<Back to Index>

- Astronomer Giovanni Domenico Cassini, 1625

- Composer Robert Schumann, 1810

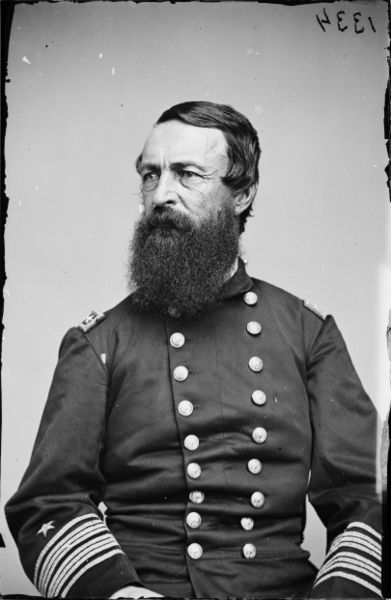

- Admiral David Dixon Porter, 1813

PAGE SPONSOR

David Dixon Porter (June 8, 1813 – February 13, 1891) was a member of one of the most distinguished families in the history of the United States Navy. When he was 10 years old, his father, Commodore David Porter, took David Dixon aboard his ship, frigate John Adams, for a cruise and ordered his officers to submit his son to the discipline of a midshipman. For the remainder of his life, he was associated with the sea.

He

served in the Mexican War in the attack on the fort at Vera Cruz. At

the outbreak of the Civil War, he formulated and participated in a plan

to hold Fort Pickens, near Penacola, Florida, for the Union; its

execution disrupted the simultaneous effort to relieve the garrison at

Fort Sumter, in the harbor at Charleston, South Carolina, and hence led

to the fall of that fort. He commanded a somewhat independent flotilla

of mortar boats at the capture of New Orleans.

Later, he was advanced to the rank of (acting) rear admiral in command

of the Mississippi River Squadron, which cooperated with the army under

Major General Ulysses S. Grant in the Vicksburg campaign. After the successful conclusion of that operation, he led the naval forces in the Red River campaign that

almost ended disastrously. Late in 1864, he was transferred from the

interior to the Atlantic coast, where he led the navy in the joint

assaults on Fort Fisher, the final significant naval action of the war. With

the return of peace, he became active in the effort to render the US

Navy respectable in comparison with the best of the world's navies. He

was appointed superintendent of the Naval Academy when it was restored

to Annapolis, and there he instituted reforms in the curriculum to instill principles

of professionalism. In the early days of the administration of President Grant, he was de facto secretary of the navy. When David G. Farragut was

advanced from rank of vice-admiral to admiral, Porter took his previous

position; likewise, when Farragut retired, Porter became the second man

to hold the rank of admiral. He gathered about himself a corps of

like-minded officers devoted to naval reform. Porter's administration

of the Navy Department aroused opposition in Congress, and soon

Secretary of the Navy Adolph E. Borie was forced to resign. His replacement, George Robeson, curtailed his power and eased him into semi-retirement. He died on February 13, 1891. David Dixon Porter was born in Chester, Pennsylvania, on

June 8, 1813, a son of David Porter and Evalina Anderson Porter. The

family had strong naval traditions; the elder Porter's father, also

named David, had been captain of a Massachusetts vessel in the American Revolutionary War,

as had his uncle Samuel. Both the second David Porter, David Dixon's

father, and his brother John entered the fledgling United States Navy

and served with distinction during the War of 1812. David eventually rose to the rank of captain,

the highest rank awarded in the US Navy prior to the Civil War.

Following the war, he was given increased responsibilities and gained

the courtesy title of Commodore. David

and Evalina Porter had 10 children, including six boys. The youngest,

Thomas, died of yellow fever at the age of ten. The other five all

became officers, four in the US Navy (William, David Dixon, Hambleton,

and Henry Ogden), and one, Theodoric, in the US Army. Hambleton died at

sea of yellow fever while yet a passed midshipman. Theodoric was killed

at Matamoros in the Mexican War; David Dixon later named his second son

Theodoric in memory of his brother. John Porter was not so prolific, but one of his sons, Fitz John Porter, was a major general in the US Army at the time of the Civil War, and a second, Bolton Porter, was lost with his ship USS Levant. Their

