<Back to Index>

- Neuroanatomist Franz Joseph Gall, 1758

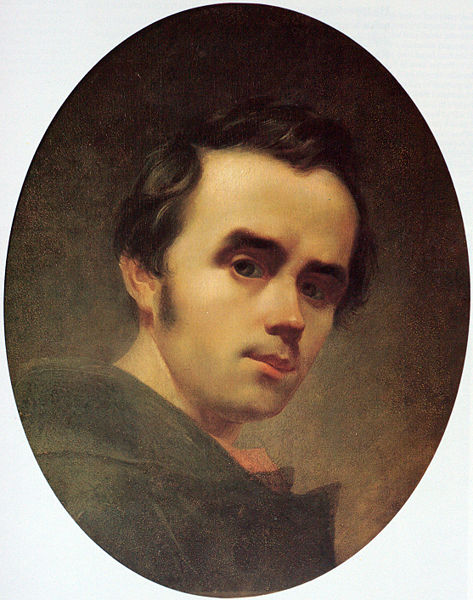

- Poet and Artist Taras Hryhorovych Shevchenko, 1814

- People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov, 1890

PAGE SPONSOR

Taras Hryhorovych Shevchenko (Ukrainian: Тара́с Григо́рович Шевче́нко) (March 9 [O.S. February 25] 1814 – March 10 [O.S. February 26] 1861) was a Ukrainian poet, artist and humanist. His literary heritage is regarded to be the foundation of modern Ukrainian literature and, to a large extent, the modern Ukrainian language. Shevchenko also wrote in Russian and left many masterpieces as a painter and an illustrator.

Born into a serf family in the village of Moryntsi, of Kiev Governorate of the Russian Empire (now in Cherkasy Oblast, Ukraine) Shevchenko was orphaned at the age of eleven. He was taught to read by a village precentor, and loved to draw at every opportunity. Shevchenko went with his Russian aristocrat lord Pavel Engelhardt to Vilna (Vilnius, 1828 – 1831) and then to Saint Petersburg.

