<Back to Index>

- Astronomer Anders Celsius, 1701

- Painter Leonard Tsuguharu Foujita, 1886

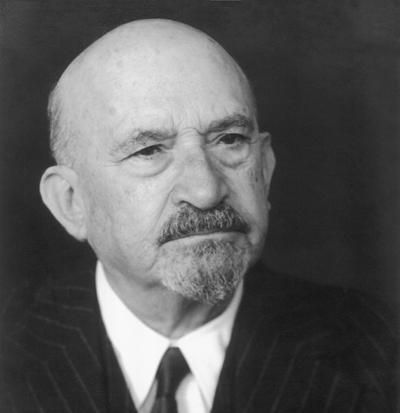

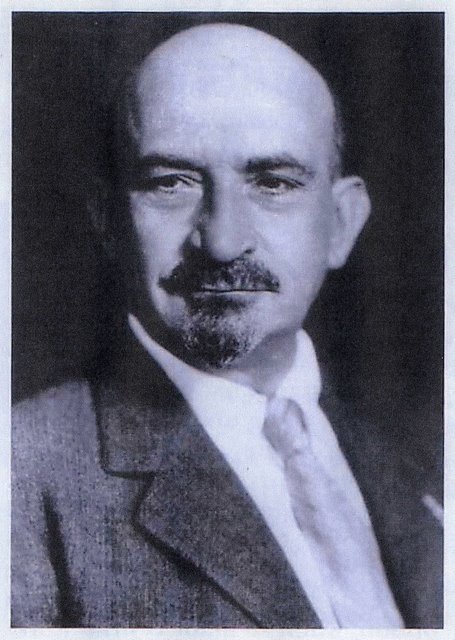

- 1st President of Israel Chaim Azriel Weizmann, 1874

PAGE SPONSOR

Chaim Azriel Weizmann, Hebrew: חיים עזריאל ויצמן, (27 November 1874 – 9 November 1952) was a Zionist leader, President of the Zionist Organization, and the first President of the State of Israel. He was elected on 1 February 1949, and served until his death in 1952. Weizmann was also a chemist who developed the ABE-process, which produces acetone through bacterial fermentation. He founded the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel.

Weizmann was born in the village of Motal near Pinsk in Belarus (at that time part of the Russian Empire). He was one of 15 children. His father was a timber merchant. Until the age of 11, he attended a traditional heder. At the age of 11, he entered high school in Pinsk. Weizmann studied chemistry at the Polytechnic Institute of Darmstadt, Germany, and University of Freiburg, Switzerland. In 1899, he was awarded a doctorate with honors. In 1901, he was appointed assistant lecturer at the University of Geneva and, in 1904, senior lecturer at the University of Manchester.

He was married to Vera Weizmann. His youngest son, Flight Lt Michael Oser Weizmann, serving as a pilot in the British No. 502 Squadron RAF, was killed when his plane was shot down over the Bay of Biscay. His nephew Ezer Weizman also became president of Israel. He is buried beside his wife in the garden of his home at the Weizmann estate, which is located on the grounds of Israel's science research institute, The Weizmann Institute of Science. Weizmann

missed the first Zionist conference, held in 1897 in Basel,

Switzerland, because of travel problems, but he attended each one thereafter. In 1902, he broke with Theodor Herzl and founded the Democratic Zionist Party. Beginning in 1903, he lobbied for the founding of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. A

proposal to this effect was adopted by the 11th World Zionist

Conference in 1913. In 1904, Weizmann became a chemistry professor at

the University of Manchester and soon became a leader among British Zionists. At that time in Manchester, Arthur Balfour was

a Conservative MP representing the district, as well as Prime Minister,

and the two met during one of Balfour's electoral campaigns. Balfour

supported the concept of a Jewish homeland, but felt that there would

be more support among politicians for the then current offer in Uganda.

Following mainstream Zionist rejection of that proposal, Weizmann was

credited later with persuading Balfour, then the Foreign Minister, for

British support to establish a Jewish homeland in Palestine, the

original Zionist demand. Weizmann first visited Jerusalem in 1907, and while there, he helped organize the Palestine Land Development Company as

a practical means of pursuing the Zionist dream. Although Weizmann was

a strong advocate for "those governmental grants which are necessary to

the achievement of the Zionist purpose" in Palestine, as stated at Basel, he persuaded many Jews not to wait for future events, stating: In 1917, he became president of the British Zionist Federation; he worked with Arthur Balfour to obtain the milestone Balfour Declaration, which stated in part that the British government "views with favour the

establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people ...

it being clearly understood...". A founder of so-called Synthetic Zionism,

Weizmann supported grass-roots colonization efforts as well as

high-level diplomatic activity. He was generally associated with the

centrist General Zionists and later sided with neither Labour Zionism on the left nor Revisionist Zionism on the right. In the 1917, expressed his view of Zionism in the following words, On January 3, 1919, he and the Hashemite Prince Faisal signed the Faisal - Weizmann Agreement attempting to establish favourable relations between Arabs and Jews in the Middle East. At the end of the month, the Paris Peace Conference decided

that the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire should be wholly

separated and the newly conceived mandate system applied to them. Shortly thereafter, both men made their statements to the conference. After

