<Back to Index>

- Polymath Jan Brożek, 1585

- Painter Konrad Vilhelm Mägi, 1878

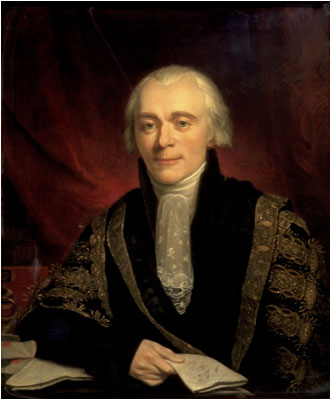

- Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Spencer Parceval, 1762

PAGE SPONSOR

Spencer Perceval, KC (1 November 1762 – 11 May 1812) was a British statesman and Prime Minister. He is the only British Prime Minister to have been assassinated. He is the only Solicitor General or Attorney General, and one of very few lawyers, to have been Prime Minister. The younger son of an Irish earl, Perceval was educated at Harrow and Trinity College, Cambridge. He studied law at Lincoln’s Inn, practised as a barrister on the Midland Circuit and became a King’s Counsel, before entering politics at the age of 33 as a Member of Parliament for Northampton. A follower of William Pitt, Perceval always described himself as a ‘friend of Mr Pitt’ rather than a Tory. Perceval was opposed to Catholic emancipation and reform of Parliament; he supported the war against Napoleon and the abolition of the slave trade. He was opposed to hunting, gambling and adultery, did not drink as much as most Members of Parliament, gave generously to charity, and enjoyed spending time with his twelve children.

After a

late entry into politics his rise to power was rapid; he was Solicitor

and then Attorney General in the Addington Ministry, Chancellor of

the Exchequer and Leader of the

House of Commons in

the Portland Ministry,

and became Prime Minister in October 1809. At the head of a weak

ministry, Perceval faced a number of crises during his term in office

including an inquiry into the disastrous Walcheren

expedition, the madness of King George III,

economic depression and Luddite riots. He survived these

crises, successfully pursued the Peninsular War in the face of opposition

defeatism, and won the support of the Prince Regent.

His position was looking stronger by the spring of 1812, when a man

with a grievance against the Government shot him dead in the lobby of

the House of Commons.

Although Perceval was a seventh son and had four older brothers who

survived to adulthood, the Earldom of

Egmont reverted to

one of his great-grandsons in the early twentieth century and remains

in the hands of his descendants. Perceval

was the seventh son of John Perceval,

2nd Earl of Egmont, the second son of the earl’s second

marriage. His mother, Catherine Compton, Baroness Arden, was a

grand-daughter of the 4th Earl of

Northampton. Spencer was a Compton family name; Catherine

Compton's great uncle Spencer

Compton, 1st Earl of Wilmington, had been Prime Minister. His

father, a political advisor to Frederick,

Prince of Wales and King George III,

served briefly in the Cabinet as First Lord of

the Admiralty and

Perceval’s early childhood was spent at Charlton House, which his father had

taken to be near Woolwich docks.

Perceval’s father died when he was eight. Perceval went to Harrow,

where he was a disciplined and hard working pupil. It was at Harrow

that he developed an interest in evangelical Anglicanism and formed what was to be a

life long friendship with Dudley Ryder.

After five years at Harrow he followed his older brother Charles to Trinity College, Cambridge,

where he won the declamation prize in English and graduated in 1782. As

the second son of a second marriage, and with an allowance of only

£200 a year, Perceval faced the prospect of having to make his

own way in life. He chose the law as a profession, studied at Lincoln’s Inn,

and was called to the bar in 1786. Perceval’s mother had died in 1783,

and Perceval and his brother Charles, now Lord Arden, rented a house in

Charlton, where they fell in love with two sisters who were living in

the Percevals' old childhood home. The sisters’ father, Sir Thomas

Spencer Wilson, approved of the match between his eldest daughter

Margaretta and Lord Arden, who was wealthy and already a Member of

Parliament and a Lord of the Admiralty. Perceval, who was at that time

an impecunious barrister on the Midland Circuit, was told to wait until

younger daughter Jane came of age in three years’ time. When Jane

reached 21 in 1790 Perceval’s career was still not prospering, and Sir

Thomas still opposed the marriage. So the couple eloped and married by

special licence in East Grinstead.

