<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Amalie Emmy Noether, 1882

- Painter José Victoriano González-Pérez (Juan Gris), 1887

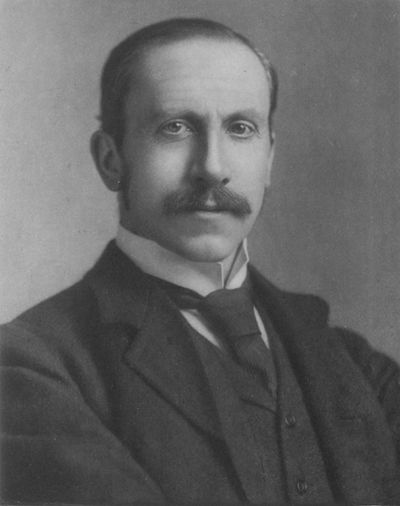

- Governor of the Cape Colony Alfred Milner, 1854

PAGE SPONSOR

Alfred Milner, 1st Viscount Milner of St James's and Cape Town KG, GCB,GCMG, PC (23 March 1854 — 13 May 1925) was a British statesman and colonial administrator who played an influential leadership role in the formulation of foreign and domestic policy between the mid 1890s and early 1920s. He was also the key British Empire figure in the events leading up to and following the Boer War of 1898 – 1902 and, while serving as High Commissioner, is additionally noted for mentoring a gathering of young members of the South African Civil Service, informally known as Milner's Kindergarten who, in some cases, themselves became important figures in administering the British Empire. In the later part of his life, from December 1916 to November 1918, he was second only to Prime Minister David Lloyd George in the decision making process guiding Britain through the crucial period leading to the end of World War I.

Milner's German ancestry dates to his paternal grandmother, married to an Englishman who settled in the Grand Duchy of Hesse (modern state of Hesse in west-central Germany). Their son, Charles Milner, who was educated in Hesse and England, established himself as a physician with a practice in London and later became Reader in English at Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen in the Kingdom of Württemberg (modern state of Baden-Württemberg). His wife was a daughter of Major General John Ready, former Lieutenant Governor of Prince Edward Island and later the Isle of Man. Their only son, Alfred Milner, was born in the Hessian town of Gießenand educated first at Tübingen, then at King's College School and, from 1872 to 1876, as a scholar of Balliol College, Oxford, studying under the classicist theologian Benjamin Jowett. Having won the Hertford, Craven, Eldon and Derby scholarships, he graduated in 1877 with a first class in classics and was elected to a fellowship at New College, leaving, however, for London in 1879. At Oxford he formed a close friendship with young economic historian Arnold Toynbee, writing a paper in support of his theories of social work and, in 1895, twelve years after his death at the age of 30, penning a tribute, Arnold Toynbee: a Reminiscence.

Although authorised to practice law after being called to the bar at the Inner Temple in 1881, he joined the staff of the Pall Mall Gazette under John Morley, becoming assistant editor to William Thomas Stead. In 1885 he abandoned journalism for a potential political career as the Liberal candidate for the Harrow division of Middlesex, but lost in the general election. Holding the post of private secretary to George Goschen, he rose in rank when, in 1887, Goschen became Chancellor of the Exchequer and, two years later, used his influence to have Milner appointed under-secretary of finance in Egypt. He remained in Egypt for four years, his period of office coinciding with the first great reforms, after the danger of bankruptcy had been avoided. Returning to England in 1892, he published England and Egypt which, at once, became the authoritative account of the work done since the British occupation. Later that year he received an appointment as chairman of the Board of Inland Revenue. In 1894 he was made CB and in 1895 KCB. Sir Alfred Milner remained at the Board of Inland Revenue until 1897. He was regarded as one of the clearest-headed and most judicious officials in the British service, and his position as a man of moderate Liberal views, who had been so closely associated with Goschen at the Treasury, Cromer in Egypt and Hicks-Beach (Lord St Aldwyn) and Sir William Vernon Harcourt while at the Inland Revenue, marked him as one in whom all parties might have confidence. The moment for testing his capacity in the highest degree had now come.

