<Back to Index>

- Agronomist Norman Ernest Borlaug, 1914

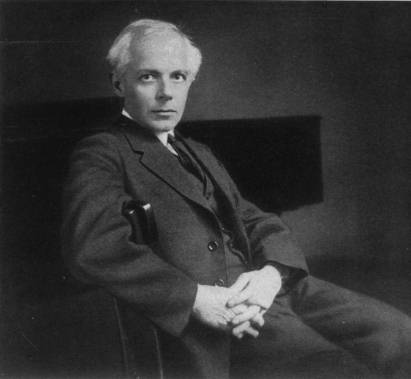

- Composer Béla Viktor János Bartók, 1881

- Anarcho-syndicalist Activist Johann Rudolf Rocker, 1873

PAGE SPONSOR

Béla Viktor János Bartók (March 25, 1881 – September 26, 1945) was a Hungarian composer and pianist. He is considered to be one of the greatest composers of the 20th century and is regarded, along with Liszt, as Hungary's greatest composer. Through his collection and analytical study of folk music, he was one of the founders of ethnomusicology.

Béla

Bartók was born in the small Banatian town of Nagyszentmiklós in Austria-Hungary (now Sânnicolau

Mare, Romania)

on March 25, 1881. He displayed notable musical talent very early in

life: according to his mother, he could distinguish between different

dance rhythms that she played on the piano even before he learned to

speak in complete sentences. By the age of four, he

was able to play 40 pieces on the piano and his mother began formally

teaching him the next year.

Béla

was a small and sickly child and suffered from a painful chronic rash

until the age of five. In 1888, when he was seven,

his father (the director of an agricultural school) died suddenly.

Béla's mother then took him and his sister, Erzsebet, to live in

Nagyszőlős (today Vinogradiv, Ukraine) and then to Pozsony (German: Pressburg, today Bratislava, Slovakia). In Pozsony, Béla gave his first

public recital at age eleven to

a warm critical reception. Among the pieces he played was his own first

composition, written two years previously: a short piece called "The

Course of the Danube". Shortly thereafter László

Erkel accepted him as a pupil. Bartók

studied piano under István

Thomán, a former student of Franz Liszt,

and composition under János

Koessler at the Royal Academy

of Music in Budapest from

1899 to 1903. There he met Zoltán

Kodály, who influenced him greatly and became his

lifelong friend and colleague. In 1903, Bartók wrote his first

major orchestral work, Kossuth,

a symphonic poem

which honored Lajos Kossuth,

hero of the Hungarian

Revolution of 1848. The music of Richard Strauss,

whom he met in 1902 at the Budapest premiere of Also sprach

Zarathustra, was

very

influential on his early work. When visiting a holiday resort in

the summer of 1904, Bartók overheard the eighteen year old

nanny, Lidi Dósa from Kibéd in

Maros-Torda in Transylvania sing folk songs to the children under her

care. This sparked his life-long dedication to folk music. From 1907

his music also began to be influenced by Claude Debussy,

whose

compositions Kodály had brought back from Paris.

Bartók's large-scale orchestral works were still in the style of Johannes Brahms and

Richard Strauss, but also around this time he wrote a number of small

piano pieces which show his growing interest in folk music. The first

piece to show clear signs of this new interest is the String Quartet

No. 1 in A minor

(1908), which contains folk-like elements. In

1907,

Bartók began teaching as a piano professor at the Royal

Academy. This position freed him from touring Europe as a pianist and

enabled him to stay in Hungary. Among his notable students were Fritz Reiner, Sir Georg Solti, György