sister Anne, who married her cousin Alexander Porter, provided a son,

David Henry Porter, who was killed while captain of a Mexican ship

during that nation's struggle for independence from Spain. The

tradition continued into later generations. David Dixon married George

Ann ("Georgy") Patterson, daughter of Commodore Daniel T. Patterson. Of

their four sons, three had military careers. Major David Essex Porter

served in the army during the Civil War, but resigned after two years

in the peacetime army. Captain Theodoric Porter made his career in the

navy. Lieutenant Colonel Carlile Patterson Porter was an officer in the

US Marine Corps; his son, David Dixon Porter II,

also served in the Marines, rising to the rank of major general and

earning the Medal of Honor. One of their two surviving daughters,

Elizabeth, was married to Rear Admiral Leavitt Curtis Logan. Commodore

Porter also had an adoptive son who later was closely associated with

the career of David Dixon. In the early years of the nineteenth

century, the commodore was stationed at New Orleans, and his father

accompanied the family there in his declining years. There, the older

David Porter met and became friends with another former naval

participant in the Revolution, George Farragut. In

late spring 1808, David Porter Sr. suffered sunstroke, and Farragut

took him into his home, where Elizabeth Farragut cared for him. She

could not restore him to health, however (he was already weakened by

tuberculosis), and he died on June 22, 1808. Perhaps ironically,

Elizabeth Farragut died of yellow fever on the same day. Now

motherless, the Farragut children were scattered around into the homes

of friends and relatives. While he was visiting the family a short time

later to express appreciation for the kindness they had shown his

father and sympathy for the loss of their wife and mother, Commodore

Porter offered to take eight year old James Glasgow Farragut into his

own household. Young James readily agreed. Next year, he moved with

Porter to Washington, where he met Secretary of the Navy Paul Hamilton

and expressed his wish for a midshipman's appointment. Hamilton

promised that the appointment would be made as soon as he reached the

age of ten; as it happened, the commission came through on December 17,

1810, six months before the boy reached his tenth birthday. When James

went to sea soon after with his adoptive father, he changed his name

from James to David, and it is as David Glasgow Farragut that he is remembered. Commodore

David Porter was reprimanded by the navy for an 1824 incident that

humiliated an official of the Spanish government in Cuba. Although the

punishment was minimal, he decided to resign from the navy rather than

submit, and he then accepted an offer from the government of Mexico to

become their General of Marine – in effect, the commander of their

entire navy. Among

the several US citizens whom he took along to his new position were a

nephew, David Henry Porter, and two sons, David Dixon and Thomas. The

two boys were made midshipmen. Unfortunately, Thomas died of yellow

fever soon after arriving in Mexico; he was ten years of age. David

Dixon, age 12, was not affected by the disease. He was able to serve on

the frigate Libertad, where he saw little action, and on the captured merchantman Esmeralda for a raid on Spanish shipping in Cuban waters. In 1828, he was able to accompany his cousin, David Henry Porter, captain of the brig Guerrero, in another raid. Guerrero, mounting

22 guns, was one of the finest vessels in the small Mexican Navy. Off

the coast of Cuba on February 10, 1828, she encountered a flotilla of

about fifty schooners, convoyed by Spanish brigs Marte and Amalia. Captain

Porter elected to attack, and soon forced the flotilla to seek refuge

in the harbor at Mariel, 30 miles (48 km) west of Havana. The

noise of battle was heard in Havana, and there the 64-gun frigate Lealtad put to sea. Guerrero was

able to break off the action and escape, but overnight Captain Porter

rashly decided to circle back and attack the vessels still at Mariel.

Intercepted again by Lealtad, he

could not escape this time. In the course of the ensuing battle,

Midshipman Porter received his first (minor) wound, and Captain Porter

was killed, together with many of his crew. The survivors surrendered

and were imprisoned in Havana until they could be exchanged. Commodore

Porter chose not to risk his son again, and sent him back to the United

States by way of New Orleans. David

Dixon Porter obtained an official appointment as midshipman in the US

Navy through his grandfather, Congressman William Anderson. The

appointment was dated February 2, 1829, when he was sixteen years of

age; this was somewhat older than most midshipmen of the time. His

relative maturity and his experience, already greater than that of most

naval lieutenants, bred in him a certain cockiness and willingness to

challenge those above him. As a result, his warrant as a midshipman

would not have been renewed except for extraordinary intervention by

Commodore James Biddle, who acted favorably not because Porter deserved

it but because his father was a hero. Porter's last duty as a midshipman was on frigate USS United States, flagship of Commodore Daniel Patterson,

on a cruise that lasted from June 1832 until October 1834. The major

importance of the cruise for Porter was that Patterson's family

accompanied him. The family included his daughter, George Ann

("Georgy"), and the two young people renewed their acquaintance.

