returned to an exclusively private practice. Soon thereafter, however, the clerk of courts for

the county died, and Coolidge was chosen to replace him. The position

paid well, but barred him from practicing law, so he only remained at

the job for one year. The next year, 1904, Coolidge met with his only defeat before the voters, losing an election to the Northampton school board.

When told that some of his neighbors voted against him because he had

no children in the schools he would govern, Coolidge replied "Might

give me time!" In 1906 the local Republican committee nominated Coolidge for election to the state House of Representatives. He won a close victory over the incumbent Democrat, and reported to Boston for the 1907 session of the Massachusetts General Court. In his freshman term, Coolidge served on minor committees and, although he usually voted with the party, was known as a Progressive Republican, voting in favor of such measures as women's suffrage and the direct election of Senators. Throughout his time in Boston, Coolidge found himself allied primarily with the western Winthrop Murray Crane faction of the state Republican Party, as against the Henry Cabot Lodge dominated eastern faction. In

1907, he was elected to a second term. In the 1908 session, Coolidge

was more outspoken, but was still not one of the leaders in the

legislature. Instead of vying for another term in the state house, Coolidge returned home to his growing family and ran for mayor of

Northampton when the incumbent Democrat retired. He was well-liked in

the town, and defeated his challenger by a vote of 1,597 to 1,409. During

his first term (1910 to 1911), he increased teachers' salaries and

retired some of the city's debt while still managing to effect a slight

tax decrease. He was renominated in 1911, and defeated the same opponent by a slightly larger margin. In 1911, the State Senator for

the Hampshire County area retired and encouraged Coolidge to run for

his seat for the 1912 session. He defeated his Democratic opponent by a

large margin. At the start of that term, Coolidge was selected to be chairman of a committee to arbitrate the "Bread and Roses" strike by the workers of the American Woolen Company in Lawrence, Massachusetts. After two tense months, the company agreed to the workers' demands in a settlement the committee proposed. The other major issue for Republicans that year was the party split between the progressive wing, which favored Theodore Roosevelt, and the conservative wing, which favored William Howard Taft. Although he favored some progressive measures, Coolidge refused to leave the Republican party. When the new Progressive Party declined

to run a candidate in his state senate district, Coolidge won

reelection against his Democratic opponent by an increased margin. The

1913 session was less eventful, and Coolidge's time was mostly spent on

the railroad committee, of which he was the chairman. Coolidge intended to retire after the 1913 session, as two terms were the norm, but when the President of the State Senate, Levi H. Greenwood, considered running for Lieutenant Governor, Coolidge decided to run

again for the Senate in the hopes of being elected as its presiding officer. Although

Greenwood later decided to run for reelection to the Senate, he was

defeated and Coolidge was elected, with Crane's help, as the President

of a closely divided Senate. After his election in January 1914, Coolidge delivered a speech entitled Have Faith in Massachusetts, which summarized his philosophy of government. It was later published in a book, and frequently quoted. Coolidge's speech was well-received and he attracted some admirers on its account. Towards

the end of the term, many of them were proposing his name for

nomination to lieutenant governor. After winning reelection to the

Senate by an increased margin in the 1914 elections, Coolidge was

reelected unanimously to be President of the Senate. As the 1915 session ended, Coolidge's supporters, led by fellow Amherst alumnus Frank Stearns, encouraged him again to run for lieutenant governor. This time, he accepted their advice. Coolidge entered the primary election for lieutenant governor and was nominated to run alongside gubernatorial candidate Samuel W. McCall. Coolidge was the leading vote-getter in the Republican primary, and balanced the Republican ticket by adding a western presence to McCall's eastern base of support. McCall and Coolidge won the 1915 election, with Coolidge defeating his opponent by more than 50,000 votes. Coolidge's

duties as lieutenant governor were few; in Massachusetts, the

lieutenant governor does not preside over the state Senate, although

Coolidge did become an ex officio member of the governor's cabinet. As

a full-time elected official, Coolidge no longer practiced law after

1916, though his family continued to live in Northampton. McCall

and Coolidge were both reelected in 1916 and again in 1917 (both

offices were one-year terms in those days). When McCall decided that he

would not stand for a fourth term, Coolidge announced his intention to

run for governor.

