<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Raphael Mitchel Robinson, 1911

- Poet Odysseas Elytis, 1911

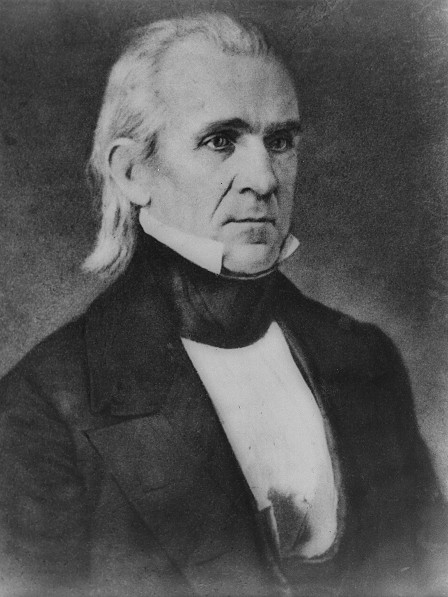

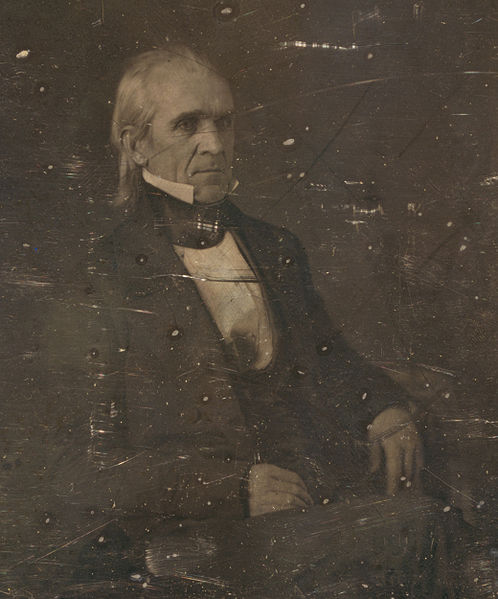

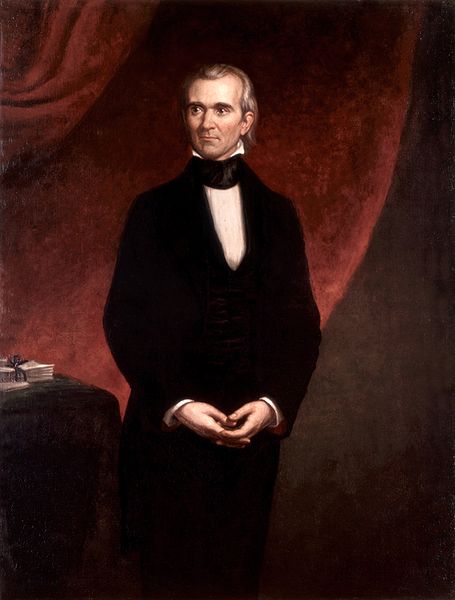

- 11th President of the United States James Knox Polk, 1795

PAGE SPONSOR

James Knox Polk (November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th President of the United States (1845 – 1849). Polk was born in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. He later lived in and represented the state of Tennessee. A Democrat, Polk served as Speaker of the House (1835 – 1839) and Governor of Tennessee (1839 – 1841). Polk was the surprise ("dark horse") candidate for president in 1844, defeating Henry Clay of the rival Whig Party by promising to annex Texas. Polk was a leader of Jacksonian Democracy during the Second Party System.

Polk was

the last strong pre-Civil War president. Polk is noted

for his foreign policy successes. He threatened war with Britain then backed away and split the

ownership of the Oregon region (the Pacific

Northwest) with Britain. When Mexico rejected American

annexation of Texas, Polk led the nation to a sweeping victory in the Mexican –

American War, followed by purchase of California, Arizona, and

New Mexico. He secured passage of the Walker tariff of 1846, which had low

rates that pleased his native South. He established a treasury system

that lasted until 1913. Polk oversaw the opening of the U.S. Naval

Academy and the Smithsonian

Institution, the groundbreaking for the Washington

Monument, and the issuance of the first postage stamps in

the United States. He promised to serve only one term and did not run

for reelection. He died of cholera three months after his term

ended. Scholars have ranked him

favorably on the list

of greatest presidents for

his ability to set an agenda and achieve all of it. Polk has been

called the "least known consequential president" of the United States. James

Knox Polk, the first of ten children, was born in a farmhouse (possibly

a "log" cabin) in what is

now Pineville,

North Carolina, in Mecklenburg

County on

November 2, 1795, just outside of Charlotte. His father, Samuel Polk, was a

slaveholder, successful farmer and surveyor of Scots - Irish descent. His mother, Jane

Polk (née Knox), was a descendant of a brother of the Scottish religious reformer John Knox.

