<Back to Index>

- Journalist Klas Pontus Arnoldson, 1844

- Painter Mary Moser, 1744

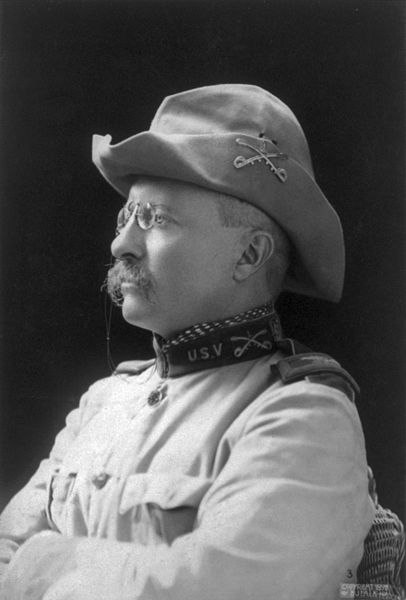

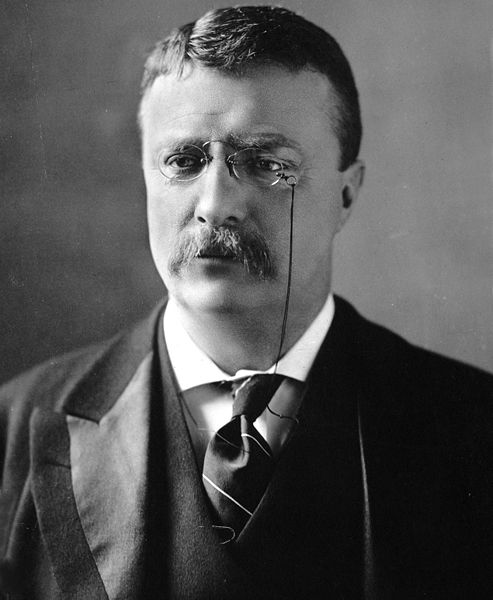

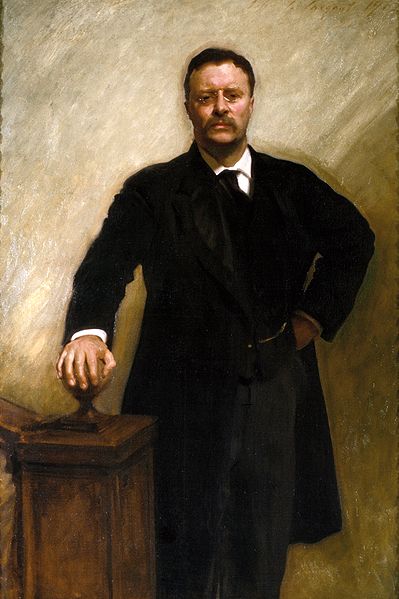

- 26th President of the United States Theodore "Teddy" Roosevelt, 1858

PAGE SPONSOR

Theodore "Teddy" Roosevelt (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919) was the 26th President of the United States. He is noted for his energetic personality, range of interests and achievements, leadership of the Progressive Movement, and his "cowboy" image and robust masculinity. He was a leader of the Republican Party and founder of the short lived Progressive ("Bull Moose") Party of 1912. Before becoming President (1901 – 1909) he held offices at the municipal, state, and federal level of government. Roosevelt's achievements as a naturalist, explorer, hunter, author, and soldier are as much a part of his fame as any office he held as a politician.