Although marriage would have to wait, the couple became engaged. After Porter returned home, he completed the examination for passed midshipman,

and soon after was assigned to duty in the Coast Survey. There, his pay

was such that he could save enough to marry. He and Georgy were united on March 10, 1839. In

March 1841, he was advanced in rank to lieutenant, and in April of the

next year he was detached from the Coast Survey. He had a brief tour of

duty in the Mediterranean, and then he was assigned to the US Navy's

Hydrographic Office.

In

1846, the era of peace was coming to a close. The United States had

annexed the Republic of Texas, and the islands of the Caribbean seemed

to be likely targets for further expansion. The Republic of Santo

Domingo (the present-day Dominican Republic) had broken off from the Republic of Haiti in

1844, and the United States State Department needed to determine the

new nation's social, political, and economic stability. The suitability

of the Bay of Samana for US Navy operations was also of interest. To

find out, Secretary of State James Buchanan asked

Porter to undertake a private investigation. He accepted the

assignment, and on March 15, 1846, he left home. He arrived in Santo

Domingo after some unexpected delays and spent two weeks mapping the

coastline. On May 19, he began a trek through the interior that left

him without communication for a month. On June 19, he emerged from the

jungle, bitten by insects, but with the information that the State

Department wanted. He then discovered that while he was away the United

States had gone to war with Mexico. Mexico

did not have a real navy, so naval personnel had little opportunity for

distinction. Porter served as first lieutenant of the sidewheel gunboat USS Spitfire under Commander Josiah Tattnall. Spitfire was at Vera Cruz when General Winfield Scott led

the amphibious assault on the city, which was shielded by a series of

forts and the ancient Castle of San Juan de Ulloa. Porter had spent

many hours exploring the castle when he had been a midshipman in the

Mexican Navy, so he was familiar with both its strengths and its

weaknesses. He submitted a plan to attack it to Captain Tattnall.

Taking eight oarsmen and the ship's gig, he sounded out a channel on

the night of March 22–23, 1847, using the experience he had gained with

the Coast Survey. The next morning, Spitfire and

other vessels taking part in the bombardment followed the channel that

Porter had laid out and took up positions inside the harbor, where they

were able to pound the forts and castle. Doing so meant, however, that

they had to run by the forts, which was contrary to the orders of

Commodore Matthew C. Perry.

Perry sent signals ordering the vessels to break off the bombardment

and return, but Tattnall ordered his men not to look at the commodore's

signals. Not until a special messenger came with explicit orders to

retire did Maffitt cease firing. Perry appreciated the audacity shown

by his subordinates, but did not approve of the way they had

disregarded his orders. Henceforth, he kept Spitfire by his side. In

June, Perry mounted an expedition to capture the interior town of

Tabasco. Porter on his own led a charge of 68 sailors to capture the

fort defending the city. Perry rewarded him for his initiative by

making him captain of Spitfire. It was his first command. It brought him no advantages, however, as the naval part of the war was essentially over. In

Washington again following the war, Porter had little chance for

professional improvement and none for advancement. In order to gain

experience in handling steamships, he took leave of absence from the

Navy to command civilian ships. He insisted that his crews submit to

the methods of military discipline; his employers were noncommittal

about his methods, but they were impressed by the results. They asked

him to stay in Australia, but his health and the health of his eldest

daughter Georgianne persuaded him to return. Back in the United States,

he moved his family from Washington to New York in hope that the

climate would benefit his daughter, but she died shortly after the

move. His second daughter, Evalina ("Nina") also died in the interwar

period. Once again on active duty, he commanded the storeship USS Supply in a venture to bring camels to the United States. The project was promoted by Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, who thought that the desert animals could be useful for the cavalry in the arid Southwest. Supply made two successful trips before Secretary Davis left office and the experiment was discontinued. In 1859, he received an attractive offer from the Pacific Mail Steamship Company to

be captain of a ship then under construction. The offer would be

effective when she was complete. He would have accepted, but he was

delayed in his departure. Before he could leave, war had broken out

again. The seceded states laid

claim to the national forts within their boundaries, but they did not

make good their claim to Fort Sumter in South Carolina and Forts

Pickens, Zachary Taylor, and Jefferson in Florida. They soon made it clear that they would use force if necessary to gain possession of Fort Sumter and Fort Pickens. President Abraham Lincoln resolved not to cede them without a fight. Secretary of State William H. Seward, Captain Montgomery C. Meigs of

the US Army, and Porter devised a plan for the relief of Fort Pickens.

