<Back to Index>

- Surgeon William Cheselden, 1688

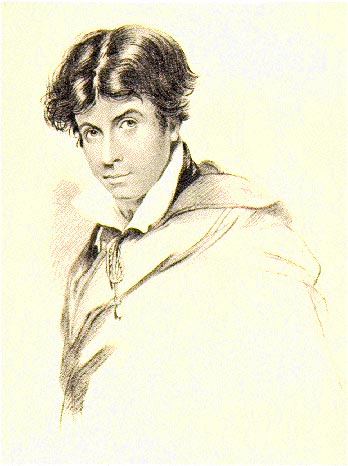

- Writer James Henry Leigh Hunt, 1784

- Dictator of Nigeria Yakubu "Jack" Dan-Yumma Gowon, 1934

PAGE SPONSOR

James Henry Leigh Hunt (19 October 1784 – 28 August 1859) was an English critic, essayist, poet and writer.

Leigh Hunt was born at Southgate, London, where his parents had settled after leaving the USA. His father, a lawyer from Philadelphia, and his mother, a merchant's daughter and a devout Quaker, had been forced to come to Britain because of their loyalist sympathies during the American War of Independence. Hunt's father took holy orders, and became a popular preacher, but was unsuccessful in obtaining a permanent living. Hunt's father was then employed by James Brydges, 3rd Duke of Chandos, as tutor to his nephew, James Henry Leigh, after whom Leigh Hunt was named.

Leigh Hunt was educated at Christ's Hospital from 1791 to 1799, a period which is detailed in his autobiography. He entered the school shortly after Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Charles Lamb had both left, however Thomas Barnes was a schoolfriend of his. One of the current boarding houses at Christ's Hospital is named after him. As a boy, he was an ardent admirer of Thomas Gray and William Collins, writing many verses in imitation of them. A speech impediment, later cured, prevented his going to university. "For some time after I left school," he says, "I did nothing but visit my school fellows, haunt the book-stalls and write verses." His poems were published in 1801 under the title of Juvenilia, and introduced him into literary and theatrical society. He began to write for the newspapers, and published in 1807 a volume of theatre criticism, and a series of Classic Tales with critical essays on the authors. Hunt's early essays were published by Edward Quin, editor and owner of The Traveller.

In 1808 he left the War Office, where he had been working as a clerk, to become editor of the Examiner, a newspaper founded by his brother, John. This journal soon acquired a reputation for unusual political independence; it would attack any worthy target, "from a principle of taste," as John Keats expressed it. In 1813, an attack on the Prince Regent, based on substantial truth, resulted in prosecution and a sentence of two years' imprisonment for each of the brothers — Leigh Hunt served his term at the Surrey County Gaol. Leigh Hunt's visitors in prison included Lord Byron, John Moore, Lord Brougham, Charles Lamb and others, whose acquaintance influenced his later career. The stoicism with which Leigh Hunt bore his imprisonment attracted general attention and sympathy.

In 1810 - 1811 he edited a quarterly magazine, the Reflector, for his brother John. He wrote "The Feast of the Poets" for this, a satire, which offended many contemporary poets, particularly William Gifford of the Quarterly. The essays afterwards published under the title of the Round Table (2 volumes, 1816 – 1817), jointly with William Hazlitt, appeared in the Examiner. In 1816 he made a mark in English literature with the publication of Story of Rimini. Hunt's preference was decidedly for Chaucer's verse style, as adapted to the Modern English by John Dryden, in opposition to the epigrammatic couplet of Alexander Pope which

had superseded it. The poem is an optimistic narrative which runs

contrary to the tragic nature of its subject. Hunt's flippancy and

familiarity, often degenerating into the ludicrous, subsequently made

him a target for ridicule and parody. In 1818 appeared a collection of poems entitled Foliage, followed in 1819 by Hero and Leander, and Bacchies and Ariadne. In the same year he reprinted these two works with The Story of Rimini and The Descent of Liberty with the title of Poetical Works, and started the Indicator, in which some of his best work appeared. Both Keats and Shelley belonged to the circle gathered around him at Hampstead, which also included William Hazlitt, Charles Lamb, Bryan Procter, Benjamin Haydon, Charles Cowden Clarke, C.W. Dilke, Walter Coulson and John Hamilton Reynolds. He had for some years been married to Marianne Kent.

His own affairs were in confusion, and only Shelley's generosity saved

him from ruin. In return he showed sympathy to Shelley during the

latter's domestic distresses, and defended him in the Examiner. He introduced Keats to Shelley and wrote a very generous appreciation of him in the Indicator. Keats seems, however, to have subsequently felt that Hunt's example as a poet had been in some respects detrimental to him. After

Shelley's departure for Italy in 1818, Leigh Hunt became even poorer,

and the prospects of political reform less satisfactory. Both his

health and his wife's failed, and he was obliged to discontinue the Indicator (1819 – 1821),

having, he says, "almost died over the last numbers." Shelley suggested

that Hunt go to Italy with him and Byron to establish a quarterly

magazine in which Liberal opinions

could be advocated with more freedom than was possible at home. An

injudicious suggestion, it would have done little for Hunt or the

Liberal cause at the best, and depended entirely upon the co-operation

of the capricious, parsimonious Byron. Byron's principal motive for

agreeing appears to have been the expectation of acquiring influence

over the Examiner,

and he was mortified to discover that Hunt was no longer interested in

the "Examiner". Leigh Hunt left England for Italy in November 1821, but

storm, sickness and misadventure retarded his arrival until 1 July

1822, a rate of progress which Thomas Love Peacock appropriately compares to the navigation of Ulysses. The death of Shelley, a few weeks later, destroyed every prospect of success for the Liberal.

