<Back to Index>

- Physicist Johannes Diderik van der Waals, 1837

- Sculptor Kaspar Clemens von Zumbusch, 1830

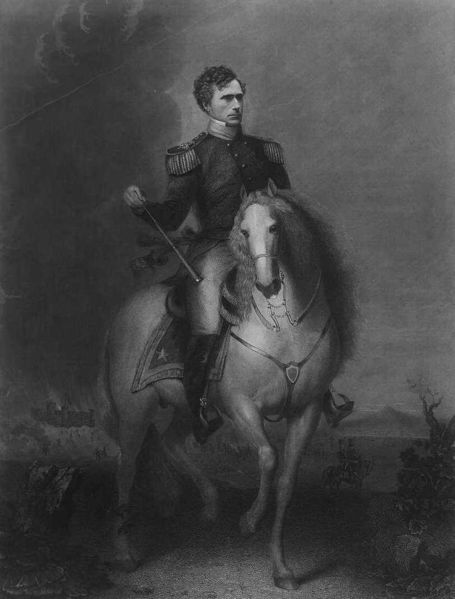

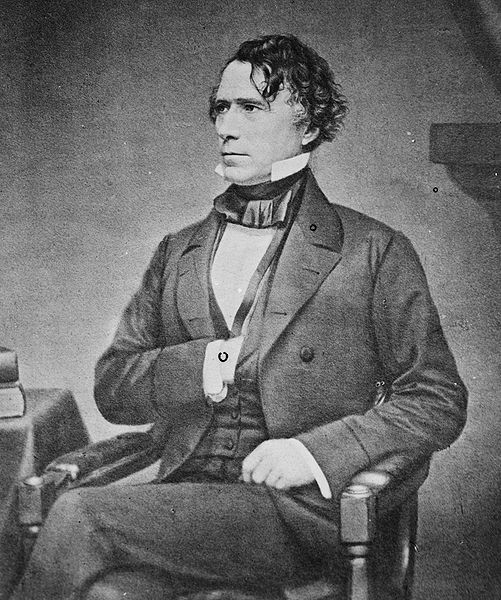

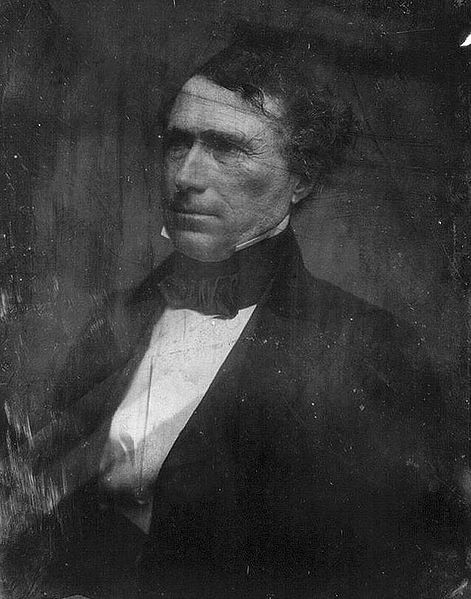

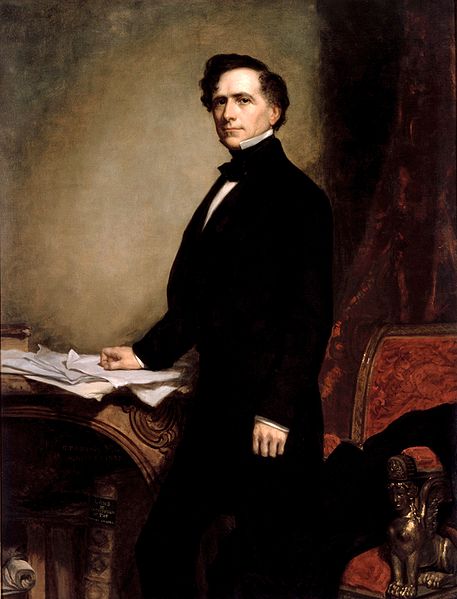

- 14th President of the United States Franklin Pierce, 1804

PAGE SPONSOR

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804 – October 8, 1869), an American politician and lawyer, was the 14th President of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. To date, he is the only President from New Hampshire.

Pierce was a Democrat and a "doughface" (a Northerner with Southern sympathies) who served in the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate. Later, Pierce took part in the Mexican - American War and became a brigadier general. His private law practice in his home state, New Hampshire, was so successful that he was offered several important positions, which he turned down. Later, he was nominated as the party's candidate for president on the 49th ballot at the 1852 Democratic National Convention. In the presidential election, Pierce and his running mate William R. King won by a landslide in the Electoral College. They defeated the Whig Party ticket of Winfield Scott and William A. Graham by a 50% to 44% margin in the popular vote and 254 to 42 in the electoral vote.

