<Back to Index>

- Physician Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran, 1845

- Painter Joseph Marie Vien, 1716

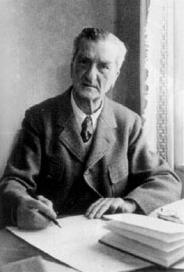

- Regent of Hungary Miklós Horthy de Nagybánya, 1868

PAGE SPONSOR

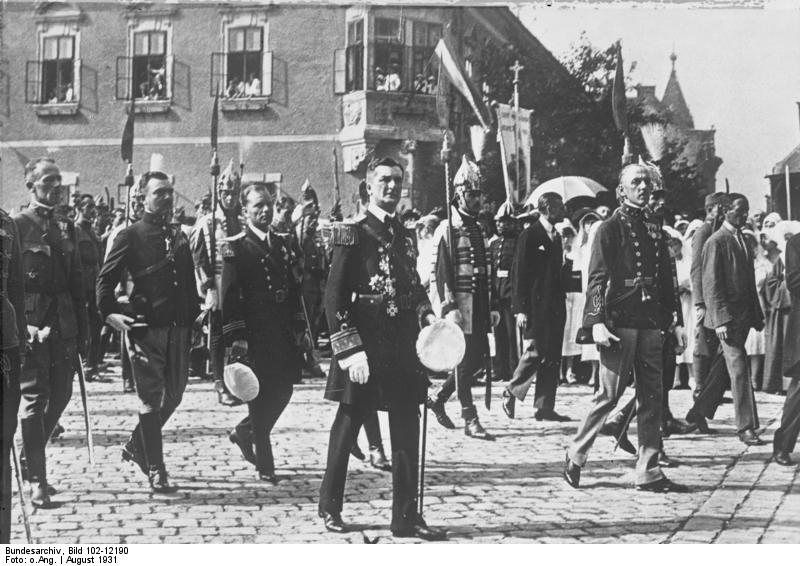

Nicholas Horthy de Nagybánya (Hungarian: Vitéz nagybányai Horthy Miklós, German: Nikolaus von Horthy und Nagybánya; Kenderes, 18 June 1868 – 9 February 1957, Estoril) was the Regent of the Kingdom of Hungary during the interwar years and throughout most of World War II, serving from 1 March 1920 to 15 October 1944. Horthy was styled "His Serene Highness the Regent of the Kingdom of Hungary" (Hungarian: Ő Főméltósága a Magyar Királyság Kormányzója).

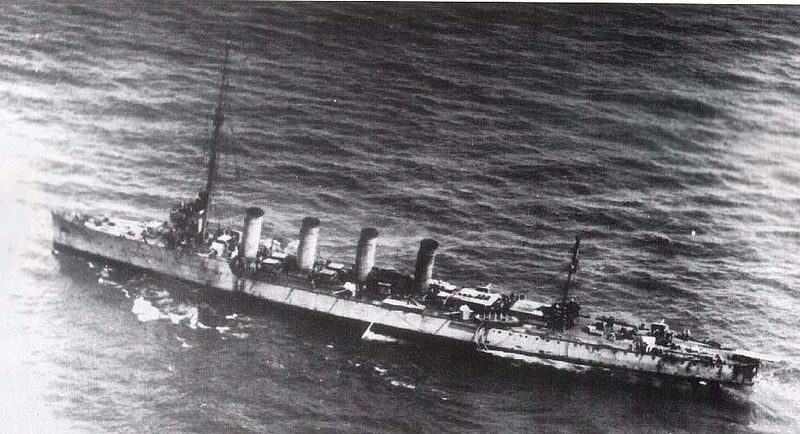

Admiral Horthy was an officer of the Austro-Hungarian Navy. He served in the Otranto Raid and at the Battle of the Strait of Otranto (1917), and was its commander-in-chief in the last year of the First World War. After Hungarian socialists and communists under Béla Kun seized power in Hungary in 1919 and proclaimed the Hungarian Soviet Republic, a counterrevolutionary government formed and asked Horthy to take command of its forces. With the consent of the Allied powers, Romanian forces invaded Hungary and overthrew Kun's government. When

the Romanians evacuated Budapest in November, 1919, Horthy entered at

the head of the National Army. The Hungarian Communist Party was

banned, and in 1920 Horthy was declared Regent and Head of State, a position he held until his deposition in October 1944. A conservative who

was distinctly inclined toward the right of the political spectrum, he

guided Hungary through the years between the two world wars, and into

an alliance with Nazi Germany, in exchange for the restoration of some

of the Hungarian territories lost by the Treaty of Trianon. In April 1941, Hungary entered World War II as

an ally of Germany. But Horthy's faltering allegiance to his German

patron eventually led the Nazis to invade and take control of the

country with Operation Margarethe in March 1944. In October 1944, Horthy announced that Hungary would surrender and withdraw from the Axis.

