<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Jean Charles de Borda, 1733

- Instrument Maker Bartolomeo Cristofori di Francesco, 1655

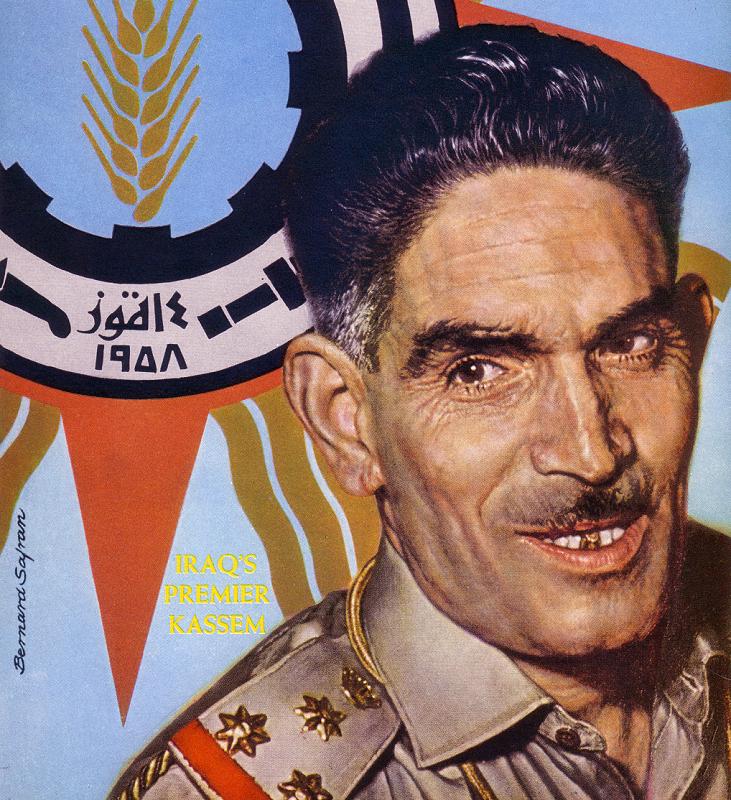

- Dictator of Iraq Abdul Karim Kassem, 1914

PAGE SPONSOR

Abd al-Karim Qasim (Arabic: عبد الكريم قاسم `Abd al-Karīm Qāsim) (1914 – February 9, 1963), was a nationalist Iraqi Army officer who seized power in a 1958 coup d'état, wherein the Iraqi monarchy was eliminated. He ruled the country as Prime Minister of Iraq until his downfall and death in 1963.

His name

can be transliterated from the Arabic in a number of ways, e.g.

Abdel Karim Kassem, Abdul Karim Kassem, Abdulkarim Kasem, Abdel-Karim

Qaasim, `Abdul Karim Qasem, Qassem. During his rule, he was popularly

known as al-za‘īm (الزعيم) or, "The Leader". Abd

al-Karim Qasim's father was a Sunni

Muslim of Arab descent who died shortly

after his son's birth during World

War

I as a soldier for the Ottoman

Empire. Qasim's mother was a Shiite and the daughter of a Feyli Kurd farmer from Baghdad. When

Qasim was six years of age his family moved to Suwayra, a small town

near the Tigris, then to Baghdad in 1926. Qasim was an excellent

student; he entered secondary school on a government scholarship. After graduation in 1931,

he taught at Shamiyya Elementary School from Oct 22 of that year until

Sept 3, 1932, when he was accepted into Military College. In 1934, he

graduated as a second lieutenant. Qasim then attended al-Arkan (Iraqi

Staff) College and graduated with honor (grade A) in December 1941. In

1951, he completed a senior officers’ course in Britain. Militarily,

he

participated in the suppression of the tribal disturbances in the

Middle Euphrates region in 1935, during the Anglo-Iraqi

War in May 1941 and

in the Kurdistan War in 1945. Qassim also served during the Iraqi

military involvement in the Arab-Israeli War from May 1948 to June

1949. Toward the latter part of the mission, he commanded a battalion

of the First Brigade, which was situated in the Kafr Qasem area south

of Qilqilya. In 1956 - 57, he served with his brigade at Mafraq in Jordan

in the wake of the Suez Crisis. By 1957 Qassim had assumed leadership of several opposition

groups that had formed in the army. On 14

July 1958, Qasim and his followers used troop movements planned by the

government as an opportunity to seize military control of Baghdad and overthrow the monarchy.

