<Back to Index>

- Chemist Henry Louis Le Chatelier, 1850

- Painter Max Slevogt, 1868

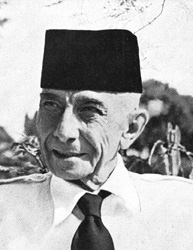

- Indonesian Freedom Fighter Ernest François Eugène Douwes Dekker, 1879

PAGE SPONSOR

Ernest François Eugène Douwes Dekker (8 October 1879 in Pasuruan, East Java, – 28 August 1950 in Bandung, West Java) was an Indonesian freedom fighter and politician of Indo descent. He was related to the famous Dutch writer, Multatuli, whose real name was Eduard Douwes Dekker. In his youth, he took part in the Second Boer War in South Africa on the Boer side.

His thoughts were highly influential in early years of the Indonesian

freedom movement. After Indonesian independence, he adopted the Javanese name, Danoedirdja Setiaboeddhi. Douwes Dekker was born in Pasuruan, in the north eastern city of Java, 80 km south of Surabaya. His father was Auguste Henri Edouard Douwes Dekker, a broker and bank agent, of a Dutch family living in the then-Dutch East Indies. His mother was Louisa Margaretha Neumann, of half-German and half-Javanese descent; the younger Douwes Dekker was related to the famous writer, Eduard Douwes Dekker, author of Max Havelaar, who was his grandfather's brother. After studying in Lower School in Pasuruan, he moved to Surabaya, and later to Batavia. In 1897, he gained his diploma and worked on a coffee plantation in Malang, East Java. Later he moved to a sugar plantation in Kraksaan, East Java. During his years in these plantations, he came in contact with ordinary Javanese and saw the realities of their hard work. In 1900, along with his brothers Julius and Guido, he decided to volunteer for service in the Second Boer War. They arrived in Transvaal, and became citizens of that state. He based his actions on the belief that the Boers were victims of British expansionism, and as fellow descendant of the Dutch, he was obliged to help. In the

course of the war, he was captured by the British and placed in an

internment camp on Ceylon. Douwes Dekker was later released and returned to the Dutch East Indies and Paris in 1903. In the Dutch East Indies, Douwes Dekker, then still in his twenties, started a career as a journalist, first in Semarang and later in Batavia. There he worked with Indo activist Karel Zaalberg,

the chief editor of the newspaper, whom he befriended. On 5 May 1903 he

married Clara Charlotte Deije, who would bear him three children.

Unlike other people of European descent, he did not favour colonialism, strongly advocating self-management, and finally the independence, of

the Dutch East Indies. This was prompted partly by his experience in

watching the lives of plantation workers and partly by discrimination

he had suffered, through being only considered half-Dutch and a

second-class citizen. During these times, he published many articles advocating independence, and "Indies nationalism". In

1913, close associates of Douwes Dekker, including physicians Tjipto

Mangunkusumo and Suwardi Surjaningrat, established the Native Committee

in Bandung, which later became Indische Partij. This

was considered a breakthrough, because most organisations had never so

openly advocated independence. In March 1913, the party claimed

approximately 7000 members, approximately 5500 of whom were Indos (people

of mixed Dutch-Indonesian ancestry) along with 1500 native Indonesians.

The Colonial government quickly became worried and the party was

forbidden. This led to the exile to the Netherlands of

Douwes Dekker and his two Javanese associates. In exile, they worked

with liberal Dutchmen and compatriot students. It is believed that the

term Indonesia was

first used in the name of an organization, the Indonesian Alliance of

Students, with which they were associated during the early 1920s. Later

he was allowed to return to the East Indies. In 1922, he taught in

Bandung in a lower school. Two years later as head of the school, he

renamed it the "Ksatrian Institute". This institute was officially

recognised by the government in 1926. In the same year, he married

Johanna Mussel, one of its teachers, six years after divorcing his

first wife. Later, however, his activities were branded illegal, and in 1936 he was condemned to three months in prison. He was still actively advocating independence and sharing his thoughts with other intellectuals, among them Sukarno, who considered Douwes Dekker as his teacher. Later,

however, his influence was overshadowed by the politics of his student

Sukarno's Indonesian National Party (PNI), Islamist Sarekat Islam, and Communist Party of Indonesia. During World War II, Dutch authorities, who considered him a dangerous activist, exiled him, along with many Indo-Europeans of German descent, to Suriname. He would spend years in a forest prison camp called "Joden Savanne". Douwes Dekker returned to Indonesia on 2 January 1947. After he returned to Indonesia, he was appointed a member of the provisional parliament, or Komite Nasional Indonesia Pusat (Indonesian National Central Committee).

In February 1947, he changed his name to "Danudirja Setiabudi" which

means 'powerful substance, faithful spirit'. In 8 March 1947 after

divorcing his second wife, he married Haroemi Wanasita, in an Islamic

ceremony. He spent his later years in Bandung, writing his autobiography, 70 Jaar Konsekwent (1950). Douwes Dekker died in 1950. His legacy is still appreciated in Indonesia; a district and a main street in Jakarta are named Setiabudi in his honour. In Bandung, there is also a main street called Setiabudi, and another is named Ksatrian after his school. He was recognized as National Hero by President Sukarno. His life is recorded in a biography, 'Het Leven van EFE Douwes Dekker, by Frans Glissenaar in 1999.