Coolidge was unopposed for the Republican nomination for Governor of Massachusetts in 1918. He and his running mate, Channing Cox, a Boston lawyer and Speaker of the Massachusetts House of Representatives, ran on the previous administration's record: fiscal conservatism, a vague opposition to Prohibition, support for women's suffrage, and support for American involvement in the First World War. The issue of the war proved divisive, especially among Irish- and German-Americans. Coolidge

was elected by a margin of 16,773 votes over his opponent, Richard H.

Long, in the smallest margin of victory of any of his state wide

campaigns.

In 1919, in response to rumors that policemen of the Boston Police Department planned to form a union, Police Commissioner Edwin U. Curtis issued a statement saying that such a move would not be tolerated. In August of that year, the American Federation of Labor issued a charter to the Boston Police Union. Curtis

said the union's leaders were insubordinate and planned to relieve them

of duty, but said that he would suspend the sentence if the union was

dissolved by September 4. The mayor of Boston, Andrew Peters, convinced Curtis to delay his action for a few days, but Curtis ultimately suspended the union leaders on September 8. The following day, about three quarters of the policemen in Boston went on strike. Coolidge

had observed the situation throughout the conflict, but had not yet

intervened. That night and the next, there was sporadic violence and rioting in the lawless city. Peters, concerned about sympathy strikes, had called up some units of the Massachusetts National Guard stationed in the Boston area and relieved Curtis of duty. Coolidge, furious that the mayor had called out state guard units, finally acted. He called up more units of the National Guard, restored Curtis to office, and took personal control of the police force. Curtis

proclaimed that all of the strikers were fired from their jobs, and

Coolidge called for a new police force to be recruited. That night Coolidge received a telegram from AFL leader Samuel Gompers.

"Whatever disorder has occurred", Gompers wrote, "is due to Curtis's

order in which the right of the policemen has been denied …" Coolidge publicly answered Gompers's telegram with the response that would

launch him into the national consciousness. Newspapers

across the nation picked up on Coolidge's statement and he became the

newest hero to defenders of the public's safety and security. In the midst of the First Red Scare, many Americans were terrified of the spread of communist revolution, like those that had taken place in Russia, Hungary, and Germany. While Coolidge had lost some friends among organized labor, conservatives across the nation had seen a rising star.

Coolidge

and Cox were renominated for their respective offices in 1919. By this

time Coolidge's supporters (especially Stearns) had publicized his

actions in the Police Strike around the state and the nation and some

of Coolidge's speeches were published in book form. He was faced with the same opponent as in 1918, Richard Long, but this

time Coolidge defeated him by 125,101 votes, more than seven times his

margin of victory from a year earlier. His

actions in the police strike, combined with the massive electoral

victory, led to suggestions that Coolidge should run for President in

1920. By

the time Coolidge was inaugurated on January 2, 1919, the First World

War had ended, and Coolidge pushed the legislature to give a $100 bonus

to Massachusetts veterans. He also signed a bill reducing the work week

for women and children from fifty-four hours to forty-eight, saying, "We must humanize the industry, or the system will break down." He

signed into law a budget that kept the tax rates the same, while

trimming four million dollars from expenditures, thus allowing the

state to retire some of its debt. Coolidge also wielded the veto pen as governor. His most publicized veto was of a bill that would have increased legislators' pay by 50%. Although

Coolidge was personally opposed to Prohibition, he vetoed a bill in May

1920 that would have allowed the sale of beer or wine of 2.75% alcohol or less, in Massachusetts in violation of the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. "Opinions and instructions do not outmatch the Constitution," he said in his veto message, "Against it, they are void." At the 1920 Republican Convention most

of the delegates were selected by state party conventions, not

primaries. As such, the field was divided among many local favorites. Coolidge

was one such candidate, and while he placed as high as sixth in the

voting, the powerful party bosses never considered him a serious

candidate. After ten ballots, the delegates settled on Senator Warren G. Harding of Ohio as their nominee for President. When

the time came to select a Vice Presidential nominee, the party bosses

had also made a decision on who they would nominate: Senator Irvine Lenroot of Wisconsin. A delegate from Oregon, Wallace McCamant, having read Have Faith in Massachusetts, proposed Coolidge for Vice President instead. The suggestion caught on quickly, and Coolidge found himself unexpectedly nominated. The Democrats nominated another Ohioan, James M. Cox, for President and the Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Franklin D. Roosevelt, for Vice President. The question of the United States joining the League of Nations was a major issue in the campaign, as was the unfinished legacy of Progressivism. Harding ran a "front-porch" campaign from his home in Marion, Ohio, but Coolidge took to the campaign trail in the Upper South, New York, and New England. On November 2, 1920, Harding and Coolidge were victorious in a landslide, winning every state outside the South. They also won in Tennessee, the first time a Republican ticket had won a Southern state since Reconstruction. The