In April, Lord Rosmead resigned his posts of High Commissioner for Southern Africa and Governor of Cape Colony. The situation resulting from the Jameson raid was one of the greatest delicacy and difficulty, and Joseph Chamberlain, now colonial secretary, selected Milner as Lord Rosmead's successor. The choice was cordially approved by the leaders of the Liberal party and warmly recognized at a 28 March 1897 farewell dinner presided over by the future prime minister Herbert Henry Asquith. The appointment was avowedly made in order that an acceptable British statesman, in whom public confidence was reposed, might go to South Africa to consider all the circumstances and to formulate a policy which should combine the upholding of British interests with the attempt to deal justly with the Transvaal and Orange Free State governments.

Sir Alfred Milner reached the Cape in May 1897 and after the difficulties with President Kruger over the Aliens' Law had been patched up, he was free by August to make himself personally acquainted with the country and peoples before deciding on the lines of policy to be adopted. Between August 1897 and May 1898 he travelled through Cape Colony, the Bechuanaland Protectorate, Rhodesia and Basutoland. The better to understand the point of view of the Cape Dutch and the burghers of the Transvaal and Orange Free State, Milner also during this period learned both Dutch and the South African "Taal". He came to the conclusion that there could be no hope of peace and progress in South Africa while there remained the "permanent subjection of British to Dutch in one of the Republics". Milner was referring to the situation in the Transvaal where, in the aftermath of the discovery of gold, thousands of fortune seekers had flocked from all over Europe, but mostly Britain. This influx of foreigners, referred to as "Uitlanders", threatened their republic, and Transvaal's President Kruger refused to give the "Uitlanders" the right to vote. The Afrikaner farmers, known as Boers, had established the Transvaal as their promised land, after their Great Trek out of Cape Colony, a trek whose purpose was to remove themselves as far as possible from British rule. They had already successfully defended the Transvaal's annexation by the British Empire during the first Anglo-Boer War, a conflict that had emboldened them and resulted in a peace treaty which, lacking a highly convincing pretext, made it very difficult for Britain to justify diplomatically another annexation of the Transvaal.

Independent

Transvaal thus stood in the way of Britain's ambition to control all of

Africa from Cape to Cairo. Milner realised that, with the discovery of

gold in the Transvaal, the balance of power in South Africa had shifted

from Cape Town to Johannesburg.

He feared that if the whole of South Africa was not quickly brought

under British control, the newly-wealthy Transvaal, controlled by

Afrikaners, could unite with Cape Afrikaners and jeopardise the entire

British position in South Africa. Milner also realised — as was shown by

the triumphant re-election of Paul Kruger to the presidency of the

Transvaal in February 1898 — that the Pretoria government would never on its own initiative redress the grievances of the "Uitlanders". This gave Milner the pretext to use the "Uitlander" question to his advantage. In a 3 March 1898 speech delivered at Graaff Reinet,

an Afrikaner Bond stronghold in the British controlled Cape, he

outlined his determination to secure freedom and equality for British

subjects in the Transvaal, and he urged the Dutch colonists to induce

the Pretoria government to assimilate its institutions, and the temper

and spirit of its administration, to those of the free communities of

South Africa. The effect of this pronouncement was great and it alarmed

the Afrikaners who, at this time, viewed with apprehension the virtual

resumption by Cecil Rhodes of leadership of Cape's Progressive (British) Party. Milner

had an unfavorable view of Afrikaners and, as a matter of philosophy,

saw the British as "a superior race". Thus, with limited interest in

peaceful resolution of the conflict, he came to the view that British

control of the region could only be achieved through war. A negotiated

peace was problematic as the Afrikaners outnumbered the British in both

the Transvaal, Free State and the Cape. Milner was not alone in his

views as evidenced in an 11 March letter written by another Briton, John X. Merriman, to President Steyn of

the Orange Free State, "The greatest danger lies in the attitude of

President Kruger and his vain hope of building up a State on a

foundation of a narrow unenlightened minority, and his obstinate

rejection of all prospect of using the materials which lie ready to his

hand to establish a true republic on a broad liberal basis. Such a

state of affairs cannot last. It must break down from inherent

rottenness." Although not all Afrikander Bond leaders

liked Kruger, they were ready to support him whether or not he granted

reforms and, by the same result, contrived to make Milner's position

untenable. His difficulties were increased when, at the general

election in Cape Colony, the Bond obtained a majority. In October 1898,

acting strictly in a constitutional manner, Milner called upon William Philip Schreiner to

