<Back to Index>

- Meteorologist and 2nd Governor of New Zealand Robert FitzRoy, 1805

- Author Jean Maurice Eugène Clément Cocteau, 1889

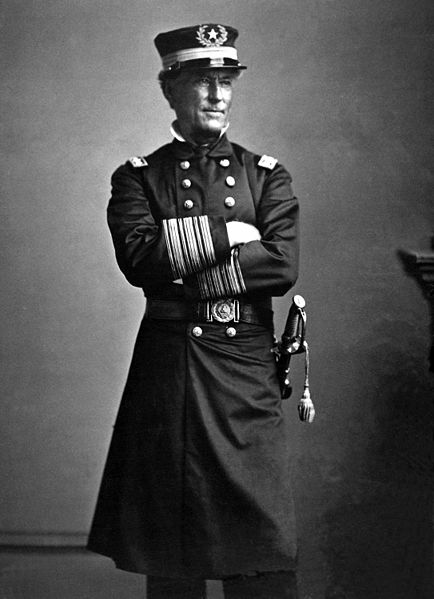

- Admiral of the United States Navy David Glasgow Farragut, 1801

PAGE SPONSOR

David Glasgow Farragut (July 5, 1801 – August 14, 1870) was a flag officer of the United States Navy during the American Civil War. He was the first rear admiral, vice admiral, and full admiral of the Navy. He is remembered in popular culture for his order at the Battle of Mobile Bay, usually paraphrased: "Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!" by U.S. Navy tradition.

Farragut was born to Jorge Farragut and Elizabeth Shine Farragut at Lowe's Ferry on the Holston (now Tennessee) River a few miles southeast of Campbell's Station, near Knoxville, Tennessee, where his family lived. His father operated the ferry and was a cavalry officer in the Tennessee militia. Jorge Farragut, a Spanish merchant captain from Minorca, son of Antoni Farragut and Joana Mesquida, had previously joined the American Revolutionary cause after arriving in America in 1768. Jorge Farragut married Elizabeth Shine (b.1765 - d.1808) from North Carolina and moved west to Tennessee after serving in the American Revolution. David's birth name was James, but it was changed in 1812, following his adoption by future naval Captain David Porter in 1808 (which made him the foster brother of future Civil War Admiral David Dixon Porter and Commodore William D. Porter).

Through the influence of Cmdr. David D. Porter, who had adopted him, Farragut was commissioned a midshipman in the United States Navy on Dec 10, 1810, at the age of nine, and served under Porter during the War of 1812. A prize master by the age of 12 Farragut was promoted to lieutenant in 1822, commander in 1844 and captain in 1855.

Farragut was wounded and captured during the cruise of the Essex by HMS Phoebe in Valparaiso Bay, Chile, on March 28, 1814. He had a son named Loyall Farragut by his second wife, Virginia Loyall.

In 1853, Secretary of the Navy James C. Dobbin selected Commander David G. Farragut to create Mare Island Naval Shipyard.

In August 1854, Farragut was called to Washington from his post as

Assistant Inspector of Ordinance at Norfolk, Virginia. President

Franklin Pierce congratulated Farragut on his naval career and the task

he was to undertake. September 16, 1854, Commander Farragut commissioned the Mare Island Naval Yard at Vallejo, California. Mare

Island became the port for ship repair on the West Coast. Captain

Farragut left command of Mare Island, July 16, 1858. Farragut returned

to a hero’s welcome at Mare Island, August 11, 1859. Though living in Norfolk, Virginia, prior to the Civil War, he made it clear to all who knew him that he regarded secession as treason. Just before the war's outbreak he moved with his Southern born wife to Hastings-on-Hudson, a small town just outside New York City.