Vice-Presidency did not carry many official duties, but Coolidge was

invited by President Harding to attend cabinet meetings, making him the

first Vice President to do so. He gave speeches around the country, but none was especially noteworthy. As Vice-President, Coolidge and his vivacious wife Grace were

invited to quite a few parties, where the legend of "Silent Cal" was

born. It was from this time most of the jokes and anecdotes involving

Coolidge originate. Although Coolidge was known to be a skilled and

effective public speaker, in private he was a man of few words and was

therefore commonly referred to as "Silent Cal." A possibly apocryphal

story has it that Dorothy Parker,

seated next to him at a dinner, said to him, "Mr. Coolidge, I've made a

bet against a fellow who said it was impossible to get more than two

words out of you." His famous reply: "You lose." It was also Parker who, upon learning that Coolidge had died, reportedly remarked, "How can they tell?" Alice Roosevelt Longworth supposedly once commented that, "He looks as if he'd been weaned on a pickle." Coolidge

often seemed uncomfortable among fashionable Washington society; when

asked why he continued to attend so many of their dinner parties, he

replied, "Got to eat somewhere." As

President, Coolidge's reputation as a quiet man continued. "The words

of a President have an enormous weight," he would later write, "and ought not to be used indiscriminately." Coolidge

was aware of his stiff reputation; indeed, he cultivated it. "I think

the American people want a solemn ass as a President," he once told Ethel Barrymore,

"and I think I will go along with them." However, he did hold a then

record number of presidential press conferences, 520 during his

presidency. Some historians would later suggest that Coolidge's image was created deliberately as a campaign tactic, while others believe his withdrawn and quiet behavior to be natural, deepening after the death of his son in 1924.

On August 2, 1923, President Harding died while on a speaking tour in California. Vice-President Coolidge was in Vermont visiting his family home, which had neither electricity nor a telephone, when he received word by messenger of Harding's death. Coolidge dressed, said a prayer, and came downstairs to greet the reporters who had assembled. His father, a notary public, administered the oath of office in the family's parlor by the light of a kerosene lamp

at 2:47 a.m. on August 3, 1923; Coolidge then went back to bed.

Coolidge returned to Washington the next day, and was re-sworn by

Justice Adolph A. Hoehling, Jr. of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia, as there was some confusion over whether a state notary public had the authority to administer the presidential oath. (A somewhat similar situation had occurred with Chester A. Arthur.)

The

nation did not know what to make of its new President; Coolidge had not

stood out in the Harding administration and many had expected him to be

replaced on the ballot in 1924. He appointed C. Bascom Slemp, a Virginia Congressman and experienced federal politician to work jointly with Edward T. Clark, a Massachusetts Republican organizer whom he retained from his vice presidential staff, as Secretaries to the President (a position equivalent to the modern White House Chief of Staff).

Although many of Harding's cabinet appointees were scandal-tarred,

Coolidge announced that he would not demand any of their resignations,

believing that since the people had elected Harding, he should carry on

Harding's presidency, at least until the next election.

He addressed Congress when it reconvened on December 6, 1923, giving a speech that echoed many of Harding's themes, including immigration restriction and the need for the government to arbitrate the coal strikes then ongoing in Pennsylvania. The Washington Naval Treaty was proclaimed just one month into Coolidge's term, and was generally well received in the country. In May 1924, the World War I veterans' Bonus Bill was passed over his veto. Coolidge signed the Immigration Act later that year, though he appended a signing statement expressing his unhappiness with the bill's specific exclusion of Japanese immigrants. Just before the Republican Convention began, Coolidge signed into law the Revenue Act of 1924, which decreased personal income tax rates while increasing the estate tax, and creating a gift tax to reinforce the transfer tax system. The Democrats held their convention from

June 24 to July 9 in New York City. The convention soon deadlocked, and

after 103 ballots, the delegates finally agreed on a compromise

candidate, John W. Davis, with Charles W. Bryan nominated for Vice President. The Democrats' hopes were buoyed when Robert M. La Follette, Sr., a Republican Senator from Wisconsin, split from the party to form a new Progressive Party. Many believed that the split in the Republican party, like the one in 1912, would allow a Democrat to win the Presidency. Shortly

after the conventions Coolidge experienced a personal tragedy.