form a ministry, though aware that such a ministry would be opposed to

any direct intervention of Great Britain in the Transvaal. Convinced

that the existing state of affairs, if continued, would end in the loss

of South Africa by Britain, Milner came to England in November 1898. He

returned to Cape Colony in February 1899, fully assured of Joseph

Chamberlain's support, though the government still clung to the hope

that the moderate section of the Cape and Orange Free State Dutch would

induce Kruger to give the vote to the Uitlanders. He found the situation more critical than when he had left, ten weeks previously. Johannesburg was in a ferment, while William Francis Butler, who acted as high commissioner in Milner's absence, had allowed the inference that he did not support Uitlander grievances. On

4 May Milner penned a memorable dispatch to the Colonial Office, in

which he insisted that the remedy for the unrest in the Transvaal was

to strike at the root of the evil --- the political impotence of the

injured. "It may seem a paradox," he wrote, "but it is true that the

only way for protecting our subjects is to help them to cease to be our

subjects." The policy of leaving things alone only led from bad to

worse, and "the case for intervention is overwhelming." Milner felt

that only the enfranchisement of the Uitlanders in the Transvaal would

give stability to the South African situation. He had not based his

case against the Transvaal on the letter of the Conventions, and

regarded the employment of the word "suzerainty" merely as an

"etymological question," but he realized keenly that the spectacle of

thousands of British subjects in the Transvaal in the condition of "helots"

(as he expressed it) was undermining the prestige of Great Britain

throughout South Africa, and he called for "some striking proof" of the

intention of the British government not to be ousted from its

predominant position. This dispatch was telegraphed to London, and was

intended for immediate publication; but it was kept private for a time

by the home government. Its tenor was known, however, to the leading politicians at the Cape, and at the insistence of Jan Hendik Hofmeyr a peace conference was held (31 May – 5 June) at Bloemfontein between

the high commissioner and Transvaal President Kruger. Milner made three

demands, which he knew could not be accepted by Kruger: The enactment

by the Transvaal of a franchise law which would at once give the

"Uitlanders" the vote; Use of English in the Transvaal parliament and;

That all laws of the parliament should be vetted and approved by the

British parliament. Realizing the untenability of his position, Kruger

left the meeting in tears.

When the Second Boer War broke

out in October 1899, Milner rendered the military authorities

"unfailing support and wise counsels", being, in Lord Roberts's phrase

"one whose courage never faltered". In February 1901, he was called

upon to undertake the administration of the two Boer states, both now

annexed to the British Empire, though the war was still in progress. He

thereupon resigned the governorship of Cape Colony, while retaining the

post of high commissioner. During this time at the helm a number of

concentration camps were created where 27,000 Boer women and children

and more than 14,000 black South Africans died. The work of

reconstructing the civil administration in the Transvaal and Orange River Colony could

only be carried on to a limited extent while operations continued in

the field. Milner therefore returned to England to spend a "hard-begged

holiday," which was, however, mainly occupied in work at the Colonial

Office. He reached London on 24 May 1901, had an audience with King Edward VII on

the same day, was made a GCB and privy councillor, and was raised to

the peerage with the title of Baron Milner of St James's and Cape Town.

Speaking next day at a luncheon given in his honor, answering critics

who alleged that with more time and patience on the part of Great

Britain, war might have been avoided, he asserted that what they were

asked to "conciliate" was "panoplied hatred, insensate ambition,

invincible ignorance." Meanwhile

the diplomacy of 1899 and the conduct of the war had caused a great

change in the attitude of the Liberal party in England towards Lord

Milner, whom a prominent Member of Parliament, Leonard Courtney, even characterized as "a lost mind". A violent agitation for his recall, joined by the Liberal Party leader, Henry Campbell-Bannerman,

was organized, however unsuccessfully and, in August, Milner returned

to South Africa, plunging into the herculean task of remodelling the

administration. In the negotiations for peace he was associated with

Lord Kitchener, and the terms of surrender, signed in Pretoria on 31

May 1902, were drafted by him. In recognition of his services he was,

on 1 July, made a viscount. Around this time he became a member of the Coefficients dining club of social reformers set up in 1902 by the Fabian Society campaigners Sidney and Beatrice Webb. On

