<Back to Index>

- Physician Jean Astruc, 1684

- Painter Alonzo Cano, 1601

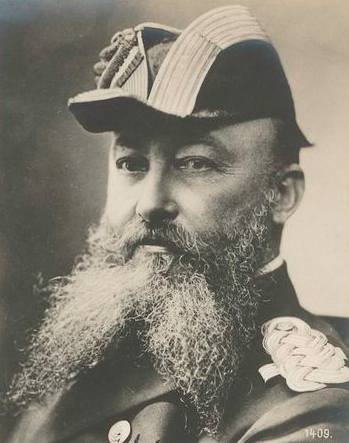

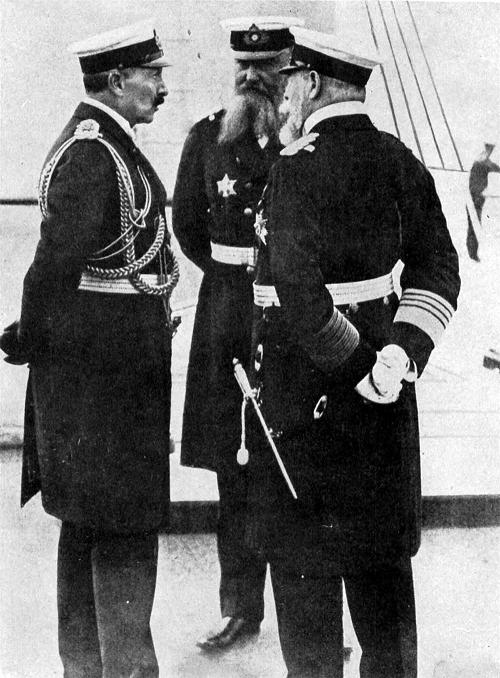

- Secretary of State of the German Imperial Naval Office Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, 1849

PAGE SPONSOR

Alfred von Tirpitz (March 19, 1849 – March 6, 1930) was a German Admiral, Secretary of State of the German Imperial Naval Office, the powerful administrative branch of the Kaiserliche Marine from 1897 until 1916. He is considered to be the founder of the German Imperial navy.

Tirpitz was born in Küstrin in the Prussian province of Brandenburg, the son of lawyer and later judge, Rudolf Tirpitz (1811 - 1905). His mother was the daughter of a doctor. Tirpitz grew up in Frankfurt (Oder). He recorded in his memoirs that he was a mediocre student as a child. Tirpitz spoke English fluently and was sufficiently at home in England that he sent his two daughters to Cheltenham Ladies' College.

On 18 November 1884 he married Maria Augusta Lipke (born 11 October 1860 in Schwetz, West Prussia, died after 1941). On 12 June 1900 he was elevated to the Prussian nobility, becoming von Tirpitz. Tirpitz joined the Prussian Navy more

by accident than design when a friend announced that he was doing so.

Tirpitz decided he liked the idea and with the consent of his parents

became a naval cadet at the age of 16, on 24 April 1865. He attended Kiel Naval School. Within a year Prussia was at war with Austria. Tirpitz became a midshipman (Seekadett) on 24 June 1866 and was posted to a sailing ship patrolling the English Channel. In 1866 Prussia became part of the North German Confederation, the navy officially became that of the confederation and Tirpitz joined the new institution on 24 June 1869. On 22 September 1869 he had obtained the rank of Sub-Lieutenant as (Unterleutnant zur See) and served onboard SMS Konig Wilhelm. During the Franco-Prussian war the

German navy was greatly outnumbered and so the ship spent the duration

of the war at anchor, much to the embarrassment of the navy. During the

early years of Tirpitz' career, Prussia and England were on good terms

and the Prussian navy spent much time in British ports. Tirpitz

reported that Plymouth was more hospitable to German sailors than was Kiel,

while it was also easier to obtain equipment and supplies there, which

were of better quality than available at home. At this time the British

navy was pleased to assist that of Prussia in its development and a

considerable respect grew up in Prussian officers of their British

counterparts.

