<Back to Index>

- Mathematician William Feller, 1906

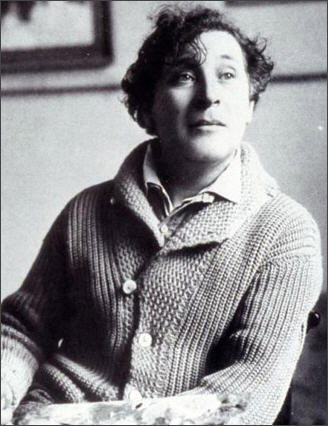

- Painter Marc Chagall, 1887

- Emperor of Japan Sutoku, 1119

PAGE SPONSOR

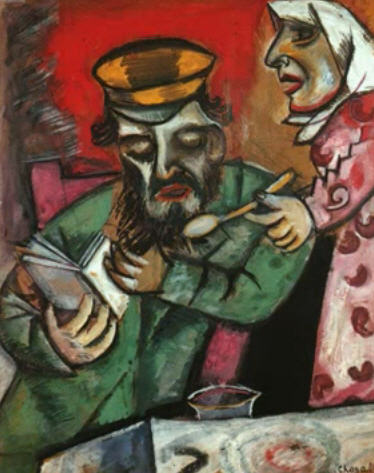

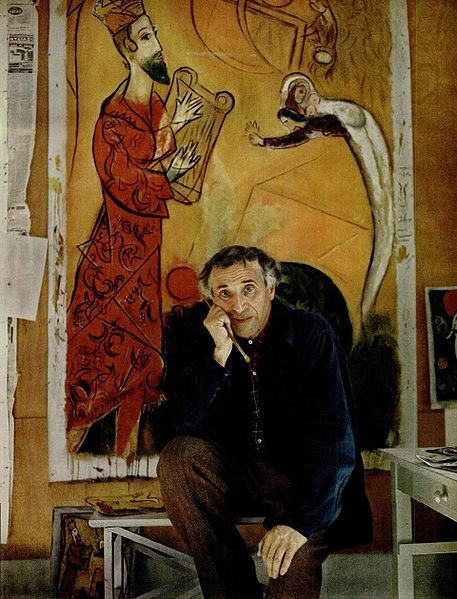

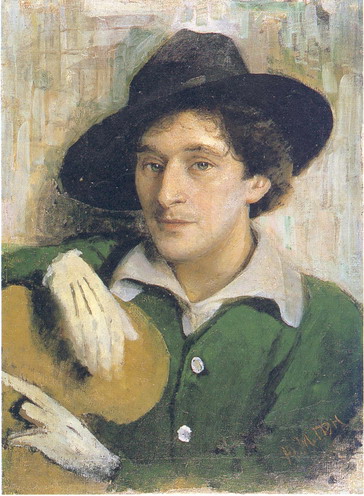

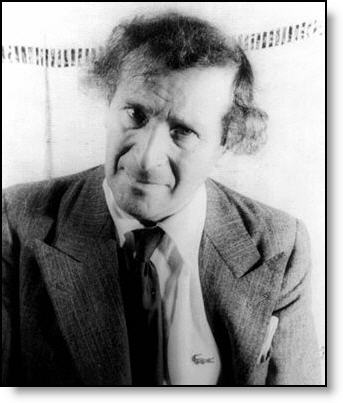

Marc Chagall (Yiddish: מאַרק שאַגאַל; Russian: Марк Заха́рович Шага́л; 7 July 1887 – 28 March 1985), was a Russian–French artist, associated with several key art movements and was one of the most successful artists of the twentieth century. He created a unique career in virtually every artistic medium, including paintings, book illustrations, stained glass, stage sets, ceramics, tapestries and fine art prints. Chagall's haunting, exuberant, and poetic images have enjoyed universal appeal, with art critic Robert Hughes referring to him as "the quintessential Jewish artist of the twentieth century."

As a pioneer of modernism and one of the greatest figurative artists of

the twentieth century, Marc Chagall achieved fame and fortune, and over

the course of a long career created some of the best-known paintings of

our time. According to art historian Michael J. Lewis, Chagall was

considered to be "the last survivor of the first generation of European

modernists." For decades he "had also been respected as the world's

preeminent Jewish artist." Using the medium of stained glass, he produced windows for the cathedrals of Reims and Metz, windows for the United Nations, and the Jerusalem Windows in Israel. He also did large-scale paintings, including the ceiling for the Paris Opéra. His most vital work was made on the eve of World War I, when he traveled between St. Petersburg, Paris, and Berlin. During this period he created his own mixture and style of modern art based on his visions of Eastern European Jewish folk culture. He spent his wartime years in Russia, becoming one the

country's most distinguished artists and a member of the modernist avante-garde, founding the Vitebsk Arts College before leaving again for Paris in 1922. He

was known to have two basic reputations, writes Lewis – as a pioneer of

modernism, and as a major Jewish artist. He experienced modernism's

golden age in Paris, where "he synthesized the art forms of Cubism, Symbolism, and Fauvism, and the influence of Fauvism gave rise to Surrealism." Yet throughout these phases of his style "he remained most emphatically

a Jewish artist, whose work was one long dreamy reverie of life in his

native village of Vitebsk." "When Matisse dies", Pablo Picasso remarked in the 1950s, "Chagall will be the only painter left who understands what colour really is." Marc Chagall, born Moishe Shagal, was born in Liozna, near the city of Vitebsk (Belarus, then part of the Russian Empire) in 1887. At the time of his birth, Vitebsk's population was around 66,000, with half the population being Jewish. A picturesque city of churches and synagogues, it was called "Russian Toledo", after the former cultural center of the Spanish Empire.