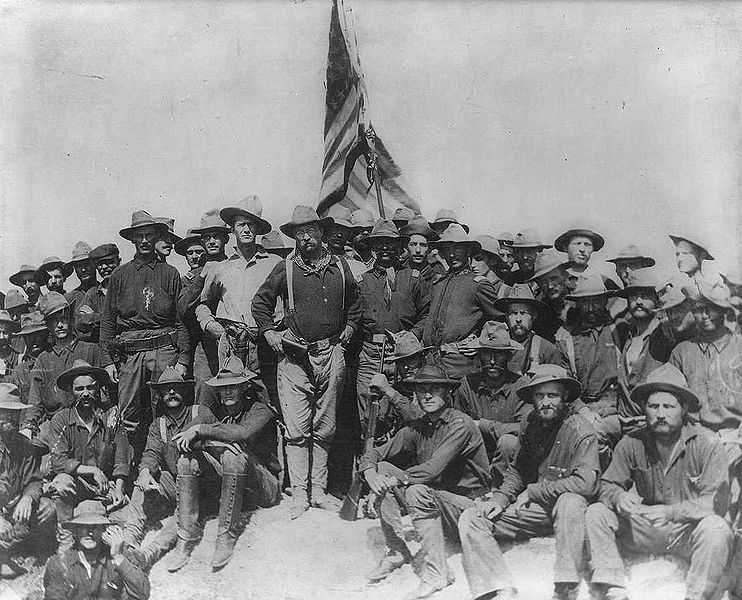

Born to a wealthy family, Roosevelt was an unhealthy child suffering from asthma who stayed at home studying natural history. In response to his physical weakness, he embraced a strenuous life. He was home schooled and became a passionate student of nature. He attended Harvard, where he boxed and developed an interest in naval affairs. In 1881, one year out of Harvard, he was elected to the state legislature as its youngest member. Roosevelt's first historical book, The Naval War of 1812, published in 1882, established his professional reputation as a serious historian. After a few years of living in the Badlands, Roosevelt returned to New York City, where he gained fame for fighting police corruption. While effectively running the Department of the Navy, Spanish American War broke out from which he resigned and led a small regiment in Cuba known as the Rough Riders, earning himself a nomination for the Medal of Honor (which was received posthumously on his behalf on January 16, 2001). After the war, he returned to New York and was elected governor in a close fought election. Within two years later he was elected Vice President of the United States. In 1901, President William McKinley was assassinated, and Roosevelt became president at the age of 42, taking office at the youngest age of any U.S. President in history. Roosevelt attempted to move the Republican Party in the direction of Progressivism, including trust busting and increased regulation of businesses. Roosevelt coined the phrase "Square Deal" to describe his domestic agenda, emphasizing that the average citizen would get a fair shake under his policies. As an outdoorsman and naturalist, he promoted the conservation movement. On the world stage, Roosevelt's policies were characterized by his slogan, "Speak softly and carry a big stick". Roosevelt was the force behind the completion of the Panama Canal; he sent out the Great White Fleet to display American power, and he negotiated an end to the Russo - Japanese War, for which he won the Nobel Peace Prize. Roosevelt was the first American to win the Nobel Prize in any field. Roosevelt declined to run for re-election in 1908. After leaving office, he embarked on a safari to Africa and a tour of Europe. On his return to the US, a bitter rift developed between Roosevelt and his anointed successor as President, William Howard Taft. Roosevelt attempted in 1912 to wrest the Republican nomination from Taft, and when he failed, he launched the Bull Moose Party. In the election, Roosevelt became the only third party candidate to come in second place, beating Taft but losing to Woodrow Wilson. After the election, Roosevelt embarked on a major expedition to South America; the river on which he traveled now bears his name. He contracted malaria on the trip, which damaged his health, and he died a few years later, at the age of 60. Roosevelt has consistently been ranked by scholars as one of the greatest U.S. Presidents.

The

Roosevelt family, immigrants of Dutch origin, had been in New York

since the mid 17th century. Roosevelt was born into a considerable

wealth, for the family, by the 19th century, had grown in wealth, power

and influence from the profits of several businesses including hardware

and plate-glass importing. The family was strongly Democratic in its political affiliation until the mid 1850s, then joined the new Republican Party. Theodore's father, known in the family as "Thee", was a New York City philanthropist,

merchant, and partner in the family glass importing firm Roosevelt and

Son. "Father," as the children called him, was an ardent Unionist, a prominent supporter of Abraham Lincoln and the Union effort during the American Civil War. His mother Martha "Mittie" Bulloch was a Southern belle from a slave owning family in Roswell, Georgia, and maintained Confederate sympathies. Mittie's brother, Theodore's uncle, James Dunwoody Bulloch, was a United States Navy officer who became a Confederate admiral and naval procurement officer and secret agent in Britain. Another uncle, Irvine Bulloch, was a midshipman on the Confederate raider CSS Alabama; both remained in England after the war. From his grandparents' home, the young Roosevelt witnessed Abraham Lincoln's funeral procession when it came through New York. Theodore Roosevelt was born on October 27, 1858, in a four-story brownstone at 28 East 20th Street, in the modern day Gramercy section of New York City, the second of four children of Theodore Roosevelt, Sr. (1831 – 1878) and Martha "Mittie" Bulloch (1835 – 1884). He had an elder sister Anna, nicknamed "Bamie" as a child and "Bye" as an adult for being always on the go, and two younger siblings — his brother Elliott (the father of future First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt), and his sister Corinne (grandmother of newspaper columnists Joseph and Stewart Alsop). Sickly and asthmatic as

a child, Roosevelt had to sleep propped up in bed or slouching in a

chair during much of his early childhood, and had frequent ailments.