She named her firstborn after her father James Knox. Like most early Scots - Irish

settlers in the North Carolina mountains, the Knox and Polk families

were Presbyterian.

While Jane remained a devout Presbyterian her entire life, Samuel

(whose father, Ezekial Polk, was a deist)

rejected dogmatic Presbyterianism. When the parents took James to

church to be baptized, the father Samuel refused to declare his belief

in Christianity, and the minister refused to baptize the child. In 1803, the majority of Polk's

relatives moved to the Duck River area in what is now Maury County,

Middle Tennessee; Polk's family waited until 1806 to follow. The family grew prosperous,

with Samuel Polk turning to land speculation and becoming a county

judge. Polk was home schooled. His health was problematic and in 1812

his pain became so unbearable that he was taken to Dr. Ephraim

McDowell of Danville,

Kentucky, who conducted an

operation to remove urinary

stones. The operation was conducted while Polk

was awake, with nothing but brandy then available for anesthetic, but it was successful. The surgery may

have left Polk sterile, as he did not sire any children. When

Polk recovered, his father offered to bring him into the mercantile

business, but Polk refused. In

July 1813, Polk enrolled at the Zion Church near his home. A year later

he attended an academy in Murfreesboro,

where he may have met his future wife, Sarah Childress. At Murfreesboro, Polk was

regarded as a promising student. In January 1816, he transferred and

was admitted into the University of

North Carolina as

a second semester sophomore. The Polks had connections with the

university, then a small school of about eighty students: Sam Polk was

their land agent for Tennessee, and his cousin, William Polk, was a

trustee. While there, Polk

joined the Dialectic

Society, in which he regularly took part in debates and learned

the art of oratory.

His roommate William Dunn

Moseley later

became the first governor of Florida. Polk graduated with honors in May

1818. After graduation, Polk traveled to Nashville to study law under renowned Nashville

trial attorney Felix

Grundy. Grundy became Polk's first mentor. On

September 20, 1819, Polk was elected to be the clerk for the Tennessee

State Senate with Grundy's endorsement. Polk was reelected as clerk in 1821

without opposition, and would continue to serve until 1822. Polk was

admitted to the bar in

June 1820 and his first case was to defend his father against a public

fighting charge, a case which he was able to get his father's release

for a fine of one dollar. Polk's practice was successful as there

were many cases regarding the settlement of debts following the Panic

of 1819. In

1821 Polk joined the local militia with the rank of Captain, and was

soon promoted to Colonel. Polk's

oratory became popular, earning him the nickname "Napoleon of the

Stump." In 1822 Polk resigned his position as clerk to run his

successful campaign for the Tennessee state legislature in 1823, in

which he defeated incumbent William Yancey,

becoming the new representative of Maury County. In October 1823 Polk voted for Andrew Jackson to become the next United

States Senator from Tennessee. Jackson won and from then on

Polk was a firm supporter of Jackson. Polk

courted Sarah Childress,

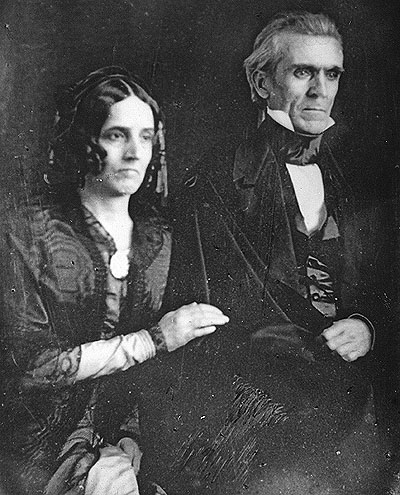

and they married on January 1, 1824. Polk

was then 28, and Sarah was 20 years old. Through their marriage they

had no children. They were married until his death in 1849. During

Polk's political career, Sarah was said to assist her husband with his

speeches, give him advice on policy matters and was always active in

his campaigns. An old story told that Andrew Jackson had encouraged

their romance when they began to court. In 1824, Jackson ran

for President but was defeated. Though Jackson had won the popular

vote, neither he nor any of

the other candidates (John

Quincy Adams, Henry

Clay, and William

H. Crawford)

had obtained a majority of the electoral vote. The House of

Representatives then had to select the verdict; Clay, who had received

the least amount of electoral votes and therefore was dropped from the

ballot, supported Adams. Clay's support proved to be the deciding

factor in the House and Adams was elected President. Adams then offered Clay a position in the