They set up home together in lodgings over a carpet shop in Bedford Row, later moving to Lindsey House, Lincoln's Inn

Fields. Perceval’s

family connections obtained a number of positions for him: Deputy

Recorder of Northampton, and Commissioner of Bankrupts in 1790;

Surveyor of the Maltings and Clerk of the Irons in the Mint - a

sinecure worth £119 a year – in 1791; counsel to the Board of

Admiralty in 1794. He acted as junior counsel for the Crown in the

prosecutions of Thomas Paine in absentia for seditious libel (1792), and John Horne Tooke for

high treason (1794). Perceval joined the Light Horse Volunteers in 1794

when the country was under threat of invasion by France. Perceval

wrote anonymous pamphlets in favour of the impeachment of Warren Hastings,

and in defence of public order against sedition. These pamphlets

brought him to the attention of William Pitt and in 1795 he was offered

the appointment of Chief Secretary

for Ireland. He declined the offer. He

could earn more as a barrister and needed the money to support his

growing family. In 1796 he became a King’s Counsel and had an income of

about £1000 a year. In

1796 Perceval’s uncle, the 8th Earl of Northampton, died. Perceval’s

cousin, who was MP for Northampton, succeeded to the Earldom and took

his place in the House of Lords.

Perceval was invited to stand for election in his place. In the May

by-election he was elected unopposed, but weeks later had to defend his

seat in a fiercely contested general election. Northampton had an

electorate of about one thousand - every male householder not in

receipt of poor relief had a vote - and the town had a strong radical

tradition. Perceval stood for the Castle Ashby interest, Edward Bouverie for the Whigs,

and William Walcot for the corporation. After a disputed count Perceval

and Bouverie were returned. Perceval represented Northampton until his

death 16 years later, and is the only MP for Northampton to have held

the office of Prime Minister. 1796 was his first and last contested

election; in the general elections of 1802, 1806 and 1807 Perceval and

Bouverie were returned unopposed. When

Perceval took his seat in the House of Commons in September 1796 his

political views were already formed. "He was for the constitution and

Pitt; he was against Fox and France", wrote his biographer Denis Gray. During

the 1796 - 1797 session he made several speeches, always reading from

notes. His public speaking skills had been sharpened at the Crown and

Rolls debating society when he was a law student. After taking his seat

in the House of Commons, Perceval continued with his legal practice as

MPs did not receive a salary, and the House only sat for a part of the

year. During the Parliamentary recess of the summer of 1797 he was

senior counsel for the Crown in the prosecution of John Binns for

sedition. Binns, who defended by Samuel Romilly,

was found not guilty. The fees from his legal practice allowed Perceval

to take out a lease on a country house, Belsize House in Hampstead. It

was during the next session of Parliament, in January 1798, that

Perceval established his reputation as a debater - and his prospects as

a future minister - with a speech in support of the Assessed Taxes Bill

(a bill to increase the taxes on houses, windows, male servants, horses

and carriages, in order to finance the war against France). He used the

occasion to mount an attack on Charles Fox and

his demands for reform. Pitt described the speech as one of the best he

had ever heard, and later that year Perceval was given the post of

Solicitor to the Ordnance. Pitt

resigned in 1801 when the King and Cabinet opposed his bill for

Catholic emancipation. As Perceval shared the King’s views on Catholic

emancipation he did not feel obliged to follow Pitt into opposition and

his career continued to prosper during Henry Addington’s

administration. He was appointed Solicitor General in 1801 and Attorney

General the following year. Perceval did not agree with Addington's

general policies (especially on foreign policy), and confined himself

to speeches on legal issues. He kept the position of Attorney General

when Addington resigned and Pitt formed his second ministry in 1804. As

Attorney General Perceval was involved with the prosecution of radicals Edward Despard and William Cobbett,