As the city was mostly built of wood, little of it survived three years

of Nazi occupation and destruction during World War II. Chagall was the eldest of nine children in a Jewish Levitic family

led by his father Khatskl (Zakhar) Shagal, employed by a herring

merchant, and his mother, Feige-Ite, who sold groceries from their

home. His father worked hard, carrying heavy barrels but earning only

20 roubles a month. Chagall would later include fish motifs "out of

respect for his father", writes Chagall biographer, Jacob Baal-Teshuva.

Chagall wrote of these early years: During the previous decades, the Jewish population of the town survived numerous government organized attacks (pogroms),

prejudice, segregation, and discrimination. As a result, they created

their own schools, synagogues, hospitals, a cemetery, and other

community institutions. One of their key sources of income was from the

manufacture of clothing that was sold throughout Russia. They also made

furniture and various agricultural tools. Art

historian and curator Susan Tumarkin Goodman writes that for religious

and economic reasons from the late 1700s to the First World War, Russia

confined Jews to living within the Pale of Settlement, which included sections of modern Ukraine, Belarus, Poland, and the Baltic States. This caused the natural creation of Jewish market villages (shtetls) throughout today's Eastern Europe, with their own markets, culture, and religious observances. Most of what is known about Chagall's early life has come from his autobiograhy, My Life.

In it, he described the major influence that the culture of Hasidic

Judaism had on his life as an artist. Vitebsk itself had been a center

of that culture dating from the 1730s with its teachings derived from

the Kabbalah. Goodman describes the links and sources of his art to his early home: A

turning point in his artistic life came when he first noticed a fellow

student drawing. Baal-Teshuva writes that for the young Chagall,

watching someone draw "was like a vision, a revelation in black and

white." Chagall would later say how there was no art of any kind in his

family's home and the concept was totally foreign to him. When Chagall

asked the schoolmate how he learned to draw, his friend replied, "Go

and find a book in the library, idiot, choose any picture you like, and

just copy it." He soon began copying images from books and found the

experience so rewarding he then decided he wanted to become an artist.

He

eventually confided to his mother, "I want to be a painter", although

she could not understand his sudden interest in art or why he would

choose a vocation that "seemed so impractical", writes Goodman. The

young Chagall explained, "There's a place in town; if I'm admitted and

if I complete the course, I'll come out a regular artist. I'd be so

happy!" It was 1906, and he had noticed the studio of Yehuda (Yuri) Pen, a realist artist who also ran a small drawing school in Vitebsk, which included future luminaries as El Lissitzky and Ossip Zadkine.

Due to Chagall's youth and lack of income, Pen offered to teach him

free of charge. However, after a few months at the school, Chagall

realized that academic portrait painting did not suit his desires. Goodman

notes that during this period in Russia, Jews had two basic

alternatives for joining the art world: One was to "hide or deny one's

Jewish roots", by moving away from any public expressions of

Jewishness, in order to avoid the discrimination endemic in Russian

society. The other alternative — the one that Chagall chose — was "to

cherish and publicly express one's Jewish roots" by integrating them

into his art. For Chagall, this was also his means of "self-assertion

and an expression of principle." Chagall

biographer Franz Meyer, explains that with the connections between his

art and early life "the hassidic spirit is still the basis and source

of nourishment for his art." Lewis

adds, "As cosmopolitan an artist as he would later become, his

storehouse of visual imagery would never expand beyond the landscape of

his childhood, with its snowy streets, wooden houses, and ubiquitous

fiddlers. . . . [with] scenes of childhood so indelibly in one's mind

and to invest them with an emotional charge so intense that it could

only be discharged obliquely through an obsessive repetition of the

same cryptic symbols and ideograms . . . " Years

later, at the age of 57 while living in America, Chagall confirmed this

when he published an open letter entitled, "To My City Vitebsk": In 1906, he moved to St. Petersburg which

was then the capital of Russia and the center of the country's artistic

life with its famous art schools. Since Jews were not permitted into

the city without an internal passport, he managed to get a temporary

passport from a friend. He enrolled in a prestigious art school and

studied there for two years. By 1907 he had begun painting naturalistic self-portraits and landscapes. During 1908 to 1910, Chagall studied under Léon Bakst at

the Zvantseva School of Drawing and Painting. While in St. Petersburg

he discovered experimental theater and the work of such artists as Paul Gauguin. Bakst,

also Jewish, was a designer of decorative art and was famous as a

draftsman designer of stage sets and costumes for the 'Ballets Russes,'

and helped Chagall by acting as a role model for Jewish success. Bakst

moved to Paris a year later. Art historian Raymond Cogniat writes that

after living and studying art on his own for four years, "Chagall

entered into the mainstream of contemporary art. . . . His

apprenticeship over, Russia had played a memorable initial role in his

life. Chagall stayed in St. Petersburg until 1910, often visiting Vitebsk where he met and fell in love with Bella Rosenfeld. In My Life Chagall described his first meeting her: "Her silence is mine, her eyes mine.

It is as if she knows everything about my childhood, my present, my

future, as if she can see right through me."

In

1910 Chagall moved to Paris to develop his own artistic style. Art

historian and curator James Sweeney notes that when Chagall first

arrived in Paris, Cubism was the dominant art form and French art was

still dominated by the "materialistic outlook of the 19th century." But

Chagall arrived from Russia with "a ripe color gift, a fresh, unashamed

response to sentiment, a feeling for simple poetry and a sense of

humor", he adds. These notions were foreign to Paris at that time, and

as a result his first recognition came not from other painters but from

poets such as Blaise Cendrars and Guillaume Apollinaire. Art

historian Jean Leymarie observes that Chagall began thinking of art as

"emerging from the internal being outward, from the seen object to the

psychic outpouring", which was the reverse of the Cubist way of

creating. He therefore developed friendships with Guillaume Apollinaire and other avant-garde luminaries such as Robert Delaunay and Fernand Léger. Baal-Teshuva writes that "Chagall's dream of Paris, the city of light and above all, of freedom, had come true." His

first days were a hardship for the 23 year old Chagall, who found

himself alone in the big city and unable to speak French. Some days he

"felt like fleeing back to Russia, as he daydreamed while he painted,

about the riches of Russian folklore, his Hasidic experiences, his family, and especially Bella.

