<Back to Index>

- Meteorologist Luke Howard, 1772

- Poet and Painter William Blake, 1757

- King of Spain Alfonso XII, 1857

PAGE SPONSOR

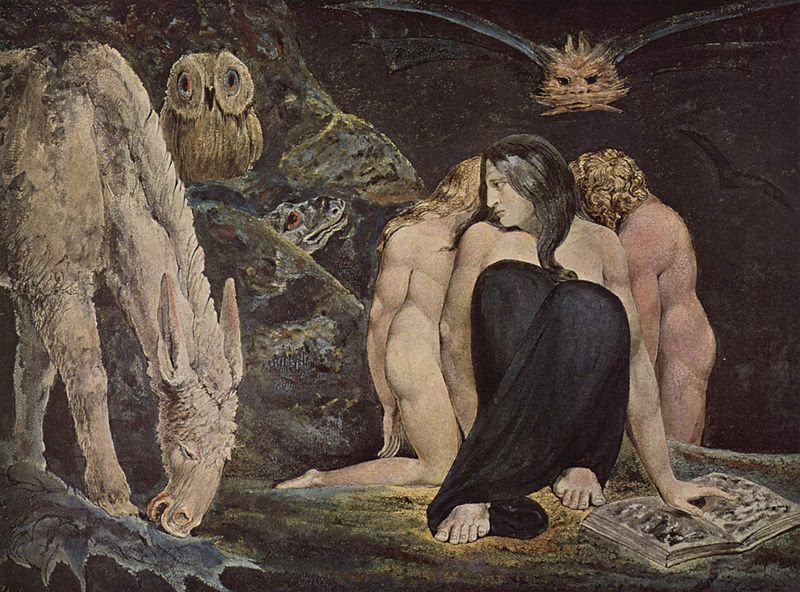

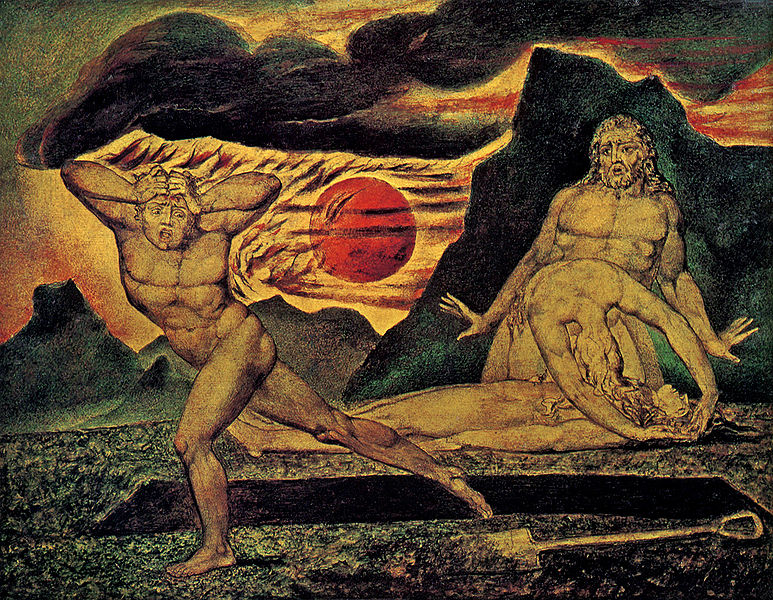

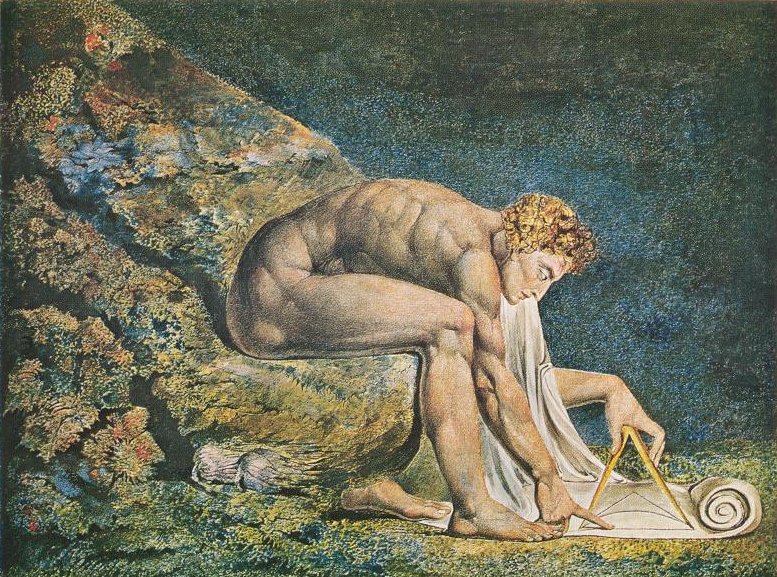

William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his lifetime, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of both the poetry and visual arts of the Romantic Age. His prophetic poetry has been said to form "what is in proportion to its merits the least read body of poetry in the English language". His visual artistry has led one contemporary art critic to proclaim him "far and away the greatest artist Britain has ever produced". Although he lived in London his entire life except for three years spent in Felpham, he produced a diverse and symbolically rich corpus, which embraced the imagination as "the body of God", or "Human existence itself".

Considered mad by contemporaries for his idiosyncratic views, Blake is held in high regard by later critics for his expressiveness and creativity, and for the philosophical and mystical undercurrents within his work. His paintings and poetry have been characterised as part of both the Romantic movement and "Pre-Romantic", for its large appearance in the 18th century. Reverent of the Bible but hostile to the Church of England, Blake was influenced by the ideals and ambitions of the French and American revolutions, as well as by such thinkers as Jakob Böhme and Emanuel Swedenborg. Despite these known influences, the singularity of Blake's work makes him difficult to classify. The 19th century scholar William Rossetti characterised Blake as a "glorious luminary," and as "a man not forestalled by predecessors, nor to be classed with contemporaries, nor to be replaced by known or readily surmisable successors." Historian Peter Marshall has classified Blake as one of the forerunners of modern anarchism, along with Blake's contemporary William Godwin.

William Blake was born on 28 November 1757 at 28 Broad Street (now Broadwick St) in the Soho district of London. He was the third of seven children, two of whom died in infancy. Blake's father, James, was a hosier. William did not attend school, and was educated at home by his mother Catherine Wright Armitage Blake. The Blakes were Dissenters, and are believed to have belonged to the Moravian Church. The Bible was an early and profound influence on Blake, and would remain a source of inspiration throughout his life. Blake