but was also responsible for more liberal decisions on trade unions,

and for improving the conditions of convicts transported to New South Wales. Pitt

died in January 1806. Perceval was an emblem bearer at his funeral and,

although he had little money to spare (by now he had eleven children),

he contributed £1000 towards a fund to pay off Pitt’s debts. He

resigned as Attorney General, refusing to serve in Lord Grenville’s

ministry of "All the Talents" as it included Fox. Instead he became the

leader of the Pittite opposition in the House of Commons. During

his period in opposition, Perceval’s legal skills were put to use to

defend Princess

Caroline,

the estranged wife of the Prince of Wales, during the "delicate

investigation". The Princess had been accused of giving birth to an

illegitimate child and the Prince of Wales ordered an inquiry, hoping

to obtain evidence for a divorce. The Government inquiry found that the

main accusation was untrue (the child in question had been adopted by

the princess) but was critical of the behaviour of the princess. The

opposition sprang to her defence and Perceval became her advisor,

drafting a 156 page letter in her support to King George III. Known as

"The Book", it was described by Perceval’s biographer as "the last and

greatest production of his legal career". When

the King refused to let Caroline return to court, Perceval threatened

publication of the book. But Grenville’s ministry fell - again over a

difference of opinion with the King on the Catholic question - before

the book could be distributed and, as a member of the new Government,

Perceval drafted a cabinet minute acquitting Caroline on all charges

and recommending her return to court. He had a bonfire of the book at

Lindsey House and large sums of Government money were spent on buying

back stray copies, but a few remained at large and "The Book" was

published soon after his death. On

the resignation of Grenville, the Duke of Portland put together a

ministry of Pittites and asked Perceval to become Chancellor of the

Exchequer and Leader of the House of Commons. Perceval would have

preferred to remain Attorney General or become Home Secretary,

and pleaded ignorance of financial affairs. He agreed to take the

position when the salary (smaller than that of the Home Office) was

augmented by the Duchy of

Lancaster. Lord Hawkesbury (later

Liverpool) recommended him to the King by explaining that he came from

an old English family and shared the King’s views on the Catholic

question. Perceval’s

youngest child, Ernest Augustus,was born soon after Perceval became

Chancellor (Princess Caroline was godmother). Jane Perceval became ill

after the birth and the family moved out of the damp and draughty

Belsize House, spending a few months in Lord Teignmouth’s

house in Clapham before finding a suitable

country house in Ealing.

Elm Grove was a sixteenth century house that had been the home of the

Bishop of Durham; Perceval

paid £7,500 for it in 1808 (borrowing from his brother Lord Arden

and the trustees of Jane’s dowry) and the Perceval family’s long

association with Ealing began. Meanwhile, in town, Perceval had moved

from Lindsey House into 10 Downing

Street, when the Duke of Portland moved back to Burlington House shortly after becoming

Prime Minister. One

of Perceval’s first tasks in Cabinet was to expand the Orders in

Council that had been brought in by the previous administration and

were designed to restrict the trade of neutral countries with France,

in retaliation to Napoleon’s embargo on British trade. He was also

responsible for ensuring that Wilberforce’s

Bill on the Abolition of the Slave Trade, which had still not passed it

final stages in the House of Lords when Grenville’s ministry fell,

would not "fall between the two ministries" and be rejected in a snap

division. Perceval

was one of the founding members of the African Institute, which was set

up in April 1807 to safeguard the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act. As

Chancellor of the Exchequer Perceval had to raise money to finance the

war against Napoleon. This he managed to do in his budgets of 1808 and

1809 without increasing taxes, by raising loans at reasonable rates and

making economies. As leader of the House of Commons he had to deal with

a strong opposition, which challenged the government over the conduct

of the war, Catholic emancipation, corruption and Parliamentary reform.

Perceval successfully defended the Commander-in-Chief of the army, the Duke of York,

against charges of corruption when the Duke’s ex-mistress Mary Anne

Clarke claimed to have sold army commissions with his knowledge.