In Paris he enrolled at La Palette, an art academy where the painters André Dunoyer de Segonzac and Henri Le Fauconnier taught, and also found work at another academy. He would spend his free hours visiting galleries and salons, especially the Louvre, where he would study the works of Rembrandt, the Le Nain brothers, Chardin, van Gogh, Renoir, Pissarro, Matisse, Gauguin, Courbet, Millet, Manet, Monet, Delacroix, and others. It was in Paris that he learned the technique of gouache, which he used to paint Russian scenes. He also visited Montmartre and the Latin Quarter, "and was happy just breathing Parisian air." Baal-Teshuva describes this new phase in Chagall's artistic development: Another

completely new world that opened up for him was the kaleidoscope of

colours and forms in the works of French artists. Chagall

enthusiastically reviewed their many different tendencies, having to

rethink his position as an artist and decide what creative avenue he

wanted to pursue. During

his time in Paris Chagall was constantly reminded of his home in

Russia, as Paris was also home to many Russian painters, writers,

poets, composers, dancers, and other émigre′s. However, "night

after night he painted until dawn", only then going to bed for a few

hours, and resisted the many temptations of the big city at night. "My homeland exists only in my soul", he once said. He

continued painting Jewish motifs and subjects from his memories of

Vitebsk, although he included Parisian scenes – the Eiffel Tower in

particular, along with portraits. Many of his works were updated

versions of paintings he had made in Russia, transposed into Fauvist or Cubist keys. Chagall

developed a whole repertoire of quirky motifs: the ghostly figure

floating in the sky, . . . the gigantic fiddler dancing on miniature

dollhouses, the livestock and transparent wombs and, within them, tiny

offspring sleeping upside down. The

majority of his scenes of life in Vitebsk were painted while living in

Paris, and "in a sense they were dreams", notes Lewis. Their "undertone

of yearning and loss", with a detached and abstract appearance, caused

Apollinaire to be "struck by this quality", calling them "surnaturel!"

His "animal/human hybrids and airborne phantoms" would later become a

formative influence on Surrealism. Chagall, however, did not want his work to be associated with any school or

movement and considered his own personal language of symbols to be

meaningful to himself. But Sweeney notes that others often still

associate his work with "illogical and fantastic painting", especially

when he uses "curious representational juxtapositions." Sweeney

writes that "This is Chagall's contribution to contemporary art: the

reawakening of a poetry of representation, avoiding factual

illustration on the one hand, and non-figurative abstractions on the

other." André Breton said that "with him alone, the metaphor made its triumphant return to modern painting."

Because

he missed not being with his fiancée, Bella, who was still in

Vitebsk, "He thought about her day and night", writes Baal-Teshuva, and

was afraid of losing her. He therefore decided to accept an invitation

from a noted art dealer in Berlin to exhibit his work, his intention

being to continue on to Russia, marry Bella, and then return with her

to Paris. Chagall took 40 canvases and 160 gouaches, watercolors and

drawings to be exhibited. The exhibit, held at Herwarth Walden's Sturm gallery was a huge success, "The German critics positively sang his praises." After

the exhibit, he continued on to Vitebsk, where he planned to stay only

long enough to marry Bella. However, after a few weeks, the First World

War broke out, closing the Russian border for an indefinite period. A

year later he married Bella Rosenfeld and had their first child, Ida.

Before the marriage, Chagall had difficulty convincing Bella's parents

that he would be a suitable husband for their daughter. They were

worried about her marrying a painter from a poor family and wondered

how he would support her. Becoming a successful artist now became a

goal and inspiration. Hence, despite the ongoing war, Chagall's spirits

remained high, mostly due to his marriage. According to Lewis, "[T]he

euphoric paintings of this time, which show the young couple floating

balloon-like over Vitebsk — its wooden buildings faceted in the Delaunay

manner — are the most lighthearted of his career." His wedding pictures were also a subject he would return to in later years as he thought about this period of his life.

The October Revolution of 1917 was

a dangerous time for Chagall although it also offered opportunity. By

then he was one of the Soviet Union's most distinguished artists and a

member of the modernist avant-garde, which enjoyed special privileges and prestige as the "aesthetic arm of the revolution." He

was offered a notable position as a commissar of visual arts for the

country, but preferred something with a lower profile, and instead took

a position as commissar of arts for Vitebsk. This resulted in his

founding the Vitebsk Arts College which, adds Lewis, became the "most

distinguished school of art in the Soviet Union." It obtained for its faculty some of the most important artists in the country, such as El Lissitzky and Kazimir Malevich. He also added his first teacher, Yehuda Pen.

Chagall tried to create an atmosphere of a collective or independently

minded artists, each with their own unique style. However, this would

soon prove to be difficult as a few of the key faculty members

preferred a Suprematist art

of squares and circles, and looked down on Chagall's attempt at

creating "bourgeois individualism" in their teachings. Chagall then

resigned as commissar and moved to Moscow. In

1915 Chagall began exhibiting his work in Moscow, first exhibiting his

works at a well-known salon and in 1916 exhibiting pictures in St.

Petersburg. He again showed his art at a Moscow exhibition of

avant-garde artists. This constant exposure caused his name to spread

and a number of wealthy collectors began buying his art. He also began

illustrating a number of Yiddish books with ink drawings. Chagall had

turned 30 and had begun to make a name for himself. In

Moscow he was offered a position as stage designer for the newly formed

State Jewish Chamber Theater. It was set to open in early 1921 with a

number of plays by Sholem Aleichem.