Cabinet as Secretary

of State. In

1825, Polk ran for the United States

House of Representatives for

the Tennessee's 6th

congressional district. Polk vigorously campaigned in

the district. Polk was so active that Sarah began to worry about his

health. During

the campaign, Polk's opponents said that at the age of 29 Polk was too

young for a spot in the House. However, Polk won the election and took

his seat in Congress. When Polk arrived in Washington D.C. he

roomed in a boarding house with some other Tennessee representatives,

including Benjamin Burch. Polk made his first major speech on March 13,

1826, in which he said that the Electoral

College should

be abolished and that the President should be elected by the popular

vote. After

Congress went into recess in the summer of 1826, Polk returned to

Tennessee to see Sarah, and when Congress met again in the autumn, Polk

returned to Washington with Sarah. In 1827 Polk was reelected to

Congress. In

1828, Jackson ran for President again and during the campaign Polk and

Jackson corresponded, with Polk giving Jackson advice on his campaign.

With Jackson's victory in the election Polk began to support the

administration's position in Congress. During

this time, Polk continued to be reelected in the House. In August 1833,

after being elected to his fifth term, Polk became the chair of the

House Ways and Means Committee. In

June 1834, Speaker of the House Andrew Stevenson resigned, leaving the spot

for speaker open. Polk ran against fellow

Tennessean

John Bell for

Speaker, and, after ten ballots, Bell won. However, in 1835, Polk ran

against Bell for Speaker again and won.

Polk

worked for Jackson's policies as speaker, and Van Buren's when he

succeeded Jackson in 1837; he appointed committees with Democratic

chairs and majorities, including the New York radical C.C. Cambreleng as Chair of the Ways and Means

Committee, although he maintained the facade of traditional

bipartisanship. The two major issues during

Polk's speakership were slavery and the economy, following the Panic of 1837.

Van Buren and Polk faced pressure to rescind the Specie Circular,

an act that had been passed by Jackson, in an attempt to help the

economy. The act required that payment for government lands be in gold

and silver. However, with support from Polk and his cabinet, Van Buren

chose to stick with the Specie Circular. Polk

attempted to make a more orderly house. He never challenged anyone to a

duel no matter how much they insulted his honor as was customary at the

time. Polk also issued the gag

rule on petitions from abolitionists. In

1838, the political situation in Tennessee — where, in 1835, Democrats

had lost the governorship for the first time in their party's history —

persuaded Polk to return to help the party at home. Leaving Congress in 1839, Polk

became a candidate in the Tennessee gubernatorial election, defeating

the incumbent Whig, Newton Cannon by about 2,500 votes, out

of about 105,000. Polk's

three major programs during his governorship; regulating state banks,

implementing state internal improvements, and improving education all

did not get approval by the legislature. In the presidential

election of 1840, Van Buren

was overwhelmingly defeated by a popular Whig, William

Henry Harrison. Polk received

one electoral vote from Tennessee for Vice

President in the election. Polk lost his own reelection bid to a

Whig, James

C. Jones, in 1841, by 3,243

votes. He

challenged Jones in 1843, campaigning across the state and publicly

debating against Jones, but was defeated again, this time by a slightly

greater margin of 3,833 votes. Polk

initially hoped to be nominated for vice-president at the Democratic

convention,

which began on May 27, 1844. The leading contender for the presidential

nomination was former President Martin Van Buren, who wanted to stop

the expansion of slavery. Other candidates included James Buchanan,

General

Lewis Cass, Cave Johnson, John C. Calhoun,

and Levi Woodbury.

