<Back to Index>

- Physician Willem Einthoven, 1860

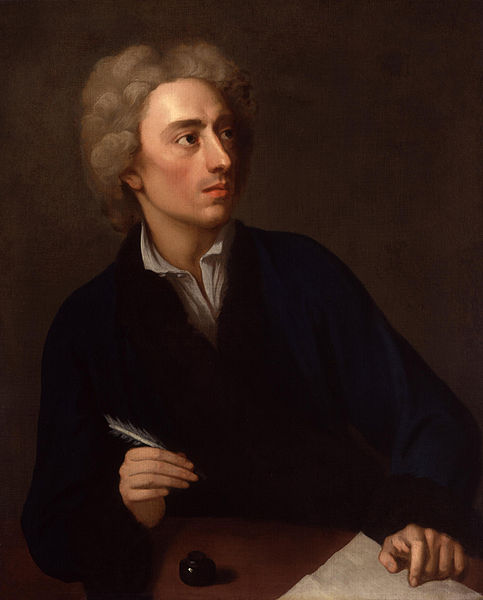

- Poet Alexander Pope, 1688

- Minister of Police Joseph Fouché, 1st Duc d'Otrante, 1759

PAGE SPONSOR

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 – 30 May 1744) was an eighteenth century English poet, best known for his satirical verse and for his translation of Homer. He is the third most frequently quoted writer in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, after Shakespeare and Tennyson. Pope is famous for his use of the heroic couplet.

Pope was born to Edith Pope (née Turner) (1643 – 1733) and Alexander Pope Senior (1646 – 1717), a linen merchant of Plough Court, Lombard Street, London, who were both Catholics. Pope's education was affected by the penal law in force at the time upholding the status of the established Church of England, which banned Catholics from teaching, attending a university, voting, or holding public office on pain of perpetual imprisonment. Pope was taught to read by his aunt, then went to Twyford School in about 1698–9. He then went to two Catholic schools in London. Such schools, while illegal, were tolerated in some areas.

In 1700, his family moved to a small estate at Popeswood in Binfield, Berkshire, close to the royal Windsor Forest. This was due to strong anti-Catholic sentiment and a statute preventing Catholics from living within 10 miles (16 km) of either London or Westminster. Pope would later describe the countryside around the house in his poem Windsor Forest. Pope's formal education ended at this time, and from then on he mostly educated himself by reading the works of classical writers such as the satirists Horace and Juvenal, the epic poets Homer and Virgil, as well as English authors such as Geoffrey Chaucer, William Shakespeare and John Dryden. He also studied many languages and read works by English, French, Italian, Latin, and Greek poets. After five years of study, Pope came into contact with figures from the London literary society such as William Wycherley, William Congreve, Samuel Garth, William Trumbull, and William Walsh.

At Binfield, he also began to make many important friends. One of them, John Caryll (the future dedicatee of The Rape of the Lock), was twenty years older than the poet and had made many acquaintances in the London literary world. He introduced the young Pope to the aging playwright William Wycherley and to William Walsh, a minor poet, who helped Pope revise his first major work, The Pastorals. He also met the Blount sisters, Teresa and (his alleged future lover) Martha, both of whom would remain lifelong friends.

From the age of 12, he suffered numerous health problems, such as Pott's disease (a form of tuberculosis that

affects the bone) which deformed his body and stunted his growth,

leaving him with a severe hunchback. His tuberculosis infection caused

other health problems including respiratory difficulties, high fevers,

inflamed eyes, and abdominal pain. He

never grew beyond 1.37 m (4 ft 6 in) tall. Pope was

already removed from society because he was Catholic; his poor health

only alienated him further. Although he never married, he had many

female friends to whom he wrote witty letters. He did have one alleged

lover, his lifelong friend, Martha Blount. In May, 1709, Pope's Pastorals was published in the sixth part of Tonson's Poetical Miscellanies. This brought instant fame to Pope. This was followed by An Essay on Criticism published in May 1711 , which was equally well received. Around 1711, Pope made friends with Tory writers John Gay, Jonathan Swift, Thomas Parnell and John Arbuthnot, who together formed the satirical Scriblerus Club.