Sándor, Ernő Balogh, Lili Kraus,

and, after Bartók moved to the United States, Jack Beeson and Violet Archer. In

1908,

inspired by both their own interest in folk music and by the

contemporary resurgence of interest in traditional national culture, he

and Kodály travelled into the countryside to collect and

research old Magyar folk melodies. Their

findings came as a surprise: Magyar folk music had previously been

categorised as Gypsy music. The classic example

of this misconception is Franz Liszt's

famous Hungarian

Rhapsodies for

piano, which were based on popular art-songs performed by Gypsy bands

of the time. In contrast, the old Magyar folk melodies discovered by

Bartók and Kodály bore little resemblance to the popular

music performed by these Gypsy bands. Instead, they found that many of

the folk songs are based on pentatonic scales similar to those in

Oriental folk traditions, such as those of Central Asia and Siberia. Bartók

and Kodály quickly set about incorporating elements of real

Magyar peasant music into their compositions. Both Bartók and

Kodály frequently quoted folk songs verbatim and wrote pieces

derived entirely from authentic folk melodies. An example is his two

volumes entitled For Children for

solo piano containing 80 folk tunes to which he wrote accompaniment.

Bartók's style in his art music compositions was a synthesis of

folk music, classicism, and modernism. His melodic and harmonic sense

was profoundly influenced by the folk music of Hungary, Romania, and

many other nations, and he was especially fond of the asymmetrical

dance rhythms and pungent harmonies found in Bulgarian

music. Most of his early

compositions offer a blend of nationalist and late Romanticism elements. In

1909,

Bartók married Márta Ziegler. Their son,

Béla II, was born in 1910. In 1911, Bartók wrote what was

to be his only opera, Bluebeard's

Castle, dedicated to Márta. He entered it for a prize

awarded by the

Hungarian Fine Arts Commission, which rejected it out of hand as

un-stageworthy. In 1917 Bartók revised the

score in preparation for the 1918 première, for which he rewrote

the ending. Following the 1919 revolution,

he was pressured by the government to remove the name of the

blacklisted librettist Béla

Balázs (by

then a refugee in Vienna) from the opera. Bluebeard's Castle received

only one revival, in 1936, before Bartók emigrated. For the

remainder of his life, although he was passionately devoted to Hungary,

its people and its culture, he never felt much loyalty to its

government or its official establishments. After

his

disappointment over the Fine Arts Commission prize, Bartók

wrote little for two or three years, preferring to concentrate on

collecting and arranging folk music. He collected first in the Carpathian Basin (the then Kingdom of

Hungary), where he notated Hungarian, Slovakian, Romanian and Bulgarian folk music. He also

collected in Moldavia, Wallachia and in 1913 in Algeria.

However, the outbreak of World War I forced him to stop these

expeditions, and he returned to composing, writing the ballet The Wooden

Prince in

1914–16 and the String Quartet

No. 2 in

1915–17, both influenced by Debussy.

It was The Wooden

Prince which

gave him some degree of international fame. Raised

as a Roman Catholic,

Bartók had by his early adulthood become an atheist and considered the

existence of God as undecidable and unnecessary. He later became

attracted to Unitarianism and publicly converted to

the Unitarian faith in 1916. His son

later became president of the Hungarian Unitarian Church. He

subsequently worked on another ballet, The Miraculous

Mandarin influenced

by Igor Stravinsky, Arnold

Schoenberg, as well as Richard Strauss,

following this up with his two violin sonatas (written in 1921 and 1922

respectively) which are harmonically and structurally some of the most

complex pieces he wrote. The Miraculous

Mandarin, a sordid modern story of prostitution, robbery,

and murder,

was started in 1918, but not performed until 1926 because of its sexual content. He wrote his third and fourth string quartets

in 1927–28, after which his compositions demonstrate his

mature style. Notable examples of this period are Divertimento

for String Orchestra BB 118 (1939) and Music for

Strings, Percussion and Celesta (1936). The String Quartet

No. 5 (1934) is

written in somewhat more traditional style. Bartók wrote his sixth and

last string quartet in 1939, the sadness of which has been related to

the death of Bartók’s mother and the looming war in Europe. Bartók

divorced Márta in 1923, and married a piano student, Ditta

Pásztory. His second son, Péter, was born in 1924. In 1936 he travelled to Turkey to collect and study folk music. He

worked in collaboration with Turkish composer Ahmet

Adnan Saygun mostly around Adana. In

1940, as the European political situation worsened after the outbreak of World War II,

Bartók was increasingly tempted to flee Hungary. He was strongly

opposed to the Nazis and Hungary’s siding with Germany.