For its opening he created a number of large background murals using

techniques he learned from Bakst, his early teacher. One of the key

murals was 9 feet tall by 24 feet long and included images of various

lively subjects such as dancers, fiddlers, acrobats, and farm animals.

One critic at the time called it "Hebrew jazz in paint." Chagall

created it as a "storehouse of symbols and devices", notes Lewis. The

murals "constituted a landmark" in the history of the theatre, and were

forerunners of his later large-scale works, including murals for the New York Metropolitan Opera and the Paris Opera. Life

quickly became a hardship for Russians as famine spread after the war

ended in 1918. The Chagalls found it necessary to move to a smaller,

less expensive, town near Moscow, although he now had to commute to

Moscow daily using crowded trains. In Moscow he found a job teaching

art to war orphans. After spending the years between 1921 and 1922

living in primitive conditions, he decided to move back to France so

that his art could grow in an atmosphere of greater freedom. Numerous

other artists, writers, and musicians were also planning to move to the

West. He applied for an exit visa and while waiting for its uncertain

approval, wrote his autobiography, My Life. In

1923 Chagall left Moscow to return to France. On his way he stopped in

Berlin to recover the many pictures he had left there on exhibit ten

years earlier, before the war began, but was unable to find or recover

any of them. Nonetheless, after returning to Paris he again

"rediscovered the free expansion and fulfilment which were so essential

to him", writes Lewis. With all his early works now lost, he began

trying to paint from his memories of his earliest years in Vitebsk with

sketches and oil paintings. He formed a business relationship with French art dealer Ambroise Vollard. This inspired him to begin creating etchings for a series of illustrated books, including Gogol's Dead Souls, the Bible, and the Fables of La Fontaine. These illustrations would eventually come to represent his finest printmaking efforts. By

1926 he had his first exhibition in the United States at the Reinhardt

gallery of New York which included about 100 works, although he did not

travel to the opening. He instead stayed in France, "painting

ceaselessly", notes Baal-Teshuva. It

was not until 1927 that Chagall made his name in the French art world,

when art critic and historian Maurice Raynal awarded him a place in his

book Modern French Painters. However, Raynal was still at a loss to accurately describe Chagall to his readers: During this period he traveled throughout France and fell in love with Côte d'Azur, where he enjoyed the landscapes, colorful vegetation, the blue Mediterranean,

and the mild weather. He made repeated trips to the countryside, always

taking his sketchbook. His wife Bella had a special role in his life.

Wullschlager notes that "she was the living connection to Russia that

allowed him to evolve as an artist in exile, in contrast to most

Russian artistic emigrés, whose work withered once they left

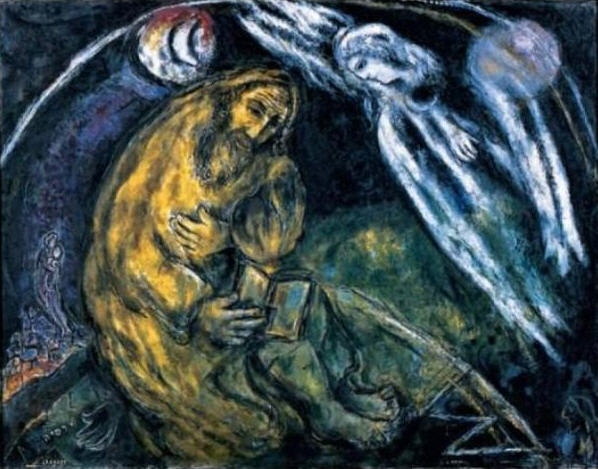

their homeland." He also visited nearby countries and later wrote about the impressions some of those travels left on him: After returning to Paris from one of his trips, Vollard commissioned him to illustrate the Old Testament version

of the Bible. Although he could have completed the project in France,

he used the assignment as an excuse to travel to Palestine to

experience for himself the Holy Land.

He arrived there in February 1931 and ended up staying for two months.

Chagall felt at home in Palestine where many spoke Yiddish and Russian.

According to Baal-Teshuva, "he was impressed by the pioneering spirit

of the people in the kibbutzim and deeply moved by the Wailing Wall and

the other holy places." Chagall

later told a friend that Palestine gave him "the most vivid impression

he had ever received." Wullschlager notes, however, that whereas

Delacroix and Matisse had found inspiration in the exoticism of North

Africa, he as a Jew in Palestine had different perspective. "What he

was really searching for there was not external stimulus but an inner

authorization from the land of his ancestors, to plunge into his work

on the Bible illustrations." Chagall

stated that "In the East I found the Bible and part of my own being."

As

a result, he immersed himself in "the history of the Jews, their

trials, prophecies, and disasters", notes Wullschlager. She adds that

taking on the assignment was an "extraordinary risk" for Chagall, as he

had finally made his name in the art world as a leading contemporary

painter, but would now pull away from modernist themes and delve into

"an ancient past." Between 1931 and 1934 he worked "obsessively" on "The Bible", even going to Amsterdam in order to carefully study the biblical paintings by Rembrandt and El Greco,

to see the extremes in religious painting. He walked the streets of the

city's Jewish quarter to again feel the earlier atmosphere. He told

Franz Meyer: Chagall saw the Old Testament as

a "human story, . . . not with the creation of the cosmos but with the

creation of man, and his figures of angels are rhymed or combined with

human ones", writes Wullschlager. She points out that in one of his

early Bible images, "Abraham and the Three Angels", the angels sit and

chat over a glass of wine "as if they have just dropped by for dinner." He

returned to France and by the following year had completed 32 out of

the total of 105 plates. By 1939, at the outbreak of World War II, he

had finished 66. However, Vollard died that same year. When the series

was completed in 1956, it was published by Edition Tériade.