started engraving copies of drawings of Greek antiquities purchased for

him by his father, a practice that was then preferred to actual

drawing. Within these drawings Blake found his first exposure to

classical forms through the work of Raphael, Michelangelo, Marten Heemskerk and Albrecht Dürer.

His parents knew enough of his headstrong temperament that he was not

sent to school but was instead enrolled in drawing classes. He read

avidly on subjects of his own choosing. During this period, Blake was

also making explorations into poetry; his early work displays knowledge

of Ben Jonson and Edmund Spenser. On 4 August 1772, Blake became apprenticed to engraver James Basire of Great Queen Street, for the term of seven years. At

the end of this period, at the age of 21, he was to become a

professional engraver. No record survives of any serious disagreement

or conflict between the two during the period of Blake's

apprenticeship. However, Peter Ackroyd's

biography notes that Blake was later to add Basire's name to a list of

artistic adversaries — and then cross it out. This aside, Basire's

style of engraving was of a kind held to be old fashioned at the time, and

Blake's instruction in this outmoded form may have been detrimental to

his acquiring of work or recognition in later life. After two years,

Basire sent his apprentice to copy images from the Gothic churches in London (perhaps to settle a quarrel between Blake and James Parker, his fellow apprentice). His experiences in Westminster Abbey helped

form his artistic style and ideas. The Abbey of his day was decorated

with suits of armour, painted funeral effigies, and varicoloured

waxworks. Ackroyd notes that "... the most immediate [impression] would

have been of faded brightness and colour". In the long afternoons Blake spent sketching in the Abbey, he was occasionally interrupted by the boys of Westminster School,

one of whom "tormented" Blake so much one afternoon that he knocked the

boy off a scaffold to the ground, "upon which he fell with terrific

Violence". Blake beheld more visions in the Abbey, of a great procession of monks and priests, while he heard "the chant of plain song and chorale." On 8 October 1779, Blake became a student at the Royal Academy in Old Somerset House, near the Strand.