After the Nazis had come to power in Germany, he refused to give

concerts there and broke from his German publisher. His views caused

him a great deal of trouble with the establishment in Hungary. Having

first sent his manuscripts out of the country, Bartók

reluctantly emigrated to the U.S. with Ditta Pásztory. They

settled in New York City.

After joining them in 1942, Péter Bartók enlisted in the United States

Navy. Béla Bartók, Jr. remained in Hungary. Bartók

never

became fully at home in the U.S. He initially found it difficult

to compose. Although well-known in America as a pianist,

ethnomusicologist and teacher, he was not well known as a composer and

there was little interest in his music during his final years. He and

his wife Ditta gave concerts. Bartók, who had made some

recordings in Hungary also recorded for Columbia Records after

he came to the U.S; many of these recordings (some with Bartók's

own spoken introductions) were later issued on LP and CD. For

several years, supported by a research fellowship from Columbia

University, Bartók and his wife worked on a large

collection of Serbian and Croatian folk

songs in Columbia's libraries. Bartók's difficulties during his

first years in the US were mitigated by publication royalties, teaching

and performance tours. While their finances were always precarious, it

is a myth that he lived and died in abject poverty and neglect. There

were enough supporters to ensure that there was sufficient money and

work available for him to live on. Bartók was a proud man and

did not easily accept charity. Though he was not a member of ASCAP,

the society paid for any medical care he needed in his last two years

and Bartók accepted this. The

first symptoms of his leukemia began

in 1940, when his right shoulder began to show signs of stiffening. In

1942 symptoms increased and he started having bouts of fever but the

disease was not diagnosed in spite of medical examinations. Finally, in

April 1944, leukemia was diagnosed but by this time little could be

done. As

his body failed, Bartók's creative energy reawakened and he

produced a final set of masterpieces, partly thanks to the violinist Joseph

Szigeti and the conductor Fritz

Reiner (Reiner

had been Bartók's friend and champion since his days as

Bartók's student at the Royal Academy). Bartók's last

work might well have been the String

Quartet No. 6 but for Serge

Koussevitsky's commission for the Concerto

for Orchestra. Koussevitsky's Boston

Symphony Orchestra premièred

the work in December 1944 to highly positive reviews. Concerto for

Orchestra quickly became Bartók's most popular work, although he

did not live to see its full impact. He was also commissioned in 1944 by Yehudi

Menuhin to write a Sonata

for Solo Violin. In 1945

Bartók composed his Piano

Concerto No. 3, a graceful

and almost neo-classical work and he began work on his Viola

Concerto. He had not

completed the scoring at his death. Bartók

died in New York from leukemia (specifically, of secondary

polycythemia)

on September 26, 1945 at age 64. His funeral was attended by only ten

people, including his friend the pianist György

Sándor. Bartok's body was initially interred in Ferncliff

Cemetery in Hartsdale, New

York, but during the

final year of communist Hungary in the late 1980s, his remains were

transferred to Budapest for a state funeral on July 7, 1988 with

interment in Budapest's Farkasréti

Cemetery. He

left

his Third Piano Concerto almost finished at his death. For the

Viola Concerto he only left the viola part and sketches of the

orchestra part. Both works were later completed by his pupil, Tibor Serly.

György

Sándor was the soloist in the first performance of

the Third Piano Concerto on February 8, 1946. The Viola Concerto was

revised and polished in the 1990s by Bartók's son, Peter, and

this version may be closer to what Bartók may have intended. There

is a statue of Béla Bartók in Brussels, Belgium, near the central train station

in a public square, Spanjeplein-Place d'Espagne. Another statue stands

in London, opposite South Kensington Underground

Station. Still another is in front of one of the houses that

Bartók owned in the hills above Budapest, which is now a museum.