<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Carl Gottfried Neumann, 1832

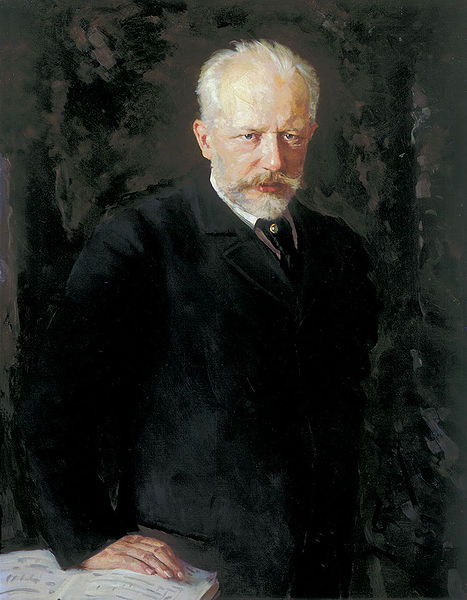

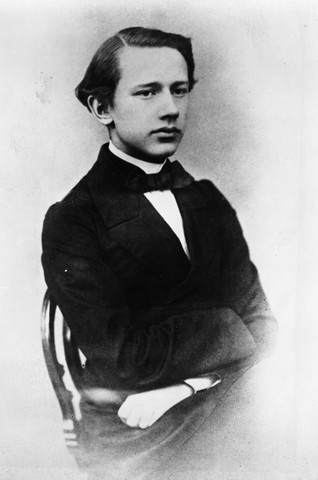

- Composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, 1840

- General of Cavalry Dagobert Sigmund von Wurmser, 1724

PAGE SPONSOR

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (Russian: Пётр Ильич Чайковский; often Peter Ilich Tchaikovsky in English; May 7, 1840 [O.S. April 25] – November 6, 1893 [O.S. October 25]) was a Russian composer of the Romantic era. His wide ranging output includes symphonies, operas, ballets, instrumental and chamber music and songs. He wrote some of the most popular concert and theatrical music in the classical repertoire, including the ballets Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty and The Nutcracker, the 1812 Overture, his First Piano Concerto, his last three numbered symphonies, and the opera Eugene Onegin.

Born into

a middle-class family, Tchaikovsky was educated for a career as a civil

servant, despite his obvious musical precocity. He pursued a musical

career against the wishes of his family, entering the Saint

Petersburg

Conservatory in

1862 and graduating in 1865. This formal, Western oriented training set

him apart from the contemporary nationalistic movement embodied by the

influential group of young Russian composers known as The

Five, with whom Tchaikovsky's professional relationship was mixed. Although

he enjoyed many popular successes, Tchaikovsky was never emotionally

secure, and his life was punctuated by personal crises and periods of

depression. Contributory factors were his suppressed homosexuality and fear of exposure, his

disastrous marriage, and the sudden collapse of the one enduring

relationship of his adult life, his 13-year association with the

wealthy widow Nadezhda von

Meck. Amid private turmoil Tchaikovsky's public reputation

grew; he was honored by the Tsar, awarded a lifetime pension and lauded

in the concert halls of the world. His sudden death at the age of 53 is

generally ascribed to cholera,

but

some attribute it to suicide. Although

perennially popular with concert audiences across the world,

Tchaikovsky's music was often dismissed by critics in the early and

mid 20th century as being vulgar and lacking in elevated thought. By the end of the 20th

century, however, Tchaikovsky's status as a significant composer was

generally regarded as secure. Pyotr

Ilyich Tchaikovsky was born in Votkinsk,

a

small town in present day Udmurtia,

formerly

province of Vyatka in the Russian

Empire, to a family with a long line of military service. Ilya

Petrovich Tchaikovsky, his father, was an engineer who served as a

lieutenant colonel in the Department of Mines and manager of the famed

Kamsko-Votkinsk Ironworks. The composer's mother,

Alexandra Andreyevna née d'Assier, 18 years her husband's

junior, was of partial French ancestry, and was the

second of Ilya's three wives. Tchaikovsky had four

brothers (Nikolai, Ippolit, and twins Anatoly and Modest),

and

a sister, Alexandra. He also had a half-sister Zinaida from his

father's first marriage. Tchaikovsky

was

particularly close to Alexandra and the twins. Anatoly later

established a prominent legal career, while Modest became a dramatist, librettist,

and

translator. Alexandra

married

Lev Davydov and had seven children, one

of whom, "Bob",

"[became]