While the terms of his study required no payment, he was expected to

supply his own materials throughout the six year period. There, he

rebelled against what he regarded as the unfinished style of

fashionable painters such as Rubens, championed by the school's first president, Joshua Reynolds.

Over time, Blake came to detest Reynolds' attitude towards art,

especially his pursuit of "general truth" and "general beauty".

Reynolds wrote in his Discourses that

the "disposition to abstractions, to generalising and classification,

is the great glory of the human mind"; Blake responded, in marginalia

to his personal copy, that "To Generalize is to be an Idiot; To

Particularize is the Alone Distinction of Merit". Blake

also disliked Reynolds' apparent humility, which he held to be a form

of hypocrisy. Against Reynolds' fashionable oil painting, Blake

preferred the Classical precision of his early influences, Michelangelo and Raphael. David

Bindman suggests that Blake's antagonism towards Reynolds arose not so

much from the president's opinions (like Blake, Reynolds held history

painting to be of greater value than landscape and portraiture), but

rather "against his hypocrisy in not putting his ideals into practice." Certainly Blake was not averse to exhibiting at the Royal Academy, submitting works on six occasions between 1780 and 1808. Blake became friends with John Flaxman, Thomas Stothard and George Cumberland during his first year at the Royal Academy. They shared radical views, with Stothard and Cumberland joining the Society for Constitutional Information. Blake's first biographer, Alexander Gilchrist,

records that in June 1780 Blake was walking towards Basire's shop in

Great Queen Street when he was swept up by a rampaging mob that stormed Newgate Prison in London. They

attacked the prison gates with shovels and pickaxes, set the building

ablaze, and released the prisoners inside. Blake was reportedly in the

front rank of the mob during this attack. These riots, in response to a

parliamentary bill revoking sanctions against Roman Catholicism, later

came to be known as the Gordon Riots. They provoked a flurry of legislation from the government of George III, as well as the creation of the first police force. Despite

Gilchrist's insistence that Blake was "forced" to accompany the crowd,

some biographers have argued that he accompanied it impulsively, or

supported it as a revolutionary act. In contrast, Jerome McGann argues that the riots were reactionary, and that events would have provoked "disgust" in Blake. Blake met Catherine Boucher in

1782. At the time, Blake was recovering from a relationship that had

culminated in a refusal of his marriage proposal. He recounted the

story of his heartbreak for Catherine and her parents, after which he

asked Catherine, "Do you pity me?" When she responded affirmatively, he

declared, "Then I love you." Blake married Catherine – who was five

years his junior – on 18 August 1782 in St. Mary's Church, Battersea.

Illiterate, Catherine signed her wedding contract with an 'X'. The

original wedding certificate may still be viewed at the church, where a

commemorative stained glass window was installed between 1976 and 1982. Later,

in addition to teaching Catherine to read and write, Blake trained her

as an engraver. Throughout his life she would prove an invaluable aid

to him, helping to print his illuminated works and maintaining his spirits throughout numerous misfortunes. Blake's first collection of poems, Poetical Sketches, was printed around 1783. After

his father's death, William and former fellow apprentice James Parker

opened a print shop in 1784, and began working with radical publisher Joseph Johnson. Johnson's

house was a meeting place for some of the leading English intellectual

dissidents of the time: theologian and scientist Joseph Priestley, philosopher Richard Price, artist John Henry Fuseli, early feminist Mary Wollstonecraft and American revolutionary Thomas Paine. Along with William Wordsworth and William Godwin, Blake had great hopes for the French revolution and American revolutions and wore a Phrygian cap in solidarity with the French revolutionaries, but despaired with the rise of Robespierre and the Reign of Terror in France. In 1784 Blake also composed his unfinished manuscript An Island in the Moon. Blake illustrated Original Stories from Real Life (1788; 1791) by Mary Wollstonecraft.