Despite his illnesses, he was a hyperactive and often mischievous

child, who suffered severely from tone deafness. His lifelong interest in zoology was formed at age seven upon seeing a dead seal at

a local market. After obtaining the seal's head, the young Roosevelt

and two of his cousins formed what they called the "Roosevelt Museum of

Natural History". Learning the rudiments of taxidermy,

he filled his makeshift museum with many animals that he killed or

caught, studied, and prepared for display. At age nine, he codified his

observation of insects with a paper titled "The Natural History of

Insects". Roosevelt described his childhood experiences in a 1903 letter, writing: As

far as I can remember they were absolutely commonplace. I was a rather

sickly, rather timid little boy, very fond of desultory reading and of

natural history, and not excelling in any form of sport. Owing to my

asthma I was not able to go to school, and I was nervous and

self-conscious, so that as far as I can remember my belief is that I

was rather below than above my average playmate in point of leadership;

though as I had an imaginative temperament this sometimes made up for

my other short-comings. Altogether, while, thanks to my father and

mother, I had a very happy childhood I am inclined to look back at it

with some wonder that I should have come out of it as well as I have!

It was not until after I was sixteen that I began to show any prowess,

or even ordinary capacity; up to that time, except making collections

of natural history, reading a good deal in certain narrowly limited

fields and indulging in the usual scribbling of the small boy who does

not excel in sport, I cannot remember that I did anything that even

lifted me up to the average. To combat his poor physical condition, his father encouraged the young Roosevelt to take up exercise. Roosevelt started boxing lessons. Two trips abroad had a permanent impact: family tours of Europe in 1869 and 1870, and of the Middle East 1872 to 1873. Theodore,

Sr. had a tremendous influence on his son, of whom Roosevelt wrote, "My

father, Theodore Roosevelt, was the best man I ever knew. He combined

strength and courage with gentleness, tenderness, and great

unselfishness. He would not tolerate in us children selfishness or

cruelty, idleness, cowardice, or untruthfulness." He

told his sister Corinne that he never took any serious step or made any

vital decision for his country without thinking first what position his

father would have taken. Alice Hathaway Lee (July 29, 1861 in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts – February 14, 1884 in Manhattan, New York) was the first wife of Theodore Roosevelt and mother of their child, Alice. Roosevelt's wife, Alice, died of an undiagnosed (since it was camouflaged by her pregnancy) case of kidney failure (in those days called Bright's disease) two days after Alice Lee was born. Theodore Roosevelt's mother had died of typhoid fever in

the same house, on the same day, at 3 am, on St. Valentine's Day, some

eleven hours earlier. After the near simultaneous deaths of his mother

and wife, Roosevelt left his daughter in the care of his sister, Anna

"Bamie/Bye" in New York City. In his diary he wrote a large X on the

page and wrote "the light has gone out of my life." A short time later,

Roosevelt wrote a tribute to his wife published privately indicating

that: She

was beautiful in face and form, and lovelier still in spirit; As a

flower she grew, and as a fair young flower she died. Her life had been

always in the sunshine; there had never come to her a single sorrow;

and none ever knew her who did not love and revere her for the bright,

sunny temper and her saintly unselfishness. Fair, pure, and joyous as a

maiden; loving, tender, and happy. As a young wife; when she had just

become a mother, when her life seemed to be just begun, and when the

years seemed so bright before her — then, by a strange and terrible fate,

death came to her. And when my heart’s dearest died, the light went

from my life forever. To the immense disappointment of his daughter, Alice,

he would not speak of his wife publicly or privately for the rest of

his life and did not mention her in his autobiography. As late as 1919,

while working with Joseph Bucklin Bishop on a biography which included

a collection of his letters, Roosevelt would mention neither his first

marriage nor the circumstances of his second marriage, which took place in London. A letter written then to a young female friend of Roosevelt's sister Corinne,

who had lost a loved one, demonstrated Roosevelt's method of dealing

with catastrophic loss. After his death, in her memoirs, his sister

Corinne described this letter as "full of a certain quality — what

perhaps I might call a righteous ruthlessness specially characteristic

of Theodore Roosevelt," because he had written, "I hate to think of her

suffering; but the only thing for her to do now is to treat it as past,

the event as finished and out of her life; to dwell on it, and above

all to keep talking of it with any one, would be both weak and morbid.