a central figure in the composer's final years". The Davydovs provided the

only real family life Tchaikovsky knew as an adult, and their estate in

Kamenka, Ukraine, became a welcome refuge for him during his years of

wandering. In 1843,

due to the growth in family responsibilities, Tchaikovsky's

parents hired

a French governess, Fanny Dürbach, a 22 year old experienced

teacher who, Modest later wrote, "knew both French and German equally

well, and whose morals were strictly Protestant". While Dürbach had been

hired to look after Tchaikovsky's elder brother Nikolai and a

Tchaikovsky niece, it was not long before Tchaikovsky became curious

about the young woman and, as biographer Anthony

Holden wrote,

"wormed his way into Fanny Dürbach's affections, and thus into her

classes". Dürbach's love and

affection for her charge is said to have provided a counter to

Tchaikovsky's mother, who is described by Holden as a cold, unhappy,

distant parent not given to displays of physical affection. However, Tchaikovsky

scholar Alexander Poznansky wrote that the mother doted on her son. Tchaikovsky

began

piano lessons at the age of five. A precocious pupil, he could

read music as adeptly as his teacher within three years. His parents

were initially supportive of his musical talents, hiring a tutor,

buying an orchestrion (a form of barrel organ

that could imitate elaborate orchestral effects), and encouraging his

study of the piano. However, his parents'

passion for his musical talent soon cooled, and, in 1850, the family

decided to send Tchaikovsky to the Imperial

School

of Jurisprudence in Saint

Petersburg. The school mainly served the lesser nobility, and would

prepare him for a career as a civil servant. As the minimum age for

acceptance was 12, Tchaikovsky was required to spend two years boarding

at the Imperial School of Jurisprudence's preparatory school,

800 miles (1,300 km) from his family. Once those two years had

passed, Tchaikovsky transferred to the Imperial School of Jurisprudence

to begin a seven-year course of studies. On June

25, 1854 Tchaikovsky suffered the shock of his mother's death from cholera.

Tchaikovsky

authority David

Brown calls it "the crucial event of [Tchaikovsky's] years at the School of Jurisprudence", and noted that "it was

certainly shattering." Tchaikovsky bemoaned the

loss of his mother for the rest of his life, and admitted that it had

"a huge influence on the way things turned out for me." He was so affected that he

was unable to inform Fanny Dürbach until two years after the fact. At the age of 40,

approximately 26 years after his mother's death, Tchaikovsky wrote to

his patroness, Nadezhda

von

Meck, "Every moment of that appalling day is as vivid to me as

though it were yesterday." However,

within

a month of his mother's death he was making his first serious efforts at composition, a waltz in her memory.

Tchaikovsky's father, who also became sick with cholera at this time

but made a full recovery, immediately sent the boy back to school in

hope that the classwork would occupy his mind. To make up for his sense of

isolation and to compensate for the loss in his family, Tchaikovsky

formed important friendships with fellow students, such as those with Aleksey

Apukhtin and

Vladimir Gerard, which lasted the rest of his life. He

may

have also been exposed to the allegedly widespread homosexual practices at the school.

Whether these were formative experiences or practices toward which the

composer would have gravitated normally, biographers agree that he may

have discovered his sexual orientation at this time. Music was

not considered a high priority at the School of Jurisprudence, but Tchaikovsky maintained

a connection to music extracurricularly, by regularly attending the

theater and the opera with other students. At this time, he was fond

of works by Rossini, Bellini, Verdi and Mozart.

He

was known to sit at the school's harmonium after choir practice and

improvise on whatever themes had just been sung. "We were amused,"

Vladimir Gerard later remembered, "but not imbued with any expectations

of his future glory." Piano manufacturer Franz

Becker made occasional visits to the school as a token music teacher.

This was the only formal music instruction Tchaikovsky received there.

In 1855, Ilya Tchaikovsky funded private lessons with Rudolph

Kündinger, a well-known piano teacher from Nuremberg.

Ilya

also questioned Kündinger about a musical career for his son.