He was forced to resign, placed under arrest and taken to Bavaria; at

war's end he came under the custody of U.S. troops. After appearing as

a witness at the Nuremberg war-crimes trials in 1948, Horthy settled and lived out his remaining years in Portugal. His memoirs, Ein Leben für Ungarn, were published in German in 1953, and an English translation appeared three years later. Miklós Horthy came from an old Calvinist noble family, making him one of the few openly Protestant politicians

in a mostly Catholic country. Horthy entered the Austro-Hungarian naval

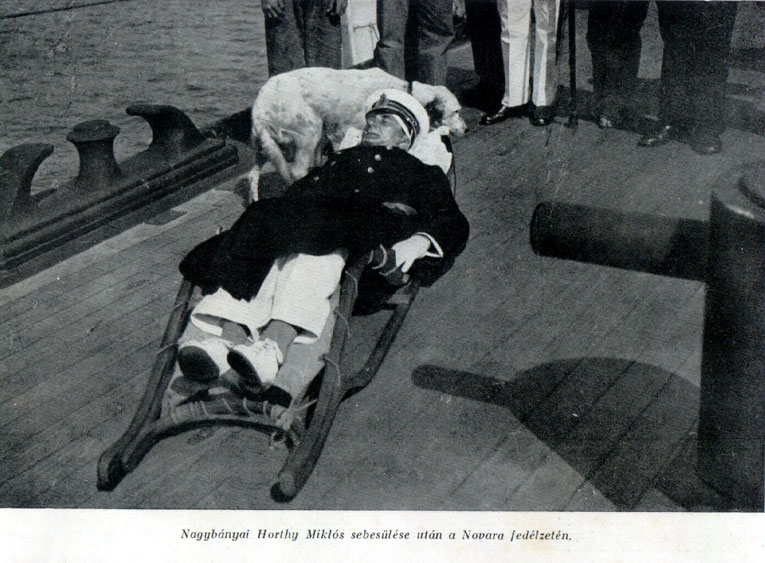

academy at Fiume (now Rijeka, Croatia) at age 14. As a young man, Horthy traveled around the world and served as a diplomat for the Austro-Hungarian Empire in Turkey and other countries. From 1908 until 1914 he was an aide-de-camp to Emperor Franz Joseph, for whom he had a great respect. During World War I, Horthy distinguished himself first as a captain and later as an admiral in the Austro-Hungarian Navy. During the war he defeated the Italian Navy several times, and was wounded at the battle of the Otranto Straits. Due

to his success on behalf of the Dual Monarchy, he was promoted to

Commander in Chief of the Imperial Fleet in March, 1918, and held that

position until he was ordered by Emperor Charles to surrender the fleet to the new State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs on 31 October. The

end of the war saw Hungary turned into a landlocked nation, and hence

the new government had little need for Horthy's services. He retired

with his family to his private estate at Kenderes, but his role as a Hungarian leader was far from over. Two national traumas immediately following the First World War profoundly shaped the spirit and future of the Hungarian nation. The first was the loss, as dictated by the Entente powers,

of large portions of Hungarian territory that had bordered other

countries. These were lands which had been Hungary's as part of the

Austro-Hungarian Empire, they were carved away by the Allies and ceded

to the nations of Czechoslovakia, Romania, Austria and Yugoslavia. The excisions, eventually ratified in the Treaty of Trianon at

Versailles, cost Hungary two-thirds of its territory and one-third of

its native Hungarian speakers, and dealt the population a terrible

psychological blow. The second trauma in some sense sprang from the

first: in March 1919, after the first proto-democratic efforts at

government in Hungary faltered, Communist Béla Kun seized power in the capital of Budapest. Kun and his colleagues proclaimed the Hungarian Soviet Republic,

and promised the restoration of Hungary's former grandeur. Instead, his

efforts at reconquest failed, and Hungarians were treated to a

Soviet-style repression in the form of armed gangs who intimidated or murdered enemies of the regime. This period of violence came to be known as the Red Terror.

Tibor Szamuely, a close collaborator of Bela Kun, even boasted that,

"Terror is the principal weapon of our regime." Figures vary, but one

generally accepted number of victims of the Red Terror is around 500

killed. Within

weeks of his coup, Kun's popularity plummeted. On 30 May 1919,

anti-Communist politicians formed a counter-revolutionary government in

the southern city of Szeged, occupied by French forces at the time. There, Gyula Károlyi asked

former admiral Horthy, still considered a war hero, to be the Minister

of War in the new government and take command of a

counter-revolutionary force which would be named the National Army (Hungarian: Nemzeti Hadsereg). Horthy consented, and arrived in Szeged on June 6. Soon after, because of orders from the Entente,

the cabinet was reformed, and Horthy was not given a seat in it.

