<Back to Index>

- Explorer Jean Chardin, 1643

- Author Peter Andreas Heiberg, 1758

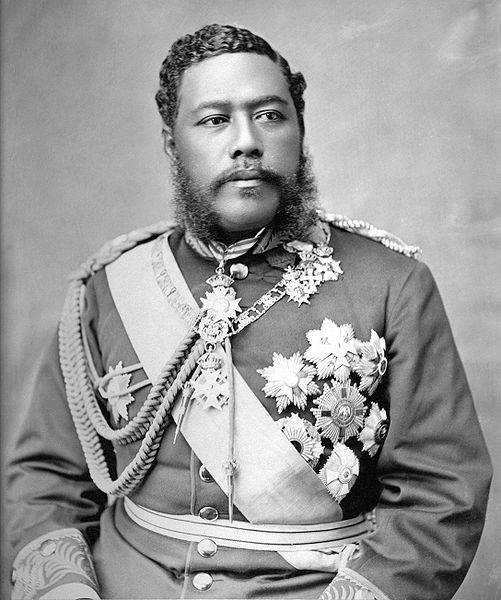

- King of the Wawaiian Islands Kalākaua, 1836

PAGE SPONSOR

Kalākaua, born David Laʻamea Kamanakapuʻu Mahinulani Nalaiaehuokalani Lumialani Kalākaua and sometimes called The Merrie Monarch (November 16, 1836 - January 20, 1891), was the last reigning king of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi. He reigned from February 12, 1874 until his death in San Francisco, California, on January 20, 1891.

Kalākaua was the first surviving son of his father High Chief Caesar Kaluaiku Kapaʻakea and his mother High Chiefess Analea Keohokālole. He was the younger brother of Moses Kapaakea and James Kaliokalani and older brother of Lydia Kamakaeha, Anna Kaiulani, Kaiminaauao, Kinini Kapaakea, Miriam Likelike, and William Pitt Leleiohoku II. Although he was promised in hanai to Kuini Liliha, Kaahumanu II gave her to the high chiefess Haaheo Kaniu and her husband Kinimaka instead. Haaheo died in 1843; she bequeathed all her properties to him. His guardianship was entrusted in his hanai father, who was a chief of lesser rank, he took Kalakaua to live in Lahaina. Kinimaka would later remarry Pai, a Tahitian woman, who treated Kalakaua as her own until the birth of her own son. When Kalākaua was four, he returned to Oahu to begin his education at the Chiefs' Children's School. At the school, Kalākaua became fluent in English and the Hawaiian language.

He began studying law at the age of 16. His various government

positions, however, prevented him from fully completing his legal

training. Instead, by 1856, the young Hawaiian was a major on the staff of King Kamehameha IV.

He had also led a political organization known as the Young Hawaiians;

the group’s motto was "Hawaii for the Hawaiians." In addition to his

military duties, Kalākaua served in the Department of the Interior and,

in 1863, was appointed postmaster general. King Kamehameha V, the last monarch of the Kamehameha dynasty,

died on December 12, 1872 without naming a successor to the throne.

Under the Kingdom's constitution, if the King did not appoint a

successor, a new king would be appointed by the legislature. There were

several candidates for the Hawaiian throne. However, the contest was

centered on two high-ranking aliʻi, or chiefs: William C. Lunalilo and

Kalākaua. Lunalilo was more popular, partially because he was a

higher ranking chief than Kalākaua and was the immediate cousin of the

Kamehameha V. Lunalilo was also the more liberal of

the two — he promised to amend the constitution to give the people a

greater voice in the government. Many believed that the government

should simply declare Lunalilo as the king. Lunalilo, however, refused

to allow this to be done and insisted that everyone in the kingdom

should take part in an election for the office of the king. Kalākaua

published a proclamation written in a Hawaiian poetic style. Here is an

excerpt: "O my people! My countrymen of old! Arise! This is the voice!" Kalākaua was much more conservative than

his opponent, Lunalilo. At the time, foreigners dominated the Hawaiian

government. Kalākaua promised to put native Hawaiians back into the

Kingdom's government. He also promised to amend the Kingdom's constitution. On

January 1, 1873, a popular election was held for the office of King of

Hawaii. Lunalilo won with an overwhelming majority. The next day, the

legislature confirmed the popular vote and elected Lunalilo

unanimously. Kalākaua conceded. Lunalilo died on February 3, 1874, and Kalākaua was elected to replace him, supported by the legislature although many of the populace, mainly the native Hawaiian and British subjects in the Kingdom, preferred Queen Dowager Emma, who stood against him. Upon ascending the throne, Kalākaua named his brother, William Pitt Leleiohoku, as his heir, putting an end to the era of elected kings in Hawaiʻi. Kalākaua

began his reign with a tour of the Hawaiian islands. This improved his

popularity. In October 1874, Kalākaua sent representatives to the United States to negotiate a reciprocity treaty to help end a depression that was ongoing in Hawaiʻi. In November, Kalākaua himself traveled to Washington, D.C. to meet President Ulysses S. Grant. An agreement was reached and the treaty was signed on January 30, 1875. The treaty allowed certain Hawaiian goods, mainly sugar and rice, to be admitted into the United States tax-free. During the early part of Kalākaua's reign, the king made full use of his power to appoint and dismiss cabinets. King Kalākaua believed in the hereditary right of the aliʻi

to rule. Kalākaua continually dismissed cabinets and appointed new

ones. This drew criticism from people of the "Missionary Party" who

wanted to reform Hawaiian government based on the model of the United

Kingdom's constitutional monarchy where

the monarch had very little real power over the government but had a

position of great dignity and was the head of state. The party believed

the legislature should control the cabinet ministers rather than the

king. This struggle continued throughout Kalākaua's reign.

