<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Paul Guldin, 1577

- Composer Rikard Nordraak, 1842

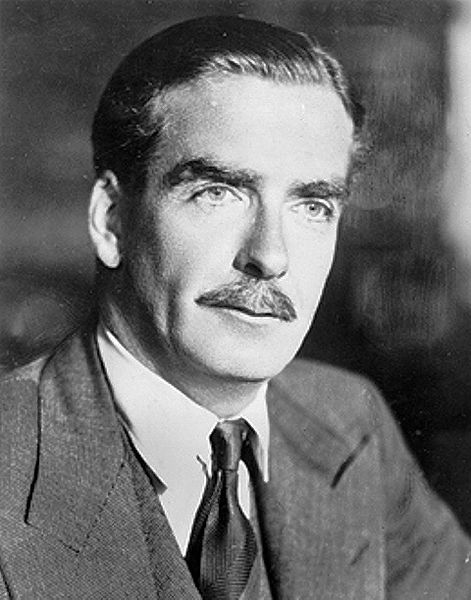

- Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Robert Anthony Eden, 1897

PAGE SPONSOR

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon, KG, MC, PC (12 June 1897 – 14 January 1977) was a British Conservative politician, who was Prime Minister from 1955 to 1957. He was also Foreign Secretary for three periods between 1935 and 1955, including during the Second World War.

Eden's worldwide reputation as an opponent of appeasement, a 'Man of Peace', and a skilled diplomat was overshadowed in the second year of his premiership by his handling of the Suez Crisis of 1956, which critics across party lines regarded as an historic setback for British foreign policy, signalling the end of British predominance in the Middle East. In the post-war years, Eden was a protagonist of the change in British policy on war criminal trials, which was perhaps best symbolised by his signature under the pardon conceded to the German Field Marshal Albert Kesselring on 24 October 1952. He is generally ranked among the least successful British Prime Ministers of the twentieth century, although two broadly sympathetic biographies (in 1986 and 2003) have gone some way to redressing the balance of opinion.

Eden was born at Windlestone Hall, County Durham, England, into a very conservative landed gentry family. He was a younger son of Sir William Eden, baronet, from an old titled family. His mother, Sybil Frances Grey, was a member of the famous Grey family of Northumberland. This was perhaps the meaning of Rab Butler's

later gibe that Eden – in later life a handsome but ill-tempered man –

was "half mad baronet, half beautiful woman". However, there has been

credible speculation for many years that Eden's father was actually the

politician and man of letters George Wyndham, whom he resembled in appearance and speech, and with whom his mother was rumoured to have had an affair. Eden had an elder brother called Timothy and a younger brother, Nicholas, who was killed when the battlecruiser HMS Indefatigable blew up and sank at the Battle of Jutland in 1916. Eden was educated at two independent schools: at Sandroyd School from 1907 – 1910, at the time based in Cobham in Surrey (and now the home of Reed's School), followed by Eton College, in Eton in Berkshire, where he won a Divinity prize and excelled at cricket, rugby and rowing, winning House colours in the latter. After the war, he studied at Christ Church at the University of Oxford, where he graduated in Oriental Languages. He was fluent in French, German and Persian, and also spoke Russian and Arabic. During the First World War, Eden served with the 21st (Yeoman Rifles) Battalion of the King's Royal Rifle Corps, and reached the rank of captain. He received a Military Cross, and at the age of twenty-one became the youngest brigade-major in the British Army. At a conference in the early 1930s, he and Adolf Hitler observed that they had probably fought on opposite sides of the trenches in the Ypres sector. After fighting a hopeless seat in the November 1922 General Election, Captain Eden, as he was still known, was elected Member of Parliament for Warwick and Leamington in the December 1923 General Election, as a Conservative. Also in that year he married Beatrice Beckett.