Undaunted, Horthy managed to retain control of the National Army by

detaching the Army command from the War ministry. On 6 August French-supported Romanian forces entered Budapest. The Communist government collapsed and its leaders fled. In retaliation for the Red Terror, reactionary crews now exacted revenge in a two-year wave of violent repression known today as the White Terror. These reprisals - which almost certainly exceeded the Red Terror in

scope and cruelty - were organized and carried out by officers of Horthy's National Army, particularly Pál Prónay Gyula Ostenburg-Moravek and Iván Héjjas.

Their victims were primarily Communists, Social Democrats, peasants,

and Jews. Most Hungarian Jews were not supporters of the Bolsheviks,

but much of the leadership of the Hungarian Soviet Republic had been young Jewish intellectuals, and anger about the Communist revolution easily translated into anti-Semitic hostility. Precisely

how much Horthy knew or approved of the White Terror is not known.

Biographer Thomas Sakmyster writes simply that Horthy "tacitly

supported the right wing officer detachments" who carried out these

atrocities. Horthy

himself declined to apologize for the savagery of his officer

detachments, writing later: "I have no reason to gloss over deeds of

injustice and atrocities committed when an iron broom alone could sweep

the country clean." And

he endorsed Edgar von Schmidt-Pauli's poetic justification of the White

reprisals ("Hell let loose on earth cannot be subdued by the beating of

angels' wings") remarking, "the Communists in Hungary, willing

disciples of the Russian Bolshvists, had indeed let hell loose." This

deep hostility toward Communism would be the more lasting legacy of

Kun's abortive revolution: a conviction shared by Horthy and his

country's ruling elite that would help drive Hungary into a fatal

alliance with Adolf Hitler. The

Romanian army retreated from Budapest on November 14, leaving Horthy to

enter the city, where in a fiery speech he reminded the capital's

citizens that they had betrayed Hungary by their Communist lapses: "... The nation of the Hungarians loved and admired Budapest,

which became its polluter in the last years. Here, on the banks of the

Danube, I arraign her. This city has disowned her thousand years of

tradition, she has dragged the Holy Crown and the national colours in

the dust, she has clothed herself in red rags. The finest of the nation

she threw into dungeons or drove into exile. She laid in ruin our

property and wasted our wealth. Yet the nearer we approached to this

city, the more rapidly did the ice in our hearts melt. We are now ready

to forgive her." Following the orders of the Entente, Romanian troops finally evacuated Hungary on 25 February 1920. On 1 March 1920, the National Assembly of Hungary re-established the Kingdom of Hungary, but chose not to recall the deposed King Charles IV (Karoly IV of Hungary) from exile as the return of the Habsburg Emperor on the Hungarian throne was unacceptable to the Entente powers.

Instead, with National Army officers controlling the parliament

building, the assembly voted to install Horthy as head of state; he

defeated Count Albert Apponyi by a vote of 131 to 7. Bishop Ottokár Prohászka then

led a small delegation to meet Horthy, announcing, “Hungary’s

Parliament has elected you Regent! Would it please you to accept the

office of Regent of Hungary?” To their astonishment, Horthy declined

unless his powers were expanded. As Horthy stalled, the politicians

folded, and granted him "the general prerogatives of the King, with the

exception of the right to name titles of nobility and of the patronage

of the Church." Those

prerogatives included the power to appoint and dismiss prime ministers,

to convene and dissolve parliament, and to command the armed forces.

With those sweeping powers guaranteed, Horthy took the oath of office. (Carl I did try to regain his throne twice.) Among

20th-century heads of state, Horthy’s role was unique. His official

position is usually referred to as “Regent,” but his Hungarian title is

better translated as "Royal Governor" or "Protector." The Hungarian

state was legally a kingdom, but it had no king, and sought none (the

Entente powers would not likely have allowed it). The national

government actually took the form of a parliamentary republic, with a prime minister at its head. Thus Horthy was a constitutional figurehead, but he was by no means a toothless one. He

ruled, but he did not govern; he wrote no laws, but had powerful

influence over his country’s destiny by means of his constitutional

powers, his prestige and the loyalty of his ministers to the crown. His

regal bearing, military reputation and devotion to Hungary lent him a

royal authority as the country edged out of its Imperial past towards a

modern democracy. A

Hungarian joke sums it up: for the next 24 years, Hungary would be a

kingdom without a king, ruled by an admiral without a fleet, in a

country without a coastline. The

first decade of Horthy’s reign was primarily consumed by stabilizing

the Hungarian political system and economy. Horthy’s chief partner in

these efforts was his prime minister, István Bethlen. Bethlen

sought to stabilize the economy while building alliances with stronger

nations which could advance Hungary’s cause. That cause was, primarily,

reversing the losses of the Treaty of Trianon.