Kündinger replied that while he was impressed with Tchaikovsky's

ability to improvise at the keyboard, nothing suggested a potential

composer or even a fine performer. Tchaikovsky was told to finish his

course and then try for a post in the Ministry of Justice. On June

10, 1859, at the age of 19, Tchaikovsky graduated from the School of

Jurisprudence with the rank of titular counsellor, a low rank on the

civil service ladder. On June 15, he was appointed to the Ministry of

Justice. Six months later he became a junior assistant and two months

after that, a senior assistant, where he remained for the rest of his

three-year civil service career. In 1861,

Tchaikovsky attended classes in music

theory organized by

the Russian

Musical

Society (RMS)

and taught by Nikolai

Zaremba. A year later he followed Zaremba to the new Saint

Petersburg

Conservatory. Tchaikovsky decided not to give up his

Ministry post "until I am quite certain that I am destined to be a

musician rather than a civil servant." From 1862 to 1865 he studied harmony and counterpoint with Zaremba, while Anton

Rubinstein, director and founder of the Conservatory, taught him

instrumentation and composition. In 1863, Tchaikovsky

abandoned his civil service career and began studying music full-time,

graduating from the Conservatory in December 1865. Though Rubinstein

was impressed by Tchaikovsky's musical talent, he and Zaremba later

clashed with the young composer over his First

Symphony, written after his graduation, when he submitted it to

them for their perusal. The symphony was given its first complete

performance in Moscow in February 1868, where it was well received. Rubinstein's

Western

musical orientation brought him into opposition with the nationalistic group

of

musicians known as The

Five. As Tchaikovsky was Rubinstein's best-known pupil, he became a

target for the group, especially for César

Cui. Cui's criticisms began with

a blistering review of a cantata Tchaikovsky

had written as

his graduation exercise from the Conservatory. Calling the piece

"feeble", Cui wrote that if Tchaikovsky had any gift for music, "then

at least somewhere or other [the cantata] would have broken through the

fetters of the Conservatoire". The effect of this review

on Tchaikovsky was devastating: "My vision grew dark, my head spun, and

I ran out of the café like a madman.... All day I wandered

aimlessly through the city, repeating, 'I'm sterile, insignificant, nothing will come out of me, I'm ungifted'". When in

1867, Rubinstein resigned as conductor from Saint Petersburg's Russian

Musical

Society orchestra,

he was replaced by composer Mily

Balakirev, leader of The Five. Tchaikovsky, now Professor of Music

Theory at the Moscow

Conservatory, had already promised his Dances of the Hay Maidens (which he later included in

his opera The

Voyevoda, as Characteristic

Dances) to the society. In submitting the manuscript (and perhaps

mindful of Cui's review of the graduation cantata), Tchaikovsky

included a note to Balakirev that ended with a request for a word of

encouragement should the Dances not be performed. Possibly

sensing

a new disciple in Tchaikovsky, Balakirev wrote "with

complete frankness" in his reply that he felt that Tchaikovsky was "a

fully fledged artist". These letters set the tone

for Tchaikovsky's relationship with Balakirev over the next two years.

In 1869, the two entered into a working relationship, the result being

Tchaikovsky's first recognised masterpiece, the fantasy-overture Romeo

and

Juliet, a work which The Five wholeheartedly embraced. Though,

personally, Tchaikovsky remained on friendly terms with most of The

Five, professionally, he was usually ambivalent about their music. Despite the collaboration

with Balakirev on the Romeo

and

Juliet fantasy-overture,

Tchaikovsky

made considerable efforts to ensure his musical

independence from the group as well as from the conservative faction at

the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. From 1867

to 1878, Tchaikovsky combined his professorial duties with music

criticism while

continuing to compose. Some of his best known works from this period include the First

Piano

Concerto, the Variations

on

a Rococo Theme for violoncello and orchestra, the Little

Russian and Fourth

Symphonies, the ballet Swan

Lake and the

opera Eugene

Onegin. The First Piano Concerto suffered an initial rejection

by its intended dedicatee, Anton Rubinstein's brother Nikolai,

though

he eventually championed the work. The work was subsequently

premiered in Boston in October 1875, played by Hans

von

Bülow, whose pianism had impressed Tchaikovsky during an

appearance in Moscow in March 1874. In

Moscow, teaching with Nikolai Rubinstein, Tchaikovsky gained his first

taste of famed appreciation. Introduced into the Artistic Circle, a

club founded by Rubinstein, Tchaikovsky enjoyed a sense of social

celebrity status among friends and fellow artists. However, over a five year

period, Tchaikovsky became frustrated with teaching and found himself

struggling financially. He gradually moved away from Rubinstein, to

maintain his independence from Rubinstein's renowned reputation. Nevertheless, while the

move to Moscow was bittersweet, filled with friendship, jealousy, and

inner struggles, it was successful from a

professional point of view. Tchaikovsky's musical works were frequently

performed, with few delays between their composition and first

performances, and the publication (after 1867) of songs and piano music

for the home market helped bolster the composer's popularity. In his

book, Tchaikovsky:

The Quest for the Inner Man, Poznansky showed that Tchaikovsky had

homosexual tendencies and that some of the composer's closest

relationships were with persons of the same sex. Tchaikovsky's servant

Aleksei Sofronov and the composer's nephew, Vladimir

"Bob"

Davydov, have been speculated as possible romantic interests. Tchaikovsky

dedicated

his Sixth Symphony, the Pathétique,

to

Davydov. The love theme from Romeo

and

Juliet is

generally considered to have been inspired by Eduard Zak. More

controversial than Tchaikovsky's reported sexual proclivities is how

comfortable the composer might have been with his sexual nature. After

reading all Tchaikovsky's letters (including unpublished ones),

Poznansky concludes that the composer "eventually came to see his

sexual peculiarities as an insurmountable and even natural part of his

personality ... without experiencing any serious psychological

damage." Relevant portions of his

brother Modest's autobiography, where he tells of his brother's sexual

orientation, have also been published. Modest, like Tchaikovsky,

was homosexual. Some letters previously

suppressed by Soviet censors, where Tchaikovsky openly speaks out about

his homosexuality, have been published in Russian, as well as by

Poznansky in English translation. However, biographer Anthony

Holden claims

British musicologist and scholar Henry Zajaczkowski's research "along

psychoanalytical lines" points instead to "a severe unconscious

inhibition by the composer of his sexual feelings": One

consequence of it may be sexual overindulgence as a kind of false

solution: the individual thereby persuades himself that he does accept

his sexual impulses. Complementing this and, also, as a psychological

defense mechanism, would be precisely the idolization by Tchaikovsky of

many of the young men of his circle [the self-styled "Fourth Suite"],

to which Poznansky himself draws attention. If the composer's response

to possible sexual objects was either to use and discard them or to

idolize them, it shows that he was unable to form an integrated, secure

relationship with another man. That, surely, was [Tchaikovsky's]

tragedy. Musicologist

and

historian Roland John Wiley suggests a third alternative, based on

Tchaikovsky's letters. He suggests that while Tchaikovsky experienced

"no unbearable guilt" over his homosexuality, he remained aware of the

negative consequences of that knowledge becoming public, especially of

the ramifications for his family. His decision to enter into

a heterosexual union and try to lead a double life was prompted by

several factors — the possibility of exposure, the willingness to please

his father, his own desire for a permanent home and his love of

children and family. While Tchaikovsky may have

been romantically active, the evidence for "sexual argot and passionate

encounter" is limited. He sought out the company

of homosexuals in his circle for extended periods, "associating openly

and establishing professional connections with them." Wiley adds, "Amateurish

criticism to the contrary, there is no warrant to assume, this period

[of his short lived marriage] excepted, that Tchaikovsky's sexuality

ever deeply impaired his inspiration, or made his music

idiosyncratically confessional or incapable of philosophical utterance." Professor Robert Greenberg

of the San Francisco Conservatory of Music agrees, describes his turn

towards a troubled inner world where he, “found a world of

self-expression that he might never have discovered had he felt less

alienated from society.” In 1868,

at the age of 28, Tchaikovsky met the Belgian soprano Désirée

Artôt, then on a tour of Russia. They became infatuated, and were engaged to be married. He dedicated his Romance in F minor for piano, Op. 5, to her.

However, on September 15, 1869, without any communication with

Tchaikovsky, Artôt married a member of her company, the Spanish

baritone Mariano

Padilla

y Ramos. The general view has been that Tchaikovsky got

over the affair fairly quickly. It has, however, been postulated that

he coded her name into the Piano

Concerto

No. 1 in B-flat minor and

the

tone-poem Fatum. They

met

on a handful of later occasions, and in October 1888 he wrote Six French Songs,

Op. 65, for her, in response to her request for a single song.

Tchaikovsky later claimed she was the only woman he ever loved. In April

1877 Tchaikovsky's favorite pupil, Vladimir Shilovsky, married suddenly. Shilovsky's wedding may in

turn have spurred Tchaikovsky to consider such a step himself. He declared his intention

to marry in a letter to his brother. There

followed

Tchaikovsky's ill-starred marriage to one of his former

composition students, Antonina

Miliukova. The brief time with his wife drove him to an emotional

crisis, which was followed by a stay in Clarens,

Switzerland, for rest and recovery. They

remained

legally married but never lived together again nor had any

children, though she later gave birth to three children by another man. Tchaikovsky's

marital

debacle may have forced him to face the full truth concerning

his sexuality. He apparently never again

considered matrimony as a camouflage or escape, nor considered himself

capable of loving women in the same manner as men. He wrote to his brother

Anatoly from Florence, Italy on February 19, 1878, Thanks

to the regularity of my life, to the sometimes tedious but always

inviolable calm, and above all, thanks to time which heals all wounds,

I have completely recovered from my insanity.