His amiable personality and handsome appearance caused him to make many friends, but he suffered tragedy in his personal life. As president, he made many divisive decisions which were widely criticized and earned him a reputation as one of the worst presidents in U.S. history. Pierce's popularity in the North declined sharply after he came out in favor of the Kansas - Nebraska Act, repealing the Missouri Compromise and renewed the debate over expanding slavery in the West. Pierce's credibility was further damaged when several of his diplomats issued the Ostend Manifesto. Historian David Potter concludes that the Ostend Manifesto and the Kansas - Nebraska Act were "the two great calamities of the Franklin Pierce administration.... Both brought down an avalanche of public criticism." More importantly, says Potter, they permanently discredited Manifest Destiny and "popular sovereignty" as political doctrines.

Abandoned by his party, Pierce was not renominated to run in the 1856 presidential election and was replaced by James Buchanan as the Democratic candidate. After losing the Democratic nomination, Pierce continued his lifelong struggle with alcoholism as his marriage to Jane Means Appleton Pierce fell apart. His reputation was destroyed during the American Civil War when he declared support for the Confederacy, and personal correspondence between Pierce and Confederate President Jefferson Davis was leaked to the press. He died in 1869 from cirrhosis.

Philip B. Kunhardt and Peter W. Kunhardt reflected the views of many historians when they wrote in The American President that Pierce was "a good man who didn't understand his own shortcomings. He was genuinely religious, loved his wife and reshaped himself so that he could adapt to her ways and show her true affection. He was one of the most popular men in New Hampshire, polite and thoughtful, easy and good at the political game, charming and fine and handsome. However, he has been criticized as timid and unable to cope with a changing America."

Franklin Pierce was born in a log cabin in Hillsborough, New Hampshire, on November 23, 1804, the first U.S. president born in the nineteenth century. The site of his birth is now under Franklin Pierce Lake. Pierce's father was Benjamin Pierce, a frontier farmer who became a Revolutionary War soldier, a state militia general, and a two-time Democratic - Republican governor of New Hampshire. He was a direct descendant of Thomas Pierce (1623 – 1683), who was born in Norwich, Norfolk, England and settled in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Franklin Pierce's mother was Anna B. Kendrick. The fifth of eight children, he had four brothers and three sisters. Former First Lady of the United States Barbara Bush is a distant cousin. Pierce attended school at Hillsborough Center and moved to the Hancock Academy in Hancock at the age of 11; he transferred to Francestown Academy

in the spring of 1820. Friends recalled that just after he entered the

school, he became homesick and returned home barefoot. His father put

him in a wagon, drove him half way back to the academy, and left him on

the roadside, never saying a word. The boy trudged the remaining seven miles back to school. Later that year he transferred to Phillips Exeter Academy to prepare for college. In fall 1820, he entered Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, where he joined literary, political, and debating clubs.

There he met writer Nathaniel Hawthorne, with whom he formed a lasting friendship, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. He also met Calvin E. Stowe, Seargent S. Prentiss, and his future political rival, John P. Hale, when he joined the Athenian Society, a group of students with progressive political leanings. In

his second year of college his grades were the lowest of his class, but

he worked to improve them and ranked third among his classmates when he

graduated in 1824. In 1826 he entered a law school in Northampton, Massachusetts, studying under Governor Levi Woodbury, and later Judges Samuel Howe and Edmund Parker, in Amherst, New Hampshire. He was admitted to the bar and began a law practice in Concord, New Hampshire, in 1827. After

graduating from college, Pierce entered politics and rose to a central

position in the Democratic party of New Hampshire and became a member

of the Concord Regency leadership group. In 1828 he was elected to the lower house of the New Hampshire General Court, the New Hampshire House of Representatives. He served in the State House from 1829 to 1833, and as Speaker from 1832 to 1833. Pierce served in the state legislature of New Hampshire while his father was governor. In 1832, Pierce was elected as a Democrat to the 23rd and 24th Congresses (March 4, 1833 – March 4, 1837). He was only 27 years old, the youngest U.S. Representative at the time. In 1836, he was elected by the New Hampshire General Court as a Democrat to the United States Senate, serving from March 4, 1837, to February 28, 1842, when he resigned. He was chair of the U.S. Senate Committee on Pensions during the 26th Congress. After his service in the Senate, Pierce resumed the practice of law in Concord with his partner Asa Fowler. He was the United States Attorney for the District of New Hampshire from 1845 to 1847. He refused the Democratic nomination for Governor of New Hampshire and declined the appointment as Attorney General of the United States tendered by President James K. Polk. On November 19, 1834, Pierce married Jane Means Appleton (1806 – 63), the daughter of a former president of Bowdoin College. Appleton was Pierce's opposite. Born into an aristocratic Whig family, she was shy, often ill, deeply religious, and pro-temperance.