The humiliations of Trianon continued to occupy the central place in

Hungarian foreign policy, and in the popular imagination; the indignant

anti-Trianon slogan “Nem, nem soha!” (“No, no never!”) became a

ubiquitous motto of Hungarian outrage. When in 1927 the British

newspaper magnate Lord Rothermere denounced, in the pages of his Daily Mail, the partitions ratified at Trianon, an official letter of gratitude was eagerly signed by 1.2 million Hungarians. But Hungary’s stability was precarious, and the Great Depression derailed much of Bethlen’s economic balance. Horthy replaced him with an old reactionary confederate from his Szeged days: Gyula Gömbös.

Gömbös was an outspoken anti-Semite and a budding fascist.

And although he agreed to Horthy’s demands that he temper his

anti-Jewish rhetoric and work amicably with Hungary’s large Jewish

professional class, Gömbös’s tenure began swinging Hungary’s

political mood powerfully rightward. He strengthened Hungary’s ties to Benito Mussolini’s Italian fascist state. And most fatefully, when Adolf Hitler took power in Germany in 1933, he found in Gömbös an admiring and obliging colleague. Gömbös

rescued the failing economy by securing trade guarantees from Germany –

a strategy which positioned Germany as Hungary’s primary trading

partner and tied Hungary’s future even more tightly to Hitler’s. He

also assured Hitler that Hungary would quickly become a one-party state

modeled on the Nazi party control of Germany. Gömbös died in

1936, before he realized his most extreme goals, but he left his nation

headed into firm partnership with the German dictator. Hungary

now entered into an intricate dance of influence with Hitler's regime,

and Horthy began to play a greater and more public role in navigating

Hungary along this dangerous path. For

Horthy, Hitler served as a bulwark against Soviet encroachment or

invasion. Horthy was, in the eyes of observers, obsessed with the

Communist threat. One American diplomat remarked that Horthy's

anti-Communist tirades were so common and ferocious that diplomats

"discounted it as a phobia." Horthy

clearly saw his country as trapped between two stronger powers, both of

them dangerous; evidently he considered Hitler to be the more

manageable of the two. Hitler was also able to wield great influence

over Hungary not only as the country’s major trading partner; he also

fed several of Horthy’s key ambitions: Maintaining Hungarian

sovereignty and satisfying the national hunger to reclaim former

Hungarian lands. Horthy’s strategy was one of cautious, sometimes even

grudging, alliance. How the regent granted or resisted Hitler's

demands, especially with regard to Hungarian military action and the

treatment of Hungary's Jews, remains the central topic by which his

career has been judged. Horthy's

relationship with Hitler was, by his own account, a tense one – largely

due, he said, to his unwillingness to bend his nation's policies to the

German dictator's desires. On a state visit by Horthy to Germany in

August 1938, Hitler asked Horthy for troops and materiel to participate

in Germany's planned invasion of Czechoslovakia. In exchange, Horthy

later reported, "He gave me to understand that as a reward we should be

allowed to keep the territory we had invaded." Horthy said he declined, insisting to Hitler that Hungary's claims on the disputed lands should be settled by peaceful means. Three months later, after the Munich Agreement put control of southern Czechoslovakia in Hitler's hands, Hitler allowed Hungary to annex nearly one-third of Slovakia.

Horthy enthusiastically rode into the re-acquired territory (which was

predominantly populated by Hungarians) at the head of his troops,

greeted by emotional ethnic Hungarians: "As I passed along the roads,

people embraced one another, fell upon their knees, and wept with joy

because liberation had come to them at last, without war, without

bloodshed." But

as "peaceful" as this annexation was, and as just as it may have seemed

to many Hungarians, it was a dividend of Hitler's brinksmanship and

threats of war, in which Hungary was now inextricably complicit. Hungary

was now committed to the Axis agenda: on 24 February 1939, it joined

the Anti-Comintern pact, and on April 11 withdrew from the League of

Nations. American journalists began to refer to Hungary as "the jackal

of Europe." This combination of menace and reward fixed Hungary firmly as a Nazi client state. In March 1939, when Hitler took what remained of Czechoslovakia by force, Hungary was allowed to annex Carpathian Ruthenia from the First Slovak Republic as well during the Slovak-Hungarian War. In August 1940, Hitler intervened on Hungary's behalf once again, taking Northern Transylvania away from Romania, and awarding it to Hungary. (Second Vienna Award). But

in spite of their cooperation with the Nazi regime, Horthy and his

government would be better described as "conservative authoritarian"

than "fascist". Certainly Horthy was as hostile to the home-grown

fascist and ultra-nationalist movements which flourished in Hungary

between the wars (particularly the Arrow Cross Party) as he was to Communism. The Arrow Cross leader, Ferenc Szálasi, was repeatedly imprisoned at Horthy's command. John F. Montgomery,

who served in Budapest as U.S. ambassador from 1933 to 1941, openly

admired this side of Horthy’s character and reported the following

incident in his memoir: in March 1939, Arrow Cross supporters disrupted

a performance at the Budapest opera house by

chanting “Justice for Szálasi!” loud enough for the regent to

hear. A fight broke out, and when Montgomery went to take a closer

look, he discovered that And

yet, by the time of this episode, Horthy had allowed his government to

give in to Nazi demands that the Hungarians enact laws restricting the

lives of the country's Jews. The first Hungarian anti-Jewish Law, in

1938, limited the number of Jews in the professions, the government and

commerce to twenty percent, and the second reduced it to five percent

the following year; 250,000 Hungarian Jews lost their jobs as a result.