Although Parliament voted to acquit the Duke of the main charge, his

conduct was criticised and he accepted Perceval’s advice to resign. (He

was to be re-instated in 1811). Portland’s

ministry contained three future prime ministers - Perceval, Lord

Hawkesbury and George Canning - as well as another two of

the nineteenth century’s great statesmen - Lord Eldon and Lord Castlereagh.

But Portland was not a strong leader and his health was failing. The

country was plunged into political crisis in the summer of 1809 as

Canning schemed against Castlereagh and the Duke of Portland resigned

following a stroke. Negotiations began to find a new Prime Minister:

Canning wanted to be Prime Minister or nothing, Perceval was prepared

to serve under a third person, but not Canning. The remnants of the

cabinet decided to invite Lord Grey and Lord Grenville to form "an

extended and combined administration"

in

which Perceval was hoping for the Home Secretaryship. But Grenville and

Grey refused to enter into negotiations, and the King accepted the

Cabinet’s recommendation of Perceval for his new Prime Minister.

Perceval kissed the king’s hands on 4th October and set about forming

his Cabinet, a task made more difficult by the fact that Castlereagh

and Canning had ruled themselves out of consideration by fighting a

duel (which Perceval had tried to prevent). Having received five

refusals for the office, he had to serve as his own Chancellor of the

Exchequer - characteristically declining to accept the salary. The

new ministry was not expected to last. It was especially weak in the

Commons, where Perceval had only one cabinet member - Home Secretary Richard Ryder -

and had to rely on the support of backbenchers in debate. In the first

week of the new Parliamentary session in January 1810 the Government

lost four divisions, one on a motion for an inquiry into the disastrous

Walcheren expedition (in which, the previous summer, a military force

intending to seize Antwerp had instead withdrawn after

losing many men to an epidemic on the island of Walcheren)

and three on the composition of the finance committee. The Government

survived the inquiry into the Walcheren expedition at the cost of the

resignation of the expedition’s leader Lord Chatham.

The radical MP Sir Francis

Burdett was

committed to the Tower of London for having published a

letter in William Cobbett’s Political

Register denouncing

the government’s exclusion of the press from the inquiry. It took three

days, owing to various blunders, to execute the warrant for Burdett’s

arrest. The mob took to the streets in support of Burdett, troops were

called out, and there were fatal casualties. As chancellor, Perceval

continued to find the funds to finance Wellington’s campaign in the Iberian

Peninsula, whilst contracting a lower debt than his predecessors or

successors. King

George III had celebrated his 50th jubilee in 1809; by the following

autumn he was showing signs of a return of the derangement that had led

to a Regency in 1788. The prospect of another Regency was not

attractive to Perceval, as the prince of Wales was known to favour

Whigs and disliked Perceval for the part he had played in the "delicate

investigation". Twice parliament was adjourned in November 1810, as

doctors gave optimistic reports about the King’s chances of a return to

health. In December select committees of the Lords and Commons heard

evidence from the doctors, and Perceval finally wrote to the Prince of

Wales on 19 December saying that he planned the next day to introduce a

Regency Bill. As with Pitt’s bill in 1788, there would be restrictions;

the Regent’s powers to create peers and award offices and pensions

would be restricted for 12 months, the Queen would be responsible for

the care of the King, and the King’s private property would be looked

after by trustees. The

Prince of Wales, supported by the opposition, objected to the

restrictions, but Perceval steered the bill through Parliament.

Everyone had expected the Regent to change his ministers but,

surprisingly, he chose to retain his old enemy Perceval. The official

reason given by the Regent was that he did not wish to do anything to

aggravate his father’s illness. The King signed the Regency Bill on 5

February, the Regent took the royal oath the following day and

Parliament formally opened for the 1811 session. The session was

largely taken up with problems in Ireland, economic depression and the

bullion controversy in England (a Bill was passed to make bank notes

legal tender), and military operations in the Peninsula.

