<Back to Index>

- Physician James Young Simpson, 1811

- Architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh, 1868

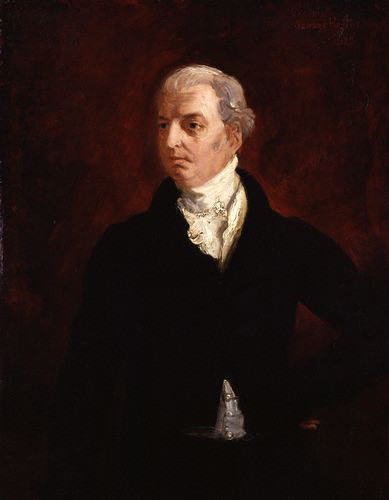

- Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool, 1770

PAGE SPONSOR

Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool KG PC (7 June 1770 – 4 December 1828) was a British politician and the longest serving Prime Minister of the United Kingdom since the Union with Ireland in 1801. He was forty-two years old when he became premier in 1812 which made him younger than all of his successors to date (the next-youngest being David Cameron, taking office at 43). During his time as Prime Minister from 1812 to 1827, Liverpool became known for repressive measures introduced to maintain order, but also for steering the country through the period of radicalism and unrest that followed the Napoleonic Wars.

Important events during his tenure as Prime Minister included the War of 1812, the Sixth and Seventh Coalitions against the French Empire, the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars at the Congress of Vienna, the Corn Laws, the Peterloo Massacre, the Trinitarian Act 1812 and the emerging issue of Catholic Emancipation.

Jenkinson was baptised on 29 June 1770 at St. Margaret's, Westminster, the son of George III's close adviser Charles Jenkinson, 1st Earl of Liverpool and his first wife, Amelia Watts. Jenkinson's 19 year old mother, who was the part-Indian daughter of a senior East India Company official William Watts, died from the effects of childbirth one month after his birth. Jenkinson was educated at Charterhouse School and Christ Church, Oxford. In the summer of 1789, Jenkinson spent four months in Paris to perfect his French and

enlarge his social experience. He returned to Oxford for three months

to complete his terms of residence and in May 1790 was created master

of arts. He won election to the House of Commons in 1790 for Rye,

a seat he would hold until 1803; at the time, however, he was under the

age of assent to Parliament, so he refrained from taking his seat and

spent the following winter and early spring in an extended tour of the

continent. This tour took in the Netherlands and Italy,

whereby he was old enough to take his seat in Parliament. It is not

clear exactly when he entered the Commons, but as his twenty-first

birthday was not reached until almost the end of the 1791 session, it

is possible that he waited until the following year. With

the help of his father's influence and his political talent, he rose

relatively fast in the Tory government. In February 1792, he gave the

reply to Samuel Whitbread's critical motion on the government's Russian policy. He delivered several other speeches during the session, including one against the abolition of the slave trade, which reflected his father's strong opposition to William Wilberforce's campaign. He served as a member of the Board of Control for India from 1793 to 1796.

In the defence movement that followed the outbreak of hostilities with France, Jenkinson, was one of the first of the ministers of the government to enlist in the militia. In 1794 he became a Colonel in the Cinque Ports fencibles, and his military duties led to frequent absences from the Commons. In 1796 his regiment was sent to Scotland and he was quartered for a time in Dumfries.

His parliamentary attendance also suffered from his reaction when his

father angrily opposed his projected marriage with Lady Louisa Hervey, daughter of the Earl of Bristol. After Pitt and the King had intervened on his behalf, the wedding finally took place at Wimbledon on 25 March 1795. In May 1796, when his father was created Earl of Liverpool, he took the courtesy title of Lord Hawkesbury in 1796 and remained in the Commons. He became Baron Hawkesbury in

his own right and was elevated to the House of Lords in November 1803,

as recognition of his work as Foreign Secretary. He also served as Master of the Mint (1799 – 1801).

In Henry Addington's government, he entered the cabinet as Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, in which capacity he negotiated the Treaty of Amiens with France. Most of his time as Foreign secretary was spent dealing with the nations of France and the United States. He continued to serve in the cabinet as Home Secretary in Pitt the Younger's second

government. While Pitt was seriously ill, Liverpool was in charge of

the cabinet and drew up the King's Speech for the official opening of

Parliament. When William Pitt died in 1806, the King asked Liverpool to

accept the post of Prime Minister, but he refused, as he believed he

lacked a governing majority. He was then made leader of the Opposition

during Lord Grenville's

ministry (the only time that Liverpool did not hold government office

between 1793 and after his retirement). In 1807, he resumed office as Home Secretary in the Duke of Portland's ministry.

Lord Liverpool (as Hawkesbury had now become by the death of his father in December 1808) accepted the position of Secretary of State for War and the Colonies in Spencer Perceval's government in 1809. Liverpool's first step on taking up his new post was to elicit from the Duke of Wellington a

strong enough statement of his ability to resist a French attack to

persuade the cabinet to commit themselves to the maintenance of his

small force in Portugal.

When

Perceval was assassinated in May 1812, Lord Liverpool succeeded him as

prime minister. The cabinet proposed Liverpool as his successor with Lord Castlereagh as

leader in the Commons. But after an adverse vote in the Lower House,

they subsequently gave both their resignations. The Prince Regent,

however, found it impossible to form a different coalition and

confirmed Liverpool as prime minister on 8 June. Liverpool's government

contained some of the future great leaders of Britain, such as Lord Castlereagh, George Canning, the Duke of Wellington, Robert Peel, and William Huskisson.