The aim of the club was to satirise ignorance and pedantry in the form

of the fictional scholar Martinus Scriblerus. He also made friends with

Whig writers Joseph Addison and Richard Steele. In March of 1713, Windsor Forest was published and was a well known success. Pope's next well known poem was The Rape of the Lock;

first published in 1712, with a revised version published in 1714. This

is sometimes considered Pope's most popular poem because it was a

mock-heroic epic, written to make fun of a high society quarrel between Arabella Fermor (the "Belinda" of the poem) and Lord Petre,

who had snipped a lock of hair from her head without her permission. In

his poem he treats his characters in an epic style; when the Baron

steals her hair and she tries to get it back, it flies into the air and

turns into a star. During Pope's friendship with Joseph Addison, he contributed to Addison's play Cato as well as writing for The Guardian andThe Spectator. Around this time he began the work of translating the Iliad, which was a painstaking process – publication began in 1715 and did not end until 1720. In 1714, the political situation worsened with the death of Queen Anne and the disputed succession between the Hanoverians and the Jacobites, leading to the attempted Jacobite Rebellion of

1715. Though Pope as a Catholic might be expected to have supported the

Jacobites because of his religious and political affiliations,

according to Maynard Mack, "where Pope himself stood on these matters

can probably never be confidently known". These events led to an

immediate downturn in the fortunes of the Tories, and Pope's friend, Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke fled to France. An Essay on Criticism was

first published anonymously on May 15, 1711. Pope began writing the

poem early in his career and took about three years to finish it. At the time the poem was published, the heroic couplet style

(in which it was written) was a moderately new genre of poetry, and

Pope's most ambitious work. "An Essay on Criticism" was an attempt to

identify and refine his own positions as a poet and critic. The poem

was said to be a response to an ongoing debate on the question of

whether poetry should be natural, or written according to predetermined

artificial rules inherited from the classical past. The

poem begins with a discussion of the standard rules that govern poetry

by which a critic passes judgment. Pope comments on the classical

authors who dealt with such standards, and the authority that he

believed should be accredited to them. He concludes that the rules of

the ancients are identical with the rules of Nature, and fall in the

category of poetry and painting, which like religion and morality,

reflect natural law. The

poem is purposefully unclear and full of contradictions. Pope admits

that rules are necessary for the production and criticism, but gives

importance to the mysterious and irrational qualities of poetry. He

discusses the laws to which a critic should adhere while critiquing

poetry, and points out that critics serve an important function in

aiding poets with their works, as opposed to the practice of attacking

them. The

final section of "An Essay on Criticism" discusses the moral qualities

and virtues inherent in the ideal critic, who, Pope claims, is also the

ideal man. Pope had been fascinated by Homer since childhood. In 1713, he announced his plans to publish a translation of the Iliad.

The work would be available by subscription, with one volume appearing

every year over the course of six years. Pope secured a revolutionary

deal with the publisher Bernard Lintot, which brought him two hundred

guineas a volume, a very vast sum at the time. His translation of the Iliad appeared

between 1715 and 1720. It was acclaimed by Samuel Johnson as "a

performance which no age or nation could hope to equal" (although the

classical scholar Richard Bentley wrote: "It is a pretty poem, Mr.

Pope, but you must not call it Homer.").

The

money made from the Homer translation allowed Pope to move to a villa

at Twickenham in 1719, where he created his now famous grotto and

gardens. Pope decorated the grotto with alabaster, marbles, and ores

such as mundic and

crystals. He also used Cornish diamonds, stalactites, spars,

snakestones and spongestone. Here and there in the grotto he placed

mirrors that were very expensive embellishments for those times. A camera obscura was