Unification of Germany in 1871 again meant a change of name, to the Kaiserliche Marine or Imperial Navy. On 25 May 1872 he was promoted to Lieutenant (Leutnant zur See) and on 18 November 1875 to the equivalent of Senior Lieutenant (Kapitänleutnant). In 1877 he was chosen to visit the Whitehead Torpedo development works at Fiume and

afterwards was placed in charge of the German torpedo section, later

renamed the torpedo inspectorate. By 1897 a working device had been

produced, but even under demonstration conditions Tirpitz reckoned it

was as likely to miss a target as to hit it. On 17 September 1881 he

became Lieutenant Commander (Korvettenkapitän). From developing torpedoes, Tirpitz moved on to developing torpedo boats to deliver them. The Navy State Secretary, Count Leo von Caprivi,

was a distant relative and Tirpitz now worked with him on the

development of tactics. Caprivi envisioned that the boats would be used

defensively against their most likely enemy, France, but Tirpitz set

about developing plans to attack the French home port of Cherbourg. Tirpitz later described his time with torpedo boats as, 'the eleven best years of my life'. In 1887 the torpedo boats escorted prince Wilhelm to

attend the Golden Jubilee celebrations of his grandmother, Queen

Victoria. This was the first time Tirpitz met Wilhelm. In July 1888

Caprivi was succeeded by Alexander von Monts. Torpedo boats were no longer considered important, and Tirpitz requested transfer, commanding the cruisers SMS Preussen and then SMS Württenberg. He was promoted to Captain (Kapitän zur See)

24 November 1888 and in 1890 became chief of staff of the Baltic

Squadron. On one occasion the Kaiser was attending dinner with the

senior naval officers at Kiel and asked their opinion on how the navy

should develop. Finally the question came to Tirpitz and he advised

building battleships. This was an answer which appealed to the Kaiser,

and nine months later he was transferred to Berlin to work on a new

strategy for creating a High seas fleet. Tirpitz appointed a staff of

officers he had known from his time with the torpedo boats and

collected together all sorts of vessels as stand-in battleships to

conduct exercises to test out tactics. On 1 December 1892 he made a

presentation of his findings to the Kaiser. This brought him into

conflict with the Navy State Secretary, Admiral Friedrich von Hollmann.

Hollmann was responsible for procurement of ships, and had a policy of

collecting ships as funding permitted. Tirpitz had concluded that the

best fighting arrangement was a squadron of eight identical

battleships, rather than any other combination of ships with mixed

abilities. Further ships should then be added in groups of eight.

Hollmann favored a mixed fleet including cruisers for long distance

operations overseas. Tirpitz believed that in a war no amount of

cruisers would be safe unless backed up by sufficient battleships. Captain Tirpitz became chief of the naval staff in 1892 and was made a Rear Admiral in 1895. In

autumn 1895, frustrated by the non-adoption of his recommendations,

Tirpitz asked to be replaced. The Kaiser, not wishing to lose him asked

instead that he prepare a set of recommendations for future ship

construction. This was delivered in January 3 1896, but the timing was

bad as it coincided with raids into the Transvaal in South Africa by

pro British forces against pro German. The Kaiser immediately set his

mind to demanding cruisers which could operate at a distance and

influence the war. Hollman was tasked with obtaining money from the Reichstag for a building program, but failed to gain funding for enough ships to satisfy anyone. Chancellor Hohenloe saw no sense in naval enlargement and reported back that the Reichstag opposed it. Admiral Gustav von Senden-Bibran,

Chief of the Naval Cabinet, advised that the only possibility lay in

replacing Hollmann: Wilhelm impulsively decided to appoint Tirpitz. Meanwhile

however, Hollmann had obtained funding for one battleship and three

large cruisers. It was felt that replacing him before the bill had

completed approval through the Reichstag would be a mistake. Instead,

Tirpitz was placed in charge of the German East Asia Squadron in

the Far East but with a promise of appointment as Secretary at a

suitable moment. The cruiser squadron operated from British facilities

in Hong Kong which were far from satisfactory as the German ships

always took second place for available docks. Tirpitz was instructed to

find a suitable site for a new port, selecting four possible sites.

Although he initially favored the bay at Kiautschou/Tsingtao others

in the naval establishment advocated a different location and even

Tirpitz wavered on his commitment in his final report. A 'lease' on the

land was acquired in 1898 after it was fortuitously occupied by German

forces. On 12 March 1896 the Reichstag cut back Hollmann's

appropriation of 70 million marks to 58 million, and Hollman offered

his resignation. Tirpitz was summoned home and offered the post of

Secretary of the Imperial Navy office (Reichsmarineamt).