They had two sons (as well as a third who died in infancy), but the

marriage was not a success and later broke up under the strain of a son

missing in action during the latter half of the Second World War. In the 1924 – 1929 Conservative Government, Eden was first Parliamentary Private Secretary to the Home Secretary, Sir William Joynson Hicks, and then in 1926 to the Foreign Secretary Sir Austen Chamberlain. In 1931 he held his first ministerial office as Under Secretary for Foreign Affairs. In 1934 he was appointed Lord Privy Seal and Minister for the League of Nations in Stanley Baldwin's Government. Like many of his generation who had served in the First World War, Eden was strongly anti-war,

and strove to work through the League of Nations to preserve European

peace. However, he was among the first to recognise that peace could

not be maintained by appeasement of Nazi Germany and fascist Italy. He privately opposed the policy of the Foreign Secretary, Sir Samuel Hoare, of trying to appease Italy during its invasion of Abyssinia (Ethiopia) in 1935. When Hoare resigned after the failure of the Hoare-Laval Pact, Eden succeeded him as Foreign Secretary. At this stage in his career Eden was considered as something of a leader of fashion. He regularly wore a Homburg hat (similar to a trilby but more rigid), which became known in Britain as an "Anthony Eden". Eden became Foreign Secretary at a time when Britain was having to adjust its foreign policy to face the rise of the fascist powers. He supported the policy of non-interference in the Spanish Civil War, and supported prime minister Neville Chamberlain in

his efforts to preserve peace through reasonable concessions to

Germany. He did not protest when Britain and France failed to oppose Hitler's reoccupation of the Rhineland in

1936. When the French requested a meeting with a view to some kind of

military action in response to Hitler's occupation, Eden in a statement firmly ruled out any military assistance to France. His resignation in February 1938 was largely attributed to growing dissatisfaction with Chamberlain`s policy of Appeasement.

That is, however, disputed by new research; it was not the question if

there should be negotiations with Italy, but only when they should

start and how far they should be carried. Similarly,

he at no point registered his dissatisfaction with the appeasement

policy directed towards Nazi Germany in his period as Foreign

Secretary. He became a Conservative dissenter leading a group

conservative whip David Margesson called the "Glamour Boys," and a leading anti-appeaser like Winston Churchill, who led a similar group called "The Old Guard." Although Churchill claimed to have lost sleep the night of Eden's resignation (later recounted in his wartime memoirs (The Gathering Storm,

1948), they were not allies, and did not see eye to eye until Churchill

became Prime Minister. There was much speculation that Eden would

become a rallying point for all the disparate opponents of Neville

Chamberlain, but instead he maintained a low profile, avoiding

confrontation, though he opposed the Munich Agreement and

abstained in the vote on it in the House of Commons. As a result,

Eden's position declined heavily amongst politicians, though he

remained popular in the country at large; in later years he was often

wrongly supposed to have resigned in protest at the Munich Agreement. In September 1939, on the outbreak of war, Eden, who had briefly rejoined the army with the rank of major, returned to Chamberlain's government as Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs, but was not in the War Cabinet.

As a result, he was not a candidate for the Premiership when

Chamberlain resigned after Germany invaded France in May 1940 and

Churchill became Prime Minister. Churchill appointed Eden Secretary of State for War. At the end of 1940 Eden returned to the Foreign Office, and in this role became a member of the executive committee of the Political Warfare Executive in

1941. Although he was one of Churchill's closest confidants, his role

in wartime was restricted because Churchill conducted the most

important negotiations, with Franklin D. Roosevelt and Joseph Stalin,

himself, but Eden served loyally as Churchill's lieutenant.

Nevertheless he was in charge of handling much of the relations between

Britain and de Gaulle during the last years of the war. Eden was often critical of the emphasis Churchill put on the Special Relationship with the United States, and was often disappointed by American treatment of their British allies. In 1942 Eden was given the additional job of Leader of the House of Commons.