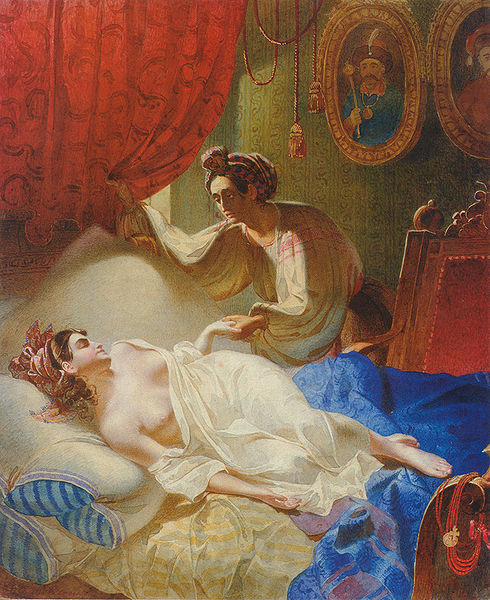

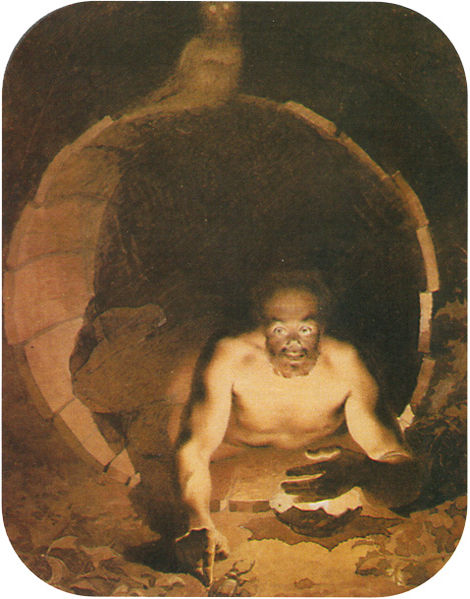

Engelhardt noticed Shevchenko's artistic talent and apprenticed him in Vilna to Jan Rustem, then in Saint Petersburg to Vasiliy Shiriaev for four years. There he met the Ukrainian artist Ivan Soshenko, who introduced him to other compatriots such as Yevhen Hrebinka and Vasyl Hryhorovych, and to the Russian painter Alexey Venetsianov. Through these men Shevchenko also met the famous painter and professor Karl Briullov, who donated his portrait of the Russian poet Vasily Zhukovsky as a lottery prize, whose proceeds were used to buy Shevchenko's freedom on May 5, 1838. In the same year Shevchenko was accepted as a student into the Academy of Arts in the workshop of Karl Briullov. The next year he became a resident student at the Association for the Encouragement of Artists. At the annual examinations at the Imperial Academy of Arts,

Shevchenko was given a Silver Medal for a landscape. In 1840 he again

received the Silver Medal, this time for his first oil painting, The Beggar Boy Giving Bread to a Dog. He began writing poetry while he was a serf and in 1840 his first collection of poetry, Kobzar, was published. Ivan Franko, the renowned Ukrainian poet in the generation after Shevchenko, had this to say of the compilation: "[Kobzar]

immediately revealed, as it were, a new world of poetry. It burst forth

like a spring of clear, cold water, and sparkled with a clarity,

breadth and elegance of artistic expression not previously known in

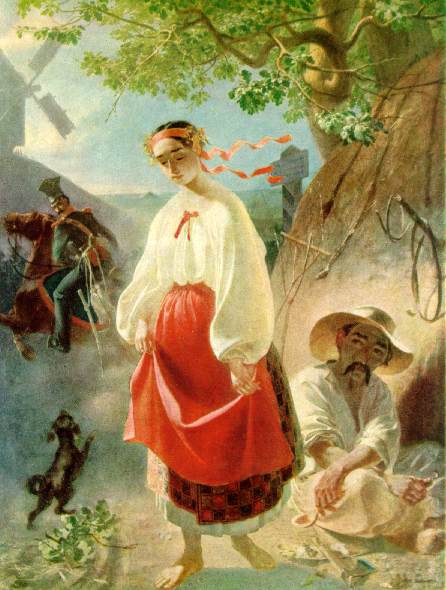

Ukrainian writing". In 1841, the epic poem Haidamaky was released. In September 1841, Shevchenko was awarded his third Silver Medal for The Gypsy Fortune Teller. Shevchenko also wrote plays. In 1842, he released a part of the tragedy Mykyta Hayday and in 1843 he completed the drama Nazar Stodolya. While residing in Saint Petersburg, Shevchenko made three trips to the regions of modern Ukraine,

in 1843, 1845, and 1846. The difficult conditions under which his

countrymen lived had a profound impact on the poet-painter. Shevchenko

visited his still enserfed siblings and other relatives, met with

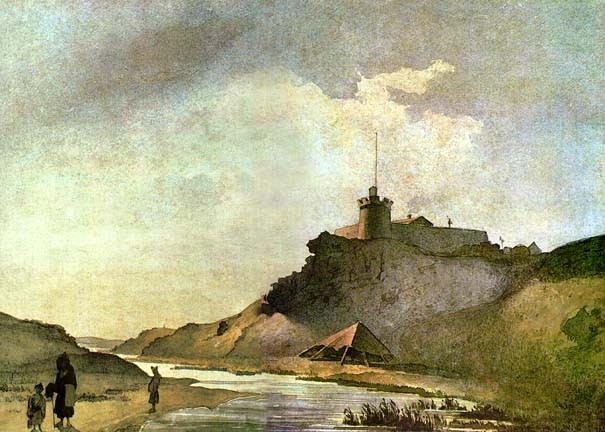

prominent Ukrainian writers and intellectuals such as: Yevhen Hrebinka, Panteleimon Kulish, and Mykhaylo Maksymovych, and was befriended by the princely Repnin family especially Varvara Repnina. In 1844, distressed by the condition of Ukrainian regions in the Russian Empire,

Shevchenko decided to capture some of his homeland's historical ruins

and cultural monuments in an album of etchings, which he called Picturesque Ukraine. On