Coolidge's younger son, Calvin, Jr., developed a blister from playing tennis on the White House courts. The blister became infected, and within days Calvin, Jr. developed blood poisoning and

died. After that Coolidge became withdrawn. He later said that "when he

died, the power and glory of the Presidency went with him." In

spite of his sadness, Coolidge ran his conventional campaign; he never

maligned his opponents (or even mentioned them by name) and delivered

speeches on his theory of government, including several that were

broadcast over radio. It

was easily the most subdued campaign since 1896, partly because the

President was grieving for his son, but partly because Coolidge's style

was naturally non-confrontational. The

other candidates campaigned in a more modern fashion, but despite the

split in the Republican party, the results were very similar to those

of 1920. Coolidge and Dawes won every state outside the South except

for Wisconsin, La Follette's home state. Coolidge had a popular vote

majority of 2.5 million over his opponents' combined total. During Coolidge's presidency the United States experienced the period of rapid economic growth known as the "Roaring Twenties". He left the administration's industrial policy in the hands of his activist Secretary of Commerce, Herbert Hoover, who energetically used government auspices to promote business efficiency and develop airlines and radio. With

the exception of favoring increased tariffs, Coolidge disdained

regulation, and carried about this belief by appointing commissioners

to the Federal Trade Commission and the Interstate Commerce Commission who did little to restrict the activities of businesses under their jurisdiction. The regulatory state under Coolidge was, as one biographer described it, "thin to the point of invisibility." Coolidge's

economic policy has often been misquoted as "generally speaking, the

business of the American people is business".

Some have criticized Coolidge as an adherent of the laissez-faire ideology, which they claim led to the Great Depression. On the other hand, historian Robert Sobel offers some context based on Coolidge's sense of federalism: "As Governor of Massachusetts, Coolidge supported wages and hours legislation, opposed child labor, imposed economic controls during World War I,

favored safety measures in factories, and even worker representation on

corporate boards. Did he support these measures while president? No,

because in the 1920s, such matters were considered the responsibilities

of state and local governments."

Coolidge's taxation policy was that of his Secretary of the Treasury, Andrew Mellon: taxes should be lower and fewer people should have to pay them. Congress agreed, and the taxes were reduced in Coolidge's term. In addition to these tax cuts, Coolidge proposed reductions in federal expenditures and retiring some of the federal debt. Coolidge's ideas were shared by the Republicans in Congress, and in 1924 Congress passed the Revenue Act of 1924, which reduced income tax rates and eliminated all income taxation for some two million people. They reduced taxes again by passing the Revenue Acts of 1926 and 1928, all the while continuing to keep spending down so as to reduce the overall federal debt. By 1927, only the richest 2% of taxpayers paid any income tax. Although

federal spending remained flat during Coolidge's administration,

allowing one fourth of the federal debt to be retired, state and local

governments saw considerable growth, surpassing the federal budget in

1927. Perhaps

the most contentious issue of Coolidge's presidency was that of relief

for farmers. Some in Congress proposed a bill designed to fight falling

agricultural prices by allowing the federal government to purchase

crops to sell abroad at lowered prices. Agriculture Secretary Henry Wallace and

other administration officials favored the bill when it was introduced

in 1924, but rising prices convinced many in Congress that the bill was

unnecessary, and it was defeated just before the elections that year. In 1926, with farm prices falling once more, Senator Charles L. McNary and Representative Gilbert N. Haugen — both Republicans — proposed the McNary-Haugen Farm Relief Bill.

The bill proposed a federal farm board that would purchase surplus

production in high-yield years and hold it (when feasible) for later sale, or sell it abroad. Coolidge

opposed McNary-Haugen, declaring that agriculture must stand "on an

independent business basis," and said that "government control cannot

be divorced from political control." He favored instead Herbert Hoover's

proposal to modernize agriculture to create profits, instead of

manipulating prices. Secretary Mellon wrote a letter denouncing the

McNary-Haugen measure as unsound and likely to cause inflation, and it

was defeated. After

McNary-Haugen's defeat, Coolidge supported a less radical measure, the

Curtis-Crisp Act, which would have created a federal board to lend

money to farm co-operatives in times of surplus; the bill did not pass. In February 1927, Congress took up the McNary-Haugen bill again, this time narrowly passing it. Coolidge vetoed it. In

his veto message, he expressed the belief that the bill would do

nothing to help farmers, benefitting only exporters and expanding the

federal bureaucracy. Congress did not override the veto, but passed the bill again in May 1928 by an increased majority; again, Coolidge vetoed it. "Farmers never have made much money," said Coolidge, the Vermont farmer's son, "I do not believe we can do much about it."