Baal-Teshuva writes that "the illustrations were stunning and met with

great acclaim." Once again Chagall had shown himself to be one of the

20th century's most important graphic artists." Leymarie has described these drawings by Chagall as "monumental": Not long after Chagall began his work on the Bible, Adolf Hitler came to power in Berlin. Anti-Semitic laws were being introduced and the first concentration camp at Dachau had opened. Wullschlager describes the early affects on the art world: Beginning in 1937 around twenty thousand works from German museums were confiscated as "degenerate" by a committee headed by Joseph Goebbels." Although

the German press had once "swooned over him", the new German leadership

now made a mockery of Chagall's art, describing them as "green, purple,

and red Jews shooting out of the earth, fiddling on violins, flying

through the air . . . representing [an] assault on Western

civilization.". After Germany invaded and occupied France, the Chagalls naively remained in Vichy France, unaware that French Jews, with the help of the Vichy government,

were being collected and sent to German concentration camps, from which

nearly all would never return. The Vichy collaborationist government,

led by Marshal Philippe Pétain,

immediately upon assuming power set up a commission to "redefine French

citizenship" with the aim of stripping "undesirables", including

naturalized citizens, of their French nationality. Chagall had been so

involved in his art, that it was not until October 1940, after the

Vichy government, at the behest of the Nazi occupying forces, began

passing anti-Semitic laws, that he began to understand the significance

what was happening around him. Hearing that Jews were being removed

from public and academic positions, the Chagalls finally "woke up to

the danger they faced." But Wullschlager notes that "by then they were

trapped." Their

only refuge could be America, but "they could not afford the passage to

New York" or the large bond that each immigrant had to provide upon

entry to ensure that they would not become a financial burden to the

country. According

to Wullschlager, "[T]he speed with which France collapsed astonished

everyone: the French army, with British support, capitulated even more

quickly than Poland had done" a year earlier, even though Poland had

been attacked by both Germany and Russia. "Shock waves crossed the

Atlantic... as Paris had until then been equated with civilization

throughout the non-Nazi world." Yet the attachment of the Chagalls to France "blinded them to the urgency of the situation." Nor were they alone in their slow reaction to the coming Holocaust,

to be aided by France's collaboration, as many other well-known Russian

and Jewish artists eventually sought to escape: these included Chaim Soutine, Max Ernst, Max Beckmann, Ludwig Fulda, author Victor Serge and prize winning author Vladimir Nabokov, who although not Jewish himself, took a "passionate interest" in Jews and Israel. Russian author Victor Serge described many of the people temporarily living in Marseilles who were waiting to emigrate to America: After prodding by their daughter Ida, who "perceived the need to act fast," and with help from Alfred Barr of the New York Museum of Modern Art,

Chagall was saved by having his name added to the list of prominent

artists, whose lives were at risk, that the United States should try to

extricate. He left France in May 1941, "when it was almost too late",

adds Lewis. Picasso and Matisse were

also among artists invited to come to America but they decided to

remain in France. Chagall and Bella arrived in New York on June 23,

1941, which was the next day after Germany invaded Russia. Even before arriving in America in 1941, Chagall was awarded the Carnegie Prize in

1939. After being in America he discovered that he had already achieved

"international stature", writes Cogniat. He felt ill-suited in this new

role in a foreign country, however, one whose language he could not yet

speak. He became a public figure mostly against his will, feeling lost

in the strange surroundings.

What

compounded his discomfort in America was his knowing that he left

France under Nazi occupation and that the fate of millions of other

Jews was at risk. After a while he began to settle down in New York

which was full of writers, painters, and composers who, like himself,

had fled from Europe during the Nazi invasions. He spent time visiting

galleries and museums, and befriended other painters including Piet Mondrian and André Breton. Baal-Teshuva writes that Chagall "loved" going to the sections of New York where Jews lived, especially the Lower East Side.

There he felt at home, enjoying the Jewish foods and being able to read

the Yiddish press, which became his main source of information since he

did not yet speak English. Contemporary

artists did not yet understand or even like Chagall's art. According to

Baal-Teshuva, "they had little in common with a folkloristic storyteller of Russo-Jewish extraction with a propensity for

mysticism." The Paris School, which was referred to as 'Parisian Surrealism,' meant little to them. Those attitudes would begin to change, however, when Pierre Matisse, the son of recognized French artist Henri Matisse,

became his representative and held Chagall exhibitions in New York and

Chicago in 1941. One of the earliest exhibitions included 21 of his

masterpieces from 1910 to 1941. Art critic Henry McBride wrote about this exhibit for the New York Sun: He was offered a commission by choreographer Leonid Massine, of the New York Ballet Theatre to design the sets and costumes for his new ballet, Aleko. This ballet would stage the words of Pushkin's verse narrative The Gypsies with the music of Rachmaninoff.

While Chagall had done stage settings before while in Russia, this was

his first ballet, and it would give him the opportunity to visit Mexico. While there he quickly began to appreciate the "primitive ways and

colorful art of the Mexicans," notes Cogniat. He found "something very

closely related to his own nature", and did all the color detail for

the sets while there. Eventually,

he created four large backdrops and had Mexican seamstresses sew the

ballet costumes. When the ballet premiered on September 8, 1942 it was

considered a "remarkable success." In the audience were other famous mural painters who came to see Chagall's work, including Diego Rivera and José Orozco.