This resulted in the killing of several members of the royal family and

their close associates, including Nuri

as-Said. The coup

was discussed and planned by the Free

Officers, but was mainly executed by Qasim and Col. Abdasalaam

Arif. It was triggered when King Hussein, fearing that an

anti-Western revolt in Lebanon might spread to Jordan, requested Iraqi

assistance. Instead of moving towards Jordan, however, Colonel Arif led

a battalion into Baghdad and immediately proclaimed a new republic and

the end of the old regime. Put in its historical context, the 14

July

Revolution was

the culmination of a series of uprisings and coup attempts that began

with the 1936 Bakr

Sidqi coup and

included the 1941

Rashid

Ali military movement, the 1948 Wathbah Uprising, and the

1952 and 1956 protests. The July 14 Revolution met virtually no opposition. Prince Abdul

Ilah did not

want any resistance to the forces that besieged the Royal Rihab Palace,

hoping to gain permission to leave the country. The commander of the

Royal Guards battalion on duty, Col. Taha Bamirni, ordered the palace

guards to cease fire. On July

14, 1958, the royal family including King

Faisal

II; the Prince 'Abd

al-Ilah; Princess

Hiyam, Abdullah's wife; Princess

Nafisah, Abdullah’s mother, Princess

Abadiyah, the king’s aunt, and several servants were attacked as

they were leaving the palace. When all of them arrived in the courtyard

they were told to turn towards the palace wall, and were all shot down

by Captain Abdus Sattar As Sab’ a member of the coup led by Colonel Abd

al-Karim Qasim. King

Faisal II and Princess Hiyam were wounded. The King died later before

reaching the hospital. Princess Hiyam was not recognized at the

hospital and managed to receive treatment. Later she left for Saudi

Arabia where her family lived and then moved to Egypt until her death. In the

wake of the successful coup, the new Iraqi Republic was headed by a

Revolutionary Council.

At

its head was a three man sovereignty council, composed of members of

Iraq’s three main communal/ethnic groups. Muhammad

Mahdi

Kubbah represented the Shi’a population; Khalid

al-Naqshabandi the Kurds;

and Najib

al

Rubay’i the Sunni population.

This

tripartite was to assume the role of the Presidency. A cabinet was

created, composed of a broad spectrum of Iraqi political movements:

this included two National Democratic Party representatives, one member

of al-Istiqlal, one Ba’ath representative and one Marxist. After

seizing power, Qasim assumed the post of Prime Minister and Defense

Minister, while Colonel Arif was selected Deputy Prime Minister and

Interior Minister. They became the highest authority in Iraq with both

executive and legislative powers. Muhammad Najib

ar-Ruba'i became

chairman of the Sovereignty Council (head of state), but his power was

very limited. On July

26, 1958, the Interim Constitution was adopted, pending a permanent law

to be promulgated after a free referendum. According to the document,

Iraq was to be a republic and a part of the Arab nation whilst the

official state religion was listed as Islam. Powers

of legislation were vested in the Council of Ministers, with the

approval of the Sovereignty Council, whilst executive function was also

vested in the Council of Ministers. The consitiution proclaimed

the equality of all Iraqi citizens under the law and granting them

freedom without regard to race, nationality, language or religion. The

government freed political prisoners and granted amnesty to the Kurds

who participated in the 1943 to 1945 Kurdish uprisings. The exiled

Kurds returned home and were welcomed by the republican regime. Qasim was

Prime Minister from July 1958 - February 1963. Despite

the encouraging tones of the temporary constitution, the new government descended into an autocracy with

Qasim at its head. The

genesis of Qasim’s elevation to ‘Sole Leader’ began with a schism

between himself and his fellow conspirator Arif. Despite one of the

major goals of the revolution being to join the pan-Arabism movement

and practice qawmiyah policies, the corrupting influence of power soon

began to modify the views of Qasim. Qasim, reluctant to tie himself too

closely to Nasser’s Egypt - and warned by various groups within Iraq

(notably the communists) that

such an action would be dangerous - instead found himself echoing

the views of his predecessor, Said, by adopting a wataniyah policy of

‘Iraq First'. Unlike

the bulk of military officers, Qasim did not come from the Arab Sunni

northwestern towns nor did he share their enthusiasm for pan- Arabism:

he was of mixed Sunni-Shia parentage from southeastern Iraq. Qasim's

ability to remain in power depended, therefore, on a skillful balancing

of the communists and the pan-Arabists. For most of his tenure, Qasim

sought to counterbalance the growing pan-Arab trend in the army by

supporting the communists who controlled the streets. He authorized the

formation of a communist controlled militia, the People's Resistance

Force, and he freed all communist prisoners. Qasim

lifted a ban on the Iraqi

Communist Party, and demanded the annexation of Kuwait. He was also involved in the