The principal element of their plan required use of the steam frigate USS Powhatan,

which would be commanded by Porter and would carry reinforcements to

the fort from New York. Because no one was above suspicion in those

days, the plan had to be implemented in complete secrecy; not even

Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles was to be advised. Welles was in the meantime preparing an expedition for the relief of the garrison at Fort Sumter. As he was unaware that Powhatan would

not be available, he included it in his plans. When the other vessels

assigned to the effort showed up, the South Carolina troops at

Charleston began to bombard Fort Sumter, and the Civil War was on. The

relief expedition could only wait outside the harbor. The expedition

had little chance to be successful in any case; without the support of

the guns on Powhatan, it

was completely impotent. The only contribution made by the expedition

was to carry the soldiers who had defended Fort Sumter back to the

North following their surrender and parole. Lincoln

did not punish Seward for his part in the incident, so Welles felt that

he had no choice but to forgive Porter, whose culpability was less.

Later, he reasoned that it had at least a redeeming feature in that

Porter, whose loyalty had been suspect, was henceforth firmly attached

to the Union. As he wrote, In late 1861, the Navy Department began to develop plans to open the Mississippi River. The first move would be to capture New Orleans, Louisiana.

For this Porter, by this time advanced to rank of commander, was given

the responsibility of organizing a flotilla of some twenty mortar boats

that would participate in the reduction of the forts defending the city

from the south. The flotilla was a semi-autonomous part of the West Gulf Blockading Squadron, which was to be commanded by Porter's adoptive brother Captain David G. Farragut. The

bombardment of Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip began on April 18,

1862. Porter had opined that two days of concentrated fire would be

enough to reduce the forts, but after five days they seemed as strong

as ever. The mortars were beginning to run low on ammunition. Farragut,

who put little reliance on the mortars anyway, made the decision to

bypass the forts on the night of April 24. The fleet successfully ran

past the forts; the mortars were left behind, but they bombarded the

forts during the passage in order to distract the enemy gunners. Once

the fleet was above the forts, nothing significant stood between them

and New Orleans; Farragut demanded the surrender of the city, and it

fell to his fleet on April 29. The forts were still between him and

Porter's mortar fleet, but when the latter again began to pummel Fort

Jackson, its garrison mutinied and forced its surrender. Fort St.

Philip had to follow suit. Surrender of the two forts was accepted by

Commander Porter on April 28. Following

orders from the Navy Department, Farragut took his fleet upstream to

capture other strongpoints on the river, with the aim of complete possession of the Mississippi. At Vicksburg, Mississippi, he

found that the bluffs were too high to be reached by the guns of his

fleet, so he ordered Porter to bring his mortar flotilla up. The

mortars suppressed the Rebel artillery well enough that Farragut's

ships could pass the batteries at Vicksburg and link up with a Union flotilla coming

down from the north. The city could not be taken, however, without

active participation by the army, which did not happen. On July 8, the

bombardment ceased when Porter was ordered to Hampton Roads to assist

in Major General George B. McClellan's Peninsula campaign. A few days later, Farragut followed, and the first attempt to take Vicksburg was over. In

the summer of 1862, shortly after Porter left Vicksburg, the US Navy

was extensively modified; among the features of the revised

organization were a set of officer ranks from ensign to rear admiral

that paralleled the ranks in the Army. Among the new ranks created were those of commodore and rear admiral. According

to the organization charts, the persons in command of the blockading

squadrons were to be rear admirals. Another part of the reorganization

transferred the Western gunboat flotilla from the army to the navy, and retitled it the Mississippi River Squadron.

