<Back to Index>

- Paleontologist Othenio Abel, 1875

- Painter Léon Joseph Florentin Bonnat, 1833

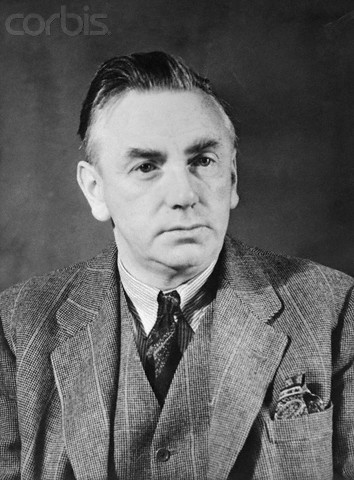

- 2nd Taoiseach of the Republic of Ireland John Aloysius Costello, 1891

PAGE SPONSOR

John Aloysius Costello (Irish: Seán Alabhaois Mac Coisdealbha; 20 June 1891 – 5 January 1976), a successful barrister, was one of the main legal advisors to the government of the Irish Free State after independence, Attorney General of Ireland from 1926 – 1932 and Taoiseach from 1948 – 1951 and 1954 – 1957.

John A. Costello was born on 20 June 1891, in Dublin.

Educated at St Josephs Christian Brothers School in Fairview, North

Dublin, where future taoiseach Charles Haughey later attended, and at University College Dublin, he graduated with a degree in modern languages and law. He studied at King's Inns to

become a barrister, winning the Victoria Prize there in 1913 and 1914.

Costello was called to the bar in 1914 and practised as a barrister

until 1922 In 1922 Costello joined the staff of the Attorney General in the newly established Irish Free State. Three years later he was called to the inner bar and the following year, 1926, he became Attorney-General to the Cumann na nGaedhael government, led by W.T. Cosgrave. While serving in this position he represented Ireland at Imperial Conferences and League of Nations meetings. He was also elected a Bencher of the Honourable Society of King's Inns. Costello lost his position as Attorney-General when Fianna Fáil came to power in 1932. The following year, however, he was elected to Dáil Éireann as a Cumann na nGaedhael (later Fine Gael) TD. During the Dáil debate on the Emergency Powers Act 1939 Costello

was highly critical of the delegation of powers, stating that "… we are

asked not merely to give a blank cheque, but, to give an uncrossed

cheque to the Government." He

lost his seat at the general election of 1943, but regained it when de

Valera called a snap election in 1944. From 1944 to 1948 he was Fine

Gael's front-bench spokesman on External Affairs. In

1948 Fianna Fáil had been in power for sixteen consecutive years

and had been blamed for a downturn in the economy following World War II. The general election results

showed Fianna Fáil still the largest party, with twice as many

seats as the nearest party, Fine Gael. While it looked as if Fianna

Fáil were heading for a seventh consecutive victory all the

other parties in the Dáil joined to form the first inter-party government in the history of the Irish state. The coalition consisted of Fine Gael, the Labour Party, the National Labour Party, Clann na Poblachta, Clann na Talmhan and

several Independent TDs. While it looked as if co-operation between

these parties would not be feasible a shared opposition to Fianna

Fáil and Éamon de Valera overcame all other difficulties and the coalition government was formed.

Since

Fine Gael was the largest party in the government it had the task of

providing a suitable candidate for Taoiseach. Naturally it was assumed

that its leader, Richard Mulcahy, would be offered the post. However, he was an unacceptable choice to Clann na Poblachta and its deeply republican leader, Seán MacBride. This was due to Mulcahy's record during the Civil War.

Instead, Mulcahy stepped aside and allowed Costello to become

Taoiseach. Costello, who had never held a ministerial position and who

had not sought the leadership was now the leader of a complex

government. Much of its success would depend on his leadership skills During the campaign Clann na Poblachta had promised to repeal the External Relations Act of 1936, but did not make an issue of this when the government was being formed. However, Costello and his Tánaiste, William Norton of

the Labour Party, also disliked the Act. During the summer of 1948 the

Cabinet discussed repealing the Act; however, no firm decision was made. In September 1948 Costello was on an official visit to Canada when a reporter asked him about the possibility of leaving the British Commonwealth. Costello, for the first time, declared publicly that the Irish government was indeed going to repeal the Act and declare a republic. It has been suggested that this was a reaction to offence caused by the Governor-General of Canada, Harold Alexander,