A "Third Jewish Law" of August 1941 prohibited Jews from marrying

non-Jews, and defined anyone having two Jewish grandparents as

"racially Jewish." A Jewish man who had non-marital sex with a "decent

non-Jewish woman resident in Hungary" could be sentenced to three years

in prison. Horthy's

personal views on Jews and their role in Hungarian society are the

subject of some debate. In an October 1940 letter to prime minister Pál Teleki,

Horthy echoed a widespread national sentiment: that Jews enjoyed too

much success in commerce, the professions, and industry - success which

needed to be curtailed: Nevertheless,

as the war years progressed, Horthy proved to be more protective of

Hungary's Jews than many of his political colleagues, and much more so

than his political rivals. In this light, his insistence that he was an

"anti-Semite" may have been an effort to give himself political cover

against the attacks from the extreme antisemitic elements of Hungarian

politics. The Kingdom of Hungary was gradually drawn into the war itself. In 1939 and 1940, volunteer units fought in Finland's Winter War. In April 1941, Hungary became, in effect, a member of the Axis. Hungary permitted Hitler to send troops across Hungarian territory for the invasion of Yugoslavia and ultimately sent its own troops to claim its share of the dismembered Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Prime Minister Pál Teleki, horrified that he had failed to prevent this collusion with the Nazis against a former ally, committed suicide. In

June 1941, the Hungarian government finally yielded to Hitler's demands

that the nation contribute to the Axis war effort. On 27 June, Hungary

became part of Operation Barbarossa and declared war on the Soviet Union.

The Hungarians sent in troops and materiel only four days after Hitler

began his invasion of the Soviet Union. Eighteen months later, more

poorly equipped and less motivated than their German allies, the

200,000 troops of the Hungarian Second Army ended up holding the front on the Don River west of Stalingrad. The

first massacre of Jewish people from Hungarian territory took place in

August 1941, when government officials ordered the deportation of Jews

without Hungarian citizenship (principally refugees from other

Nazi-occupied countries) to Ukraine. Roughly 18,000 - 20,000 of these deportees were slaughtered by Friedrich Jeckeln and his SS troops; only 2,000 - 3,000 survived. These killings are known as the Kamianets - Podilskyi Massacre.

This event, in which the slaughter of Jews numbered for the first time

in the tens of thousands, is considered the first large scale massacre

of the Holocaust. Because of the objections of Hungary's leadership, the deportations were halted. By

early 1942, Horthy was already seeking to put some distance between

himself and Hitler's regime. That March, he dismissed the pro-German prime minister László Bárdossy, and replaced him with Miklós Kállay, a moderate whom Horthy expected to loosen Hungary's ties to Germany. In September 1942, personal tragedy struck the Hungarian Regent. 37-year-old István Horthy,

Horthy's eldest son, was killed. István Horthy was the Deputy

Regent of Hungary and a Flight Lieutenant in the reserves, 1/1 Fighter

Squadron of the Royal Hungarian Air Force. He was killed when his Hawk (Héja) fighter crashed at an air field near Ilovskoye. Then,

in January 1943, Hungary's enthusiasm for the war effort, never

especially high, suffered a tremendous blow. The Soviet army, in the full momentum of its triumphant turnaround after the Battle of Stalingrad, punched through Romanian troops at a bend in the Don River and

virtually obliterated the Second Hungarian Army in a few days'

fighting. In this single action, Hungarian combat fatalities jumped by

80,000. Jew and non-Jew suffered together in this defeat, as Hungary's

troops were accompanied by some 40,000 Jews and political undesirables

in forced-labor units. German

officials blamed Hungary's Jews for the nation's "defeatist attitude."

In the wake of the Don Bend disaster, Hitler demanded at an April 1943

meeting that Horthy take sterner measures against the 800,000 Jews

still living in Hungary. Horthy and his government supplied 10,000

Jewish deportees for labor battalions, but otherwise refused to comply.

Cautiously, the Hungarian government began to explore contacts with the

Western Allies in hopes of negotiating a surrender. Just before the deportations began, two Slovakian Jewish prisoners, Rudolf Vrba and Alfréd Wetzler,

escaped from Auschwitz and passed details of what was happening inside

the camps to officials in Slovakia. This document, known as the Vrba-Wetzler Report,

was quickly translated into German and passed among Jewish groups and

then to Allied officials. Details from the report were broadcast by the BBC on 15 June and printed in The New York Times on 20 June. World leaders, including Pope Pius XII (June 25), President Franklin D. Roosevelt on June 26, and King Gustaf V of Sweden on 30 June, subsequently

pleaded with Horthy to use his influence to stop the deportations.