21 June, immediately following the conclusion of signatory and

ceremonial developments surrounding the end of hostilities, Milner

published the Letters Patent establishing the system of crown colony

government in the Transvaal and Orange River colonies, and changing his

title of administrator to that of governor. The reconstructive work

necessary after the ravages of the war was enormous. He provided a

steady revenue by the levying of a 10% tax on the annual net produce of

the gold mines, and devoted special attention to the repatriation of

the Boers, land settlement by British colonists, education, justice,

the constabulary, and the development of railways. At Milners

suggestion the British government sent Henry Birchenough a

businessman and old friend of Milners as special trade commissioner to

South Africa with the task of preparing a Blue Book on trade prospects

in the aftermath of the war. While

this work of reconstruction was in progress, domestic politics in

England were convulsed by the tariff reform movement and Joseph Chamberlain's resignation. Milner, who was then spending a brief

holiday in Europe, was urged by Arthur James Balfour to

take the vacant post of secretary of state for the colonies. He

declined the offer on 1 October 1903, considering it more important to

complete his work in South Africa, where economic depression was

becoming pronounced. As of December 1903, he was back in Johannesburg,

and had to consider the crisis in the gold-mining industry caused by

the shortage of native labor. Reluctantly he agreed, with the assent of

the home government, to the proposal of the mine owners to import

Chinese coolies on a three-year contract with the first batch of

Chinese reaching the Rand in June 1904. In

the latter part of 1904 and the early months of 1905 Milner was engaged

in the elaboration of a plan to provide the Transvaal with a system of

representative government, a half-way house between crown colony

administration and that of self-government. Letters patent providing

for representative government were issued on 31 March 1905. For

some time he had been suffering health difficulties from the incessant

strain of work, and determined a need to retire, leaving Pretoria on 2

April and sailing for Europe the following day. Speaking in

Johannesburg on the eve of his departure, he recommended to all

concerned the promotion of the material prosperity of the country and

the treatment of Dutch and British on an absolute equality. Having

referred to his share in the war, he added: "What I should prefer to be

remembered by is a tremendous effort subsequent to the war not only to

repair the ravages of that calamity but to re-start the colonies on a

higher plane of civilization than they have ever previously attained." He

left South Africa while the economic crisis was still acute and at a

time when the voice of the critic was audible everywhere but, in the

words of the colonial secretary Alfred Lyttelton,

he had in the eight eventful years of his administration laid deep and

strong the foundation upon which a united South Africa would arise to

become one of the great states of the empire. Upon returning home, his university bestowed upon him the honorary degree of DCL. Experience

in South Africa had shown him that underlying the difficulties of the

situation there was the wider problem of imperial unity. In his

farewell speech at Johannesburg he concluded with a reference to the

subject. 'When we who call ourselves Imperialists talk of the British

Empire, we think of a group of states bound, not in an alliance or

alliances that can be made and unmade but in a permanent organic union.

Of such a union the dominions of the sovereign as they exist to-day are

only the raw material.' This thesis he further developed in a magazine

article written in view of the colonial conference held in London in

1907. He advocated the creation of a permanent deliberative imperial

council, and favored preferential trade relations between the United

Kingdom and the other members of the empire; and in later years he took

an active part in advocating the cause of tariff reform and Imperial Preference. In 1910 he became a founder of The Round Table — A Quarterly Review of the Politics of the British Empire, which helped to promote the cause of imperial federation.

In March 1906, a motion censuring Lord Milner for an infraction of the Chinese labour ordinance, in not forbidding light corporal punishment of coolies for minor offences in lieu of imprisonment, was moved by a Radical member of the House of Commons.

On behalf of the Liberal government an amendment was moved, stating

that 'This House, while recording its condemnation of the flogging of

Chinese coolies in breach of the law, desires, in the interests of

peace and conciliation in South Africa, to refrain from passing censure

upon individuals'. The amendment was carried by 355 votes to 135. As a

result of this left-handed censure, a counter demonstration was

organized, led by Sir Bartle Frere,

and a public address, signed by over 370,000 persons, was presented to

Lord Milner expressing high appreciation of the services rendered by

him in Africa to the crown and empire.