According to Baal-Teshuva, when the final bar of music ended, "there

was a tumultuous applause and 19 curtain calls, with Chagall himself

being called back onto the stage again and again." The ballet also

opened in New York City four weeks later at the Metropolitan Opera and the response was repeated, "again Chagall was the hero of the evening." Art critic Edwin Denby wrote of the opening for the New York Herald Tribune that Chagall's work: After

Chagall returned to New York in 1943, however, current events began to

take on more importance for him, and this was reflected in his art,

where he painted subjects including the Crucifixion and scenes of war. He heard that the Germans had destroyed the town where he was raised, Vitebsk, and became greatly distressed. He heard about the concentration camps and learned more about the occupation of France. By 1944, months before the Allies attempted to liberate France,

he was coming to grips with the reality and significance of the war in

Europe and on its Jewish populations. During a speech in February 1944,

he described some of his feelings: In the same speech he credited his homeland of Russia with doing the most to save the Jews: On

September 2, 1944, Bella died suddenly due to a virus infection, which

was not treated due to the wartime shortage of medicine. As a result,

he stopped all work for many months, and when he did resume painting

his first pictures were concerned with preserving Bella's memory. Wullschlager writes of the effect on Chagall: "As news poured in through 1945 of the ongoing Holocaust at Nazi concentration camps,

Bella took her place in Chagall's mind with the millions of Jewish

victims." He even considered the possibility that their "exile from

Europe had sapped her will to live." After

a year of living with his daughter, Ida, and her husband Michel Gordey,

he entered into a romance with Virginia Haggard, great-niece of the

author Henry Rider Haggard; their relationship lasted seven years. They had a child together, David McNeil, born 22 June 1946, Haggard recalled her 'seven years of plenty' with Chagall in her book, My Life with Chagall (Robert Hale, 1986). A

few months after France succeeded in liberating Paris from Nazi

occupation, with the help of the Allied armies, Chagall published a

letter in a Paris weekly, "To the Paris Artists": By 1946 his artwork was becoming more widely recognized. The Museum of Modern Art in New York held

a large exhibition with 40 years of his work which gave visitors one of

the first complete impressions of the changing nature of his art over

the years. The war had by then ended and he began making plans to

return to Paris. According to Cogniat, "He found he was even more

deeply attached than before, not only to the atmosphere of Paris, but

to the city itself, to its houses and its views." Chagall summed up his years living in America: He went back for good in the autumn of 1947, where he attended the opening of the exhibition of his works at the Musée National d'Art Moderne. After returning to France he traveled throughout Europe and chose to live in the Côte d'Azur which by that time had become somewhat of an "artistic centre." Matisse lived above Nice, while Picasso lived in Vallauris.

Although they lived nearby and sometimes worked together, there was

artistic rivalry between them as their work was so distinctly

different, and they never became long-term friends. According to

Picasso's mistress, Françoise Gilot, Picasso still had a great deal of respect for Chagall, and once told her, In

April 1952, Virginia Haggard left Chagall for the photographer Charles

Leirens; she went on to become a professional photographer herself. Chagall's

daughter Ida married art historian Franz Meyer in January 1952, and

feeling that her father missed the companionship of a woman in his

home, introduced him to Valentina (Vava) Brodsky, a woman from a

similar Russian Jewish background, who had run a successful millinery

business in London. She became his secretary, and after a few months

agreed to stay only if Chagall married her. The marriage took place in

July, 1952 -

though six years later, when there was conflict between Ida and Vava,

'Marc and Vava divorced and immediately remarried under an agreement

more favourable to Vava'. In

the years ahead he was able to produce not just paintings and graphic

art, but also numerous sculptures and ceramics, including wall tiles,

painted vases, plates and jugs. He also began working in larger scale

formats, producing large murals, stained glass windows, mosaics and

tapestries. In

1963 Chagall was commissioned to paint the new ceiling for the Paris

Opera, a majestic 19th-century building and national monument. André Malraux,

France's Minister of Culture wanted something unique and decided

Chagall would be the ideal artist. However, this choice of artist led

to controversy: some objected to having a Russian Jew decorate a French

national monument; others took exception to the ceiling of the historic

building being painted by a modern artist. Some magazines wrote

condescending articles about Chagall and Malraux, about which Chagall

commented to one writer: Nonetheless,

Chagall remained on the project which took the 77-year-old Chagall a

year to complete. The final canvas was nearly 2,400 square feet (220

sq. meters) and required 440 pounds of paint. It had five sections

which were glued to polyester panels and hoisted up to the 70-foot

ceiling. The images Chagall painted on the canvas paid tribute to the

composers Mozart, Wagner, Mussorgsky, Berlioz and Ravel, as well as to famous actors and dancers. It

was presented to the public on September 23, 1964 in the presence of

Malraux and 2,100 invited guests. The Paris correspondent for the New York Times wrote, "For once the best seats were in the uppermost circle." Baal-Teshuva writes: After

the new ceiling was unveiled, "even the bitterest opponents of the

commission seemed to fall silent", writes Baal-Teshuva. "Unanimously,

the press declared Chagall's new work to be a great contribution to

French culture." Chagall did not disappoint the trust that Malraux had

placed in him, with Malraux later saying, "What other living artist

could have painted the ceiling of the Paris Opera in the way Chagall

did?.... He is above all one of the great colourists of our time...

many of his canvases and the Opera ceiling represent sublime images

that rank among the finest poetry of our time, just as Titian produced the finest poetry of his day." In Chagall's speech to the audience he explained the meaning of the work: According

to Cogniat, in all Chagall's work during all stages of his life, it was

his colors which attracted and captured the viewer's attention. In his

earlier years his range was limited by his emphasis on form and his

pictures never gave the impression of painted drawings. He adds, "The

colors are a living, integral part of the picture and are never

passively flat, or banal like an afterthought. They sculpt and animate

the volume of the shapes... they indulge in flights of fancy and

invention which add new perspectives and graduated, blended tones....