Roosevelt specifically threatened military retaliation if the

transports were not ceased. On July 2, Allied bombers executed the

heaviest bombings inflicted on Hungary during the war. Hungarian radio

accused Jews of guiding the bombers to their targets with radio

transmissions and light signals, but on 7 July Horthy at last ordered

the transports halted. By that time, 437,000 Jews had been sent to Auschwitz, most of them to their deaths. Horthy was informed about the number of the deported Jews some days later: "approximately 400,000". By many estimates, one of every three people murdered at Auschwitz was a Hungarian Jew killed between May and July 1944. There

remains some uncertainty over how much Horthy could have known about

the number of Hungarian Jews being deported, their destination, and

their intended fate - and when he knew it as well as what he could have

done about it. Some historians have argued that Horthy believed that

the Jews were being sent to the camps to work, and that they would be returned to Hungary after the war. Horthy

himself could not have been clearer in his memoirs: "Not before

August," he wrote, "did secret information reach me of the horrible

truth about the extermination camps." But the Vrba-Wetzler statement is

believed to have been passed to Hungarian Zionist Rudolf Kasztner no

later than 28 April 1944, and according to Holocaust historian Yehuda

Bauer, Kasztner passed it on to contacts who gave it to both Horthy's

son and daughter-in-law by mid-May, when the deportations were about to

begin. It

is often argued that Hungary's "relatively mild" anti-Jewish Laws,

which were passed under German pressure, appeased the Nazis enough to

create a relatively safe environment for the Jews before the 1944

German invasion. It seems certain that the survival of 124,000 Hungarian Jews in Budapest until

the arrival of the Soviets would have been impossible without Horthy’s

years of foot-dragging reluctance to implement German orders. On 15 July 1944 Anne McCormick, a foreign correspondent for The New York Times wrote

in defense of Hungary as the last refuge of Jews in Europe, declaring

that “as long as they exercised any authority in their own house, the

Hungarians tried to protect the Jews.” In

August 1944, the Nazis were distracted by their failing war effort, and

Romania withdrew from the Axis and turned on Hitler and his allies. In

Budapest, Horthy moved to reconsolidate his influence: he dismissed the

Nazi-friendly ministers installed in the Spring, and began considering

strategies for surrendering to the Allied force he deeply distrusted:

the Red Army. Working through his trustworthy General Béla Miklós who

was in contact with Soviet forces in eastern Hungary, Regent Horthy

sought to surrender to the Soviets while preserving the Hungarian

government's autonomy. The Soviets willingly promised this, and on

October 11 Horthy and the Soviets finally agreed to surrender terms. On

15 October 1944, Horthy told his government ministers that Hungary had

signed an armistice with the Soviet Union. "It is clear today that

Germany has lost the war... Hungary has accordingly concluded a

preliminary armistice with Russia, and will cease all hostilities

against her." Horthy

"...informed a representative of the German Reich that we were about to

conclude a military armistice with our former enemies and to cease all

hostilities against them." The Nazis had anticipated Horthy's move. On the 15th, Hitler initiated Operation Panzerfaust, sending commando Otto Skorzeny to Budapest with instructions to remove Horthy from power. Horthy's son Miklós Horthy, Jr.,

was meeting with Soviet representatives to finalize the surrender when

Skorzeny and his troops forced their way into the meeting and kidnapped

Miklós at gunpoint. Trussed up in a carpet, Miklós was

immediately driven to the airport and flown to Germany to serve as a

hostage. Skorzeny then brazenly led a convoy of German troops and four Tiger II tanks to the Vienna Gates of Castle Hill,

where the Hungarians had been ordered not to resist. Though one unit

had not received the order, the Germans quickly captured Castle Hill

with minimal bloodshed: only seven soldiers were killed and twenty-six

wounded. Horthy was captured by Edmund Veesenmayer and

his staff later on the 15th and taken to the Waffen SS office, where he

was held overnight. With his son's life in the balance, the Regent

consented to sign a document officially abdicating his office, and

placing Ferenc Szálasi and the fascist Arrow Cross in

control of the country. Horthy understood that the Germans merely

wanted the stamp of his prestige on a Nazi-sponsored Arrow Cross

coup — but he signed anyway. As he later explained his capitulation: "I

neither resigned nor appointed Szálasi Premier, I merely

exchanged my signature for my son’s life. A signature wrung from a man

at machine-gun point can have little legality." Horthy

met Skorzeny three days later at Pfeffer-Wildenbruch's apartment and

was told he would be transported to Germany in his own special train.