1st Earl Alexander of Tunis, who was of Northern Irish descent and who

allegedly arranged to have placed symbols of Northern Ireland, notably

a replica of the famous Roaring Meg cannon used in the Siege of Derry,

in front of Costello at a state dinner. What is certain is that an

agreement about toasts to both the King (symbolising Canada) and the

President (representing Ireland) was broken and only a toast to the

King was offered, to the fury of the Irish delegation. The news took the British Government,

and even some of Costello's ministers, by surprise. The former had not

been consulted, and following the declaration of the republic in 1948,

the UK passed the Ireland Act in 1949. This guaranteed the position of Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom while

at the same time granting certain rights to citizens of the Republic

living in the United Kingdom. Ireland left the Commonwealth on 18 April

1949 when the Republic of Ireland Act 1948 came into force. Many nationalists now saw partition as the last obstacle on the road to total national independence. In 1950 the independent minded Minister for Health, Dr. Noel Browne, introduced the Mother and Child Scheme.

The scheme would provide mothers with free maternity treatment and

their children with free medical care up to the age of sixteen.

However, the bill was opposed by doctors, who feared a loss of income,

and Roman Catholic bishops,

who feared the scheme could lead to birth control and abortion. The

Cabinet was divided over the issue, many feeling that the state could

not afford such a scheme. Costello and others in the Cabinet made it

clear that in the face of such opposition they would not support the

minister. Browne resigned from the government on 11 April 1951, and the

scheme was dropped. He immediately published his correspondence with

Costello and the bishops, something which had hitherto not been done.

Ironically derivatives of the Mother and Child Scheme would be

introduced in acts of 1954, 1957 and 1970.

The Costello Government had a number of noteworthy achievements. A new record was set in house-building, the Industrial Development Authority and

Córas Tráchtála were established, and the Minister

for Health, Noel Browne, brought about a spectacular advance in the

treatment of tuberculosis. Ireland also joined a number of

organisations such as the Organisation for European Economic

Co-Operation and the Council of Europe. However, the government refused

to join NATO while

the British remained in Northern Ireland. The scheme to supply

electricity to even the remotest parts of Ireland was also accelerated. While

the "Mother and Child" incident did destabilise the government to some

extent, it did not lead to its collapse as is generally thought. The

government continued; however, prices were rising, a balance of

payments crisis was looming, and two TDs withdrew their support for the

government. These incidents added to the pressure on Costello and so he

decided to call a general election for

June of 1951. The result was inconclusive but Fianna Fáil

returned to power. Costello resigned as Taoiseach. It was at this

election that Costello's son, Declan, was elected to the Dáil. Over

the next three years while Fianna Fáil was in power a

dual-leadership role of Fine Gael was taking place. While Richard

Mulcahy was the leader of the party, Costello, who had proved his skill

as Taoiseach, remained as parliamentary leader of the party. In the general election in

June 1954 Fianna Fáil lost power. A campaign dominated by

economic issues resulted in a Fine Gael - Labour Party - Clann na Talmhan

government coming to power. Costello was once again elected Taoiseach.

Unfortunately the government could do little to change the ailing

nature of Ireland's economy, with emigration and unemployment remaining

high. Costello's government did have some success with Ireland becoming a member of the United Nations in 1955. Although the government had a comfortable majority and seemed set for a full term in office, a resumption of IRA activity in Northern Ireland and Britain caused internal strains. The government took strong action against the republicans. In spite of supporting the government from the backbenches, Seán MacBride, the leader of Clann na Poblachta, tabled a motion of no confidence, based on the weakening state of the economy. Fianna Fáil also

tabled its own motion of no confidence, and, rather than face almost

certain defeat, Costello again asked President Seán T. O'Kelly to dissolve the Oireachtas. The general election which followed in 1957 gave Fianna Fáil an overall majority and

started another sixteen years of unbroken rule for the party. Following the defeat Costello returned to the bar. In 1959, when Richard Mulcahy resigned the leadership of Fine Gael to James Dillon, Costello retired to the backbenches. He remained on as a TD until 1969 when he retired from politics, being succeeded by Garret FitzGerald as Fine Gael TD for Dublin South East. During his career he was presented with a number of awards from many universities in the United States. He was also a member of the Royal Irish Academy from

1948. In March 1975 he was made a freeman of the city of Dublin, along

with his old political opponent Éamon de Valera. He practised at

the bar up to a short time before his death in Dublin on 5 January

1976, at the age of 84.