Hunt was now virtually dependent upon Byron, who did not relish the

idea of being patron to Hunt's large and troublesome family. Byron's

friends also scorned Hunt. The Liberal lived through four quarterly numbers, containing contributions no less memorable than Byron's "Vision of Judgment" and Shelley's translations from Faust; but in 1823 Byron sailed for Greece, leaving Hunt at Genoa to

shift for himself. The Italian climate and manners, however, were

entirely to Hunt's taste, and he protracted his residence until 1825,

producing in the interim Ultra - Crepidarius: a Satire on William Gifford (1823), and his matchless translation (1825) of Francesco Redi's Bacco in Toscana. In 1825 a litigation with his brother brought him back to England, and in 1828 he published Lord Byron and some of his Contemporaries, a corrective to idealized portraits of Byron. The public was shocked

that Hunt, who had been obliged to Byron for so much, would "bite the

hand that fed him" in this way. Hunt especially writhed under the

withering satire of Moore. For many years afterwards, the history of

Hunt's life is a painful struggle with poverty and sickness. He worked

unremittingly, but one effort failed after another. Two journalistic

ventures, the Tatler (1830 – 1832), a daily devoted to literary and dramatic criticism, and Leigh Hunt's London Journal (1834 – 1835),

were discontinued for want of subscribers, although the latter

contained some of his best writing. His editorship (1837 – 1838) of the Monthly Repository, in which he succeeded William Johnson Fox, was also unsuccessful. The adventitious circumstances which allowed the Examiner to succeed no longer existed, and Hunt's personality was unsuited to the general body of readers. In

1832 a collected edition of his poems was published by subscription,

the list of subscribers including many of his opponents. In the same year was printed for private circulation Christianism, the work afterwards published (1853) as The Religion of the Heart. A copy sent to Thomas Carlyle secured his friendship, and Hunt went to live next door to him in Cheyne Row in 1833. Sir Ralph Esher, a romance of Charles II's period, had a success, and Captain Sword and Captain Pen (1835),

a spirited contrast between the victories of peace and the victories of

war, deserves to be ranked among his best poems. In 1840 his

circumstances were improved by the successful representation at Covent

Garden of his play Legend of Florence. Lover's Amazements, a comedy, was acted several years afterwards, and was printed in Leigh Hunt's Journal (1850 – 1851); other plays remained in manuscript. In 1840 he wrote introductory notices to the work of Sheridan and to Edward Moxon's edition of the works of William Wycherley, William Congreve, John Vanbrugh and George Farquhar, a work which furnished the occasion of Macaulay's essay on the Dramatists of the Restoration. The narrative poem The Palfrey was published in 1842. The

time of Hunt's greatest difficulties was between 1834 and 1840. He was

at times in absolute poverty, and his distress was aggravated by

domestic complications. By Macaulay's recommendation he began to write

for the Edinburgh Review. In 1844 Mary Shelley and her son, on succeeding to the family estates, settled an annuity of £120 upon Hunt; and in 1847 Lord John Russell procured him a pension of £200. Now living in improved comfort, Hunt published the companion books, Imagination and Fancy (1844), and Wit and Humour (1846),

two volumes of selections from the English poets, which displayed his

refined, discriminating critical tastes. His book on the pastoral

poetry of Sicily, A Jar of Honey from Mount Hybla (1848), is also delightful. The Town (2 vols., 1848) and Men, Women and Books (2 vols., 1847) are partly made up from former material. The Old Court Suburb (2 vols., 1855) is a sketch of Kensington, where he long resided. In 1850 he published his Autobiography (3 vols.), a naive and affected, but accurate, piece of self portraiture. A Book for a Corner (2 vols.) was published in 1849, and his Table Talk appeared in 1851. In 1855 his narrative poems, original and translated, were collected under the title Stories in Verse. He died in Putney on the 28 August 1859, and is buried at Kensal Green Cemetery. In September 1966 Christ's Hospital named one of its Houses in memory of him. Leigh Hunt was the original of Harold Skimpole in Bleak House.

"Dickens wrote in a letter of 25 September 1853, 'I suppose he is the

most exact portrait that was ever painted in words! ... It is an

absolute reproduction of a real man'; and a contemporary critic

commented, 'I recognized Skimpole instantaneously; ... and so did every

person whom I talked with about it who had ever had Leigh Hunt's acquaintance.'" G.K. Chesterton suggested

that Dickens "may never once have had the unfriendly thought, 'Suppose

Hunt behaved like a rascal!'; he may have only had the fanciful

thought, 'Suppose a rascal behaved like Hunt!'".