Skorzeny told Horthy that he would be a "guest of honor" in a secure

Bavarian castle. On October 17, Horthy was personally escorted by

Skorzeny into captivity at Schloss Hirschberg in Bavaria, where he was guarded closely, but allowed to live in comfort. With the help of the SS, the Arrow Cross Party leadership

moved swiftly to take command of the Hungarian armed forces, and to

prevent the surrender that Horthy had arranged. The Arrow Cross swiftly

resumed persecution of Jews and other undesirables. In the three months

between November 1944 and January 1945, death squads of the Arrow Cross Party shot 10,000 to 15,000 Jews on the banks of the Danube. The Arrow Cross also welcomed Eichmann back

to Budapest, where he began the deportation of the city's surviving

Jews (Eichmann never successfully completed this phase of his plans,

thwarted in large measure by the efforts of Swedish diplomat Raul Wallenberg. Out of a pre-war Hungarian Jewish population estimated at 825,000, only 260,000 survived. By

December 1944, Budapest was under siege by Soviet forces. The Arrow

Cross leadership retreated across the Danube into the hills of Buda in

late January, and by February the city surrendered to the Soviet

liberator. Horthy

remained under house arrest in Bavaria until the war in Europe ended.

On April 29, his SS guardians fled in the face of the Allied advance.

On May 1, Horthy was first liberated, and then arrested, by elements of

the U.S. 7th Army. After his arrest, Horthy was moved between a variety of detention locations before finally arriving at the prison facility at Nuremberg in late September 1945. There he was asked to provide evidence to the International Military Tribunal in

preparation for the trial of the Nazi leadership. Although he was

interviewed repeatedly about his contacts with some of the defendants,

he did not testify in person. In Nuremberg he was reunited with his

son, Miklos. Horthy

went out of his way to record in his memoirs every indignity suffered

at American hands, but gradually he came to believe that his arrest had

been arranged and choreographed by the Americans in order to protect

him from Communist retributive urges. Indeed, the former regent

reported being told that Josip Tito, the new ruler of Yugoslavia, asked that Horthy be charged with complicity with the 1942 massacre of Serbian and Jewish civilians by Hungarian troops in the Bačka region of Vojvodina. Serbian historian Zvonimir Golubović has claimed that Horthy was aware of these raids, and approved their being carried out. But

American trial officials declined to present charges against Horthy, a

kindness that may have been the result of the influence in Washington

of Horthy's admirer, the former ambassador John Montgomery. According to the memoirs of Ferenc Nagy,

who served for a year as prime minister in post-war Hungary, the

Hungarian Communist leadership was also interested in extraditing

Horthy for trial. Nagy said that Joseph Stalin was

more forgiving: that Stalin told Nagy during a diplomatic meeting in

April 1945, "not to judge Horthy. After all, he is an old man now, and

it should not be forgotten that he offered armistice in the Fall of

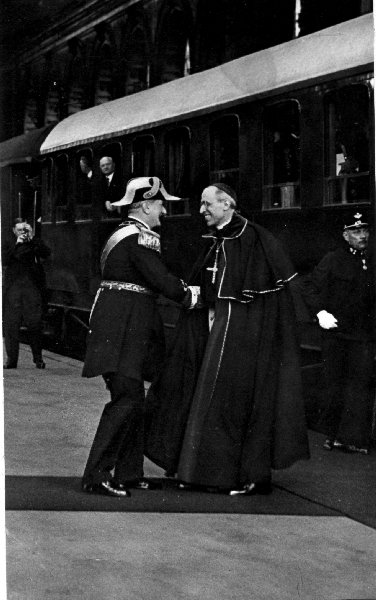

1944." On 17 December 1945, Horthy was released from Nuremberg prison and allowed to rejoin his family in the German town of Weilheim, in Bavaria. The Horthys lived there for four years, supported financially by ambassador John Montgomery, his successor, Herbert Pell, and by Pope Pius XII, whom he knew personally. In March 1948, Horthy returned to testify at the Ministries Trial, the last of the twelve U.S.-run Nuremberg Trials; he testified against Edmund Veesenmayer, the Nazi administrator who had controlled Hungary during the deportations to Auschwitz in the Spring of 1944. Veesenmayer was sentenced to 20 years imprisonment, but was released in 1951. For

Horthy, returning to Budapest was impossible; Hungary was now firmly in

the hands of a Soviet-led Communist government. In an extraordinary

twist of fate, the chief of Hungary's post-war Communist apparatus was Mátyás Rákosi,

one of Béla Kun's colleagues from the ill-fated Communist coup

of 1919. Kun had been executed during Stalin's purges of the late

1930s, but Rákosi had survived in a Hungarian prison cell; in

1940 Horthy had permitted Rákosi to emigrate to the Soviet Union

in exchange for a series of highly symbolic Hungarian battle flags from

the 19th century, which were in Russian hands. Thus,

after allying his nation with Hitler in part to keep Communism at bay,

Horthy had to watch helplessly from abroad as Moscow installed one of

the 1919 revolutionaries to run Hungary. In

1949, the Horthy family secured permission to emigrate to Portugal,

thanks to Miklós Jr.’s contacts with Portuguese diplomats in

Switzerland. Horthy and members of his family were relocated to the

seaside town of Estoril.