His colors do not even attempt to imitate nature but rather to suggest

movements, planes and rhythms." He

was able to convey striking images using only two or three colors.

Cogniat writes, "Chagall is unrivalled in this ability to give a vivid

impression of explosive movement with the simplest use of colors...."

Throughout his life his colors created a "vibrant atmosphere" which was

based on "his own personal vision." Chagall's

early life left him with a "powerful visual memory and a pictorial

intelligence", writes Goodman. After living in France and experiencing

the atmosphere of artistic freedom, his "vision soared and he created a

new reality, one that drew on both his inner and outer worlds." But it

was the images and memories of his early years in Russia that would

sustain his art for more than seventy years. According

to Cogniat, there are certain elements in his art that have remained

permanent and seen throughout his career. One of those was his choice

of subjects and the way they were portrayed. "The most obviously

constant element is his gift for happiness and his instinctive

compassion, which even in the most serious subjects prevents him from

dramatization...." Musicians

have been a constant during all stages of his work. After he first got

married, "lovers have sought each other, embraced, caressed, floated

through the air, met in wreaths of flowers, stretched, and swooped like

the melodious passage of their vivid day-dreams. Acrobats contort

themselves with the grace of exotic flowers on the end of their stems;

flowers and foliage abound everywhere." Wullschlager explains the sources for these images: Chagall described his love of circus people: His

early pictures were often of the town where he was born and raised,

Vitebsk. Cogniat notes that they are realistic and give the impression

of firsthand experience by capturing a moment in time with action,

often with a dramatic image. In his later years, as for instance in the

"Bible series", subjects were put on a loftier plane. He managed to

blend the real with the fantastic, and combined with his use of color

the pictures were always at least acceptable if not powerful. He never

attempted to present pure reality but always created his atmospheres

through fantasy. In

all cases Chagall's "most persistent subject is life itself, in its

simplicity or its hidden complexity.... He presents for our study

places, people, and objects from his own life. After absorbing the techniques of Fauvism and Cubism, he was able to blend them with his own folkish style. He gave the grim life of Hasidic Jews the "romantic overtones of a charmed world", notes Goodman. It was by combining the aspects of Modernism with

his "unique artistic language", that he was able to catch the attention

of critics and collectors throughout Europe. Generally, it was his

boyhood of living in a Russian provincial town that gave him a

continual source of imaginative stimuli. Chagall would become one of

many Jewish émigrés who later became noted artists, all

of them similarly having once been part of "Russia's most numerous and

creative minorities", notes Goodman. World War I, which ended in 1918, had displaced nearly a million Jews and destroyed what remained of the provincial shtetl culture that had defined life for most Eastern European Jews for

centuries. Goodman notes, "The fading of traditional Jewish society

left artists like Chagall with powerful memories that could no longer

be fed by a tangible reality. Instead, that culture became an emotional

and intellectual source that existed solely in memory and the

imagination.... So rich had the experience been, it sustained him for

the rest of his life." Sweeney

adds that "if you ask Chagall to explain his paintings, he would reply,

'I don't understand them at all. They are not literature. They are only

pictorial arrangements of images that obsess me...." In

1948, after returning to France from the U.S. after the war, he saw for

himself the destruction that the war had brought to Europe and the

Jewish populations. Some of his art would thereafter reflect his

visions and sadness. In 1951, as part of a memorial book dedicated to

eighty-four Jewish artists who were killed by the Nazis in France, he

wrote a poem entitled "For the Slaughtered Artists: 1950", which

inspired paintings such as the "Song of David": Lewis

writes that Chagall "remains the most important visual artist to have

borne witness to the world of East European Jewry... and inadvertently

became the public witness of a now vanished civilization." Although

Judaism has religious inhibitions about pictorial art of many religious

subjects, Chagall managed to use his fantasy images as a form of visual

metaphor combined with folk imagery. His "Fiddler on the Roof", for

example, combines a folksy village setting with a fiddler as a way to

show the Jewish love of music as important to the Jewish spirit. Art historian Franz Meyer points out that one of the main reasons for the unconventional nature of his work is related to the hassidic movement which inspired the world of his childhood and youth and had actually

impressed itself on most Eastern European Jews since the eighteenth

century. He writes, "For Chagall this is one of the deepest sources,

not of inspiration, but of a certain spiritual attitude... the hassidic

spirit is still the basis and source of nourishment of his art." However, Chagall had a complex relationship with Judaism. On the one hand, he credited his Russian Jewish cultural background as

being crucial to his artistic imagination. But however ambivalent he

was about his religion, he could not avoid drawing upon his Jewish past

for artistic material. As an adult, he was not a practicing Jew, but

through his paintings and stained glass, he continually tried to

suggest a more "universal message", using both Jewish and Christian

themes. The

windows symbolize the twelve tribes of Israel who were blessed by Jacob

and Moses in the verses which conclude Genesis and Deuteronomy. In

those books, notes Leymarie, "The dying Moses repeated Jacob's solemn

act and, in a somewhat different order, also blessed the twelve tribes

of Israel who were about to enter the land of Canaan.... In the

synagogue, where the windows are distributed in the same way, the

tribes form a symbolic guard of honor around the tabernacle." Leymarie describes the physical and spiritual significance of the windows: At the dedication ceremony in 1962, Chagall described his feelings about the windows: For