He went home the long way, touring the USA on the way and arriving in

Berlin 6 June 1897. He was pessimistic of his chances of succeeding

with the Reichstag. On

15 June Tirpitz presented a memorandum on the makeup and purpose of the

German fleet to the Kaiser. This defined the principal enemy as

England, and the principal area of conflict to be that between

Heligoland and the Thames. Cruiser warfare around the globe was deemed

impractical because Germany had few bases to resupply ships, while the

chief need was for as many battleships as possible to take on the

English fleet. A target was outlined for two squadrons of eight

battleships, plus a fleet flagship and two reserves. This was to be

completed by 1905 and cost 408 million marks, or 58 million per year,

the same as the existing budget. The proposal was innovative in several

ways. It made a clear statement of naval needs, whereas before the navy

had grown piecemeal. It set out the program for seven years ahead,

which neither the Reichstag nor the navy should change. It defined a

change in German foreign policy so as to justify the existence of the

fleet: England up to this point had been friendly, now it was

officially an enemy. The Kaiser agreed the plan and Tirpitz retired to

St Blazien in the Black Forest with a team of naval specialists to

draft a naval bill for

presentation to the Reichstag. Information about the plan leaked out to

Admiral Knorr in the Naval High Command. Tirpitz agreed a joint

committee to discuss changes in the navy, but then arranged that it

never receive any information. Similarly, he arranged a joint committee

with the Treasury State Secretary to discuss finance, which never

discussed anything. Meanwhile he continued his best efforts to convince

the Kaiser and chancellor, so that in due course he could announce the

issues had already been decided at a higher level and thereby avoid

debate. Once

the bill was nearly complete Tirpitz started a round of visits to

obtain support. First he visited the former Chancellor and elder

statesman, Otto von Bismarck.

Armed with the announcement that the Kaiser intended to name the next

ship launched 'Furst Bismarck', he persuaded the former chancellor, who

had been dismissed from office for disagreement with William, to

modestly support the proposals. Tirpitz now visited the King of Saxony,

Prince Regent of Bavaria, Grand Duke of Baden and Oldenburg and the

councils of the Hanseatic towns.

On October 19th the draft bill was sent to the printers for

presentation to the Reichstag. Tirpitz' approach was to be as

accommodating with the deputies as he could. He was patient and good

humoured, proceeding on the assumption that if everything was explained

carefully, then the deputies would naturally be convinced. Groups were

invited to private meetings to discuss the bill. Tours of ships and

shipyards were arranged. The Kaiser and Chancellor stressed that the

fleet was only intended for protection of Germany, but so that even a

first class power might think twice before attacking. Highlights from a

letter Bismark wrote were read out in the Reichstag, though not

mentioning passages where he expressed reservations. Papers were

circulated showing the relative size of foreign fleets, and how much

Germany had fallen behind, particularly when considering the great

power of her army compared to others. A

press bureau was created in the Navy Ministry to ensure journalists

were thoroughly briefed, and to politely answer any and all objections.

Pre-written articles were provided for the convenience of journalists.

University professors were invited to speak on the importance of

protecting German trade. The German Navy League was formed to

popularise the idea of world naval power and its importance to the

Empire. It was argued that colonies overseas were essential, and

Germany

deserved her 'place in the sun'. League membership grew from 78,000 in

1898, to 600,000 in 1901 and 1.1 million by 1914. Special attention

was given to members of the budget committee who would consider the

bill in detail. Their interests and connections were analysed to find

ways to influence them. Steel magnate Fritz Krupp and shipowner Albert

Balin of the Hamburg-America Line were invited to speak on the benefits

of the bill to trade and industry. Objections

were raised that the bill surrendered one of the most important powers

of the Reichstag, that of annually scrutinising expenditure.

Conservatives felt that expenditure on the navy was wasted, and that if

money was available it should go to the army, which would be the

deciding factor in any likely war. Eugen Richter of

the Liberal Radical Union opposing the bill observed that if it was

intended for Germany now seriously to take up the Trident to match its

other forces then such a small force would not suffice and there would

be no end to ship building. August Bebel of the Social Democrats argued

that there existed a number of deputies who were Anglophobes and wished

to pick a fight with England, but that to imagine such a fleet could

take on the Royal Navy was insanity and anyone saying it belonged in

the madhouse. Yet

by the end of the debates the country was convinced that the bill would

and should be passed. On 26 March 1898 it did so, by a majority of 212

to 139. All those around the Kaiser were ecstatic at their success.

Tirpitz as navy minister was elevated to a seat on the Prussian

Ministry of State. His influence and importance as the man who had

accomplished this miracle was assured and he was to remain at the

center of government for the next nineteen years. One

Year after the passage of the bill Tirpitz appeared before the

Reichstag and declared his satisfaction with it. The specified fleet

would still be smaller than the French or British, but would be able to

deter the Russians in the Baltic. Within another year all had changed.