Once again, Horthy's old friend, John Montgomery, came to the

ex-regent's rescue. Montgomery recruited a small group of wealthy

Hungarians to support the Horthy family's life in exile. According to

Horthy's daughter-in-law, this group included Jewish industrialist

Ferenc Chorin and lawyer László Pathy, also Jewish. In exile, Horthy wrote his memoirs, Ein Leben für Ungarn (English: A Life for Hungary),

published under the name of Nikolaus von Horthy, in which he narrated

many personal experiences from his youth until the end of World War II.

He claimed that he had distrusted Hitler for much of the time he knew

him and tried to perform the best actions and appoint the best

officials in his country. He also highlighted Hungary's alleged

mistreatment by many other countries since the end of World War I.

Horthy was one of the few Axis heads of state to survive the war, and

thus to write post-war memoirs. He

never lost his deep contempt for Communism, and in his memoirs he

blamed Hungary's alliance with the Axis on the threat posed by the

"Asiatic barbarians" of the Soviet Union. He railed against the

influence that the Allies' victory had given to Stalin's totalitarian

state. "I feel no urge to say 'I told you so,' " Horthy wrote, "nor to

express bitterness at the experiences that have been forced upon me.

Rather, I feel wonder and amazement at the vagaries of humanity." He died in 1957. Horthy was married once, to Magdolna Purgly de Jószáshely. He had two sons, Miklós Horthy, Jr. (often rendered in English as "Nicholas" or "Nikolaus") and István Horthy,

who served as his political assistants; and two daughters, Magda and

Paula. Of his four children, only Miklós outlived him. According to footnotes in his memoirs, Horthy was very distraught about the failure of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956.

In his will, Horthy asked that his body not be returned to Hungary

"until the last Russian soldier has left." His heirs honored the

request. In 1993, two years after the Soviet troops left Hungary,

Horthy's body was returned to Hungary and he was buried in his home

town of Kenderes. The reburial in Hungary was the subject of some controversy in the country.

“ "...two

or three men were on the floor and he [Horthy] had another by the

throat, slapping his face and shouting what I learned afterward was:

"So you would betray your country, would you?" The Regent was alone,

but he had the situation in hand.... The whole incident was typical not

only of the Regent's deep hatred of alien doctrine, but of the kind of

man he is. Although he was around seventy two years of age, it did not

occur to him to ask for help; he went right ahead like a skipper with a

mutiny on his hands." ” “ "As

regards the Jewish problem, I have been an anti-Semite throughout my

life. I have never had contact with Jews. I have considered it

intolerable that here in Hungary everything, every factory, bank, large

fortune, business, theater, press, commerce, etc. should be in Jewish

hands, and that the Jew should be the image reflected of Hungary,

especially abroad. Since, however, one of the most important tasks of

the government is to raise the standard of living, i.e., we have to

acquire wealth, it is impossible, in a year or two, to eliminate the

Jews, who have everything in their hands, and to replace them with

incompetent, unworthy, mostly big-mouthed elements, for we should

become bankrupt. This requires a generation at least." ”

By 1944, the Axis was losing the war, and the Red Army stood at Hungary's borders. Aware of the regent's intentions to surrender, Hitler summoned him to a conference in Klessheim (today in Austria).

He pressured Horthy to make greater contributions to the war effort,

and again commanded him to deal more harshly with Hungary's Jews.

Horthy conceded that Germany could deport a large number of Jewish

laborers (the generally accepted figure is 100,000) to German

factories, but refused to give further ground. The conference was a ruse. As Horthy was returning home on 19 March the Wehrmacht invaded and occupied Hungary. Horthy was permitted to remain the nation's regent, but power was in fact placed in the hands of Edmund Veesenmayer, Hitler's plenipotentiary in Budapest. The Nazis forced Horthy to appoint an acquiescent prime minister, Döme Sztójay, whose government eagerly proceeded to participate in the final spasms of the Holocaust. The chief agents of this collaboration were Andor Jaross, the Minister of the Interior, and his two rabidly anti-Semitic state secretaries, László Endre and László Baky (later

to be known as the "Deportation Trio"). On April 9, Prime Minister

Sztójay and the Germans obligated Hungary to place 300,000

Jewish laborers at the disposal of the Reich. Five days later, on 14

April Endre, Baky, and SS Colonel Adolf Eichmann began

to deport all Hungarian Jews. The Yellow Star and Ghettoization laws,

and deportation were accomplished in less than 8 weeks with the

enthusiastic help of the new Hungarian government and the authorities,

particularly the gendarmerie (csendőrség). The deportation of Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz began on 15 May 1944 and continued at a rate of 12,000 a day until 9 July.