She should try not to think of it; this she cannot wholly avoid, but

she CAN avoid speaking of it. She should show a brave and cheerful

front to the world, whatever she feels; and henceforth she should never

speak one word of the matter to any one. In the long future, when the

memory is too dead to throb, she may, if she wishes, speak of it once

more, but if wise and brave, she will not speak of it now." Roosevelt

would later indicate that this was his only method of dealing with a

such a debilitating loss, indicating to a grieving friend, "There is

nothing more foolish and cowardly than to be beaten down by a sorrow

which nothing we can do will change." or, in the words of his biographer, Edmund Morris,

"Like a lion obsessively trying to drag a spear from its flank,

Roosevelt set about dislodging Alice Lee from his soul. Nostalgia, a

weakness to which he was abnormally vulnerable, could be indulged if it

was pleasant, but if painful it must be suppressed, 'until the memory

is too dead to throb.'" Young

"Teedie", as he was nicknamed as a child (the nickname "Teddy" was from

his first wife, Alice Hathaway Lee, and he later harbored an intense

dislike for it due to her untimely death), was mostly home schooled by

tutors and his parents. A leading biographer says: "The most obvious

drawback to the home schooling Roosevelt received was uneven coverage

of the various areas of human knowledge." He

was solid in geography (thanks to his careful observations on all his

travels) and very well read in history, strong in biology, French, and German, but deficient in mathematics, Latin and Greek. He matriculated at Harvard College in

1876. His father's death in 1878 was a tremendous blow, but Roosevelt

redoubled his activities. He did well in science, philosophy and

rhetoric courses but fared poorly in Latin and Greek. He studied

biology with great interest and indeed was already an accomplished naturalist and published ornithologist. He had a photographic memory and developed a life-long habit of devouring books, memorizing every detail. He

was an eloquent conversationalist who, throughout his life, sought out

the company of the smartest people. He could multitask in extraordinary

fashion, dictating letters to one secretary and memoranda to another,

while browsing through a new book. As a young Sunday school teacher at Christ Church,

Roosevelt was once reprimanded for rewarding a young man $1 who showed

up to his class with a black eye for fighting a bully. The bully had

supposedly pinched his sister and the young man was standing up for

her. Roosevelt thought this to be honorable; however, the church deemed

it too flagrant of support of fighting. While at Harvard, Roosevelt was active in rowing, boxing, the Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity, and was a member of the Porcellian Club. He also edited a student magazine. He was runner-up in the Harvard boxing championship, losing to C.S. Hanks. In

later years, pondering his largely home-based early education and his

college experience in his autobiography, Roosevelt expressed mixed

feelings about its value in preparing him for public service, writing: All

this individual morality I was taught by the books I read at home and

the books I studied at Harvard. But there was almost no teaching of the

need for collective action, and of the fact that in addition to, not as

a substitute for, individual responsibility, there is a collective

responsibility.... The teaching which I received was genuinely

democratic in one way. It was not so democratic in another. I grew into

manhood thoroughly imbued with the feeling that a man must be respected

for what he made of himself. But I had also, consciously or

unconsciously, been taught that socially and industrially pretty much

the whole duty of the man lay in thus making the best of himself; that

he should be honest in his dealings with others and charitable in the

old-fashioned way to the unfortunate; but that it was no part of his

business to join with others in trying to make things better for the

many by curbing the abnormal and excessive development of individualism

in a few. Now I do not mean that this training was by any means all

bad. On the contrary, the insistence upon individual responsibility

was, and is, and always will be, a prime necessity.... But such

teaching, if not corrected by other teaching, means acquiescence in a

riot of lawless business individualism which would be quite as

destructive to real civilization as the lawless military individualism

of the Dark Ages. I left college and entered the big world owing more

than I can express to the training I had received, especially in my own

home; but with much else also to learn if I were to become really

fitted to do my part in the work that lay ahead for the generation of

Americans to which I belonged. Upon

graduating, Roosevelt underwent a physical examination and his doctor

advised him that due to serious heart problems, he should find a desk

job and avoid strenuous activity. He chose to embrace strenuous life

instead. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa (22nd of 177) from Harvard in 1880, and entered Columbia Law School. When offered a chance to run for New York Assemblyman in 1881, he dropped out of law school to pursue his new goal of entering public life. Roosevelt