In October 1899 the Boer war broke out between the British and Dutch in

Africa. In January 1900 a British cruiser intercepted three German mail

steamers and searched them for war supplies intended for Boers. Germany

was outraged and the opportunity presented itself for a second naval

bill. The second bill increased the number of battleships from nineteen

to thirty-eight. This would form four squadrons of eight ships, plus

two flagships and four reserves. The bill now spanned seventeen years

from 1901 to 1917 with the final ships being completed by 1920. This

would constitute the second largest fleet in the world and although no

mention was made in the bill of specific enemies, it made several

general mentions of a greater power which it was intended to oppose.

There was only one navy which could be meant. On 5 December 1899

Tirpitz was promoted to Vice-Admiral. The bill passed on 20 June 1900. Specifically

written into the preamble was an explanation of Tirpitz' Risk theory.

Although the German fleet would be smaller, it was likely that an enemy

with a world spanning empire would not be able to concentrate all its

forces in local waters. Even if it could, the German fleet would still

be sufficiently powerful to inflict significant damage in any battle.

Sufficient damage that the enemy would be unable to maintain its other

naval commitments and must suffer irreparable harm. Thus no such enemy

would risk an engagement. Privately Tirpitz acknowledged that a second

risk existed: that Britain, seeing its growing enemy might choose to

strike first, destroying the German fleet before it grew to a dangerous

size. A similar course had been taken before, when Nelson sank Danish

ships to prevent them falling into French hands, and would be again in

World War II when French ships were sunk to prevent them falling to the

Germans. A term, to copenhagenize even

existed in English for this. Tirpitz calculated this danger period

would end in 1904 or 1905. In the event, Britain responded to the

increased German building program by building more ships herself and

the theoretical danger period extended itself to beyond the start of

World War I. As a reward for the successful bill Tirpitz was ennobled

to the hereditary ‘von’ Tirpitz in 1900. Tirpitz

noted the difficulties in his relationship with the Kaiser. Wilhelm

respected him as the only man who had succeeded in persuading the

Reichstag to start and then increase a world class navy, but he

remained Emperor and unpredictable. He was fanatical about the navy,

but would come up with wild ideas for improvements, which Tirpitz had

to deflect to maintain his objectives. Each Summer Tirpitz would go to

St Blasien with his aids to work on naval plans. Then in September he

would travel to the Kaiser's retreat at Romintern, where Tirpitz found

he would be more relaxed and willing to listen to a well argued

explanation. Three

supplementary naval bills ('Novelles') were passed, in June 1906, April

1908 and June 1912. The first followed German defeats in Morocco, and

added six large cruisers to the fleet. The second followed fears of

British encroachment, and reduced the replacement time which a ship

would remain in service from 25 to 20 years. The third was caused by the Agadir Crisis where again Germany had to draw back. This time three more battleships were added. The

first naval law caused little alarm in Britain. There was already in

force a dual power standard defining the size of the British fleet as

at least that of the next two largest fleets combined. There was now a

new player, but her fleet was similar in size to the other two possible

threats, Russia and France, and a number of battleships were already

under construction. The second naval law, however, caused serious

alarm: eight King Edward class

battleships were ordered in response. It was the regularity and

efficiency with which Germany was now building ships, which were seen

to be as good as any in the world, which raised concern. Information

about the design of the new battleships suggested they were only

intended to operate within a short range of a home base and not to stay

at sea for extended periods. They seemed designed only for operations

in the North Sea. The result was that Britain abandoned its policy of

isolation which had held force since the time of Nelson and began to

look for allies against the growing threat from Germany. Ships were

withdrawn from around the world and brought back to British waters,

while construction of new ships increased. Tirpitz'

design to achieve world power status through naval power, while at the

same time addressing domestic issues, is referred to as the Tirpitz Plan. Politically, the Tirpitz Plan was marked by the Fleet Acts of

1898, 1900, 1908 and 1912. By 1914, they had given Germany the

second-largest naval force in the world (roughly 40% smaller than the Royal Navy). It included seventeen modern dreadnoughts, five battlecruisers, twenty-five cruisers and twenty pre-dreadnought battleships as well as over forty submarines.