The

restrictions on the Regency expired in February 1812, the King was

still showing no signs of recovery, and the Prince Regent decided,

after an unsuccessful attempt to persuade Grey and Grenville to join

the government, to retain Perceval and his ministers. Wellesley,

after intrigues with the Prince Regent, resigned as Foreign Secretary

and was replaced by Castlereagh. The opposition meanwhile was mounting

an attack on the Orders in Council, which had caused a crisis in

relations with America and were widely blamed for depression and

unemployment in England. Rioting had broken out in the Midlands and

North, and been harshly repressed. Henry Brougham’s

motion

for a select committee was defeated in the commons, but, under

continuing pressure from manufacturers, the government agreed to

set up a committee of the whole house to consider the Orders in Council

and their impact on trade and manufacture. The committee began its

examination of witnesses in early May 1812. At

5:15 on the evening of 11 May 1812, Perceval was on his way to attend

the inquiry into the Orders in Council. As he entered the lobby of the

House of Commons, a man stepped forward, drew a pistol and shot him in

the chest. Perceval fell to the floor, after uttering something that

was variously heard as "murder" or "oh my God". They

were his last words. By the time he had been carried into an adjoining

room and propped up on a table with his feet on two chairs, he was

senseless, although there was still a faint pulse. When a surgeon

arrived a few minutes later, the pulse had stopped, and Perceval was

declared dead. At

first it was feared that the shot might signal the start of an

uprising, but it soon became apparent that the assassin – who had made

no attempt to escape – was a man with an obsessive grievance against

the Government and had acted alone. John Bellingham was

a merchant who had been unjustly imprisoned in Russia and felt he was

entitled to compensation from the Government, but all his petitions had

been rejected. Perceval’s

body was laid on a sofa in the speaker’s drawing room and removed to

Number 10 Downing Street in the early hours of 12 May. That same

morning an inquest was held at the Cat and Bagpipes public house on the

corner of Downing Street and verdict of wilful murder was returned. Perceval

left a widow and twelve children aged between twenty and three, and

there were soon rumours that he had not left them well provided for. He

had just £106 5s 1d in the bank when he died. A

few days after his death, Parliament voted to settle £50,000 on

Perceval’s children, with additional annuities for his widow and eldest

son. Jane Perceval married

Lieutenant Colonel Sir Henry Carr in 1815 and was widowed again six

years later. She died aged 74 in 1844. Perceval

was buried on 16 May in the Egmont vault at Charlton. At his widow's

request, it was a private funeral. Lords Eldon, Liverpool, and

Harrowby, and Richard Ryder, were pall-bearers. The previous day,

Bellingham had been tried, and, refusing to enter a plea of insanity,

was found guilty. He was hanged on 18 May. Perceval

was a small, slight, and very pale man, who usually dressed in black.

Lord Eldon called him "Little P". He

never sat for a full sized portrait; likenesses are either miniatures

or are based on a death mask by Joseph Nollekens.

He is sometimes referred to as one of Britain's forgotten prime

ministers, remembered only for the manner of his death. Although

not considered an inspirational leader, he is generally seen as a

devout, industrious, principled man who at the head of a weak

government steered the country through difficult times. A contemporary

MP Henry Grattan,

used a naval analogy to describe Perceval: "He is not a

ship-of-the-line, but he carries many guns, is tight-built and is out

in all weathers". Perceval's

modern biographer, Denis Gray, described him as "a herald of the

Victorians". The perception that Perceval

was uninspiring did not dim his personal appeal, however, as Landsman

notes: "Percival [sic]

was an exceedingly popular leader. The judge in the case literally wept

as he made his closing remarks to the jury." Public

monuments to Perceval were erected in Northampton, Lincoln's Inn and

Westminster Abbey. Four biographies about Perceval have been published:

a book on his life and administration by Charles Verulam Williams

appeared soon after his death; his grandson Spencer Walpole's biography

in 1894; Philip Treherne's short biography in 1909; Denis Gray's

500-page political biography in 1963. In addition there are two books

about his assassination, one by Mollie Gillen and one by David

Hanrahan. Perceval's assassination inspired poems such as Universal sympathy on

the martyr'd statesman (1812): In 2007

the band iLiKETRAiNS produced a single about

Perceval's assassination.