Coolidge has often been criticized for his actions during the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, the worst natural disaster to hit the Gulf Coast until Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Although

he did eventually name Secretary Hoover to a commission in charge of

flood relief, Coolidge's lack of interest in federal flood control has

been criticized. Coolidge

did not believe that personally visiting the region after the floods

would accomplish anything, but would be seen only as political

grandstanding. He also did not want to incur the federal spending that

flood control would require; he believed property owners should bear

much of the cost. On the other hand, Congress wanted a bill that would place the federal government completely in charge of flood mitigation. When

Congress passed a compromise measure in 1928, Coolidge declined to take

credit for it and signed the bill in private on May 15. Coolidge spoke out in favor of the civil rights of African Americans and Catholics. He appointed no known members of Ku Klux Klan to office; indeed the Klan lost most of its influence during his term. In 1924, Coolidge responded to a letter that claimed the United States was a "white man's country": On June 2, 1924, Coolidge signed the Indian Citizenship Act, which granted full U.S. citizenship to all American Indians,

while permitting them to retain tribal land and cultural rights.

However, the act was not clear whether the federal government or the

tribal leaders retained tribal sovereignty. Coolidge repeatedly called for anti-lynching laws to be enacted, but most Congressional attempts to pass this legislation were filibustered by Southern Democrats. While he was not an isolationist, Coolidge was reluctant to enter into foreign alliances. Coolidge saw the landslide Republican victory of 1920 as a rejection of the Wilsonian idea that the United States should join the League of Nations. While

not completely opposed to the idea, Coolidge believed the League, as

then constituted, did not serve American interests, and he did not

advocate membership in it. He spoke in favor of the United States joining the Permanent Court of International Justice, provided that the nation would not be bound by advisory decisions. The Senate eventually approved joining the Court (with reservations) in 1926. The League of Nations accepted the reservations, but suggested some modifications of their own. The Senate failed to act; the United States never joined the World Court. Coolidge's best-known initiative was the Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1928, named for Coolidge's Secretary of State, Frank B. Kellogg, and French foreign minister Aristide Briand.

The treaty, ratified in 1929, committed signatories including the U.S.,

the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, and Japan to "renounce war,

as an instrument of national policy in their relations with one

another." The

treaty did not achieve its intended result – the outlawry of

war – but did provide the founding principle for international law

after World War II. Coolidge continued the previous administration's policy not to recognize the Soviet Union. He also continued the United States' support for the elected government of Mexico against the rebels there, lifting the arms embargo on that country. He sent his close friend Dwight Morrow to Mexico as the American ambassador. Coolidge represented the U.S. at the Pan American Conference in Havana, Cuba, making him the only sitting U.S. President to visit the country. The United States' occupation of Nicaragua and Haiti continued under his administration, but Coolidge withdrew American troops from the Dominican Republic in 1924. In the summer of 1927, Coolidge vacationed in the Black Hills of South Dakota, where he engaged in horseback riding and fly fishing and attended rodeos. He made Custer State Park his

"summer White House". News coverage of Coolidge's time in the Black

Hills soon increased tourism in the general region and promoted the

popularity of Wind Cave National Park. While

on vacation, Coolidge surprisingly issued his terse statement that he

would not seek a second full term as President in 1928: "I do not

choose to run for President in 1928." After allowing them to take that in, Coolidge elaborated. "If I take another

term, I will be in the White House till 1933 … Ten years in

Washington is longer than any other man has had it — too long!" In

his memoirs, Coolidge explained his decision not to run: "The

Presidential office takes a heavy toll of those who occupy it and those

who are dear to them. While we should not refuse to spend and be spent

in the service of our country, it is hazardous to attempt what we feel

is beyond our strength to accomplish." After

leaving office, he and Grace returned to Northampton, where he wrote

his memoirs. The Republicans retained the White House in 1928 in the

person of Coolidge's Secretary of Commerce, Herbert Hoover. Coolidge

had been reluctant to choose Hoover as his successor; on one occasion

he remarked that "for six years that man has given me unsolicited advice — all of it bad." Even so, Coolidge had no desire to split the party by publicly opposing the popular Commerce Secretary's nomination. The

