<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Jørgen Pedersen Gram, 1850

- Author Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, 1838

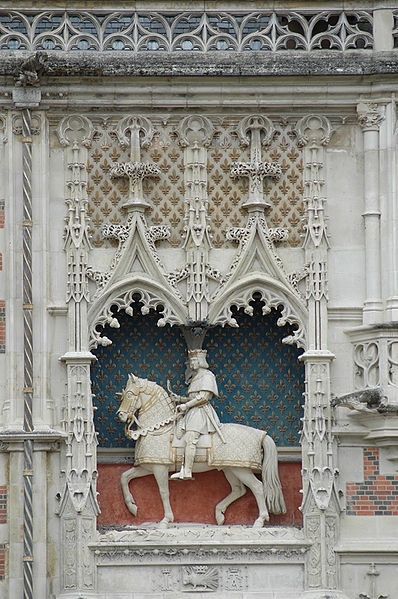

- King of France Louis XII, 1462

PAGE SPONSOR

Louis XII (27 June 1462 – 1 January 1515), called "the Father of the People" (French: Le Père du Peuple), was king of France and the sole monarch from the Valois-Orléans branch of the House of Valois. He reigned from 1498 to 1515 and pursued a very active foreign policy.

Louis was born on 27 June 1462, in the Château de Blois, Blois, Touraine (in the contemporary Loir-et-Cher département). The son of Charles, duc d'Orléans and Marie of Cleves, he succeeded his father as Duke of Orléans in the year 1465.

In the 1480s Louis was involved in the so-called Mad War against royal authority. Allied with Francis II, Duke of Brittany, he confronted the royal army at the Battle of Saint-Aubin-du-Cormier, but was comprehensively defeated and captured. Pardoned three years later, Louis joined his cousin King Charles VIII, in campaigns in Italy.

All four of Charles VIII's children died in infancy. The French interpretation of the Salic Law permitted claims to the French throne only by male agnatic descendants of French kings. This made Louis, the great-grandson of King Charles V, the most senior claimant as heir of Charles VIII. Louis thus succeeded to the throne on the king's death. Although

he came late (and unexpectedly) to power, Louis acted with vigour,

reforming the French legal system, reducing taxes and improving

government, much like his contemporary Henry VII did in England. He was also skilled in managing his nobility, including the powerful Bourbon faction, which greatly contributed to the stability of French government. In the Ordinance of Blois of 1499 and the Ordinance of Lyon of 1510, he extended the powers of royal judges and made efforts to curb corruption in the law. Highly complex French customary law was to be codified and ratified by royal proclamation. In an attempt to take control of the Duchy of Milan, to which he had a claim in right of his paternal grandmother Valentina Visconti, Louis embarked on several campaigns in Italy. In the Italian War of 1499 – 1504, he successfully secured Milan itself in the year 1499 from his enemy, Ludovico Sforza, and it remained a French stronghold for twelve years. His greatest success came in his war with Venice, with the victory at the Battle of Agnadello in 1509. Things became much more difficult for him from 1510 onwards, especially after Julius II, the great warrior Pope, took control of the Vatican and formed the "Holy League" to oppose the ambitions of the French in Italy. The French were eventually driven from Milan by the Swiss in the year 1513. Louis also pursued the claim of his immediate predecessor to the Kingdom of Naples with Ferdinand II, the King of Aragon from the House of Trastámara. They agreed to partition the Neapolitan realm in the Treaty of Granada (1500), but were eventually at war over the terms of partition, and by the year 1504 France had lost its share of Naples. Louis's failure to hold on to Naples prompted a commentary by Niccolò Machiavelli in his famous opus The Prince: Kind

Louis was brought into Italy by the ambition of the Venetians, who

expected by his coming to get control of half the state of Lombardy. I don't mean to blame the king for his part in the scheme; he wanted a

foothold in Italy, and not only had no friends in the province, but

found all doors barred against him because of King Charles's behavior.

Hence he had to take what friendships he could get; and if he had made

no further mistakes in his other arrangements, he might have carried

things off very successfully. By taking Lombardy, the king quickly

regained the reputation lost by Charles. Genoa yielded, and the Florentines turned friendly, the Marquis of Mantua, the Duke of Ferrara, the Bentivogli (of Bologna), the countess Forlì, the lords of Faenza, Pesaro, Rimini, Camerino, Piombino, and the people of Lucca, Pisa, and Siena all

sought him out with professions of friendship. At this point the

Venetians began to see the folly of what they had done, since in order

to gain for themselves a couple of districts in Lombardy, they had now

made the king master of a third of Italy. Consider

how easy it would have been for the king to maintain his position in

Italy if he had observed the rules [of not worrying about weaker

powers, decreasing the strength of a major power, not introducing a

very power foreigner in the midst of his new subjects and taking up

residence among his new subjects and/or setting up colonies], and

become the protector and defender of his new friends. They were many,

they were weak, some of them were afraid of the Venetians, others of

the Church, hence they were bound to stick by him; and with their help,

he could easily have protected himself against the remaining great

powers. But no sooner was he established in Milan than he took exactly

the wrong tack, helping Pope Alexander to occupy the Romagna.