He was considered for various other major jobs during and after the

war, including Commander-in-Chief Middle East in 1942 (this would have

been a very unusual appointment as Eden was a civilian; General Harold Alexander was in fact appointed), Viceroy of India in 1943 (General Archibald Wavell was

appointed to this job), or Secretary-General of the newly-formed United

Nations Organisation in 1945. In 1943 with the revelation of the Katyn Massacre Eden refused to help the Polish Government in Exile. In 1944 Eden went to Moscow to negotiate with the Soviet Union at the Tolstoy Conference. Eden also opposed the Morgenthau Plan to deindustrialise Germany. After the Stalag Luft III murders he

vowed in the House of Commons to bring the perpetrators of the crime to

"exemplary justice", leading to a successful manhunt after the war by

the Royal Air Force Special Investigation Branch. Eden's eldest son, Pilot Officer Simon Gascoigne Eden, went missing in action, later declared deceased, while serving as a navigator with the RAF in Burma, in June 1945. There

was a close bond between Anthony and Simon, and Simon's death was a

great personal shock to his father, who nevertheless accepted it. Lady

Eden reportedly reacted differently to her son's loss, and this led to

a breakdown in the marriage. De Gaulle wrote him a personal letter of condolence in French. In 1945, he was mentioned by Halvdan Koht among seven candidates that were qualified for the Nobel Prize in Peace. However, he did not explicitly nominate any of them. The person actually nominated was Cordell Hull. After the Labour Party won the 1945 elections, Eden went into opposition as Deputy Leader of

the Conservative Party. Many felt that Churchill should have retired

and allowed Eden to become party leader, but Churchill refused to

consider this, and Eden was too loyal to press him. He was in any case

depressed during this period by the break-up of his first marriage and

the death of his eldest son. Churchill was in many ways only "part-time

Leader of the Opposition", given

his many journeys abroad and his literary work, and left the

day-to-day-work largely to Eden. Eden was largely regarded as lacking

sense of party politics and contact with the common man. In these opposition years, however, he developed some knowledge about domestic affairs and created the idea of a "property owning democracy", which Thatcher government's attempted to achieve decades later. His domestic agenda is overall considered centre-left. Anthony Eden is the great-great-grandnephew of author Emily Eden and wrote an introduction to her 1860 novel The Semi-Detached Couple in 1947.

In

1951, the Conservatives returned to office and Eden became Foreign

Secretary for a third time. Churchill was largely a figurehead in this

government, and Eden had an effective control of British foreign policy

for the first time, as the Empire declined and the Cold War grew more intense. He dealt effectively with the various crises of the period, although Britain was no longer the world power it had been before the war. The success of the 1954 Geneva Conference on Indo-China ranks as his outstanding achievement of his third term in the Foreign Office.

During the summer and fall of 1954, the Anglo-Egyptian agreement to

withdraw all British forces from Egypt was also negotiated and

ratified. In 1950 he and Beatrice Eden were finally divorced, and in

1952 he married Churchill's niece, Clarissa Spencer-Churchill (b. 1920), a nominal Roman Catholic who was fiercely criticised by Catholic writer Evelyn Waugh for marrying a divorced man. This second marriage was much more successful than his first had been. In 1954 he was made a Knight of the Garter and became Sir Anthony Eden. Upon regaining office, Winston Churchill and Eden moved for the release of the German war criminals still in British custody, following a policy focused on Anti-Communism and the emerging Cold War. This policy had been discreetly pursued since at least 1947, when Churchill and Harold Alexander had pressured Clement Attlee to commute the death sentence on the German Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, which had been handed down by a British Military Court in Venice on 6 May 1947. Kesselring had been called to account for atrocities perpetrated in Italy during the Second World War, such as the massacre of more than 1,400 innocent civilians in a series of violent reprisals, including the Ardeatine massacre. In

December 1951 Eden introduced to the Cabinet a cleverly drafted policy,

according to which pre-trial custody should be counted against

sentences inflicted upon war criminals, effectively reducing them. The

policy, which apparently aimed only to promote an equitable principle,

exploited a loophole which in certain instances was effectively used to

double a prison reduction already in effect, as for example, in the

case of the German Field Marshal Erich von Manstein. Von

Manstein was mainly accused of orders equating Partisans to Jews, thus

aiming at their indiscriminate extermination. Churchill donated money

to von Manstein's defence, and openly branded the trial against the

German Field Marshal as yet another effort by the then ruling Attlee

government to appease the Soviets. Anticipating

an extensive interpretation of the pre-trial custody reduction, the

Tribunal that condemned von Manstein on 19 December 1949 explicitly

stated in its ruling that "The period during which the accused has been in custody has been taken into account".