There's

no doubt that for some months on end I was a bit insane, and only

now, when I'm completely recovered, have I learned to relate objectively to everything which I did

during my brief insanity. That man who in May took it into his head to

marry Antonina Ivanova, who during June wrote a whole opera as though

nothing had happened, who in July married, who in September fled from

his wife, who in November railed at Rome and so on — that man wasn't I,

but another Pyotr Ilyich. A few

days later, in another letter to Anatoly, he added that there was

"nothing more futile than wanting to be anything other than what I am

by nature." It

has

been commonly held that the strain of the marriage and Tchaikovsky's

emotional state immediately preceding it may have enhanced

Tchaikovsky's creativity. To some extent, this may have been the case.

While the Fourth

Symphony was begun

some months before Tchaikovsky married Antonina, both the symphony and the

opera Eugene

Onegin, arguably two of his finest compositions, are held up as proof of

this enhanced creativity. He finished both these

works in the six months between his engagement and the completion of

the rest cure following his marriage breakdown. While in Clarens he

also composed his Violin

Concerto, with the technical assistance of one of his former

students, violinist Yosif Kotek. Kotek later helped establish contact

between Tchaikovsky and Nadezhda von Meck, the widow of a railway

magnate, who became the composer's patron and confidante. Like the

First Piano Concerto, the Violin Concerto was rejected initially by its

intended dedicatee, virtuoso and pedagogue Leopold

Auer, and was premiered by Adolph

Brodsky. While the work eventually achieved public success, the

audience hissed at its premiere in Vienna, and it was denigrated by

music critic Eduard

Hanslick: The

Russian composer Tchaikovsky is surely no ordinary talent, but rather,

an inflated one, obsessed with posturing as a man of genius, and

lacking all discrimination and taste ... the same can be said for

his new, long, and ambitious Violin Concerto. For a while it proceeds

soberly, musically, and not mindlessly, but soon vulgarity gains the

upper hand and dominates until the end of the first movement. The

violin is no longer played: it is tugged about, torn, beaten black and

blue ... The Adagio is well on the way to reconciling us and winning us

over when, all too soon, it breaks off to make way for a finale that

transports us to the brutal and wretched jollity of a Russian church

festival. We see a host of gross and savage faces, hear crude curses,

and smell the booze. In the course of a discussion of obscener

illustrations, Friedrich

Vischer once

maintained that there were pictures whose stink one could see.

Tchaikovsky's Violin Concerto confronts us for the first time with the

hideous idea that there may be musical compositions whose stink one can

hear. Auer

belatedly accepted the concerto, and eventually played it to great

public success. In future years he taught the work to his pupils, including Jascha

Heifetz and Nathan

Milstein. Auer later said about Hanslick's comment that "the last

movement was redolent of vodka [...] did credit neither to his good

judgment nor to his reputation as a critic." The

intensity of personal emotion now flowing through Tchaikovsky's works

was entirely new to Russian music. It prompted some Russian commentators to place his name alongside that of novelist Fyodor

Dostoyevsky. Like Dostoyevsky's

characters, they felt the musical hero in Tchaikovsky's music persisted

in exploring the meaning of life while trapped in a fatal

love-death-faith triangle. The critic Osoovski wrote

of Tchaikovsky and Dostoyevsky: "With a hidden passion they both stop

at moments of horror, total spiritual collapse, and finding acute

sweetness in the cold trepidation of the heart before the abyss, they

both force the reader to experience those feelings, too." Tchaikovsky's

fame

among concert audiences began to expand outside Russia, and

continued to grow within it. Hans von Bülow had become a fervent

champion of the composer's work after hearing some of it in a Moscow

concert during Lent of 1874. In a German newspaper later

that year, he praised the First

String

Quartet, Romeo

and Juliet and

other works, and he later took up many other Tchaikovsky works both as

pianist and conductor. In France, Camille Benoit

began introducing Tchaikovsky's music to readers of the Revue et gazette

musicale de Paris. The music also received significant exposure

during the 1878 International Exhibition in Paris. While Tchaikovsky's

reputation as a composer grew, a corresponding increase in performances

of his works did not occur until he began conducting them himself,

starting in the mid 1880s. Nevertheless,

by

1880, all of the operas Tchaikovsky had completed up that point had

been staged, and his orchestral works had been given performances that

had been sympathetically received. Nadezhda

von Meck was the wealthy widow of a Russian railway tycoon and an

influential patron of the arts. Having already heard some of

Tchaikovsky's work, she was encouraged by Kotek to commission some

chamber pieces from him. Her support became an important element in Tchaikovsky's life; she eventually paid him an