me a stained glass window is a transparent partition between my heart

and the heart of the world. Stained glass has to be serious and

passionate. It is something elevating and exhilarating. It has to live

through the perception of light. To read the Bible is to perceive a

certain light, and the window has to make this obvious through its

simplicity and grace.... The thoughts have nested in me for many years,

since the time when my feet walked on the Holy Land, when I prepared

myself to create engravings of the Bible. They strengthened me and

encouraged me to bring my modest gift to the Jewish people — that people

that lived here thousands of years ago, among the other Semitic peoples. Chagall

first worked on stage designs in 1914 while living in Russia. It was

during this period in the Russian theatre that formerly static ideas of

stage design were, according to Cogniat, "being swept away in favor of

a wholly arbitrary sense of space with different dimensions, perspectives, colors and rhythms." These

changes appealed to Chagall who had been experimenting with Cubism and

wanted a way to enliven his images. Designing murals and stage designs,

Chagall's "dreams sprang to life and became an actual movement." As

a result, Chagall played an important role in Russian artistic life

during that time and "was one of the most important forces in the

current urge towards anti-realism" which helped the new Russia invent

"astonishing" creations. Many of his designs were done for the Jewish

Theatre in Moscow which put on numerous Jewish plays by playwrights

such as Gogol and Singe. Chagall's set designs helped create illusory atmospheres which became the essence of the theatrical performances. After

leaving Russia, twenty years passed before he was again offered a

chance to design theatre sets. In the years between, his paintings

still included harlequins, clowns and acrobats, which Cogniat notes

"convey his sentimental attachment to and nostalgia for the theatre." His

first assignment designing sets after Russia was for the ballet "Aleko"

in 1942, while living in America. In 1945 he was also commissioned to

design the sets and costumes for Stravinsky's "The Firebird." These designs contributed greatly towards his enhanced reputation in America as a leading artist. Cogniat

describes how Chagall's designs "immerse the spectator in a luminous,

colored fairy-land where forms are mistily defined and the spaces

themselves seem animated with whirlwinds or explosions." His technique of using theatrical color in this way reached its peak when Chagall returned to Paris and designed the sets for Ravel's "Daphnis and Chloë" in 1958. In 1964 he repainted the ceiling of the Paris Opera using 2,400 square feet of canvas, and in 1966 he painted two monumental murals for the outside of the Metropolitan Opera in

New York. The pieces were titled "the Sources of Music" and "The

Triumph of Music", which he completed in France and shipped to New York.

Chagall also designed tapestries which were woven under the direction of Yvette Cauquil-Prince, who also collaborated with Picasso. These tapestries are much rarer than his paintings, with only 40 of them ever reaching the commercial market. Chagall designed three tapestries for the state hall of the Knesset in Israel, along with 12 floor mosaics and a wall mosaic. Chagall began learning about ceramics and sculpture while living in south France. Ceramics became a fashion in the Côte d'Azur with various workshops starting up at Antibes, Vence and Vallauris. He took classes along with other known artists including Picasso and Fernand Léger.

At first Chagall painted existing pieces of pottery but soon expanded

into designing his own, which began his work as a sculptor as a

compliment to his painting. After

experimenting with pottery and dishes he moved into large ceramic

murals. However, he was never satisfied with the limits imposed by the

square tile segments which Cogniat notes "imposed on him a discipline

which prevented the creation of a plastic image." Author

Serena Davies writes that "By the time he died in France in 1985 – the

last surviving master of European modernism, outliving Joan Miró

by two years – he had experienced at first hand the high hopes and

crushing disappointments of the Russian revolution, and had witnessed

the end of the Pale, the near annihilation of European Jewry, and the

obliteration of Vitebsk, his home town, where only 118 of a population

of 240,000 survived the Second World War."

He

came from nowhere to achieve worldwide acclaim. Yet his fractured

relationship with his Jewish identity was "unresolved and tragic",

Davies states. He would have died with no Jewish rites, had not a

Jewish stranger stepped forward and said the kaddish, the Jewish prayer

for the dead, over his coffin."

In 1964 Chagall created a stained-glass window, entitled "Peace", for the United Nations in honor of Dag Hammarskjöld,

the UN's second secretary general who was killed in a plane crash in

Africa in 1961. The window is about 15 feet wide and 12 feet high and

contains symbols of peace and love along with musical symbols. In 1967 he dedicated a stained glass window to John D. Rockefeller in the Union Church of Pocantico Hills, New York. In 1978 he began creating windows for St. Stephen's church in Mainz,

Germany. Today, 200,000 visitors a year visit the church, and "tourists

from the whole world pilgrim up St. Stephen's Mount, to see the glowing

blue stained glass windows by the artist Marc Chagall", states the

city's web site. St. Stephen's is the only German church for which Chagall has created windows."

The

website also notes, "The colours address our vital consciousness

directly, because they tell of optimism, hope and delight in life",

says Monsignor Klaus Mayer, who imparts Chagall's work in mediations

and books. He established contact with Chagall in 1973, and succeeded

in persuading the "master of colour and the biblical message" to set a

sign for Jewish-Christian attachment and international understanding.

Centuries earlier Mainz had been "the capital of European Jewry", and

contained the largest Jewish community in Europe, notes historian John

Man. In 1978, at the age of 91, Chagall fitted the first window and eight more followed. Chagall's co artist Charles Marq complemented Chagall's work by adding

several stained glass windows using the typical colours of Chagall. All Saints’ Tudeley is the only church in the world to have all its twelve windows decorated by Chagall. (The other two religious buildings with complete sets of Chagall windows are the Hadassah Medical Center synagogue and the Chapel of Le Saillant, Limousin.) The

windows at Tudeley are a memorial tribute to Sarah d'Avigdor-Goldsmid

who died in 1963 aged just 21 in a sailing accident off Rye. Sarah was

the daughter of Sir Henry d'Avigdor-Goldsmid and Lady Rosemary who commissioned Chagall to design the magnificent east window, which was installed in 1967. Over

the next 15 years, Chagall designed the remaining windows, again made

in collaboration with the glassworker Charles Marq in his workshop at

Reims in northern France.