<Back to Index>

- Explorer Francisco Pascacio Moreno, 1852

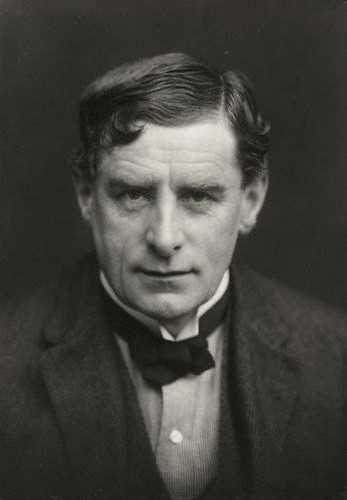

- Painter Walter Richard Sickert, 1860

- King of Portugal and the Algarves Manuel I, 1469

PAGE SPONSOR

Walter Richard Sickert (31 May 1860 – 22 January 1942) was a German-born English Impressionist painter and a member of the Camden Town Group. Sickert was a cosmopolitan and eccentric who favoured ordinary people and urban scenes as his subjects.

Sickert was born in Munich, in Bavaria. His father, Oswald Sickert, was a Danish-German artist and his mother Eleanor Louisa Henry was the illegitimate daughter of the English astronomer Richard Sheepshanks. The family left Munich to settle in England at the time of the Great Exhibition, Oswald's work having been recommended by Freiherrin Rebecca von Kreusser to Ralph Nicholson Wornum, who was Keeper of the National Gallery at the time. The young Sickert was sent to University College School from 1870 - 1871 before transferring to King's College School, Wimbledon, where he studied until the age of 18. Though he was the son and grandson of painters, he at first sought a career as an actor; he appeared in small parts in Sir Henry Irving's company, before taking up the study of art as assistant to James Abbott McNeill Whistler. He later went to Paris and met Edgar Degas, whose use of pictorial space and emphasis on drawing would have a powerful effect on Sickert's own work.

He developed a personal version of Impressionism, favouring sombre colouration. Following Degas' advice, Sickert painted in the studio, working from drawings and memory as an escape from "the tyranny of nature". Sickert's earliest major works were portrayals of scenes in London music halls, often depicted from complex and ambiguous points of view, so that the spatial relationship between the audience, performer and orchestra becomes confused, as figures gesture into space and others are reflected in mirrors. The isolated rhetorical gestures of singers and actors seem to reach out to no-one in particular, and audience members are portrayed stretching and peering to see things that lie beyond the visible space. This theme of confused or failed communication between people appears frequently in his art.

By emphasising the patterns of wallpaper and architectural decorations, Sickert created abstract decorative arabesques and flattened the three-dimensional space. His music hall pictures, like Degas' paintings of dancers and café-concert entertainers, connect the artificiality of art itself to the conventions of theatrical performance and painted backdrops. Many of these works were exhibited at the New English Art Club, a group of French-influenced realist artists with which Sickert was associated. At this period Sickert spent much of his time in France, especially in Dieppe where his mistress, and possibly his illegitimate son, lived.

Just before World War I he championed the avant-garde artists Lucien Pissarro, Jacob Epstein, Augustus John and Wyndham Lewis. At the same time he founded, with other artists, the Camden Town Group of British painters, named from the district of London in

which he lived. This group had been meeting informally since 1905, but

was officially established in 1911. It was influenced by Post-Impressionism and Expressionism, but concentrated on scenes of often drab suburban life; Sickert himself said he preferred the kitchen to the drawing room as a scene for paintings. Sickert regularly portrayed figures placed ambiguously on the borderland between respectability and poverty. From 1908 - 1912 and again from 1915 - 1918 Sickert was an influential teacher at Westminster School of Art. On 11 September 1907, Emily Dimmock,

a prostitute cheating on her partner, was murdered in her home at Agar

Grove (then St Paul's Road), Camden. After sex, the man had slit her

throat open while she was asleep, then left in the morning. The "Camden Town murder" became an ongoing source of prurient sensationalism in the press. For

several years Sickert had already been painting lugubrious female nudes

on beds, and continued to do so, deliberately challenging the

conventional approach to life painting — "The modern flood of

representations of vacuous images dignified by the name of 'the nude'

represents an artistic and intellectual bankruptcy" — giving four of

them, which included a male figure, the title, The Camden Town Murder, and causing a controversy, which ensured attention for his work. These

paintings do not show violence, however, but a sad thoughtfulness,

explained by the fact that three of them were originally exhibited with

completely different titles, one more appropriately being What Shall We Do for the Rent?, and the first in the series, Summer Afternoon. These and other works were painted in heavy impasto and

narrow tonal range. Many other obese nudes were painted at this time,

in which the fleshiness of the figures is connected to the thickness of

the paint, devices that were later adapted by Lucian Freud. Sickert's interest in Victorian narrative genres also influenced his best known work, Ennui,

in which a couple in a dingy interior gaze abstractedly into empty

space, as though they can no longer communicate with each other. In his

later work Sickert adapted illustrations by Victorian artists such as

Georgie Bowers and John Gilbert,

taking the scenes out of context and painting them in poster-like

colours so that the narrative and spatial intelligibility partly

dissolved. He called these paintings his "Echoes". Sickert

also executed a number of works in the 1930s based on news photographs,

squared up for enlargement, with their pencil grids plainly visible in

the finished paintings. Seen by many of his contemporaries as evidence

of the artist's decline, these works are also the artist's most

forward-looking, seeming to prefigure the practices of Chuck Close and Gerhard Richter. He is considered an eccentric figure of the transition from Impressionism to modernism, and as an important influence on distinctively British styles of avant-garde art in the 20th century. One of Sickert's closest friends and supporters was newspaper baron Lord Beaverbrook,

who accumulated the largest single collection of Sickert paintings in

the world. This collection, with a private correspondence between

Sickert and Beaverbook, is in the Beaverbrook Art Gallery in Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada. Sickert's sister was Helena Swanwick, a feminist and pacifist active in the women's suffrage movement.

Sickert died in Bath, England in 1942 at the age of 81. He had been married three times. His first wife, Ellen Cobden, was a daughter of Richard Cobden. His third wife was the painter Thérèse Lessore. Sickert took a keen interest in the Jack the Ripper crime and believed he had lodged in the room used by the infamous serial killer,

having been told this by his landlady, who suspected a previous lodger.

He painted the room, entitling it "Jack the Ripper's bedroom" and

portraying it as a dark, brooding and almost unintelligible space. The

painting is displayed in the Manchester City Art Gallery. In 1976, Stephen Knight's Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution claimed that Sickert had been forced to become an accomplice in the Ripper murders. Knight's information came from Joseph Gorman,

who claimed to be Sickert's illegitimate child. Even though Gorman

later admitted he had made up the tale, Knight's book is responsible

for a popular conspiracy theory, which accuses royalty and freemasonry of complicity in the murders. Jean Overton Fuller, in Sickert and the Ripper Crimes (1990), went so far as to claim that Sickert was the actual killer. In 2002, crime novelist Patricia Cornwell, in Portrait of a Killer: Jack the Ripper - Case Closed,

presented her theory that Sickert was responsible for the murders, one

of the motivating factors being an alleged defect in his penis. Cornwell purchased 31 of Sickert's paintings and it is claimed that she destroyed one or more of them (a claim she denies) searching for his DNA. Cornwell

claimed she was able to scientifically prove the DNA on a letter

attributed to the Ripper and one written by Sickert belong to only one

per cent of the population. Cornwell's theory was not met with support in the art world. The

Oxford National Dictionary of Biography, in its article on Sickert,

dismisses as "fantasy" any theory that he was the Ripper.