1958 Agrarian Reform, modeled after the Egyptian experiment of 1952. Qasim is

said by his admirers to have worked to improve the position of ordinary

people in Iraq, after the long period of self-interested rule by a

small elite under the monarchy which had resulted in widespread social

unrest. Qasim passed law No. 80 which seized 99% of Iraqi land from the

British-owned Iraq Petroleum Company, and distributed farms to more of

the population. This increased the size of

the middle class. Qasim also oversaw the building of 35,000 residential

units to house the poor and lower middle

classes. The most notable example, and indeed symbol, of

this was the new suburb of Baghdad named Madinat al-Thawra (revolution

city), renamed Saddam City under the Baath regime and now widely

referred to as Sadr

City. Qasim rewrote the constitution to encourage women’s

participation in the society. Qasim

tried to maintain the political balance by using the traditional

opponents of pan-Arabs, the right

wing and nationalists.

Up

until the war with the Kurdish factions in the north he was able to

maintain the loyalty of the army. Despite a

shared military background, the group of Free Officers that carried out

the July 14 Revolution was plagued by internal dissension. Its members

lacked both a coherent ideology and an effective organizational

structure. Many of the more senior officers resented having to take

orders from Arif, their junior in rank. A power struggle developed

between Qasim and Arif over joining the Egyptian - Syrian

union. Arif's pro-Nasserite sympathies were supported

by the Baath

Party, while Qasim found support for his anti-unification position

in the ranks of the Iraqi

Communist

Party.

Qasim’s

change of policy aggravated his relationship with Arif. The latter,

despite being the subordinate of Qasim, had gained great prestige as

the perpetrator of the coup itself. Arif capitalised upon his newfound

position by partaking in a series of widely publicised public orations,

during which he strongly advocated union with the UAR, making numerous

positive references to Nasser, while remain noticeably less full of

praise for Qasim. Arif’s criticism of Qasim became gradually more

profound leading the latter to take steps to counter his potential

rivalry. Qasim began to foster relations with the Iraqi communist

party, who attempted to mobilise support in favour of his policies. He

also moved to counter Arif’s base of power by removing him from his

position as deputy commander of the armed forces. On

September 30 Qasim removed Arif’s status as Deputy Prime Minister and

as Minister of the Interior. Qasim

attempted to remove Arif’s disruptive influence by offering him a

role as Iraqi ambassador to West

Germany in Bonn.

Arif refused, and in a confrontation with Qasim on October 11, Arif is

reported to have drawn his pistol in the presence of Qasim; although

whether it was to assassinate Qasim or commit suicide is a source of

debate.

No

blood was shed, and Arif agreed to depart for Bonn. However his time

in Germany was brief, as he attempted to return to Baghdad on November

4 amid rumours of an attempted coup against Qasim. He was promptly

arrested, and charged on November 5 with attempted assassination of

Qasim and attempts to overthrow the regime.

He

was brought to trial for treason and condemned to death in January

1959; but was subsequently pardoned in December 1962 and was sentenced

to life imprisonment. Although

the threat of Arif had been negated, another soon arose in the form of Rashid

Ali, the exiled former Prime Minister who had fled Iraq in 1941.

Ali attempted to foster support amongst officers who were unhappy at

Qasim’s policy reversals. A coup was planned for December 9, but Qasim

was prepared, and instead had the conspirators arrested on the same

date. Ali was imprisoned and sentenced to death, although the execution

was never carried out. The new

Government declared Kurdistan “one of the two nations of Iraq.” During

his rule, the Kurdish groups selected Mustafa

Barzani to

negotiate with the government, seeking an opportunity to declare

independence. After a

period of relative calm, the issue of Kurdish autonomy (self-rule or

independence) went unfulfilled, sparking discontent and eventual

rebellion among the Kurds in 1961. Kurdish separatists under the

leadership of Mustafa Barzani chose to wage war against the Iraqi

establishment. Although relations between Qasim and the Kurds had

initially proved successful, relations had deteriorated by 1961, with

the Kurds becoming openly critical of Qasim’s regime. Barzani had

delivered an ultimatum to Qasim in August 1961 demanding an end to

authoritarian rule; recognition of Kurdish autonomy; and restoration of

democratic liberties.