Liverpool is considered a skilled politician, and held together the

liberal and reactionary wings of the Tory party, which his successors,

Canning, Goderich and Wellington, had great difficulty with.

Liverpool's ministry was a long and eventful one. The War of 1812 with

the United States and the final campaigns of the Napoleonic Wars were

fought during Liverpool's premiership. It was during his ministry that

the Peninsular Campaigns were fought by the Duke of Wellington. Britain

defeated France in the Napoleonic Wars,

and Liverpool was awarded the Order of the Garter. At the peace

negotiations that followed, Liverpool's main concern was to obtain a

European settlement that would ensure the independence of the Netherlands, Spain and Portugal, and confine France inside

her pre-war frontiers without damaging her national integrity. To

achieve this, he was ready to return all British colonial conquests.

Within this broad framework, he gave Castlereagh a discretion at the Congress of Vienna,

the next most important event of his ministry. At the congress, he gave

prompt approval for Castlereagh's bold initiative in making the

defensive alliance with Austria and France in January 1815. In the aftermath, many years of peace followed. Agriculture

remained a problem because good harvests between 1819 and 1822 had

brought down prices and evoked a cry for greater protection. When the

powerful agricultural lobby in Parliament demanded protection in the

aftermath, Liverpool gave in to political necessity. Under governmental

supervision the notorious Corn Laws of 1815 were passed prohibiting the import of foreign wheat until

the domestic price reached a minimum accepted level. Liverpool,

however, was in principle a free-trader, but had to accept the bill as

a temporary measure to ease the transition to peacetime conditions. His

chief economic problem during his time as Prime Minister was that of

the nation's finances. The interest on the national debt, massively swollen by the enormous expenditure of the final war years, together with the war pensions, absorbed the greater part of normal government revenue. The refusal of the House of Commons in

1816 to continue the wartime income tax left ministers with no

immediate alternative but to go on with the ruinous system of borrowing

to meet necessary annual expenditure. Liverpool eventually facilitated

a return to the gold standard in 1819. Inevitably

taxes rose to compensate for borrowing and to pay off the debt, which

led to widespread disturbance between 1812 and 1822. Around this time,

the group known as Luddites began industrial action, by smashing industrial machines developed for use in the textile industries of the West Riding of Yorkshire, Nottinghamshire, Leicestershire and Derbyshire.

Throughout the period 1811 - 16, there were a series of incidents of

machine breaking and many of those convicted faced execution. The

reports of the secret committees he obtained in 1817 pointed to the

existence of an organised network of disaffected political societies,

especially in the manufacturing areas. Liverpool told Peel that the

disaffection in the country seemed even worse than in 1794. Because of

a largely perceived threat to the government, temporary legislation was

introduced. He suspended Habeas Corpus in both Great Britain (1817) and Ireland (1822). Following the Peterloo Massacre in 1819, his government imposed the repressive Six Acts legislation which limited, among other things, free speech and the right to gather for peaceful demonstration. In 1820, as a result of these measures, Liverpool and other cabinet ministers were almost assassinated in the Cato Street Conspiracy. Although

Lord Liverpool argued for the abolition of the slave trade at the

Congress of Vienna, he was generally opposed to reform at home, often

embracing repressive measures to ensure the status quo. He did however support the repeal of the Combination Laws banning workers from combining into trade unions in 1824, although the powers of these unions were restricted in 1825 following strikes. During the 19th century, and, in particular, during Liverpool's time in office, Catholic emancipation was

a source of great conflict. In 1805, in his first important statement

of his views on the subject, Liverpool had argued that the special

relationship of the monarch with the Church of England, and the refusal

of Roman Catholics to

take the oath of supremacy, justified their exclusion from political

power. Throughout his career, he remained opposed to the idea of

Catholic emancipation, though did see marginal concessions as important

to the stability of the nation. The decision of 1812 to remove the

issue from collective cabinet policy, followed in 1813 by the defeat of

Grattan's Roman Catholic Relief Bill,

brought a period of calm. Liverpool supported marginal concessions such

as the admittance of English Roman Catholics to the higher ranks of the

armed forces, the magistracy, and the parliamentary franchise; but he

remained opposed to their participation in parliament itself. In the

1820s, pressure from the liberal wing of the Commons and the rise of

the Catholic Association in Ireland revived the controversy. By

the date of Sir Francis Burdett's Catholic Relief Bill in 1825,

emancipation looked a likely success. Indeed, the success of the bill

in the Commons in April, followed by Robert Peel's

tender of resignation, finally persuaded Liverpool that he should

retire. When Canning made a formal proposal that the cabinet should

back the bill, Liverpool was convinced that his administration had come

to its end. George Canning then succeeded him as Prime Minister. Catholic emancipation however was not fully implemented until the major changes of the Catholic Relief Act of 1829 under the leadership of the Duke of Wellington and Sir Robert Peel, and with the work of the Catholic Association established in 1823. Liverpool's

first wife, Louisa, died at 54. He soon married again to Lady Mary

Chester, a long time friend of Louisa. Their marriage only lasted three

years however, until Liverpool's death. Liverpool finally retired on 9

April 1827, when, at Fife House (his riverside residence in Whitehall since

1810), he suffered a severe cerebral hemorrhage, and asked the King to

seek a successor. There was another minor stroke in July, after which

he lingered on at Coombe until a third and fatal attack on 4 December

1828 when he died. He had no children and was succeeded in the Earldom of Liverpool by his younger half brother Charles Cecil Cope Jenkinson, 3rd Earl of Liverpool. He was buried in Hawkesbury parish church, Gloucestershire, beside his

father and his first wife. His personal estate was registered at under

£120,000. Liverpool Street in London is named after Lord Liverpool.