Nevertheless, Eden pushed ahead with the idea that it was legitimate to

subtract the pre-trial custody time from the period decreed by judicial

decision even in cases such as von Manstein's. The

pressure on Eden and the government to resolve the war criminals issue

as quickly as possible increased during the summer of 1952, coinciding

with the looming question of the ratification of the European Defence

Community Treaty by West Germany. A lobby that included Harold Alexander (then Minister of Defence) and Basil Liddell Hart strove to this end, echoing the calls in the same direction coming from the German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer,

and the press campaign orchestrated in West Germany for the pardoning

of most war criminals. Alexander in particular had gone to considerable

lengths to justify their release in one way or another, tactically and

falsely emphasising health issues and, almost incredibly, the

"melancholy" experienced by jailed war criminals. Under Eden, who as Foreign Minister had taken over responsibility after the withdrawal of the British High Commission from the International Military Tribunal,

with the clear approval of Churchill, and based on the tactics

suggested by Alexander, which included adequately priming prison

doctors of which medical aspects to emphasise, both Kesselring (July)

and Manstein (August) were released from prison under medical pretexts

during the summer of 1952, allegedly because they needed urgent

hospitalisation for treating, respectively, an "exploratory operation"

on a throat cancer, and cataracts. Following their operations, both

were conveniently left in liberty for an indefinite convalescence

period, and were not to set foot again in jail. Ivone Kirkpatrick swiftly

suggested that Adenauer proposed the application of the same principal

to the US High Commission, which helped West Germany not to

misunderstand the real significance of the "medical" release of the

Field Marshals, and the policy pursued by both the British and the US

governments. However,

to make the path taken by the British government towards the war

criminals clear to German public opinion, a more explicit gesture was

deemed to be necessary. Therefore, on 24 October 1952 Eden signed an

act of clemency in favour of the German Field Marshal Albert Kesselring.

Kesselring, who was pardoned in consideration of his allegedly

cancerous throat, addressed a rally of veterans immediately after his

release, calling for the wholesale liberation of all war criminals. Afterwards

Kesselring lived an active public life for another eight years, mostly

rallying far right veterans as leader of the organisation Stahlhelm, Bund der Frontsoldaten, a post to which he had been elected while still in prison. Thus

Eden, albeit with some reluctance and attention for legal stricture,

had put his signature upon a policy commenced by Churchill which, by

means of a broad campaign of rehabilitation of German military

personalities, was aimed at re-establishing a strong army in what was

then West Germany, as a central part of the NATO front line at the height of Cold War. When

Churchill took over the Foreign Office because of Eden's serious health

problems in 1953, the plan for liberating the war criminals was brought

to its logical conclusion. Selwyn Lloyd, the Minister of State in the Foreign Office with responsibility for German Affairs, was given carte-blanche to

resolve the issue of war criminals, now seen as no more than

embarrassing. On 6 May 1953 Manstein was pardoned, and in 1956 he

returned to service upon Adenauer's call, assuming an important

official role in the resurrection of the German Army. In

April 1955 Churchill finally retired, and Eden succeeded him as Prime

Minister. He was a very popular figure, as a result of his long wartime

service and his famous good looks and charm. His famous words "Peace

comes first, always" added to his already substantial popularity. On taking office he immediately called a general election,

at which the Conservatives were returned with an increased majority.