Upon

his return from South Africa, Viscount Milner occupied himself mainly

with business interests in London, becoming chairman of the Rio Tinto Zinc mining

company, though he remained active in the campaign for imperial free

trade. In 1906 he became a director of the Joint Stock Bank, a

precursor of the Midland Bank. In the period 1909 to 1911 he was a strong opponent of the budget of David Lloyd George and the subsequent attempt of the Liberal government to curb the powers of the House of Lords. Since

Milner, who was a leading conservative, was the only Briton who had

experience in civil direction of a war, Lloyd George turned to him in

December 1916 when he formed his national government. He was made a

member of the five person War Cabinet. Milner was probably the most competent member of the war cabinet after

the prime minister himself and consequently became Lloyd George's fire

fighter in many crises. He gradually became the second most powerful

voice in the conduct of the war. Despite his conservative credentials

he also gradually became disenchanted with the military leadership of

the country which exercised a disproportionate influence on the conduct

of war because of conservative support. He backed Lloyd George, who was

even more disenchanted with the military, in his successful move to

remove Edward Carson from the Admiralty, and in his less successful attempt to prevent the disastrous Third Battle of Ypres in 1917. Milner was also a chief author of the Balfour Declaration of 1917, although it was issued in the name of Arthur Balfour. He was a highly outspoken critic of the Austro-Hungarian war in Serbia arguing

that "there is more widespread desolation being caused there (than) we

have been familiar with in the case of Belgium". He was an earnest

advocate of inter-allied cooperation, attending an Allied conference in St. Petersburg in

February 1917 and, as representative of the British cabinet, was on a

March 1918 visit to France when the Germans launched their great

offensive, and was instrumental in getting General Ferdinand Foch appointed as Allied Generalissimo on 26 March. On 19 April he was appointed Secretary of State for War and presided over the army council for the remainder of the war. Following the khaki election of December 1918, he was appointed Colonial Secretary and, in that capacity, attended the 1919 Paris Peace Conference where, on behalf of United Kingdom, he became one of the signatories of the Treaty of Versailles.

After the War, Lord Milner assisted the Royal Agricultural Society in procuring Fordson tractors for the plowing and planting of grasslands, and communicated directly with Henry Ford by telegraph,

per Henry Ford's book, 'My Life and Work', regarding Chapter 14. His

last great public service was, after serious rioting broke out, a

mission to Egypt from December 1919 to March 1920 to make recommendations on British-Egyptian relations, specifically how to

reconcile the British protectorate established in 1915 with Sa'd Zaghlul's

calls for self-government. The report of the Milner Commission formed

the basis of a settlement which lasted for a number of years. Right

until the end of his life, Lord Milner would call himself a "British

race patriot" with grand dreams of a global Imperial parliament,

headquartered in London, seating delegates of British descent from

Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. He retired in February

1921 and was appointed a Knight of the Garter (KG) in the same month. Later that year he married Lady Violet Georgina Gascoyne-Cecil, widow of Lord Edward Cecil and remained active in the work of the Rhodes Trust, while accepting, at the behest of Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin,

the chairmanship of a committee to examine a new imperial preference

tariff. His work, however, proved abortive when, following an election, Ramsay MacDonald assumed the office of Prime Minister in January 1924. Seven weeks past his 71st birthday, Alfred Milner died at Sturry Court, near Canterbury of sleeping sickness, soon after returning from South Africa. His viscountcy, lacking heirs, died with him.

Found among Milner's papers was his Credo,

which was soon published to great acclaim — "I am a Nationalist and not

a

cosmopolitan .... I am a British (indeed primarily an English)

Nationalist. If I am also an Imperialist, it is because the destiny of

the English race, owing to its insular position and long supremacy at

sea, has been to strike roots in different parts of the world. I am an

Imperialist and not a Little Englander because I am a British Race

Patriot ... The British State must follow the race, must comprehend it,

wherever it settles in appreciable numbers as an independent community.

If the swarms constantly being thrown off by the parent hive are lost

to the State, the State is irreparably weakened. We cannot afford to

part with so much of our best blood. We have already parted with much

of it, to form the millions of another separate but fortunately

friendly State. We cannot suffer a repetition of the process."