March 22, 1845, the Council of the Academy of Arts granted Shevchenko

the title of an artist. He again travelled to Ukraine where he met

historian Nikolay Kostomarov and other members of the Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius, a Pan-Slavist political society dedicated to the political liberalization of the Empire and transforming it into a federation-like

polity of Slavic nations. Upon the society's suppression by the

authorities, Shevchenko was arrested along with other members on April

5, 1847. Although he probably was not an official member of the

Brotherhood, during the search his poem "The Dream" ("Son") was found. This poem criticized imperial rule, personally attacked Emperor Nicholas I and his wife Alexandra Feodorovna,

and therefore was considered extremely inflammatory, and of all the

members of the dismantled society Shevchenko was punished most

severely. The Tsar was about to pardon Shevchenko, since literature was

half as bad, as other forms of dissent, which he faced (Decembrist uprising etc.), had it been not for the poem, "The Dream". Vissarion Belinsky wrote

in his memoirs that, Nicholas I, knowing Ukrainian very well, laughed

and chuckled whilst reading the section about himself, but his mood

quickly turned to bitter hatred when he read about his wife. Shevchenko

in a humuliating tone described her physical condition (tic,

which she developed whilst fearing for the safety of her family during

the Decembrist Uprising). After reading this the Tsar firmly stated "Suppose, he had reasons not to be on terms with me, but what has she done to deserve this?" Shevchenko was sent to prison in Saint Petersburg. He was exiled as a private with the Russian military Orenburg garrison at Orsk, near Orenburg, near the Ural Mountains. Tsar Nicholas I, confirming his sentence, added to it, "Under the strictest surveillance, without a right to write or paint." With

the exception of some short periods of his exile, the enforcement of

the Tsar's ban on his creative work was lax. The poet produced several

drawings and sketches as well as writings while serving and traveling

on assignment in the Ural regions and areas on modern Kazakhstan. But

it was not until 1857 that Shevchenko finally returned from exile after

receiving a pardon, though he was not permitted to return to St.

Petersburg but was ordered to Nizhniy Novgorod.

In May 1859, Shevchenko got permission to move to his native Ukraine.

He intended to buy a plot of land not far from the village of Pekariv and settle in Ukraine. In July, he was arrested on a charge of blasphemy, but was released and ordered to return to St. Petersburg. Taras

Shevchenko spent the last years of his life working on new poetry,

paintings, and engravings, as well as editing his older works. But

after his difficult years in exile his final illness proved too much.

Shevchenko died in Saint Petersburg on March 10, 1861, the day after

his 47th birthday. He was first buried at the Smolensk Cemetery in Saint Petersburg. However, fulfilling Shevchenko's wish, expressed in his poem "Testament" ("Zapovit"), to be buried in Ukraine,

his friends arranged to transfer his remains by train to Moscow and

then by horse drawn wagon to his native land. Shevchenko's remains were

buried on May 8 on Chernecha Hill (Monk's Hill; now Taras Hill) by the Dnieper River near Kaniv. A tall mound was erected over his grave, now a memorial part of the Kaniv Museum Preserve. Dogged by terrible misfortune in love and life, the poet died seven days before the Emancipation of Serfs was announced. His works and life are revered by Ukrainians and his impact on Ukrainian literature is immense. Taras Shevchenko has a unique place in Ukrainian cultural history and in world literature. His writings formed the foundation for the modern Ukrainian literature to a degree that he is also considered the founder of the modern written Ukrainian language (although Ivan Kotlyarevsky pioneered

the literary work in what was close to the modern Ukrainian in the end

of the eighteenth century.) Shevchenko's poetry contributed greatly to

the growth of Ukrainian national consciousness, and his influence on

various facets of Ukrainian intellectual, literary, and national life

is still felt to this day. Influenced by Romanticism,

Shevchenko managed to find his own manner of poetic expression that

encompassed themes and ideas germane to Ukraine and his personal vision

of its past and future. In

view of his literary importance, the impact of his artistic work is

often missed, although his contemporaries valued his artistic work no

less, or perhaps even more, than his literary work. A great number of

his pictures, drawings and etchings preserved to this day testify to

his unique artistic talent. He also experimented with photography and

it is little known that Shevchenko may be considered to have pioneered

the art of etching in the Russian Empire (in 1860 he was awarded the title of Academician in the Imperial Academy of Arts specifically for his achievements in etching.) His