They seem to have shared some views on sexual equality and the

institution of marriage, but there is no evidence proving without doubt

that they actually met. In 1793's Visions of the Daughters of Albion,

Blake condemned the cruel absurdity of enforced chastity and marriage

without love and defended the right of women to complete

self-fulfillment. In 1788, at the age of 31, Blake began to experiment with relief etching,

a method he would use to produce most of his books, paintings,

pamphlets and poems. The process is also referred to as illuminated

printing, and final products as illuminated books or prints.

Illuminated printing involved writing the text of the poems on copper

plates with pens and brushes, using an acid-resistant medium.

Illustrations could appear alongside words in the manner of earlier illuminated manuscripts.

He then etched the plates in acid to dissolve the untreated copper and

leave the design standing in relief (hence the name). This is a

reversal of the normal method of etching, where the lines of the design are exposed to the acid, and the plate printed by the intaglio method. Relief etching (which Blake also referred to as "stereotype" in The Ghost of Abel)

was intended as a means for producing his illuminated books more

quickly than via intaglio. Stereotype, a process invented in 1725,

consisted of making a metal cast from a wood engraving, but Blake’s

innovation was, as described above, very different. The pages printed

from these plates then had to be hand-coloured in water colours and

stitched together to make up a volume. Blake used illuminated printing

for most of his well known works, including Songs of Innocence and Experience, The Book of Thel, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, and Jerusalem. Although Blake has become most famous for his relief etching, his commercial work largely consisted of intaglio engraving,

the standard process of engraving in the eighteenth century in which

the artist would incise an image into the copper plate. This was a

complex and laborious process, with plates taking months or years to

complete, but as Blake's contemporary, John Boydell,

realised, such engraving offered a "missing link with commerce",

enabling artists to connect with a mass audience and so becoming an

immensely important activity by the end of the eighteenth century. Blake also employed intaglio engraving in his own work, most notably for the illustrations of the Book of Job,

completed just before his death. Most critical work has tended to

concentrate on Blake's relief etching as a technique because it is the

most innovative aspect of his art, but a 2009 study draws attention to

Blake's surviving plates, including those for the Book of Job: these

demonstrate that he made frequent use of a technique known as "repoussage", a means of obliterating mistakes by hammering them out by hitting the

back of the plate. Such techniques, typical of engraving work of the

time, are very different to the much faster and fluid way of drawing on

a plate that Blake employed for his relief etching, and indicates why

the engravings took so long to complete.

Blake's

marriage to Catherine remained a close and devoted one until his death.

Blake taught Catherine to write, and she helped him to colour his

printed poems. Gilchrist refers to "stormy times" in the early years of the marriage. Some biographers have suggested that Blake tried to bring a concubine into the marriage bed in accordance with the beliefs of the more radical branches of the Swedenborgian Society, but other scholars have dismissed these theories as conjecture. William and Catherine's first daughter and last child might be Thel described in The Book of Thel who was conceived as dead. In 1800, Blake moved to a cottage at Felpham in Sussex (now West Sussex) to take up a job illustrating the works of William Hayley, a minor poet. It was in this cottage that Blake began Milton: a Poem (the

title page is dated 1804 but Blake continued to work on it until 1808).

The preface to this work includes a poem beginning "And did those feet

in ancient time," which became the words for the anthem, "Jerusalem".

Over time, Blake came to resent his new patron, coming to believe that

Hayley was uninterested in true artistry, and preoccupied with "the

meer drudgery of business". Blake's disenchantment with Hayley

has been speculated to have influenced Milton: a Poem, in which Blake wrote that "Corporeal Friends are Spiritual Enemies." Blake's

trouble with authority came to a head in August 1803, when he was

involved in a physical altercation with a soldier called John Schofield. Blake

was charged not only with assault, but also with uttering seditious and

treasonable expressions against the King. Schofield claimed that Blake

had exclaimed, "Damn the king. The soldiers are all slaves." Blake would be cleared in the Chichester assizes of

the charges. According to a report in the Sussex county paper, "The

invented character of [the evidence] was ... so obvious that an

acquittal resulted." Schofield was later depicted wearing "mind forged manacles" in an illustration to Jerusalem. Blake returned to London in 1804 and began to write and illustrate Jerusalem (1804 – 1820), his most ambitious work. Having conceived the idea of portraying the characters in Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, Blake approached the dealer Robert Cromek,