The change of title implied that it was formally equivalent to the

other squadrons, so its commanding officer would likewise be a rear

admiral. The problem was that the commandant of the gunboat flotilla,

Flag Officer Charles H. Davis,

had not shown the initiative that the Navy Department wanted, so he had

to be removed. He was made rear admiral, but he was recalled to

Washington to serve as chief of the Bureau of Navigation. Most

of the men who could have replaced Davis were either less suitable or

were unavailable because of other assignments, so finally Secretary

Welles decided to appoint Porter to the position. He did this despite

some doubt. As he wrote in his Diary, Thus

Commander Porter became Acting Rear Admiral Porter without going

through the intermediate ranks of captain and commodore. He left

Washington for his new command on October 9 and arrived in Cairo, Illinois, on October 15. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton considered Porter "a gas bag . . . blowing his own trumpet and stealing credit which belongs to others." Historian John D. Winters, in his The Civil War in Louisiana,

describes Porter as having "possessed the qualities of abundant energy,

recklessness, resourcefulness, and fighting spirit needed for the

trying role ahead. Porter was assigned the task of aiding General John A. McClernand in

opening the upper Mississippi. The choice of McClernand, a volunteer

political general, pleased Porter because he felt that all West Point men were 'too self-sufficient, pedantic, and unpractical.'" Winters

also writes that Porter "revealed a weakness he was to display many

times: he belittled a superior officer [Charles H. Poor]. He often

heaped undue praise upon a subordinate, but rarely could find much to

admire in a superior." The

Army was showing renewed interest in opening the Mississippi River at

just this time, and Porter met two men who would have great influence

on the campaign. First was Major General William T. Sherman, a man of similar temperament to his own, with whom he immediately formed a particularly strong friendship. The other was Major General McClernand, whom he just as quickly came to dislike. Later they would be joined by Major General Ulysses S. Grant;

Grant and Porter became friends and worked together quite well, but it

was on a more strictly professional level than his relation with

Sherman. Close

cooperation between the Army and Navy was vital to the success of the

siege of Vicksburg. The most prominent contribution to the campaign was

the passage of the batteries at Vicksburg and Grand Gulf by a major

part of the Mississippi River Squadron. Grant had asked merely for a

few gunboats to shield his troops, but Porter persuaded him to use more

than half of his fleet. After nightfall on April 16, 1863, the fleet

moved past the batteries. Only one vessel was lost in the ensuing

firefight. Six nights later, a similar run past the batteries gave

Grant the transports he needed for crossing the river. Now

south of Vicksburg, Grant at first tried to attack the Rebels through

Grand Gulf, and requested Porter to eliminate the batteries there

before his troops would be sent across. On April 29, the gunboats spent

most of the day bombarding two Confederate forts. They succeeded in

silencing the lower of the two, but the upper fort remained. Grant

called off the assault and moved downstream to Bruinsburg, where he was

able to cross the river unopposed. Although

the fleet made no major offensive contributions to the campaign after

Grand Gulf, it remained important in its secondary role of keeping the

blockade against the city. When Vicksburg was besieged, the

encirclement was made complete by the Navy's control of the Mississippi

and Yazoo Rivers. When it finally fell on July 4, Grant was unstinting

in his praise of the assistance he had received from Porter and his men. For his contribution to the victory, Porter's appointment as "acting" rear admiral was made permanent, dated from July 4. After the opening of the Mississippi, the political general Nathaniel P. Banks,

who was in charge of army forces in Louisiana, brought pressure on the

Lincoln administration to mount a campaign across Louisiana and into

Texas along the line of the Red River. The ostensible purpose was to

extend Union control into Texas, but

Banks was influenced by numerous speculators to convert the campaign

into little more than a raid to seize cotton. Admiral Porter was not in

favor; he thought that the next objective of his fleet should be to

capture Mobile, but he received direct orders from Washington to

cooperate with Banks. After

considerable delays caused by Banks's attention to political rather

than military matters, the Red River expedition got under way in early

March 1864. From the start, navigation of the river presented as great

a problem for Porter and his fleet as did the Confederate army that

opposed them. The army under Banks and the navy under Porter did little

to cooperate, and instead often became rivals in a race to seize

cotton. The Rebel opposition under Major General Richard Taylor succeeded in keeping them apart by defeating Banks at a small place known as Pleasant Hills,

following which Banks gave up the expedition. From that time on,

Porter's primary task was to extricate his fleet. The task was made

difficult by falling water levels in the river, but he ultimately got

most out, with the help of heroic efforts by some of the soldiers who

stayed to protect the fleet. By late summer 1864, Wilmington, North Carolina was the only port open for running the blockade, and the Navy Department began to plan to close it. Its major defense was Fort Fisher, a massive structure at the New Inlet to the Cape Fear River. Secretary Welles believed that the head of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, Rear Admiral Samuel Phillips Lee,