They had three children, all of whom died in childhood. The last child,

who lived the longest, was killed in a train wreck at the early age of

11. None lived to see their father become president. Jane was never happy with her husband's involvement in the political world. She took no pleasure from life in Washington, D.C., and encouraged Pierce to resign his Senate seat and return to New Hampshire, which he did in 1842. After the gruesome death of her last child, shortly before Pierce's inauguration, she was overcome with melancholia and

distanced herself from her husband during his presidency. She became

known as "the shadow of the White House." She was deeply religious and

blamed the death of their last child, Benjamin as God's anger brought

on by her husband's political life. He enlisted in the volunteer services during the Mexican - American War and

rose to the rank of colonel. In March 1847, he was appointed brigadier

general of volunteers and took command of a brigade of reinforcements

for Winfield Scott's army marching on Mexico City. His brigade was designated the 1st Brigade in the newly created 3rd Division and joined Scott's army in time for the Battle of Contreras. During the battle he was seriously wounded in the leg when he fell from his horse. He returned to his command the following day, but during the Battle of Churubusco the

pain in his leg became so great that he passed out and had to be

carried from the field. His political opponents used this against him,

claiming that he left the field because of cowardice instead of injury.

He returned to command and led his brigade throughout the rest of the

campaign, resulting in the capture of Mexico City.

Although he was a political appointee, he proved to have some skill as

a military commander. He returned home and served as president of the

New Hampshire state constitutional convention in 1850. At

the Democratic National Convention of 1852, Pierce was not a serious

candidate for the presidential nomination. He had no credentials as a

major political figure or leader, and had not held elective office for

the last ten years. The convention assembled on June 1 in Baltimore, Maryland, with four major contenders — Stephen A. Douglas, William L. Marcy, James Buchanan and Lewis Cass — for the nomination. Most of those who had left the party with Martin Van Buren to form the Free Soil Party had returned. To unite the various Democratic Party factions before voting on a nominee, delegates adopted a party platform that rejected further "agitation" over the slavery issue and supported the Compromise of 1850. When

the balloting for president began, the four candidates deadlocked, with

no candidate reaching even a simple majority, much less the required supermajority of

two thirds. On the thirty-fifth ballot, Pierce was put forth to break

the deadlock as a compromise candidate. Pierce's long career as a party

activist and consistent supporter of Democratic positions made him

popular among delegates. He had never fully explained his views on

slavery, allowing all factions to view him as reasonably acceptable.

His service in the Mexican - American War would allow the party to

portray him as a war hero. On June 5, delegates unanimously nominated Pierce on the 49th ballot. Alabama Senator William R. King was chosen as the nominee for Vice President. The United States Whig Party's candidate was general Winfield Scott of Virginia, under whom Pierce had served in the Mexican - American War; his running mate was Secretary of the Navy William A. Graham. Scott — nicknamed "Old Fuss and Feathers" — ran a blundering campaign. The

Whigs' platform was almost indistinguishable from that of the

Democrats, reducing the campaign to a contest between the personalities

of the two candidates and helping to drive voter turnout in the election to its lowest level since 1836.

Pierce's affable personality and lack of strongly held positions helped

him prevail over Scott, whose antislavery views hurt him in the South.

Pierce's military service effectively neutralized Scott's reputation as

a celebrated war hero. Irish Catholic support of the Democratic Party and disdain for the Whig Party also helped Pierce. The Democrats' slogan was "We Polked you in 1844; we shall Pierce you in 1852!" (a reference to the victory of James K. Polk in the 1844 election). This proved to be true, as Scott won only the states of Kentucky, Tennessee, Massachusetts, and Vermont.

The total popular vote was 1,601,274 to 1,386,580, or 50.9% to 44.1%.