And he never realized that by this decision he was weakening himself,

driving away his friends and those who had flocked to him, while

strengthening the Church by adding vast temporal power to the spiritual

power which gives it so much authority. Having made this first mistake,

he was forced into others. To limit the ambition of Alexander and keep

him from becoming master of Tuscany,

he was forced to come to Italy himself [in 1502]. Not satisfied with

having made the Church powerful and deprived himself of his friends, he

went after the kingdom of Naples and divided it with the king of Spain (Ferdinand II).

And where before he alone had been the arbiter of Italy, he brought in

a rival to whom everyone in the kingdom who was ambitious on his own

account or dissatisfied with Louis could have recourse. He could have

left in Naples a caretaker king of his own, but he threw him out, and

substituted a man capable of driving out Louis himself. If

France could have taken Naples with her own power, she should have done

so; if she could not, she should not have split the kingdom with the

Spaniards. The division of Lombardy that she made with the Venetians

was excusable, since it gave Louis a foothold in Italy; the division of

Naples with Spain was an error, since there was no such necessity for

it. [When Louis made the final mistake of] depriving the Venetians of

their power (who never would have let anyone else into Lombardy unless

they were in control), he thus lost Lombardy. In 1476, Louis was required to marry the pious Joan of France (1464 – 1505), the daughter of his second cousin, Louis XI, the middle aged "Spider King" of France. After Louis XII's predecessor Charles VIII died childless, Louis' marriage was annulled in order to allow him to marry Charles’ widow, the former Queen-Consort, Anne of Brittany (1477 – 1514), who was the daughter and heiress of Francis II of Brittany, in a strategy meant to integrate the duchy of Brittany into the French monarchy. The

annulment, described as "one of the seamiest lawsuits of the age", was

not simple, however. Louis did not, as might be expected, argue the

marriage to be void due to consanguinity (the general allowance for the

dissolution of a marriage at that time). Though he could produce witnesses to claim that the two were closely related due

to various linking marriages, there was no documentary proof, merely

the opinions of courtiers. Likewise, Louis could not argue that he had

been below the legalage of consent (fourteen)

to marry: no one was certain when he had been born, with Louis claiming

to have been twelve at the time, and others ranging in their estimates

between eleven and thirteen. As there was no real proof, however, he

was forced to make other arguments. Accordingly,

Louis (much to the horror of his Queen) claimed that she was physically

malformed, providing a rich variety of detail precisely how, and that

he had therefore been unable to consummate the

marriage. Joan, unsurprisingly, fought this uncertain charge fiercely,

producing witnesses to Louis' boast of having "mounted my wife three or

four times during the night." Louis also claimed that his sexual performance had been inhibited by witchcraft; Joan responded by asking how he was able to know what it was like to try to make love to her. Had the Papacy been a neutral party, Joan would likely have won, for Louis's case was exceedingly weak. Unfortunately for the Queen, Pope Alexander VI (the

former Roderic Borja) was committed for political reasons to grant the

divorce, and accordingly he ruled against Joan, granting the annulment.

Outraged, she reluctantly stepped aside, saying that she would pray for

her former husband, and Louis married the equally reluctant former

Queen, Anne.

After the death of Anne, Louis then married Mary Tudor (1496 – 1533), the sister of Henry VIII, the King of England in Abbeville,

France, on 9 October 1514, in an attempt to conceive an heir to his

throne and perhaps to further establish a future claim for his

descendants upon the English throne as well. He was ultimately

unsuccessful. Despite two previous marriages, the king had no living

sons and sought to produce an heir; but Louis died on 1 January 1515,

less than three months after he married Mary, reputedly worn out by his

exertions in the bedchamber. Their union produced no children. Louis died on 1 January 1515, and was interred in Saint Denis Basilica. Due to the tradition of Salic Law, which did not allow women to inherit the throne of France, he was succeeded by his first cousin's son, Francis I (who was also his son-in-law), who founded his own line of French kings.

Louis

proved to be a popular king. At the end of his reign the crown deficit

was no greater than it had been when he succeeded Charles VIII in 1498,

despite several expensive military campaigns in Italy. His fiscal

reforms of 1504 and 1508 tightened and improved procedures for the

collection of taxes. He had duly earned the title of Father of the People ("Le Père du Peuple"), conferred upon him by the Estates in 1506.