The primary point of political contention involved the Republic of

Texas, which, after declaring independence from Mexico in

1836, had asked to join the United States. Van Buren opposed the

annexation but in doing so lost the support of many Democrats,

including former President Andrew Jackson, who still had much

influence. Van Buren won a simple majority on the convention's first

ballot but did not attain the two-thirds supermajority required for

nomination. After six more ballots, when it became clear that Van Buren

would not win the required majority, Polk was put forth as a "dark horse"

candidate. The eighth ballot was also indecisive, but on the ninth, the

convention unanimously nominated Polk, supported by Jackson. Before

the convention, Jackson told Polk that he was his favorite for the

nomination of the Democratic Party. Even with this support, Polk still

instructed his managers at the convention to support Van Buren, but

only if it was certain that Van Buren had a chance to win the

nomination. This assured that if a deadlocked convention occurred,

initial supporters of Van Buren would pick Polk as a compromise

candidate for the Democrats. In the end, this is exactly what happened

as a result for Polk's support of westward expansion. When

advised of his nomination, Polk replied: "It has been well observed

that the office of President of the United States should neither be

sought nor declined. I have never sought it, nor should I feel at

liberty to decline it, if conferred upon me by the voluntary suffrages of

my fellow citizens." Because the Democratic Party was splintered into

bitter factions, Polk promised to serve only one term if elected,

hoping that his disappointed rival Democrats would unite behind him

with the knowledge that another candidate would be chosen in four years. Polk's

Whig opponent in the 1844

presidential election was Henry Clay of Kentucky. (Incumbent

Whig President John Tyler

— a former Democrat — had become estranged from the Whigs and was not

nominated for a second term.) The question of the annexation of

Texas,

which was at the forefront during the Democratic Convention, again

dominated the campaign. Polk was a strong proponent of immediate

annexation, while Clay seemed more equivocal and vacillating. Another

campaign issue, also related to westward expansion, involved the Oregon Country,

then under the joint occupation of the United States and Great Britain.

The Democrats had championed the cause of expansion, informally linking

the controversial Texas annexation issue with a claim to the entire

Oregon Country, thus appealing to both Northern and Southern

expansionists. (The slogan "Fifty-Four Forty or Fight," often

incorrectly attributed to the 1844 election, did not appear until

later.)

Polk's consistent support for westward expansion — what Democrats would

later call "Manifest

Destiny" — likely played an important role in his victory, as

opponent Henry Clay hedged his position. In the

election, Polk and his running mate, George M. Dallas,

won in the South and West,

while Clay drew support in the Northeast.

Polk lost his home state of Tennessee, but he won the crucial state of

New York (with the support of many Van Buren supporters, since it was

his home state), where Clay lost supporters to the third-party candidate James G. Birney of

the Liberty Party, who was antislavery. Also contributing to Polk's

victory was the support of new immigrant voters, who were angered at

the Whigs' policies. Polk won the popular vote by a margin of about

39,000 out of 2.6 million, and took the Electoral College with 170

votes to Clay's 105. Polk won 15 states, while Clay

won 11. Polk is the only Speaker of the House of

Representatives to be elected President of the United States. When

he took office on March 4, 1845, Polk, at 49, became the youngest man

at the time to assume the presidency. According to a story told decades

later by George Bancroft,

Polk set four clearly defined goals for his administration: Pledged

to serve only one term, he accomplished all these objectives in just

four years. By linking acquisition of new lands in Oregon (with no

slavery) and Texas (with slavery), he hoped to satisfy both North and

South. During his presidency James

K. Polk was known as "Young Hickory", an allusion to his mentor Andrew

Jackson, and "Napoleon of the Stump" for his speaking skills. In

1846, Congress approved the Walker Tariff (named after Robert J. Walker,

the Secretary of

the Treasury), which represented a substantial reduction of the

high Whig backed Tariff of 1842.

The new law abandoned ad valorem tariffs;

instead, rates were made independent of the monetary value of the

product. Polk's actions were popular in the South and West; however,

they earned him the enmity of many protectionists in Pennsylvania. In

1846, Polk approved a law restoring the Independent Treasury System,

under which government funds were held in the Treasury rather than in

banks or other financial institutions. This established independent

treasury deposit offices, separate from private or state banks, to

receive all government funds. During

his presidency, many abolitionists harshly criticized him as an

instrument of the "Slave Power",

and claimed that the expansion of slavery lay behind his support for the annexation

of Texas and

later war with Mexico. Polk stated in his diary that

he believed slavery could not exist in the territories won from Mexico, but refused to endorse the Wilmot Proviso that would forbid it there.