Pierce won 27 of the 31 states, including Scott's home state of

Virginia. John P. Hale,

who like Pierce was from New Hampshire, was the nominee of the remnants

of the Free Soil Party, garnering 155,825 votes (5% of the total). The

1852 election was the last presidential contest in which the Whigs

fielded a candidate. The Kansas - Nebraska Act, passed in 1854, divided the Whigs. The Whig Party splintered and most of its adherents migrated to the nativist American Party Know Nothings, the Constitutional Union Party, and the newly formed Republican Party. At his inauguration, Pierce, at age 48, was the youngest President to have taken office, a record he would keep until Ulysses S. Grant took office in 1869 at 46 years old. Pierce

served as President from March 4, 1853, to March 4, 1857. He began his

presidency exhausted and in mourning. Two months before, on January 6,

1853, the President elect's family had boarded a train in Boston, and were trapped in their derailed car when it rolled down an embankment near Andover, Massachusetts. Pierce and his wife survived, merely shaken up, but saw their 11 year old son Benjamin crushed to death. Jane

Pierce viewed the train accident as a divine punishment for her

husband's pursuit and acceptance of high office. Pierce chose to "affirm"

his oath of office rather than swear it, becoming the first president

to do so; he placed his hand on a law book rather than on a Bible while

doing so. He was also the first president to recite his inaugural address from

memory. In it Pierce hailed an era of peace and prosperity at home and

urged a vigorous assertion of US interests in its foreign relations.

"The policy of my Administration," said the new president, The nation was enjoying economic growth and relative tranquillity, and the Compromise of 1850 calmed

the debate over slavery. When the issue flamed up early in his

administration, though, Pierce did little to cool the passions it

aroused, and sectional conflicts reignited. Pierce selected men of differing opinions for his Cabinet,

including colleagues he knew personally and Democratic politicians.

Many anticipated the diverse group would soon break up, but it remained

unchanged during Pierce's four-year term (as of 2009, the only

presidential cabinet to do so). In foreign policy, Pierce sought to

display a traditional Democratic assertiveness. Various interests

nursed ambitions to detach nearby Cuba from a weak and distant Spain,

open trade with a reclusive Japan, and gain the advantage over Britain

in Central America. Although the Perry Expedition to

Japan was a success, Pierce's leadership increasingly came into

question when poorly anticipated developments exposed failures of

Administration planning and consultation. Pierce's administration aroused sectional apprehensions when it pressured the United Kingdom to relinquish its interests along part of the Central American coast. Three US diplomats in Europe drafted a proposal to the president to purchase Cuba from Spain for $120 million (USD), and justify the "wresting" of it from Spain if the offer were refused. The publication of the Ostend Manifesto,

which had been drawn up on the instance of Pierce's Secretary of State,

provoked the scorn of Northerners who viewed it as an attempt to annex

a slave holding possession to bolster Southern interests. It helped

discredit the expansionist policies the Democratic Party had supported in the 1844 election. The Gadsden Purchase from Mexico similarly exposed the seething unresolved sectional conflicts inherent in national expansion. The greatest challenge to the country's equilibrium during the Pierce administration, though, was the passage of the Kansas - Nebraska Act in 1854. It repealed the Missouri Compromise and reopened the question of slavery in the West. This measure, sponsored by Senator Stephen A. Douglas, originated in a drive to promote a transcontinental railroad with a link from Chicago, Illinois, to California through Nebraska. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, advocate of a southern transcontinental route, had persuaded Pierce to send James Gadsden to Mexico to buy land for a southern railroad. He purchased the area now comprising southern Arizona and part of southern New Mexico for $10 million (USD), commonly known as the Gadsden Purchase. This became known as the greatest success of the Pierce presidency.

To

win Southern support for organizing Nebraska, Douglas added provision

declaring the Missouri Compromise to be invalid. The bill provided that

the residents of the new territories could decide the slavery question

for themselves. Although his cabinet had made other proposals, Douglas

and several southern Senators successfully persuaded Pierce to support

Douglas' plan. The passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act triggered a series of events that became known as Bleeding Kansas. Pro-slavery Border Ruffians, mostly from Missouri, illegally voted in a government that Pierce recognized, and Pierce called the Topeka Constitution, a shadow government set up by Free-Staters,

an act of "rebellion." Pierce continued to recognize the pro-slavery

legislature even after a congressional investigative committee found

its election illegitimate, and dispatched federal troops to break up a

meeting of the shadow government in Topeka. The

Act provoked outrage among northerners who saw Pierce as kowtowing to

slave holding interests, provided the impetus for the formation of the

Republican Party, and contributed to critical estimates of Pierce as

untrustworthy and easily manipulated. Having lost public confidence,

Pierce failed to receive the nomination by his party for a second term.

Pierce's hiring of a full time bodyguard - the first president to

do so - is testament to his ruined reputation. Pierce has been ranked among the least effective Presidents.