installed to delight his visitors, of whom there were many. The

serendipitous discovery of a spring during its excavations enabled the

subterranean retreat to be filled with the relaxing sound of trickling

water, which would quietly echo around the chambers. Pope was said to

have remarked that: "Were it to have nymphs as well – it would be

complete in everything." Although the house and gardens have long since

been demolished, much of this grotto still survives. The grotto now

lies beneath St James Independent School for boys, and is opened to the

public once a year. Encouraged

by the success of the Iliad, Pope translated the Odyssey. The

translation appeared in 1726, but this time, confronted with the

arduousness of the task, he enlisted the help of William Broome and

Elijah Fenton. Pope attempted to conceal the extent of the

collaboration (he himself translated only twelve books, Broome eight

and Fenton four), but the secret leaked out. It did some damage to

Pope's reputation for a time, but not to his profits. In

this period, Pope was also employed by the publisher Jacob Tonson to

produce an opulent new edition of Shakespeare. When it finally

appeared, in 1725, this edition silently "regularised" Shakespeare's

metre and rewrote his verse in a number of places. Pope also demoted

about 1560 lines of Shakespearean material to footnotes, arguing that

they were so "excessively bad" that Shakespeare could never have

written them. (Other lines were excluded from the edition

altogether.) In 1726, the lawyer, poet, and pantomime deviser Lewis Theobald published

a scathing pamphlet called Shakespeare Restored, which catalogued the

errors in Pope's work and suggested a number of revisions to the text.

Pope and Theobald were probably well acquainted, and Pope no doubt

interpreted this as a violation of the rules of friendship. A

second edition of Pope's Shakespeare appeared in 1728, but aside from

making some minor revisions to the Preface, it seems that Pope had

little to do with it. Most later eighteenth century editors of

Shakespeare dismissed Pope's creatively motivated approach to textual

criticism. Pope's Preface, however, continued to be highly rated. It

was suggested that Shakespeare's texts were thoroughly contaminated by

actors' interpolations and they would influence editors for most of the

eighteenth century. Though the Dunciad was first published anonymously in Dublin,

its authorship was not in doubt. As well as Theobald, it pilloried a

host of other "hacks", "scribblers" and "dunces". Mack called its

publication "in many ways the greatest act of folly in Pope's life".

Though a masterpiece, "it bore bitter fruit. It brought the poet in his

own time the hostility of its victims and their sympathizers, who

pursued him implacably from then on with a few damaging truths and a

host of slanders and lies...". The threats were physical too. According

to his sister, Pope would never go for a walk without the company of his Great Dane, Bounce, and a pair of loaded pistols in his pocket. In 1731, Pope published his "Epistle to Burlington", on the subject of architecture, the first of four poems which would later be grouped under the title Moral Essays (1731 – 35). In the epistle, Pope ridiculed the bad taste of the aristocrat "Timon". Pope's enemies claimed he was attacking the Duke of Chandos and his estate, Cannons. Though the charge was untrue, it did Pope a great deal of damage. Around this time, Pope began to grow discontented with the ministry of Robert Walpole and

drew closer to the opposition led by Bolingbroke, who had returned to

England in 1725. Inspired by Bolingbroke's philosophical ideas, Pope

wrote An Essay on Man (1733

– 4). He published the first part anonymously, in a cunning and

successful

ploy to win praise from his fiercest critics and enemies. Despite

the 'Essay' being written in heroic couplets, many translations into

European languages rapidly followed, especially in Germany, where the

'Essay' was regarded as a serious contribution to philosophy. The Imitations of Horace followed

(1733 – 38). These were written in the popular Augustan form of the

"imitation" of a classical poet, not so much a translation of his works

as an updating with contemporary references. Pope used the model of Horace to satirise life under George II,

especially what he regarded as the widespread corruption tainting the

country under Walpole's influence and the poor quality of the court's

artistic taste. Pope also added a wholly original poem, An Epistle to Doctor Arbuthnot, as an introduction to the "Imitations". It reviews his own literary career and includes the famous portraits of Lord Hervey ("Sporus") and Addison ("Atticus"). In 1738 he wrote the Universal Prayer. After 1738, Pope wrote little. He toyed with the idea of composing a patriotic epic in blank verse called Brutus, but only the opening lines survive. His major work in these years was revising and expanding his masterpiece The Dunciad.

Book Four appeared in 1742, and a complete revision of the whole poem

in the following year. In this version, Pope replaced the "hero", Lewis

Theobald, with the poet laureate Colley Cibber as

"king of dunces". By now Pope's health, which had never been good, was

failing, and he died in his villa surrounded by friends on 30 May 1744.

On the previous day, 29 May 1744, Pope called for a priest and received

the Last Rites of the Catholic Church. He lies buried in the nave of the Church of St Mary the Virgin in Twickenham.