annual subsidy of 6,000 rubles,

which

made it possible for him to resign from the Moscow Conservatory

in October 1878 at the age of 38, and concentrate on composition. With von Meck's patronage came a relationship that, at her insistence, was mainly epistolary –

she stipulated they were never to meet face to face. They exchanged

well over 1,000 letters between 1877 and 1890. In these letters

Tchaikovsky was more open about much of his life and his creative

processes than he had been to any other person. As well

as being a dedicated supporter of Tchaikovsky's musical works, Nadezhda

von Meck became a vital enabler in his day-to-day existence by her

financial support and friendship. As he explained to her, There

is something so special about our relationship that it often stops me

in my tracks with amazement. I have told you more than once, I believe,

that you have come to seem to me the hand of Fate itself, watching over

me and protecting me. The very fact that I do not know you personally,

while feeling so close to you, accords you in my eyes the special

status of an unseen but benevolent presence, like a benign Providence. In 1884

Tchaikovsky and von Meck became related by marriage when one of her

sons, Nikolay, married Tchaikovsky's niece Anna Davydova. However, in 1890 she

suddenly ended her relationship with the composer. She was suffering

from health problems that made writing difficult; there were family

pressures, and also financial difficulties arising from the

mismanagement of her estate by her son Vladimir. The break with Tchaikovsky

was announced in a letter delivered by a trusted servant, rather than

by the usual postal service. It contained a request that he not forget

her, and was accompanied by a year's subsidy in advance. She claimed

bankruptcy, which, if not literally true, was evidently a real threat

at the time. Tchaikovsky

may

have been aware for nearly a year of his patroness's financial

difficulties. This did not stop him from

continuing to take his allowance for granted (with regular

protestations of his eternal gratitude), nor did he offer to return the

advance he received with the farewell letter. Despite his growing

celebrity throughout Europe, von Meck's allowance still made up a third

of the composer's income. While he may have no longer

needed her money as much as in the past, the loss of her friendship and

encouragement was devastating; he remained bewildered and resentful

about her abrupt disappearance for the remaining three years of his

life. Tchaikovsky

returned

to Moscow Conservatory in the autumn of 1879, having been away

from Russia for a year after the disintegration of his marriage.

However, he quickly resigned, settling in Kamenka yet traveling

incessantly. During these years, assured of a regular income from Nadezhda von Meck, he wandered around Europe

and rural Russia, never staying long in any one place and living mainly

alone, avoiding social contact whenever possible. This may have been due in

part to troubles with Antonina, who alternately agreed to, then

refused, divorce, at one point exacerbating matters by moving into an

apartment directly above her husband's. Tchaikovsky listed

Antonina's accusations to him in detail to Modest: "I am a deceiver who

married her in order to hide my true nature ... I insulted her

every day, her sufferings at my hands were great ... she is

appalled by my shameful vice, etc., etc." It is possible that he lived

the rest of his life in dread of Antonina's power to expose publicly

his sexual leanings. These factors may explain why, except for the piano

trio which he wrote

upon the death of Nikolai Rubinstein, his best work from this period is

found in genres which did not depend heavily on personal expression. While

Tchaikovsky's reputation grew rapidly outside Russia, it was, as Alexandre

Benois wrote in his memoirs, "considered obligatory [in progressive

musical circles in Russia] to treat Tchaikovsky as a renegade, a master

overly dependent on the West." In 1880 this assessment

changed, practically overnight. During commemoration ceremonies for the

Pushkin Monument in Moscow, Dostoyevsky charged that Alexander

Pushkin had given a

prophetic call to Russia for "universal unity" with the West. An unprecedented acclaim