He was unable to steer a steady, prudent course that might have

sustained a broad measure of support. Having publicly committed himself

to an ill-considered position, he maintained it steadfastly, but at

disastrous cost to his reputation. After

losing the Democratic nomination for reelection in 1856, Pierce retired

and traveled with his wife overseas. He returned to the U.S. in 1859 in

time to comment on the growing sectional crisis between the South and

the North, often criticizing Northern abolitionists for encouraging

ugly feelings between the two sections. In 1860 many Democrats viewed

Pierce as a solid compromise choice for the presidential nomination,

uniting both Northern and Southern wings of the party, but Pierce declined to run. During

the Civil War, Pierce attacked Lincoln for his order suspending habeas

corpus. Pierce argued that even in a time of war, the country should

not abandon its protection of civil liberties. Pierce's stand won him admirers with the emerging Northern Peace Democrats, but enraged certain members of the Lincoln administration: in 1862

Secretary of State William Seward sent Pierce a letter accusing him of

being a member of the seditious Knights of the Golden Circle.

Outraged, Pierce responded and demanded that Seward put his response in

the official files of the State Department. When that didn't happen, a

Pierce supporter in the US Senate, Milton Latham of California, had the entire Seward - Pierce correspondence read into the Congressional Globe.

Nearly every Seward biographer has since considered the Pierce - Seward

exchange as a blot on the Secretary's otherwise notable career. In

1864, friends again put his name in play for the Democratic nomination,

but by a letter read out loud to the delegates, Pierce said he would

not run. The year before, Pierce's reputation was greatly damaged in the North during the aftermath of Vicksburg. Union Soldiers serving under General Hugh Ewing's command captured Confederate President Jefferson Davis' Fleetwood Plantation, and Ewing turned over Davis' personal correspondence to his brother-in-law William T. Sherman. However,

Ewing also sent copies of the letters to friends in Ohio. Those letters

revealed his deep friendship with Davis and his ambivalence about the

goals of the war. As early as 1860, Pierce had written to Davis about

"the madness of northern abolitionism." Another letter stated that he

would "never justify, sustain, or in any way or to any extent uphold

this cruel, heartless, aimless unnecessary war," and that "the true

purpose of the war was to wipe out the states and destroy property." Abolitionist author Harriet Beecher Stowe, who had long disliked Pierce, now referred to him as "the archtraitor." On

April 16, 1865, when news had spread of the murder of President

Lincoln, an angry mob of young teenagers gathered outside Pierce's home

in Concord. Earlier that day a different mob had thrown black paint on

the front porch of former President Millard Fillmore, who, like Pierce,

was also regarded as a Lincoln detractor. The crowd in Concord wanted

to know why Pierce's house was not dressed with black bunting and

American flags, the visual proof of grief being used that day by

millions of people across the country. Pierce came outside to confront

the crowd and said he, too, was saddened by Lincoln's passing. When a

voice in the crowd yelled out "Where is your flag?" Pierce became angry

and recalled his family's long devotion to the country, including both

his and his father's service in the military. He said he needed to

display no flag to prove that he was a loyal American. The crowd soon

quieted down and even cheered and applauded the former president as he

went back into his home. Franklin Pierce died in Concord, New Hampshire,

at 4:49 a.m. on October 8, 1869, at 64 years old. President Ulysses S.

Grant, who later defended Pierce's service in the Mexican War, declared

a day of national mourning. Newspapers across the country carried

lengthy front-page stories examining Pierce's colorful and

controversial career. He was interred in the Minot Enclosure in the Old North Cemetery of Concord. In his last will,

which he signed January 22, 1868, he left an unusually large number of

specific bequests to friends, family and neighbors, including the

children of Nathaniel Hawthorne. He left $1,000 in trust to the local

library. The interest was used to purchase books. He left gifts of

money, paintings, and other items to various people. The cane of General Lafayette was among the bequests. His nephew Frank Pierce received the residue. Places named after President Pierce: Franklin Pierce University in Rindge, New Hampshire, Franklin Pierce School District, and namesake high school in Parkland, Washington, Pierce Elementary School in Flint, Michigan, Pierce County in Washington, Nebraska, Georgia, and Wisconsin (But not in North Dakota), Franklin Pierce Law Center in Concord, New Hampshire, Mt. Pierce in the Presidential Range of the White Mountains, New Hampshire, Franklin Pierce Lake (a reservoir in New Hampshire which covers the site of the log cabin in which he was born), Pierceton, Indiana.