But Eden had never held a domestic portfolio and had little experience

in economic matters. He left these areas to his lieutenants such as Rab Butler, and concentrated largely on foreign policy, forming a close relationship with U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower. The alliance with the US proved not universal, however, when in July 1956 Gamal Abdel Nasser, President of Egypt, unexpectedly nationalised the Suez Canal, following the Anglo-American withdrawal to fund the Aswan Dam. Eden, in conjunction with France, decided Nasser should be removed from power. The

canal had been built in the 19th century by the Suez Canal Company

through a concession from the viceroy of Egypt, but later became owned

by its British and French shareholders. Eden, drawing on his experience in the 1930s, saw Nasser as another Mussolini,

considering the two men aggressive nationalist socialists determined to

invade other countries. Eden even responded by plotting to assassinate

Nasser by enlisting Miles Copeland's

assistance, since he was apparently a close friend of Nasser's. Others

believed that Nasser was acting from legitimate patriotic concerns and

the nationalisation was determined by the Foreign Office to be legal. In

October 1956, after months of negotiation and attempts at mediation had

failed to dissuade Nasser, Britain and France, in conjunction with Israel, invaded Egypt and occupied the Suez Canal Zone. But Eisenhower was an advocate of decolonisation,

and he immediately and strongly opposed the invasion. Eden, who faced

domestic pressure from his party to take action, as well as stopping the decline of British influence in the Middle East, had

ignored Britain's financial dependence on the U.S. in the wake of the

Second World War, and had overestimated US loyalty towards its closest

ally. Eden was finally forced to bow to American pressure and

increasing hostility at home, to withdraw. At the 'Law not War' rally in Trafalgar Square on 4 November 1956, Eden was ridiculed by Aneurin Bevan:

'Sir Anthony Eden has been pretending that he is now invading Egypt in

order to strengthen the United Nations. Every burglar of course could

say the same thing, he could argue that he was entering the house in

order to train the police. So, if Sir Anthony Eden is sincere in what

he is saying, and he may be, he may be, then if he is sincere in what

he is saying then he is too stupid to be a prime minister'. The Suez Crisis is

widely taken as marking the end of Britain's status as a superpower,

although, in reality, this had happened by the end of the Second World

War. The Suez fiasco ruined, in many eyes, Eden's reputation for statesmanship and led to a breakdown in his health. He went on vacation to Ian Fleming's estate on Jamaica in

November 1956, at a time when he was still determined to soldier on as

Prime Minister. His health, however, did not improve and during his

absence from London, his Chancellor Harold Macmillan and Rab Butler worked to manoeuvre him out of office. Eden resigned on 9 January 1957.

Macmillan, despite having himself been one of the architects of Suez,

succeeded him as Prime Minister in January 1957. Eden retained some of

his personal popularity and was made Earl of Avon in 1961.

In 1986, Eden's official biographer Robert Rhodes James re-evaluated sympathetically Eden's stance over Suez and in 1990, following the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, James asked: "Who can now claim that Eden was wrong?". Such

arguments turn mostly on whether, as a matter of policy, the Suez

operation was fundamentally flawed or whether, as such "revisionists"

thought, the lack of American support conveyed the impression that the

West was divided and weak. Anthony Nutting, who resigned as a Foreign Office Minister over Suez, expressed the former view in 1967, the year of the Arab-Israeli Six-Day War, when he wrote that "we had sown the wind of bitterness and we were to reap the whirlwind of revenge and rebellion". Conversely, D.R. Thorpe,

another of Eden's biographers, suggests that had the Suez venture

succeeded, "there would almost certainly have been no Middle East war

in 1967, and probably no Yom Kippur War in 1973 also". According to Eden's widow, the then US President Dwight D. Eisenhower subsequently regretted his hostile stance over Suez, as apparently did former Secretary of State John Foster Dulles on his deathbed.

A medical mishap would change the course of Eden’s life forever. During an operation in 1953 to remove gallstones, Eden's bile duct was damaged, making him susceptible to recurrent infections, biliary

obstruction and liver failure. He required major surgery on three

occasions to alleviate the problem. Eden was also prescribed Benzedrine, the wonder drug of the 1950s. Regarded by doctors in the 1950s as a harmless stimulant, it belongs to the family of drugs called amphetamines. During this time amphetamines were prescribed and used in a very casual way. Among the side effects of Benzedrine are Insomnia,

restlessness and mood swings, all of which Eden actually suffered

during the Suez Crisis. His drug use is now commonly agreed to have

been a part of the reason for the Prime Minister's ill judgment.