Polk argued instead for extending the Missouri

Compromise line

to the Pacific Ocean, which would prohibit the expansion of slavery

above 36° 30' west of Missouri,

but allow it below that line if approved by eligible voters in the

territory. William

Dusinberre has

argued that Polk's diary, which he kept during his presidency, was

written for later publication, and does not represent Polk's real

policy. Polk

was a slaveholder for his entire life. His father, Alabaster Polk, had

left Polk more than 8,000 acres (32 km²) of land, and divided

about 53 slaves to his widow and children after Samuel died. James

inherited twenty of his father's slaves, either directly or from

deceased brothers. In 1831, he became an absentee cotton planter,

sending slaves to clear plantation land that his father had left him

near Somerville,

Tennessee.

Four years later Polk sold his Somerville plantation and, together with

his brother-in-law, bought 920 acres (3.7 km²) of land, a

cotton plantation near Coffeeville,

Mississippi.

He ran this plantation for the rest of his life, eventually taking it

over completely from his brother-in-law. Polk rarely sold slaves,

although once he became President and could better afford it, he bought

more. Polk's will stipulated that their slaves were to be freed after

his wife Sarah had died. However, the 1863

Emancipation Proclamation and the 1865 Thirteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution freed all remaining slaves in rebel

states long before the death of his wife in 1891. Polk

was committed to expansion: Democrats believed that opening up more

land for yeoman farmers was critical for the success of republican

virtue.

Like most Southerners, he supported the annexation of Texas. To balance

the interests of North and South, he wanted to acquire the Oregon

Country (present day Oregon, Washington, Idaho,

and British Columbia)

as well. He sought to purchase California, which Mexico had neglected. Polk put

heavy pressure on Britain to resolve the Oregon boundary

dispute.

Since 1818, the territory had been under the joint occupation and

control of Great Britain and the United States. Previous U.S.

administrations had offered to divide the region along the 49th parallel,

which was not acceptable to Britain, as they had commercial interests

along the Columbia River.

Although the Democratic platform asserted a claim to the entire region,

Polk was prepared to quietly compromise. When the British again refused

to accept the 49th parallel boundary proposal, Polk broke off

negotiations and returned to the Democratic platform "All

Oregon" demand (which called for all of Oregon up to the 54 - 40 line

that marked the southern boundary of Russian Alaska). "54 - 40 or

fight!"

now became a popular rallying cry among Democrats. Polk wanted territory, not war, so he

compromised with the British Foreign Secretary, Lord

Aberdeen. The Oregon

Treaty of

1846 divided the Oregon Country along the 49th parallel, the original

American proposal. Although there were many who still clamored for the

whole of the territory, the treaty was approved by the Senate. By

settling for the 49th parallel, Polk angered many midwestern Democrats.

Many of these Democrats believed that Polk had always wanted the

boundary at the 49th, and that he had fooled them into believing he

wanted it at the 54th

parallel.

The portion of Oregon territory acquired by the United States later

formed the states of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho, and parts of the

states of Montana and Wyoming. President

Tyler despised Polk, both as a person and politician. Upon hearing of

Polk's election to office, Tyler urged Congress to pass ajoint resolution admitting Texas to the Union;

Congress complied on February 28, 1845. Texas promptly accepted the

offer and officially became a state on December 29, 1845. The

annexation angered Mexico,

which had lost Texas in

1836.

Mexican politicians had repeatedly warned that annexation would lead to

war. Nonetheless, Polk declared in his inaugural address, just days

after the resolution passed Congress, that the decision of annexation

belonged exclusively to Texas and the United States. After

the Texas annexation, Polk turned his attention to California, hoping

to acquire the territory from Mexico before any European nation did so.

The main interest was San Francisco

Bay as an access

point for trade with Asia. In 1845, he sent diplomat John Slidell to Mexico to purchase

California and New Mexico for

$24 – 30 million. Slidell's arrival caused political turmoil in Mexico

after word leaked out that he was there to purchase additional

territory and not to offer compensation for the loss of Texas. The

Mexicans refused to receive Slidell, citing a technical problem with

his credentials. In January 1846, to increase pressure on Mexico to

negotiate, Polk sent troops under General Zachary Taylor into

the area between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande —

territory that was claimed by both the U.S. and Mexico.