with a view to marketing an engraving. Knowing that Blake was too

eccentric to produce a popular work, Cromek promptly commissioned

Blake's friend Thomas Stothard to execute the concept. When Blake

learned that he had been cheated, he broke off contact with Stothard. He also set up an independent exhibition in his brother's haberdashery shop at 27 Broad Street in the Soho district of London. The exhibition was designed to market his own version of the Canterbury illustration (titled The Canterbury Pilgrims), along with other works. As a result he wrote his Descriptive Catalogue (1809), which contains what Anthony Blunt has called a "brilliant analysis" of Chaucer. It is regularly anthologised as a classic of Chaucer criticism. It

also contained detailed explanations of his other paintings. The

exhibition itself, however, was very poorly attended, selling none of

the temperas or watercolours. Its only review, in The Examiner, was hostile. In 1818 he was introduced by George Cumberland's son to a young artist named John Linnell. Through Linnell he met Samuel Palmer, who belonged to a group of artists who called themselves the Shoreham Ancients.

This group shared Blake's rejection of modern trends and his belief in

a spiritual and artistic New Age. At the age of 65 Blake began work on illustrations for the Book of Job. These works were later admired by Ruskin, who compared Blake favourably to Rembrandt, and by Vaughan Williams, who based his ballet Job: A Masque for Dancing on a selection of the illustrations. Later

in his life Blake began to sell a great number of his works,

particularly his Bible illustrations, to Thomas Butts, a patron who saw

Blake more as a friend than a man whose work held artistic merit; this

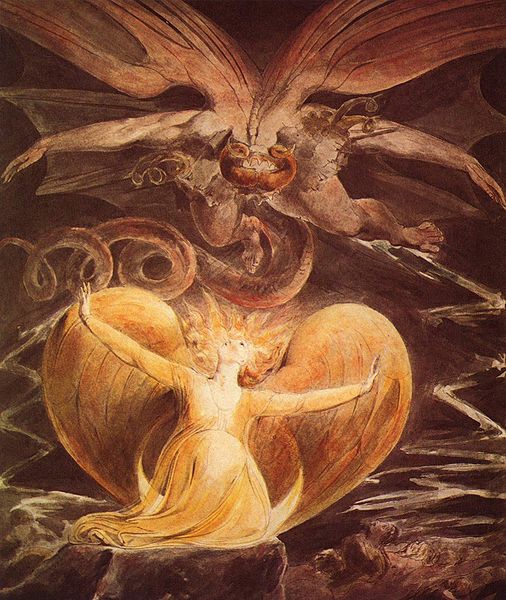

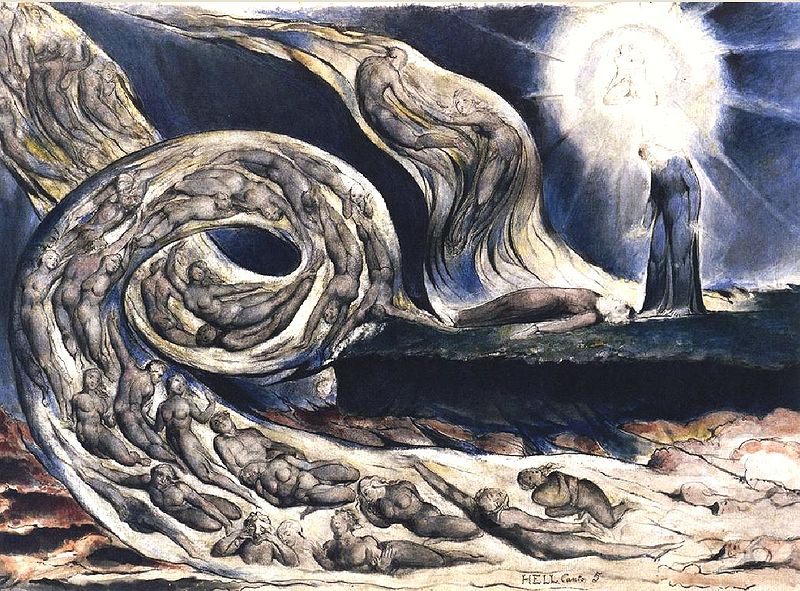

was typical of the opinions held of Blake throughout his life. The commission for Dante's Divine Comedy came to Blake in 1826 through Linnell,

with the ultimate aim of producing a series of engravings. Blake's

death in 1827 would cut short the enterprise, and only a handful of the

watercolours were completed, with only seven of the engravings arriving

at proof form. Even so, they have evoked praise: Blake's

illustrations of the poem are not merely accompanying works, but rather

seem to critically revise, or furnish commentary on, certain spiritual

or moral aspects of the text. Because

the project was never completed, Blake's intent may itself be obscured.