influence on Ukrainian culture has been so immense, that even during

Soviet times, the official position was to downplay strong Ukrainian nationalism expressed

in his poetry, suppressing any mention of it, and to put an emphasis on

the social and anti-Tsarist aspects of his legacy, the Class struggle within the Russian Empire. Shevchenko, who himself was born a serf and

suffered tremendously for his political views in opposition to the

established order of the Empire, was presented in the Soviet times as

an internationalist who stood up in general for the plight of the poor

classes exploited by the reactionary political regime rather than the

vocal proponent of the Ukrainian national idea. This

view is significantly revised in modern independent Ukraine, where he

is now viewed as almost an iconic figure with unmatched significance

for the Ukrainian nation, a view that has been mostly shared all along

by the Ukrainian diaspora that has always revered Shevchenko. There are many monuments to Shevchenko throughout Ukraine, most notably at his memorial in Kaniv and in the center of Kiev, just across from the Kiev University that bears his name. The Kiev Metro station, Tarasa Shevchenka, is also dedicated to Shevchenko. Among other notable monuments to the poet located throughout Ukraine are the ones in Kharkiv (in front of the Shevchenko Park), Lviv, Luhansk and many others. Outside

of Ukraine, monuments to Shevchenko have been put up in several

location of the former USSR associated with his legacy, both in the

Soviet and the post-Soviet times. The modern monument in Saint Petersburg was erected on December 22, 2000, but the first monument was built in the city in 1918 on the order of Lenin shortly after the Great Russian Revolution. There is also a monument located next to the Shevchenko museum at the square that bears the poet's name in Orsk, Russia (the location of the military garrison where the poet served) where there are also a street, a library and the Pedagogical Institute named after the poet. There are Shevchenko monuments and museums in the cities of Kazakhstan where he was later transferred by the military: Aqtau (the city was named Shevchenko between 1964 and 1992) and nearby Fort Shevchenko (renamed from Fort Alexandrovsky in 1939). After Ukraine gained its independence in the wake of the 1991 Soviet Collapse, some Ukrainian cities replaced their statues of Lenin with statues of Taras Shevchenko and in some locations that lacked streets named to him, local authorities renamed the streets or squares to Shevchenko. Outside of Ukraine and the former USSR, monuments to Shevchenko have been put up in many countries, usually under the initiative of local Ukrainian diasporas. There are several memorial societies and monuments to him throughout Canada and the United States, most notably a monument in Washington, D.C., near Dupont Circle. There is also a monument in Soyuzivka in New York State, Tipperary Hill in Syracuse, New York, a park is named after him in Elmira Heights, N.Y., and a street is named after him in New York City's East Village. The town of Vita in Manitoba, Canada, was originally named Shevchenko in his honor. There is a Shevchenko Square in Paris located in the heart of the central Saint-Germain-des-Prés district. The Leo Mol sculpture garden in Winnipeg,

Manitoba, Canada, contains many images of Taras Shevchenko. A two-tonne

bronze statue of Shevchenko, located in a memorial park outside of Oakville, Ontario, was

discovered stolen in December 2006. It was taken for scrap metal; the

head was recovered in a damaged state, but the statue was not

repairable. The head is on exhibit at the Taras Shevchenko Museum &

Memorial Park Foundation in Toronto. In 2001, the Ukrainian society "Prosvita" raised the initiative of building a Church near the Chernecha Mount in Kaniv, where Taras Shevchenko is buried. The

initiative got a rather supportive response in the society. Since than

many charity events have been held all over the country to gather

donations for the above purpose. A marathon under the slogan "Let’s

Build a Church for the Kobzar" by the First National Radio Channel of

Ukraine collected 39,000 hryvnias (about US $7,500) in October 2003.