Slidell

returned to Washington in May 1846, having been rebuffed by the Mexican

government. Polk regarded this treatment of his diplomat as an insult

and an "ample cause of war", and he prepared to ask Congress

for a declaration of war. Meanwhile Taylor crossed the Rio Grande River

and briefly occupied Matamoros,

Tamaulipas.

Taylor continued to blockade ships from entering the port of Matamoros.

Mere days before Polk intended to make his request to Congress, he

received word that Mexican forces had crossed the Rio Grande area and

killed eleven American soldiers. Polk then made this the casus belli,

and in a message to Congress on May 11, 1846, he stated that Mexico had

"invaded our territory and shed American blood upon the American soil."

Some Whigs in Congress, such as Abraham Lincoln,

challenged Polk's version of events,

but Congress overwhelmingly approved the declaration of war. Many Whigs

feared that opposition would cost them politically by casting

themselves as unpatriotic for not supporting the war effort. In the House, antislavery Whigs led by John

Quincy Adams voted against the war; among Democrats,

Senator John

C. Calhoun was the most notable opponent of the

declaration. Polk

selected the top generals and set the overall military strategy of the

war. By the summer of 1846, American forces under General Stephen W.

Kearny had captured New Mexico. Meanwhile, Army captain John C.

Frémont led

settlers in northern California to overthrow the Mexican garrison in

Sonoma (in the Bear Flag Revolt).

General Zachary Taylor, at the same time, was having success on the Rio

Grande, although Polk did not reinforce his troops there. The United

States also negotiated a secret arrangement with Antonio

López de Santa Anna,

the Mexican general and dictator who had been overthrown in 1844. Santa

Anna agreed that, if given safe passage into Mexico, he would attempt

to persuade those in power to sell California and New Mexico to the

United States. Once he reached Mexico, however, he reneged on his

agreement, declared himself President, and tried to drive the American

invaders back. Santa Anna's efforts, however, were in vain, as Generals

Taylor and Winfield Scott destroyed

all resistance. Scott captured Mexico City in September 1847, and

Taylor won a series of victories in northern Mexico. Even after these

battles, Mexico did not surrender until 1848, when it agreed to peace

terms set out by Polk. Polk

sent diplomat Nicholas Trist to

negotiate with the Mexicans. Lack of progress prompted the President to

order Trist to return to the United States, but the diplomat ignored

the instructions and stayed in Mexico to continue bargaining. Trist

successfully negotiated theTreaty of

Guadalupe Hidalgo in

1848, which Polk agreed to ratify, ignoring calls from Democrats who

demanded the annexation of the whole of Mexico. The treaty added 1.2

million square miles (3.1 million square kilometers) of territory to

the United States; Mexico's size was halved, while that of the United

States increased by a third. California, Nevada, Utah,

most of Arizona,

and parts of New Mexico, Colorado and Wyoming were

all included in the Mexican Cession. The treaty also recognized the

annexation of Texas and acknowledged American control over the disputed

territory between the Nueces River and

the Rio Grande. Mexico, in turn, received the sum of $15 million. The

war claimed fewer than 20,000 American lives but over 50,000 Mexican

ones. It may have cost the United

States $100 million. Finally, the Wilmot Proviso injected

the issue of slavery in the new territories, even though Polk had

insisted to Congress and in his diary that this had never been a war

goal. The

treaty, however, needed ratification by the Senate. In March 1848, the

Whigs, who had been so opposed to Polk's policy, suddenly changed

position. Two-thirds of the Whigs voted for Polk's treaty. This ended

the war and legalized the acquisition of the territories. The

war had serious consequences for Polk and the Democrats. It gave the

Whig Party a unifying message of denouncing the war as an immoral act

of aggression carried out through abuse of power by the president. In

the 1848 election, however, the Whigs nominated General Zachary

Taylor,

a war hero, and celebrated his victories. Taylor refused to criticize

Polk. As a result of the strain of managing the war effort directly and

in close detail, Polk's health markedly declined toward the end of his

presidency. One

of Polk's last acts as President was to sign the bill creating the Department of

the Interior (March

3, 1849). This was the first new cabinet position created since the

early days of the Republic. Polk's

time in the White House took

its toll on his health. Full of enthusiasm and vigor when he entered

office, Polk left on March 4, 1849, exhausted by his years of public

service. He lost weight and had deep lines on his face and dark circles

under his eyes. He is believed to have contracted cholera in New Orleans, Louisiana,