Qasim’s

response was to sanction a military campaign against Barzani’s peshmerga forces

in September 1961.

This proved to be a grave mistake, as the anti-insurgency campaign

became a drain upon Iraqi resources as well as further undermining

Qasim’s esteem within the officer classes. During

Qasim's term, there was a much debate over whether Iraq should join the United

Arab

Republic, led by Gamal Abdel Nasser. Having dissolved the Arab

Union with the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, Qasim refused entry into

the federation, although his government recognized the republic and

considered joining it later. A major pan-Arabist concern was the repression

of the Iraqi branch of the Baath

Party. Qasim’s

growing ties with the communists served to provoke rebellion in the

northern Iraqi city of Mosul by Arab nationalists in charge of military

units. Qasim in an attempt to intimidate any potential coup had

encouraged a communist backed Peace Partisans rally in Mosul on March

6, 1959. Some 250,000 Peace Partisans and communists thronged Mosul’s

streets by March 6,

and

although the rally passed peacefully, on March 7, skirmishes broke

out amongst communists and nationalists. This degenerated into a

miniature civil war in the days following. Although the rebellion was

crushed by the military, it had a number of adverse effects that affected Qasim’s position. First, it increased the power of the

communists. Second, it encouraged the ideas of the Ba’ath

Party’s (which had

been steadily growing since the July 14 coup). The Ba’ath Party

believed that the only way of halting the engulfing tide of communism

was to assassinate Qasim. Such an attempt was carried out on October 7,

1959 by a group of Ba’athists, including a young Saddam

Hussein and reportedly supported by

the United

States. The assassination attempt

failed and led to a harsh crackdown on domestic opposition and the

development of a personality cult. The

growing influence of communism was felt throughout 1959. A communist

sponsored purge of the armed forces was carried out in the wake of the

Mosul revolt. The Iraqi cabinet began to shift towards the radical left

as several communist sympathisers gained posts in the cabinet. Iraq’s

foreign policy began to reflect this communist influence, as Qasim

removed Iraq from the Baghdad

Pact on March 24,

and later fostered closer ties with the USSR,

including

extensive economic agreements.

However

communist successes encouraged attempts to expand on their

position. The communists attempted to replicate their success at Mosul

in similar fashion at Kirkuk.

A

rally was called for July 14: intended to intimidate conservative

elements, it instead resulted in widespread bloodshed. Qasim

consequently cooled relations with the communists signaling a reduction

(although by no means a cessation) of their influence in the Iraqi

government. Qasim

soon withdrew Iraq from the pro-Western Baghdad Pact and established

friendly relations with the Soviet Union. Iraq also abolished its

Treaty of mutual security and bilateral relations with the UK. Also,

Iraq withdrew from the agreement with the United States that was signed

by the monarchy from 1954 to 1955 regarding military, arms, and equipment. On May 30, 1959, the last of the British soldiers and

military officers departed the al-Habbāniyya base in Iraq.

Qasim

supported the Algerian and Palestinian struggles against France and

Israel. However,

he further undermined his rapidly deteriorating position with a series

of foreign policy blunders. In 1959 Qasim antagonized Iran with a series of territory

disputes, most notably over the Arabic speaking Khuzistan region of Iran,

and

the division of the Shatt

al-Arab waterway

between south eastern Iraq and western Iran.