British Government cabinet papers from September 1956, during Eden's term as Prime Minister, have shown that French Prime Minister Guy Mollet approached the British Government suggesting the idea of an economic and political union between France and Great Britain. This was a similar offer, in reverse, to that made by Churchill (drawing on a plan devised by Leo Amery) in June 1940. The offer by Guy Mollet was referred to by Sir John Colville, Churchill's former private secretary, in his collected diaries, The Fringes of Power (1985), his having gleaned the information in 1957 from Air Chief Marshal Sir William Dickson during an air flight (and, according to Colville, after several whiskies and soda). Mollet's request for Union with Britain was rejected by Eden, but the additional possibility of France joining the British Commonwealth was considered, although similarly rejected. Colville noted, in respect of Suez, that Eden and his Foreign Secretary Selwyn Lloyd "felt still more beholden to the French on account of this offer". Eden soon retired and lived quietly with his second wife Clarissa, formerly Clarissa Spencer-Churchill, niece of Sir Winston, in 'Rose Bower' by the banks of the River Ebble in Broad Chalke, Wiltshire. He published a highly acclaimed personal memoir, Another World (1976), as well as several volumes of political memoirs, in which he, however,

denied that there had been any collusion with France and Israel. In his

view, American Secretary of State John Foster Dulles,

whom he particularly disliked, was responsible for the ill fate of the

Suez adventure. This lack of candour further diminished his standing

and a principal concern in his later years was trying to rebuild his

reputation that was severely damaged by Suez, sometimes taking legal

action to protect his viewpoint. It

was not until some years after his death that a more balanced view of

Suez came to be advanced by some historians and other commentators in

the light of subsequent events. Eden sat for extensive interviews for the famed multi-part Thames Television production, The World at War, which was first broadcast in 1973. He also featured frequently in Marcel Ophüls' 1969 documentary Le chagrin et la pitié, discussing the occupation of France in a wider geopolitical context. He spoke impeccable, if accented, French. From 1945 to 1973, Eden was Chancellor of the University of Birmingham, England. On a trip to the United States in 1976 – 1977 to spend Christmas and New Year with Averell and Pamela Harriman, his health rapidly deteriorated. At his family's request, James Callaghan arranged for an RAF plane that was already in America to divert to Miami to fly him home. The Earl of Avon died from liver cancer in Salisbury on

14 January 1977, at the age of 79. Born in the year of Queen Victoria's

Diamond Jubilee, he thus died in the year of Queen Elizabeth II's

Silver Jubilee. Anthony Eden is buried in the country churchyard at Alvediston, just three miles upstream from 'Rose Bower' at the source of the River Ebble. Eden's papers are housed at the University of Birmingham Special Collections. Eden's surviving son, Nicholas Eden (1930 – 1985), known as Viscount Eden until 1977, was also a politician and a minister in the Thatcher government until his premature death from AIDS at the age of 54. Anthony

Eden always made a particularly cultured appearance, well-mannered and

good-looking. This gave him huge popular support throughout his

political life, but some contemporaries felt that he was merely a

superficial person lacking any deeper convictions. That view was

enforced by his very pragmatic approach to politics. Sir Oswald Mosley, for example, said that he never understood why Eden was so strongly pushed by the Tory party, while he felt that Eden's abilities were very much inferior to those of Harold Macmillan and Oliver Stanley. Also, Secretary of State Dean Acheson regarded him as a quite old-fashioned amateur in politics typical of the British Establishment. However,

recent biographies put more emphasis on Eden's achievements in foreign

policy, and perceive him to have held deep convictions regarding world

peace and security as well as a strong social conscience. Eden was for all his abilities not a very effective public speaker. Too often in his career, for instance in the late 1930s, following his resignation from Chamberlain's government, his parliamentary performances disappointed many of his followers. Churchill once even commented on an Eden speech that the latter had used every cliché except "God is love". His

inability to express himself clearly is often attributed to shyness and

lack of self-confidence. Eden is known to have been much more direct in

meeting with his secretaries and advisors than in Cabinet meetings and public speeches, sometimes tending to become enraged and behaving "like a child", only to regain his temper within a few minutes.