Some indicators, however, bolster the impression that Blake's

illustrations in their totality would themselves take issue with the

text they accompany: In the margin of Homer Bearing the Sword and His Companions,

Blake notes, "Every thing in Dantes Comedia shews That for Tyrannical

Purposes he has made This World the Foundation of All & the Goddess

Nature & not the Holy Ghost." Blake seems to dissent from Dante's

admiration of the poetic works of ancient Greece, and from the apparent glee with which Dante allots punishments in Hell (as evidenced by the grim humour of the cantos). At

the same time, Blake shared Dante's distrust of materialism and the

corruptive nature of power, and clearly relished the opportunity to

represent the atmosphere and imagery of Dante's work pictorially. Even

as he seemed to near death, Blake's central preoccupation was his

feverish work on the illustrations to Dante's Inferno; he is said to have spent one of the very last shillings he possessed on a pencil to continue sketching. On

the day of his death, Blake worked relentlessly on his Dante series.

Eventually, it is reported, he ceased working and turned to his wife,

who was in tears by his bedside. Beholding her, Blake is said to have

cried, "Stay Kate! Keep just as you are – I will draw your portrait –

for you have ever been an angel to me." Having completed this portrait

(now lost), Blake laid down his tools and began to sing hymns and

verses. At

six that evening, after promising his wife that he would be with her

always, Blake died. Gilchrist reports that a female lodger in the same

house, present at his expiration, said, "I have been at the death, not

of a man, but of a blessed angel." George Richmond gives the following account of Blake's death in a letter to Samuel Palmer: Catherine

paid for Blake's funeral with money lent to her by Linnell. He was

buried five days after his death – on the eve of his forty-fifth wedding anniversary – at the Dissenter's burial ground in Bunhill Fields, where his parents were also interred. Present at the ceremonies were Catherine, Edward Calvert, George Richmond, Frederick Tatham and

John Linnell. Following Blake's death, Catherine moved into Tatham's

house as a housekeeper. During this period, she believed she was

regularly visited by Blake's spirit. She continued selling his

illuminated works and paintings, but would entertain no business

transaction without first "consulting Mr. Blake". On

the day of her own death, in October 1831, she was as calm and cheerful

as her husband, and called out to him "as if he were only in the next

room, to say she was coming to him, and it would not be long now". On her death, Blake's manuscripts were inherited by Frederick Tatham, who burned several he deemed heretical or politically radical. Tatham was an Irvingite, one of the many fundamentalist movements of the 19th century, and was severely opposed to any work that smacked of blasphemy. Also, John Linnell erased sexual imagery from a number of Blake's drawings. Since

1965, the exact location of William Blake's grave had been lost and

forgotten, while gravestones were taken away to create a new lawn.

Nowadays, Blake’s grave is commemorated by a stone that reads "Near by

lie the remains of the poet-painter William Blake 1757 - 1827 and his

wife Catherine Sophia 1762 - 1831". This memorial stone is situated

approximately 20 metres away from the actual spot of Blake’s

grave, which is not marked. However, members of the group Friends of

William Blake have rediscovered the location of Blake's grave and

intend to place a permanent memorial at the site. Blake is now recognised as a saint in the Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica. The Blake Prize for Religious Art was

established in his honour in Australia in 1949. In 1957 a memorial was

erected in Westminster Abbey, in memory of him and his wife.

“ He

died ... in a most glorious manner. He said He was going to that

Country he had all His life wished to see & expressed Himself

Happy, hoping for Salvation through Jesus Christ — Just before he died His Countenance became fair. His eyes Brighten'd and he burst out Singing of the things he saw in Heaven. ”