On

December 18, 1959, Abd al-Karim Qasim declared: "We do

not wish to refer to the history of Arab tribes residing in Al-Ahwaz

and Mohammareh [Khurramshahr]. The Ottomans handed over Muhammareh,

which was part of Iraqi territory, to Iran." After

this, Iraq started supporting secessionist movements in Khuzestan, and

even raised the issue of its territorial claims in the next meeting of

the Arab League, without any success. In June

1961, Qasim re-ignited the Iraqi claim over the state of Kuwait. On

June 19, Qasim announced in a press conference that Kuwait was a

part of Iraq, and claimed its territory. Kuwait, however, had signed a

recent defence treaty with the British, who came to her assistance with

troops to stave off any attack on July 1. This was subsequently

replaced by an Arab force (assembled by the Arab

League) in September, where they remained until 1962. The

result of Qasim’s foreign policy blunders was to further weaken his

position. Iraq was isolated from the Arab world for her part in the

Kuwait incident, whilst she had antagonised her powerful neighbour

Iran. Western attitudes towards Qasim had also cooled, due to these

incidents and his implied communist sympathies. Iraq was isolated

internationally, and Qasim became increasingly isolated domestically,

to his considerable detriment. Qasim’s

position was fatally weakened by 1962. His overthrow took place the

following year. The perpetrators were the Ba’ath

party, an Arab nationalist movement with a close knit structure and

ties within the military. The Ba’ath had initially benefited from the

1958 Revolution, gaining increased support in its wake. The group had

suffered after 1959 however due to the failure of the assassination

attempt upon Qasim. This weakened their membership when the

perpetrators were either imprisoned or exiled. The group also became disillusioned with Nasser after the establishment of

the UAR,

leading

to splits within the group. By 1962,

however, the Ba’ath was once again on the rise as a new group of

leaders under the tutelage of Ali

Salih

al-Sa’di began to re-invigorate the party. The Ba’ath Party

was now able to plot Qasim’s removal. Qasim was overthrown

by

the Ba'athist coup of February 8, 1963, motivated by fear of

communist influence and state control over the petroleum sector. This

coup has been reported to have been carried out with the backing of the

British government and the American CIA. Qasim

was

given a short trial and he was quickly shot. Later, footage of his

execution was broadcast to prove he was dead. At least

5,000 Iraqis were killed in the fighting from February 8–10, 1963, and

in the house-to-house hunt for "communists" that immediately followed.

Ba'athists put the losses of their own party at around 80. In July

2004, Qasim's body was discovered by a news team associated with Radio

Dijlah in Baghdad.

The

1958

Revolution can be heralded as a watershed in Iraqi politics, not

just because of its obvious political implications (e.g. the abolition

of monarchy, republicanism, and paving the way for Ba’athist rule) but

due to domestic reform. Despite its shortcomings, Qasim’s rule helped

to implement a number of positive domestic changes that benefitted

Iraqi society. The

revolution

brought about sweeping changes in the Iraqi agrarian sector.

Reformers dismantled the old feudal structure of rural Iraq:

for example the 1933 'Law of Rights and Duties of Cultivators' and the

Tribal Disputes Code were replaced, benefiting Iraq’s peasant

population and ensuring a fairer process of law. The Agrarian Reform

Law (September 30, 1958)

attempted

a large-scale redistribution of landholdings and placed ceilings on ground rents; the land was more evenly distributed amongst

peasants who, due to the new rent laws, received around 55% to 70% of

their crop.

Despite

the positive intentions of the Agrarian Reform Law, its

implementation proved relatively unsuccessful due to disagreements

between the lower classes and the landed middle classes, as well as a

time consuming implementation.

Qasim

attempted

to bring about greater equality for women in Iraq. In

December 1959 he promulgated a significant revision of the personal status code; particularly that regulating family relations. Polygamy was outlawed, and minimum

ages for marriage were also outlined, with 18 being the minimum age

(except for special dispensation when it could be lowered by the court

to 16).

Women

were also protected from arbitrary divorce. The most

revolutionary reform was a provision in article 74 giving women equal

rights in matters of inheritance.

The

laws applied to Sunni and Shi’a alike, yet despite their liberal

intent they received much opposition and did not survive Qasim’s

government. Education

was greatly expanded under the Qasim regime. The education budget was

raised from approximately 13 million Dinars in 1958 to 24 million Dinars

in 1960 and enrollment was increased. Attempts were also made in 1959

and 1961 to introduce economic planning to benefit social welfare;

investing in housing, healthcare and education, whilst reforming the

agrarian Iraqi economy along an industrial model. However these changes

were not truly implemented before Qasim’s removal. Qasim was

also responsible for the nationalisation of the Iraqi oil industry.

Public Law 80 dispossessed the IPC of 99.5% of its concession territory in Iraq and placed it in the hands of the newly formed Iraq

National

Oil Company taking

many of Iraq’s oilfields out of foreign hands.