<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Rudolf Otto Sigismund Lipschitz, 1832

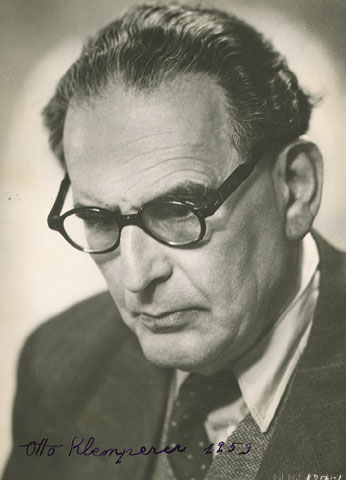

- Composer Otto Klemperer, 1885

- Minister President of Bavaria Kurt Eisner, 1867

PAGE SPONSOR

Otto Klemperer (14 May 1885, Breslau – 6 July 1973, Zürich) was a German-born conductor and composer. He is widely regarded as one of the leading conductors of the 20th century.

Otto Klemperer was born in Breslau, Silesia, then in Germany (now Wrocław, Poland). Klemperer studied music first at the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt, and later in Berlin under Hans Pfitzner. In 1905 he met Gustav Mahler while conducting the off-stage brass at a performance of Mahler's Symphony No. 2, 'Resurrection'. The two men became friends, and Klemperer became conductor at the German Opera in Prague in 1907 on Mahler's recommendation. Mahler wrote a short testimonial, recommending Klemperer, on a small card which Klemperer kept for the rest of his life. Later, in 1910, Klemperer assisted Mahler in the premiere of his Symphony No. 8, Symphony of a Thousand.

Klemperer went on to hold a number of positions, in Hamburg (1910 - 1912); in Barmen (1912 - 1913); the Strasbourg Opera (1914 - 1917); the Cologne Opera (1917 - 1924); and the State Opera in Wiesbaden (1924 - 1927). From 1927 to 1931, he was conductor at the Kroll Opera in Berlin. In this post he enhanced his reputation as a champion of new music, playing a number of new works, including Leoš Janáček's From the House of the Dead, Arnold Schönberg's Erwartung, Igor Stravinsky's Oedipus Rex, and Paul Hindemith's Cardillac.

In 1933, once the Nazi Party had reached power, Klemperer, who was Jewish, left Germany and moved to the United States. Klemperer had previously converted to Catholicism, but eventually returned to Judaism. In the U.S. he was appointed Music Director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra. He took United States citizenship in 1937. In Los Angeles, he began to concentrate more on the standard works of the Germanic repertoire that would later bring him greatest acclaim, particularly the works of Beethoven, Brahms and Mahler, though he gave the Los Angeles premieres of some of fellow Los Angeles resident Arnold Schoenberg's works with the Philharmonic. He also visited other countries, including England and Australia. While the orchestra responded well to his leadership, Klemperer had a difficult time adjusting to Southern California, a situation exacerbated by repeated manic depressive episodes, reportedly as a result of severe cyclothymic bipolar disorder.

Then, after completing the 1939 Los Angeles Philharmonic summer season at the Hollywood Bowl, Klemperer was visiting Boston and was incorrectly diagnosed with a brain tumor, and the subsequent brain surgery left him partially paralyzed. He went into a depressive state and was placed in institution; when he escaped, The New York Times ran a cover story declaring him missing, and after being found in New Jersey, a picture of him behind bars was printed in the Herald Tribune. Though he would occasionally conduct the Philharmonic after that, he lost the post of Music Director. Furthermore, his erratic behavior during manic episodes made him an undesirable guest to US orchestras, and the late flowering of his career centered in other countries.

Following the end of World War II, Klemperer returned to Continental Europe to work at the Budapest Opera (1947 - 1950). Finding Communist rule in Hungary increasingly irksome, he became an itinerant conductor, guest conducting the Royal Danish Orchestra, Montreal Symphony Orchestra, WDR Orchestra Köln, Concertgebouw Orchestra, and the Philharmonia of London. His career was turned around in 1954 by the London-based producer Walter Legge, who recorded Klemperer in Beethoven, Brahms and much else with his hand-picked orchestra, the Philharmonia, for the EMI label. He became the first principal conductor of the Philharmonia in 1959. He settled in Switzerland. Klemperer also worked at the Royal Opera House Covent Garden, sometimes stage-directing as well as conducting, as in a 1963 production of Richard Wagner's Lohengrin.

Klemperer is less well known as a composer, but he wrote a number of pieces, including six symphonies, a Mass, nine string quartets, many Lieder and the opera Das Ziel. He seldom performed any of these himself and they have generally fallen into neglect since his death, although Klemperer's works have received the occasional commercial recording.

A severe fall during a visit to Montreal forced Klemperer subsequently to conduct seated in a chair. A severe burning accident further paralyzed him, which resulted from his smoking in bed and trying to douse the flames with a glass of whisky. Through Klemperer's problems with his health, the tireless and unwavering support and assistance of Klemperer's daughter Lotte was crucial to his success. His son, Werner Klemperer, was an actor and became known for his portrayal of Colonel Klink on the US television show Hogan's Heroes. The diarist Victor Klemperer was a cousin; so were Georg Klemperer and Felix Klemperer, who were famous physicians.

Klemperer

took Israeli citizenship in 1970. He

retired from conducting in 1971. Klemperer died in Zürich,

Switzerland

in 1973, aged 88, and was buried in Zurich's Israelitischer

Friedhof-Oberer Friesenberg. He was an

Honorary Member (HonRAM) of the Royal

Academy of Music, which now houses his personal archive. Many

listeners associate Klemperer with slow tempos, but recorded evidence

now available on compact disc shows that in earlier years his tempi

could be quite a bit faster; the late recordings give a misleading

impression. For example, one of Klemperer's most noted performances was

of Beethoven's Symphony

No.

3, the Eroica.

Eric

Grunin's Eroica

Project contains

tempo data on 363 recordings of the work from 1924 - 2007, and includes

10 by Klemperer - some recorded in the studio, most from broadcasts of

live concerts. The earliest Klemperer performance on tape was recorded

in concert in Köln in 1954 (when he was 69

years old); the last was in London with the New

Philharmonia Orchestra

in

1970 (when he was 85). The passing years show a clear trend with

respect to tempo: as Klemperer aged, he took slower tempi. In 1954, his

first movement lasts 15:18 from beginning to end; in 1970 it lasts

18:41. In 1954 the main tempo of the first movement was about 135 beats

per minute, in 1970 it had slowed to about 110 beats per minute. In

1954, the Eroica second movement, "Funeral

March", had a timing of 14:35; in 1970, it had slowed to 18:51. Similar

slowings took place in the other movements. Around 1954, Herbert

von

Karajan flew especially to hear Klemperer conduct a performance of the Eroica,

and later he said to him: "I have come only to thank you, and say that

I hope I shall live to conduct the Funeral March as well as

you have done". Similar,

if less extreme, reductions in tempi can be noted in many other works

for which Klemperer left multiple recordings, at least in recordings

from when he was in his late 70s and his 80s. Regardless

of

tempo, Klemperer's performances often maintain great intensity. Eric

Grunin, in a commentary on the "opinions" page of his Eroica Project,

notes: "....The massiveness of the first movement of the Eroica is real, but is not its

main claim on our attention. That honor goes to its astonishing story

(structure), and what is to me most unique about Klemperer is that his

understanding of the structure remains unchanged no matter what his

tempo... "