for Dostoyevsky's message spread throughout Russia, and disdain for

Tchaikovsky's music dissipated. He even drew a cult following among the

young intelligentsia of St. Petersburg,

including Benois, Léon

Bakst and Sergei

Diaghilev. In 1880

the Cathedral

of

Christ the Saviour, commissioned by Tsar Alexander

I to commemorate

the defeat of Napoleon in 1812, was nearing completion in Moscow; the

25th anniversary of the coronation of Alexander

II in 1881 was

imminent; and

the

1882 Moscow Arts and Industry Exhibition was in the planning stage.

Nikolai Rubinstein suggested a grand commemorative piece for use in

related festivities. Tchaikovsky began the project in October 1880,

finishing it within six weeks. He wrote to Nadezhda von Meck that the

resulting work, the 1812

Overture, would be "very loud and noisy, but I wrote it with no

warm feeling of love, and therefore there will probably be no artistic

merits in it." He also warned conductor Eduard

Nápravník that

"I

shan't be at all surprised and offended if you find that it is in a

style unsuitable for symphony concerts." Nevertheless, this work has

become for many, as Tchaikovsky authority Professor

David

Brown phrased

it, "the piece by Tchaikovsky they know best." On March

23, 1881, Nikolai Rubinstein died in Paris.

Tchaikovsky

was holidaying in Rome,

and

he went immediately to attend the funeral in Paris for his greatly

respected mentor, but arrived too late (although he was part of a group

of people who saw Rubinstein's coffin off on a train back to Russia). In December, he started

work on his Piano

Trio

in A minor, "dedicated to the memory of a great artist." The trio was first

performed privately at the Moscow Conservatory, where Rubinstein had

been director, on the first anniversary of his death by three of its

staff — pianist Sergei

Taneyev, violinist Jan

Hřímalý and

cellist Wilhelm

Fitzenhagen. The piece became extremely

popular during the composer's lifetime and, in an ironic twist of fate,

became Tchaikovsky's own elegy when played at memorial

concerts in Moscow and St. Petersburg in November 1893.

During

1884,

now 44 years old, Tchaikovsky began to shed his unsociability and

restlessness. In March of that year Tsar Alexander III conferred upon

him the Order

of

St. Vladimir (fourth

class),

which carried with it hereditary

nobility and won Tchaikovsky a

personal audience with the Tsar. The Tsar's decoration was a

visible seal of official approval, that helped Tchaikovsky's social

rehabilitation. This rehabilitation may

have been cemented in the composer's mind with the extreme success of his Third

Orchestral

Suite at

its January 1885 premiere in Saint Petersburg, under Hans

von

Bülow's direction. Tchaikovsky

wrote

to Nadezhda von Meck: "I have never seen such a triumph. I saw

the whole audience was moved, and grateful to me. These moments are the

finest adornments of an artist's life. Thanks to these it is worth

living and laboring." The

press

was likewise unanimously favorable. In 1885,

after Tchaikovsky resettled in Russia, the Tsar asked personally for a

new production of Eugene

Onegin to be

staged in Saint Petersburg. The opera had previously been seen only in

Moscow, produced by a student ensemble from the Conservatory. Though critical reception to the Saint Petersburg production of Onegin was negative, the opera

drew full houses every night; 15 years later the composer's brother

Modest identified this as the moment Tchaikovsky became known and

appreciated by the masses, and he achieved the greatest degree of

popularity ever accorded to a Russian composer. News of the opera's

success spread, and the work was produced by opera houses throughout

Russia and abroad. A feature

of the Saint Petersburg production of Onegin was that Alexander III

requested that the opera be staged not at the Mariyinsky

Theater but at the Bolshoi

Kamennïy

Theater. This served notice that Tchaikovsky's music

was replacing Italian

opera as the

official imperial art. In addition, thanks to Ivan Vsevolozhsky, Director of the Imperial Theaters and a patron of the

composer, Tchaikovsky was awarded a lifetime pension of 3,000 rubles

per year from the Tsar. This essentially made him the premier court

composer, in practice if not in actual title. While he

still felt a disdain for public life, Tchaikovsky now participated in

it for two reasons — his increasing celebrity and what he felt was his

duty to promote Russian music. To

this end, he helped

support his former pupil Taneyev, who was now director of Moscow

Conservatory, by attending student examinations and negotiating the

sometimes sensitive relations among various members of the staff. Tchaikovsky also served as

director of the Moscow branch of the Russian Musical Society during the

1889 - 1890 season. In this post, he invited a number of international

celebrities to conduct, including Johannes

Brahms, Antonín

Dvořák and Jules

Massenet. Another

area in which Tchaikovsky promoted Russian music in general as well as

his own compositions was as a guest conductor. In January 1887 he

substituted at the Bolshoi

Theater in Moscow

on short notice for the first three performances of his opera Cherevichki. He had wanted to conquer

conducting for at least a decade, as he saw that success outside Russia

depended to some extent on his conducting his own works. Within a year of the Cherevichki performances,

Tchaikovsky

was in considerable demand throughout Europe and Russia,

which helped him overcome a life-long stage

fright and boosted

his self-assurance. Conducting brought him to

America in 1891, where he led the New

York

Music Society's orchestra in his Festival Coronation March at the inaugural concert of New

York's Carnegie

Hall. In 1888

Tchaikovsky led the premiere of his Fifth

Symphony in Saint

Petersburg, repeating the work a week later with the first performance of his tone poem Hamlet.