1920, he assumed leadership in the World Zionist movement, serving

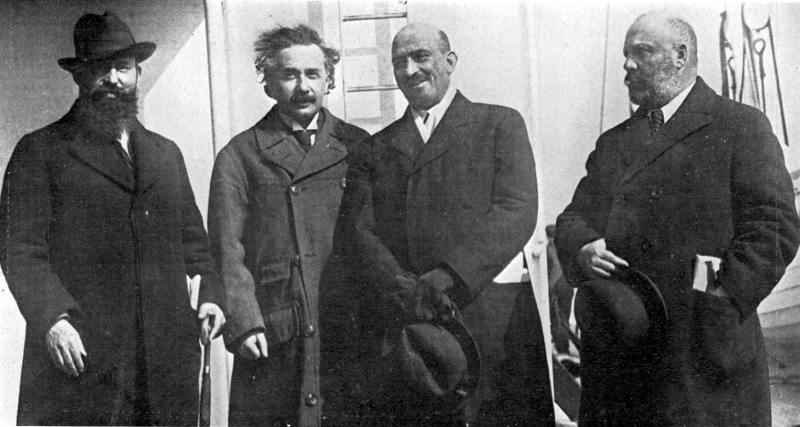

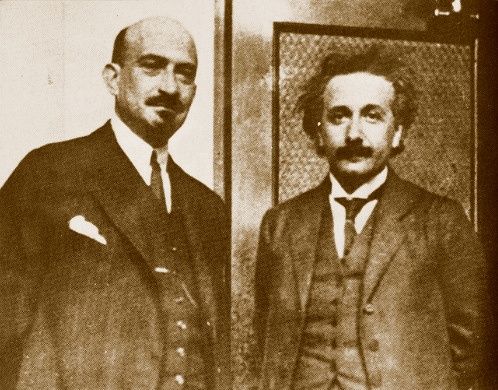

twice (1920 – 31, 1935 – 46) as president of the World Zionist Organization. In 1921, Weizmann went along with Albert Einstein for a fundraiser to establish the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. At this time, brewing differences over competing European and American

visions of Zionism, and its funding of development versus political

activities, caused Weizmann to clash with Louis Brandeis. During the war years, Brandeis headed the precursor of the Zionist Organization of America. Although Weizmann retained Zionist leadership, the

clash led to the departure from the movement of Brandeis and other

prominent leaders. By 1929, there were about 18,000 members left in the

ZOA, a massive decline from the high of 200,000 reached during the

Brandeis years. In 1936 he addressed the Peel Commission, set up by Stanley Baldwin, whose job it was to consider the working of the British Mandate of Palestine.

The Commission published a report that, for the first time, recommended

partition, but the proposal was declared unworkable and formally

rejected by the government. Weizmann and David Ben-Gurion accepted the

partition and its logic. This was the first official delineation and

declaration of a Zionist vision opting for an independent state with a

majority of Jewish population, along a new state with a vast Arab

majority. The Arab leaders, headed by Haj Amin al-Husseini, rejected the plan. Weizmann's

efforts to integrate Jews from Palestine in the war against Germany

resulted in the creation of the Jewish Brigade, which fought mainly in

the Italian front. After the war he grew embittered by the rise of

violence in Palestine and by the terrorist tendencies amongst followers

of the Revisionist fraction. His influence within the Zionist movement

decreased, yet he remained overwhelmingly influential outside of

Palestine (Eretz Israel). Weizmann lectured in chemistry at the University of Geneva between 1901 and 1903, and later taught at the University of Manchester. He became a British subject in 1910, and while a lecturer at Manchester he became famous for discovering how to use bacterial fermentation to produce large quantities of desired substances. He is considered to be the father of industrial fermentation. He used the bacterium Clostridium acetobutylicum (the Weizmann organism) to produce acetone. Acetone was used in the manufacture of cordite explosive propellants critical to the Allied war effort (Royal Navy Cordite Factory, Holton Heath).

Weizmann transferred the rights to the manufacture of acetone to the

Commercial Solvents Corporation in exchange for royalties. After the Shell Crisis of 1915 during World War I, he was director of the British Admiralty laboratories from 1916 until 1919. During World War II, he was an honorary adviser to the British Ministry of Supply and did research on synthetic rubber and high octane gasoline.

(Formerly Allied controlled sources of rubber were largely inaccessible

owing to Japanese occupation during World War II, giving rise to

heightened interest in such innovations). Concurrently,

Weizmann devoted himself to the establishment of a scientific institute

for basic research in the vicinity of his sprawling estate, in the town

of Rehovot. Weizmann saw great promise in science as a means to bring peace and prosperity to the area. As stated in his own words : "I

trust and feel sure in my heart that science will bring to this land

both peace and a renewal of its youth, creating here the springs of a

new spiritual and material life. [...] I speak of both science for its

own sake and science as a means to an end." His

efforts led in 1934 to the creation of the Daniel Sieff Research

Institute, which was financially supported by an endowment by the Baron Israel Sieff in memory of his late son. Weizmann actively conducted research in the laboratories of this institute, primarily in the field of organic chemistry. In 1949 the Sieff Institute was renamed the Weizmann Institute of Science in

his honor. Weizmann's success as a scientist and the success of the

Institute he founded make him an iconic figure in the heritage of the

Israeli scientific community today.

He met with United States President Harry Truman and worked to obtain the support of the United States for the establishment of the State of Israel. Weizmann became the first President of Israel in 1949.