was inadequate for the task, so he at first assigned Rear Admiral

Farragut to be Lee's replacement. Farragut was too ill to serve,

however, so Welles then decided to switch Lee with Porter: Lee would

command the Mississippi River Squadron, and Porter would come east and

prepare for the attack on Fort Fisher. The

planned attack on Fort Fisher required the cooperation of the army, and

the troops were taken from the Army of the James. It was expected that

Brigadier General Godfrey Weitzel would command, but Major General Benjamin F. Butler,

the commandant of the Army of the James, exercised one of the

prerogatives of his position to install himself as leader of the

expedition. Butler proposed that the fort could be flattened by

exploding a ship filled with gunpowder near it, and Porter accepted the

idea; if successful, the scheme would avoid a protracted siege or its

alternative, a frontal assault. Accordingly, the old steamer USS Louisiana was

packed with powder and blown up in the early morning of December 24,

1864. It had, however, no discernible effect on the fort. Butler

brought part of his troops ashore, but he was already convinced that it

was hopeless, so he removed his force before making an all-out assault. Porter,

enraged by Butler's timorousness, went to U. S. Grant and demanded that

Butler be removed. Grant agreed, and placed Major General Alfred H. Terry in

charge of a second assault on the fort. The second assault began on

January 13, 1865, with unopposed landings and bombardment of the fort

by the fleet. Porter imposed new methods of bombardment this time: each

ship was assigned a specific target, with intent to destroy the enemy's

guns rather than to knock down the walls. They were also to continue

firing after the men ashore started their assault; the ships would

shift their aim to points ahead of the advancing troops. The

bombardment continued for two more days, while Terry got his men into

position. On the 15th, frontal assaults on opposite faces by Terry's

soldiers on the land side and 2000 sailors and marines on the beach

vanquished the fort. This was the last significant naval operation of

the war.

The

US Navy was rapidly downsized at the end of the war, and Porter, like

most of his contemporaries, had no more ships to command. Some feared

that at sea he might provoke a foreign war, particularly with Great

Britain, because of what he saw as their support for the Confederacy.

To make use of his undeniable talents, Secretary Welles appointed him

superintendent of the Naval Academy in 1865. The academy at that time

did little to prepare men for the duties that were expected of them.

Porter resolved to change that; he determined to make the Academy the

rival of the Military Academy at West Point. The curriculum was revised

to reflect the reality of naval life, organized sports were encouraged,

discipline was enforced, and even social graces were taught. An honor

system was installed, "to send honorable men from this institution into

the Navy." To

be sure that his reforms would remain in place after his departure, he

brought to the faculty a group of like-minded men, mostly young

officers who had distinguished themselves in the war.

When Porter's friend Ulysses S. Grant became president in 1869, he appointed Philadelphia businessman Adolph E. Borie as

Secretary of the Navy. Borie had no knowledge of the navy and little

desire to learn, so he leaned on Porter for advice that the latter was

quite willing to give. In a short time, Borie came to defer to him even

on trivial routine matters. Porter used his influence with the

secretary to push through several policies to shape the navy as he

wanted it; in the process, he made a new set of enemies who either were

harmed by his actions or merely resented his blunt methods. Borie was

strongly criticized for his failure to control his subordinate, and

after three months he resigned. The new secretary, George Robeson, promptly curtailed Porter's powers. In

1866, the ranks of admiral and vice admiral were created in the US

Navy. Naval hero Farragut was named as the nation's first admiral, and

Porter became vice admiral at the same time. In 1871, Farragut died,

and it was expected that Porter would be promoted to fill the vacancy.

Eventually, he did become the second admiral, but it was after much

controversy that was provoked by his many enemies. Among them were

several very powerful politicians, including some of the political

generals he had contended with in the war. Despite

the prestige of the high rank, his eclipse continued. For the last

twenty years of his life, he had little to do with the operations of

the navy. He turned to writing, producing some histories that are of

doubtful reliability but provide insights into his own beliefs and

character. He also wrote some fiction of a sort that has not withstood

the test of time. After twenty years of semi-retirement, his health

began to give way. In the summer of 1890 he suffered a heart attack; he

survived but was clearly in decline. He died on the morning of February 13, 1891.