In 1881, King Kalākaua left Hawaiʻi

on a trip around the world to study the matter of immigration and to

improve foreign relations. He also wanted to study how other rulers

ruled. In his absence, his sister and heir, Princess Liliʻuokalani, ruled as regent (Prince Leleiohoku, the former heir, had died in 1877). The King first traveled to San Francisco where he was given a royal welcome. Then he sailed to the Empire of Japan where he met with the Meiji Emperor. He continued through Qing Dynasty China, Siam under King Chulalongkorn (Rama V), Burma, British Raj India, Egypt, Italy, Belgium, the German Empire, Austria - Hungary, the French Third Republic, Spain under the Restoration, Portugal, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and back through the United States before returning to Hawaiʻi. During this trip, he met with many other crowned heads of state, including Pope Leo XIII, Umberto I of Italy, Tewfik, Viceroy of Egypt, William II of Germany, Rama V of Siam, U.S. President Chester Arthur, and Victoria of the United Kingdom. In this, he became the first king to travel around the world. Kalākaua also built ʻIolani Palace,

the only royal palace that exists on American soil today, at a cost of

$300,000 — a sum unheard of at the time. Many of the furnishings in the

palace were ordered by Kalākaua while he was in Europe. Kalākaua decided to erect the Kamehameha Statue in recognition of Kamehameha I, the first king of the whole Hawaiian Islands. The original statue was lost when the ship carrying it sank near the Falkland Islands,

so a replacement was ordered and unveiled by the king in 1883. The

original statue was later salvaged, repaired and sent to Hawaii in

1912. A third statue was erected in 1969 and is currently the only

statue in the United States Capitol that commemorates a native Hawaiian. King Kalākaua is said to have wanted to build a Polynesian Empire.

In 1886, legislature granted the government $30,000 for the formation

of a Polynesian confederation. The King sent representatives to Sāmoa, where Malietoa Laupepa agreed

to a confederation between the two kingdoms. This confederation did not

last very long, however, since King Kalākaua lost power the next year

to the Bayonet Constitution, and thus a reformist party came into power that ended the alliance. By

1887, the Missionary party had grown very frustrated with Kalākaua.

They blamed him for the Kingdom's growing debt and accused him of being

a spendthrift. Some foreigners wanted to force King Kalākaua to

abdicate and put his sister Liliʻuokalani onto the throne, while others wanted to end the monarchy altogether and annex the islands to the United States.

The people who favored annexation formed a group called the Hawaiian

League. In 1887, members of the League armed with guns assembled

together. The members of the league forced him at gun point to sign the

new constitution. This new constitution, nicknamed the Bayonet Constitution of

1887, removed much of the King's executive power and deprived most

native Hawaiians of their voting rights. 75% of ethnic Hawaiians could

not vote at all because of the gender, literacy, property, and age

requirements. However, because of the racial disenfranchisement of

Asians, ethnic Hawaiians still amounted to about two-thirds of the

electorate for representatives and about one-third of the electorate

for Nobles. The rest of the voters were male residents of European or

American ancestry. It is important to note that historically voting

rights were not granted to all citizens in the Kingdom nor in other

countries. There were property, racial, gender, age, and literacy

requirements. Even voting rights in the United States were

restricted during this period of history. The legislature was now able

to override a veto by the King, and the King was no longer allowed to

take action without approval of the cabinet. The House of Nobles, the

house of legislature appointed by the King, was to be elected. It also

inserted a provision that allowed non-Hawaiian citizens to vote. A

counter revolution, led by Robert Wilcox, aimed at restoring the King's power, failed. By 1890, the King's health began to fail. Under the advice of his physician, he traveled to San Francisco. His health continued to worsen, and he died on January 20, 1891 at the Palace Hotel in

San Francisco. His final words were, "Tell my people I tried." His

remains were returned to Honolulu aboard the American cruiser USS Charleston (C-2). Because he and his wife, Queen Kapiʻolani, did not have any children, Kalākaua's sister, Liliʻuokalani, succeeded him to the Hawaiian throne. King

Kalākaua earned the nickname "the Merrie Monarch," because of his love

of joyful elements of life. This was a reference to the nickname of the

pleasure loving Charles II of England. Under his reign, hula was revived, which had been banned by Queen Ka'ahumanu in 1830 after converting to Christianity. Today, his name lives on in the Merrie Monarch Festival, a hula festival named in his honor. He is also known to have revived the Hawaiian martial art, Lua, and surfing. He and his brother and sisters were known as the "Royal Fours" for their musical talents. He wrote Hawaii Ponoi, which is the state song of Hawaii today. King Kalākaua's ardent support of the then newly introduced ukulele as a Hawaiian instrument led to its becoming symbolic of Hawaii and Hawaiian culture. In Waikiki, an avenue is named after him, "Kalākaua Avenue"; this is the main avenue of Waikiki taking people from the Ala Wai Canal to Waikiki beach as it continues almost until the Diamond Head crater. In 2003 the historic former federal building was renamed the King David Kalakaua Building after being purchased by the state and renovated.

"Ho! all ye tribes! Ho! my own ancient people! The people who took hold and built up the Kingdom of Kamehameha."

"Arise! This is the voice."

"Let me direct you, my people! Do nothing contrary to the law or against the peace of the Kingdom."

"Do not go and vote."

"Do

not be led by the foreigners; they had no part in our hardships, in

gaining the country. Do not be led by their false teachings."