on a goodwill tour of the South. He

died at his new home, Polk Place, in Nashville,

Tennessee,

at 3:15 p.m. on June 15, 1849, three months after leaving office. He

was buried on the grounds of Polk Place. Polk's devotion to his wife is

illustrated by his last words: "I love you, Sarah. For all eternity, I

love you." She lived at Polk Place for

over forty years after his death. She died on

August 14, 1891. Polk was also survived by his mother, Jane Knox Polk. Polk had the

shortest retirement of

all Presidents at 103 days. He was the youngest former president to die

in retirement at the age of 53. He and his wife are buried in a tomb on

the grounds of the Tennessee

State Capitol in Nashville, Tennessee. The tomb was

moved to this location in 1893 after his home at Polk

Place was demolished. Polk's

historic reputation was largely formed by the attacks made on him in

his own time; the Whigs claimed that he was drawn from a well deserved

obscurity; Senator Tom Corwin of Ohio remarked "James K.

Polk, of Tennessee? After

that,

who is safe?" The Republican historians of the nineteenth century

inherited this view. Polk was a compromise between the Democrats of the

North, like David Wilmot and Silas Wright,

and the plantation owners who were led by John C. Calhoun;

the northern Democrats thought that when they did not get their way, it

was because he was the tool of the slaveholders, and the conservatives

of the South insisted that he was the tool of the northern Democrats.

These views were long reflected in the historical literature, until Arthur M.

Schlesinger, Jr and Bernard De Voto argued that Polk was

nobody's tool, but set his own goals and achieved them.

Polk

is now recognized, not only as the strongest president between Jackson

and Lincoln, but the president who made the United States a

coast-to-coast nation. When historians began ranking the presidents in

1948, Polk ranked 10th in Arthur M.

Schlesinger’s poll and has subsequently ranked 8th in

Schlesinger’s 1962 poll, 11th

in the Riders - McIver Poll (1996), 11th in the most recent Siena Poll

(2002), 9th in the most recent Wall

Street Journal Poll

(2005), and 12th in the latest C-Span Poll (2009). Polk

biographers over the years have sized up the magnitude of Polk’s

achievements and his legacy, particularly his two most recent. “There

are three key reasons why James K. Polk deserves recognition as a

significant and influential American president,” Walter Borneman wrote.

“First, Polk accomplished the objectives of his presidential term as he

defined them; second, he was the most decisive chief executive prior to

the Civil War;

and third, he greatly expanded the executive power of the presidency,

particularly its war powers, its role as commander in chief, and its

oversight of the executive branch." President Harry S. Truman summarized this view by saying

that Polk was "a great president. Said what he intended to do and did

it." While

Polk’s legacy thus takes many forms, the most outstanding is the map of

the continental United States, whose landmass he increased by a third.

“To look at that map,” Robert Merry concluded, “and to take in the

western and southwestern expanse included in it, is to see the

magnitude of Polk’s presidential accomplishments.” Nevertheless,

the Polk's aggressive expansionism has been criticized on ethical

grounds. In a sentence, he believed in "Manifest Destiny" to a much

greater extent than most. In reference to the Mexican - American War,

General Ulysses

S. Grant stated

that "I was bitterly opposed to the [Texas annexation], and to this day

regard the war, which resulted, as one of the most unjust ever waged by

a stronger against a weaker nation. It was an instance of a republic

following the bad example of European monarchies, in not considering

justice in their desire to acquire additional territory." Whig politicians, including David

Wilmot, Abraham

Lincoln and John

Quincy Adams contended that

the Texas

Annexation and the Mexican

Cession enhanced the pro-slavery

factions of the United States. Unsatisfactory

conditions pertaining to the status of slavery in the territories

acquired during the Polk administration lead to the Compromise

of 1850, one of the primary

factors in the establishment of the Republican

Party and later the beginning of the American

Civil War.

In

the summer of 1848, President Polk authorized his ambassador to Spain, Romulus

Mitchell Saunders, to negotiate the purchase of Cuba and

offer Spain up to $100 million, an astounding sum of money at the time

for one territory, equivalent to $2.51 billion in present day

terms. Cuba

was close to the United States and had slavery, so the idea appealed to

Southerners but was unwelcome in the North. But Spain was still making

huge profits in Cuba (notably in sugar, molasses, rum, and tobacco),

and the Spanish government rejected Saunders' overtures.