While

both works were received with extreme enthusiasm by audiences,

critics proved hostile, with César

Cui calling the

symphony "routine" and "meretricious." Undeterred, Tchaikovsky

continued to conduct the symphony in Russia and Europe. In

November 1887, Tchaikovsky arrived in Saint Petersburg in time to hear

several of the Russian

Symphony

Concerts, which were devoted exclusively to the music of

Russian composers. One of these concerts included the first complete

performance of the final version of his First

Symphony; another featured the premiere of the revised version of

Rimsky-Korsakov's Third Symphony. Before this visit

Tchaikovsky had spent much time keeping in touch with Rimsky-Korsakov

and those around him. Rimsky-Korsakov, along with Alexander

Glazunov, Anatoly

Lyadov and several

other nationalistically minded composers and musicians, had formed a

group called the Belyayev

circle. This group was named after timber merchant Mitrofan

Belyayev, an amateur musician who became a influential music patron

and publisher after he had taken an interest in Glazunov's work. (Belyayev

also

funded the Russian Symphony Concerts as a forum for native

composers to have their works heard in public.) During Tchaikovsky's visit,

he spent much time in the company of Glazunov, Lyadov and

Rimsky-Korsakov, and the somewhat fraught relationship he had endured

with the Belyayev circle's predecessor, The Five, melded into something

more harmonious. This relationship lasted until Tchaikovsky's death in

late 1893. A side

benefit of Tchaikovsky's friendship with Glazunov, Lyadov and

Rimsky-Korsakov was an increased confidence in his own abilities as a

composer, along with a willingness to let his musical works stand

alongside those of his contemporaries. Tchaikovsky wrote to Nadezhda

von Meck in January 1889, after being once again well-represented in

Belyayev's concerts, that he had "always tried to place myself outside all

parties and to show in

every way possible that I love and respect every honorable and gifted

public figure in music, whatever his tendency", and that he considered

himself "flattered to appear on the concert platform" beside composers

in the Belyayev circle. This was an acknowledgment

of wholehearted readiness for his music to be heard with that of these

composers, delivered in a tone of implicit confidence that there were

no comparisons from which to fear. In 1892,

Tchaikovsky was voted a member of the Académie

des

Beaux-Arts in

France; he was only the second Russian, after the sculptor Mark

Antokolsky, to be so honored. The following year, the University

of

Cambridge in

Britain awarded Tchaikovsky an honorary Doctor

of

Music degree. Tchaikovsky

died

in Saint Petersburg on November 6, 1893, nine days after the

premiere of his Sixth

Symphony, the Pathétique. Though only 53 years old, he

lived a long life compared to many 19th century composers. He was

interred in Tikhvin

Cemetery at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery, near the graves of fellow composers Alexander

Borodin, Mikhail

Glinka, Nikolai

Rimsky-Korsakov, Mily Balakirev and Modest

Mussorgsky. Because of the Pathétique's formal innovation and the

overwhelming emotional content of its outer movements, the work was

received by the public with silent incomprehension at its first

performance. The second performance, led

by Nápravník, took place 20 days later at a memorial

concert and was much more favorably

received. The Pathétique has since become one of

Tchaikovsky's best known works. Tchaikovsky's

death

has traditionally been attributed to cholera,

most

probably contracted through drinking contaminated water several days earlier. However, some, including

English musicologist and Tchaikovsky authority David

Brown and biographer Anthony

Holden,

have theorized that his death was a suicide. According to

one variation of the theory, a sentence of suicide was imposed in a

"court of honor" by Tchaikovsky's fellow alumni of the St. Petersburg

Imperial School of Jurisprudence, as a censure of the composer's

homosexuality. This unproven theory was first broached publicly by

Russian musicologist Alexandra Orlova in 1979, when she emigrated to

the West. Wiley writes in the New Grove (2001), "The polemics over

[Tchaikovsky's] death have reached an impasse ... Rumor attached to the

famous die hard ... As for illness, problems of evidence offer little

hope of satisfactory resolution: the state of diagnosis; the confusion

of witnesses; disregard of long-term effects of smoking and alcohol. We

do not know how Tchaikovsky died. We may never find out ..."