delegates did consider nominating Vice President Charles Dawes to be

Hoover's running mate, but the convention selected Senator Charles Curtis instead. Despite

his reputation as a quiet and even reclusive politician, Coolidge made

use of the new medium of radio and made radio history several times

while President. He made himself available to reporters, giving 529

press conferences, meeting with reporters more regularly than any

President before or since. Coolidge's inauguration was

the first presidential inauguration broadcast on radio. On December 6,

1923, he was the first President whose address to Congress was

broadcast on radio. On February 22, 1924, he became the first President of the United States to deliver a political speech on radio. Coolidge signed the Radio Act of 1927, which assigned regulation of radio to the newly created Federal Radio Commission. On August 11, 1924, Lee DeForest filmed Coolidge on the White House lawn with DeForest's Phonofilm sound-on-film process, becoming the first President to appear in a sound film. The title of the DeForest film was President Coolidge, Taken on the White House Lawn. Coolidge was the only president to have his portrait on a coin during his lifetime, the Sesquicentennial of American Independence Half Dollar, minted in 1926. After his death he also appeared on a postage stamp. Since it was part of a series depicting all deceased presidents, his was the last and highest denomination issued.

Coolidge appointed one Justice to the Supreme Court of the United States, Harlan Fiske Stone in 1925. Stone was Coolidge's fellow Amherst alumnus and was serving as dean of Columbia Law School when Coolidge appointed him to be Attorney General in 1924. He nominated Stone to the Supreme Court in 1925, and the Senate confirmed the nomination. Stone was later appointed Chief Justice by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Along with his Supreme Court appointment, Coolidge successfully nominated 17 judges to the United States Courts of Appeals, and 61 judges to the United States district courts. He appointed judges to various specialty courts as well, including Genevieve R. Cline, who became the first woman named to the Federal judiciary when Coolidge placed her on the United States Customs Court in 1928. Coolidge also signed the Judiciary Act of 1925 into law, allowing the Supreme Court more discretion over its workload. After his presidency, Coolidge retired to his beloved Northampton home , "The Beeches," where he became a local fixture. He kept a Hacker runabout

boat on the Connecticut river and was often observed on the water by

local boating enthusiasts. During this period he also served as

chairman of the non-partisan Railroad Commission, as honorary president

of the American Foundation for the Blind, as a director of New York Life Insurance Company, as president of the American Antiquarian Society, and as a trustee of Amherst College. Coolidge received an honorary Doctor of Laws from Bates College in Lewiston, Maine. Coolidge published his autobiography in 1929 and wrote a syndicated newspaper column, "Calvin Coolidge Says," from 1930 – 1931. Faced

with looming defeat in 1932, some Republicans spoke of rejecting

Herbert Hoover as their party's nominee, and instead drafting Coolidge

to run, but the former President made it clear that he was not

interested in running again, and that he would publicly repudiate any

effort to draft him, should it come about. Hoover was renominated, and Coolidge made several radio addresses in support of him. He died suddenly of a heart attack at "The Beeches," at 12:45 p.m., January 5, 1933. Shortly before his death, Coolidge confided to an old friend: "I feel I am no longer fit in these times." Coolidge is buried beneath a simple headstone in Notch Cemetery, Plymouth Notch, Vermont, where the family home is maintained as one of the original buildings on the site, all of which comprise the Calvin Coolidge Homestead District. The State of Vermont dedicated a new visitors' center nearby to mark Coolidge's 100th birthday on July 4, 1972. Calvin Coolidge's "Brave Little State of Vermont speech" is memorialized in the Hall of Inscriptions at the Vermont State House in Montpelier, Vermont.

The Republican Convention was held from June 10–12, 1924 in Cleveland, Ohio; President Coolidge was nominated on the first ballot. The convention nominated Frank Lowden of Illinois for Vice President on the second ballot, but he declined by telegram. Former Brigadier General Charles G. Dawes, who would win the Nobel Peace Prize in 1925, was nominated on the third ballot; he accepted.

“ ....I

was amazed to receive such a letter. During the war 500,000 colored men

and boys were called up under the draft, not one of whom sought to

evade it. [As president, I am] one who feels a responsibility for

living up to the traditions and maintaining the principles of the

Republican Party. Our Constitution guarantees equal rights to all our

citizens, without discrimination on account of race or color. I have

taken my oath to support that Constitution.... ”