Although including fairly unrealistic targets, the expansion program

was sufficient to alarm the British, starting a costly naval arms race

and pushing the British into closer ties with the French. Tirpitz developed a "risk theory" (an analysis which today would be considered part of game theory) whereby, if the German Navy reached a certain level of strength relative to the British Navy, the British

would try to avoid confrontation with Germany (that is, maintain a fleet in being).

If the two navies fought, the German Navy would inflict enough damage

on the British that the latter ran a risk of losing their naval

dominance. Because the British relied on their navy to maintain control

over the British Empire,

Tirpitz felt they would rather maintain naval supremacy in order to

safeguard their empire, and let Germany become a world power, than lose

the empire as the cost of keeping Germany less powerful. This theory

sparked a naval arms race between Germany and Great Britain in the first decade of the 20th century. This theory was based on the assumption that Great Britain would have to send its fleet into the North Sea to

blockade the German ports (blockading Germany was the only way the

Royal Navy could seriously harm Germany), where the German Navy could

force a battle. However due to Germany's geographic location, Great

Britain could blockade Germany by closing the entrance to the North Sea

in the English Channel and the area between Bergen and the Shetland Islands.

Faced with this option a German Admiral commented, "If the British do

that, the role of our navy will be a sad one," correctly predicting the

role the surface fleet would have during World War I. Tirpitz had been made a Grand Admiral in

1911, without patent (the document that accompanied formal promotions

personally signed at this level by the Kaiser himself). At that time,

the German navy had only four ranks for admirals: Rear Admiral,

(Konteradmiral, equal to a General major, with no pips on the shoulder

board); Vice Admiral (Vizeadmiral, equal to a General leutnant, with one

pip); Admiral (equal to a General der Infanterie, with two pips), and

Grand Admiral (equal to a Field Marshal). Von Tirpitz’s shoulder boards

had four pips revealing and he never received a Grand Admiral baton or

the associated insignia. Despite the building program he felt the war

had come too soon for a successful surface challenge to the Royal Navy

as the Fleet Act of 1900 had included a seventeen-year timetable.

Unable to influence naval operations from his purely administrative

position, Tirpitz became a vocal spokesman for an unrestricted U-boat warfare, which he felt could break the British stranglehold on Germany's sea

lines of communication. Interestingly, his construction policy never

bore out his political stance on submarines, and by 1917 there was a

severe shortage of newly built submarines. When restrictions on the

submarine war were not lifted, he fell out with the Emperor and was

compelled to resign on March 15, 1916. He was replaced as Secretary of

State of the Imperial Naval Office by Eduard von Capelle. In 1917 Tirpitz was co-founder of the Pan-Germanic and nationalist Fatherland Party (Deutsche Vaterlandspartei). The party was organised jointly by Heinrich Claß, Conrad Freiherr von Wangenheim, Tirpitz as chairman and Wolfgang Kapp as

his deputy. The party attracted opponents of a negotiated peace and

organised opposition to the parliamentary majority seeking peace

negotiations. It sought to bring together outside parliament all

parties on the political right, which had not previously been done. At

its peak in summer 1918 it had around 1,250,000 members. It proposed

the Generals Erich Ludendorff and Paul von Hindenburg as

'people's emperors' of a military state whose legitimacy was based upon

war and war aims instead of parliamentary government of the empire.

Internally there were calls for a coup against the state, to be led by

Hindenburg and Ludendorff, even against the emperor if necessary.

Tirpitz' experience with the navy league and mass political agitation

convinced him that the means for a coup was ready. Tirpitz

considered one of the main aims of the war must be annexation of

territory in the west to allow Germany to develop as a world power.

This meant holding the Belgium ports of Zeebrugge and Ostend, with an

eye to the main enemy, England. He proposed a separate peace treaty

with Russia giving them access to the ocean. Germany would be a very

great continental state but could maintain its world position only by

expanding world trade and continuing the fight against England. He

complained of indecision and ambiguity in German policy, humanitarian

ideas of self-preservation, a policy of appeasement of neutrals at the

expense of vital German interests and begging for peace. He called for

vigorous warfare without regard for diplomatic and commercial

consequences and supported the most extreme use of weapons

(unrestricted submarine warfare). The policies had a curious mixture of

hatred, admiration, envy and imitation of the British Empire. From 1908 to 1918 Tirpitz was a member of the Prussian house of Lords. After Germany's defeat he supported the right-wing Deutschnationale Volkspartei (DNVP, German National People Party) and sat for it in the Reichstag from 1924 until 1928. Tirpitz died in Ebenhausen, near Munich, on 6 March 1930.