He offered his services to the Union but was initially given just a

seat on the Naval Retirement Board. Offered a command for a special

assignment by his foster brother David Dixon Porter,

he initially hesitated upon learning the target might be Norfolk, as he

had friends and relatives living there; he eventually accepted and was

relieved to learn the target was New Orleans. Doubts were raised by the

Navy about Farragut's loyalty to the Union because of his southern

birth as well as that of Mrs. Farragut. Porter, however, argued on

Farragut's behalf, and Farragut was accepted for the major role of freeing

New Orleans from Confederate control. In command of the West Gulf Blockading Squadron, with his flag on the USS Hartford, in April 1862, after a heavy bombardment, he ran past Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip and the Chalmette, Louisiana, batteries to take the city and port of New Orleans, Louisiana on April 29, a decisive event in the war. Congress honored him by creating for him the rank of rear admiral on

July 16, 1862, a rank never before used in the U.S. Navy. Before this

time, the American Navy had resisted the rank of admiral, preferring

the term "flag officer", to separate it from the traditions of the

European navies. Later that year he passed the batteries defending Vicksburg, Mississippi. Farragut had no real success at Vicksburg; one makeshift Confederate ironclad forced his flotilla of 38 ships to withdraw in July 1862. While he was a very aggressive commander, Farragut was not always cooperative. At the Siege of Port Hudson the plan was that Farragut's flotilla would pass by the guns of the Confederate stronghold with the help of a diversionary land attack by the Army of the Gulf, commanded by General Nathaniel Banks,

to commence at 8:00 am on March 15, 1863. Farragut unilaterally decided

to move the timetable up to 9:00 pm on March 14, and initiated his run

past the guns before Union ground forces were in position. By doing so,

the uncoordinated attack allowed the Confederates to concentrate on

Farragut's flotilla and inflict heavy damage on his warships.

Farragut's battle group was forced to retreat with only two ships able

to pass the

heavy cannon of the Confederate bastion. After surviving the gauntlet,

Farragut played no further part in the battle for Port Hudson, and General Banks was left to continue the siege without advantage of naval support. The Union Army made

two major attacks on the fort, and both were repulsed with heavy

losses. Farragut's flotilla was splintered, yet was able to blockade

the mouth of the Red River with

the two remaining warships; he could not efficiently patrol the section

of the Mississippi between Port Hudson and Vicksburg. Farragut's

decision thus proved costly to the Union Navy and the Union Army, which suffered its highest casualty rate of the Civil War at Port Hudson. Vicksburg surrendered on July 4, 1863, leaving Port Hudson as the last remaining Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River.

General Banks accepted the surrender of the Confederate garrison at

Port Hudson on July 9, 1863, ending the longest siege in US military history. Control of the Mississippi River was

the centerpiece of Union strategy to win the war, and with the

surrender of Port Hudson the Confederacy was now severed in two. On August 5, 1864, Farragut won a great victory in the Battle of Mobile Bay. Mobile was then the Confederacy's last major port open on the Gulf of Mexico. The bay was heavily mined (tethered naval mines were known as torpedoes at the time). Farragut ordered his fleet to charge the bay. When the monitor USS Tecumseh struck

a mine and sank, the others began to pull back. Farragut could see the

ships pulling back from his high perch, lashed to the rigging of his

flagship, the USS Hartford. "What's the trouble?" was shouted through a trumpet from the flagship to the USS Brooklyn. "Torpedoes!" was shouted back in reply. "Damn the torpedoes!" said Farragut, "Four bells. Captain Drayton, go ahead! Jouett, full speed!" The bulk of the fleet succeeded in entering the bay. Farragut then triumphed over the opposition of heavy batteries in Fort Morgan and Fort Gaines to defeat the squadron of Admiral Franklin Buchanan. Farragut was promoted to vice admiral on December 21, 1864, and to admiral on July 25, 1866, after the war. His last active service was in command of the European Squadron from 1867 to 1868, with the screw frigate USS Franklin as his flagship. Farragut remained on active duty for life, an honor accorded to only six other US naval officers.

Farragut died at the age of sixty-nine in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, from a stroke while on vacation in the late summer of 1870. He is interred at Woodlawn Cemetery, in the Bronx borough of New York.