would have graduated from Columbia in 1882, as the law school

curriculum was covered in two years at that time; he received a

posthumous law degree from Columbia in 2008. While at Harvard, Roosevelt began a systematic study of the role played by the nascent US Navy in the War of 1812, largely completing two chapters of a book he would publish after graduation. He would later recall that in the middle of mathematics classes at Harvard, his mind would wander from his lessons to the accomplishments of the infant US Navy. Reading

through literature on the subject, Roosevelt found both American and

British accounts heavily biased and that there had been no systematic

study of the tactics employed in the war. Although a challenge for a

young man with no formal military or naval education, but helped in

part by his two former Confederate naval officer Bulloch uncles, he did

his own research using original source materials and official US Navy

records. Unlike previous American and British books that ignored

quantifiable facts to push a specific agenda, Roosevelt's carefully

researched book was akin to today's modern doctoral dissertations,

complete with carefully researched drawings depicting individual and

combined ship maneuvers, charts depicting the differences in iron throw

weights of cannon shot between American and British forces, and

analyses of the differences between British and American leadership

down to the ship-to-ship level. It is today considered one of the first

modern American historical works. Published after Roosevelt's

graduation from Harvard, The Naval War of 1812 was immediately accepted by reviewers who praised the book’s scholarship and style. The newly established Naval War College adopted

it for study, and the Department of the Navy ordered a copy placed in

the libraries of every capital ship in the fleet. This book would help

establish Roosevelt's reputation as a serious historian. Roosevelt

brought out a subsequent edition including questions and answers from

both scholars and critics. One modern naval historian wrote:

"Roosevelt’s study of the War of 1812 influenced all subsequent

scholarship on the naval aspects of the War of 1812 and continues to be

reprinted. More than a classic, it remains, after 120 years, a standard

study of the war."

Roosevelt was a Republican activist

during his years in the Assembly, writing more bills than any other New

York state legislator. Already a major player in state politics, he

attended the Republican National Convention in 1884 and fought alongside the Mugwump reformers; they lost to the Stalwart faction that nominated James G. Blaine. Refusing to join other Mugwumps in supporting Democrat Grover Cleveland, the Democratic nominee, he debated with his friend Henry Cabot Lodge the

pros and cons of staying loyal. When asked by a reporter whether he

would support Blaine, he replied, "That question I decline to answer.

It is a subject I do not care to talk about." Upon leaving the convention, he complained "off the record"

to a reporter about Blaine's nomination. But, in probably the most

crucial moment of his young political career, he resisted the very

instinct to bolt from the Party that would overwhelm his political

sense in 1912. In an account of the convention, another reporter quoted

him as saying that he would give "hearty support to any decent

Democrat." He would later take great (and to some historical critics

such as Henry Pringle, rather disingenuous) pains to distance himself

from his own earlier comment, indicating that while he made it, it had

not been made "for publication." Leaving

the convention, his idealism quite disillusioned by party politics,

Roosevelt indicated that he had no further aspiration but to retire to

his ranch in the wild Badlands of the Dakota Territory that he had purchased the previous year while on a buffalo hunting expedition.

Roosevelt built a second ranch, which he named Elk Horn, thirty-five miles (56 km) north of the boomtown of Medora, North Dakota. On the banks of the Little Missouri,

Roosevelt learned to ride western style, rope, and hunt. He rebuilt his

life and began writing about frontier life for Eastern magazines. As a

deputy sheriff,

Roosevelt hunted down three outlaws who stole his river boat and were

escaping north with it up the Little Missouri. Capturing them, he

decided against hanging them (apparently yielding to established law

procedures in place of vigilante justice), and sending his foreman back by boat, he took the thieves back overland for trial in Dickinson, guarding them forty hours without sleep and reading Tolstoy to keep himself awake. When he ran out of his own books, he read a dime store western that one of the thieves was carrying." While working on a tough project aimed at hunting down a group of relentless horse thieves, Roosevelt came across the famous Deadwood sheriff, Seth Bullock. The two would remain friends for life.

After the uniquely severe U.S. winter of 1886 - 1887 wiped

out his herd of cattle (together with those of his competitors) and his

$60,000 investment, he returned to the East, where in 1885 he had built Sagamore Hill in Oyster Bay, New York.

It would be his home and estate until his death. Roosevelt ran as the

Republican candidate for mayor of New York City in 1886 as "The Cowboy

of the Dakotas"; he came in third.

Following the election, he went to London in 1886 and married his childhood sweetheart, Edith Kermit Carow. They honeymooned in Europe, and Roosevelt led a party to the summit of Mont Blanc, a feat which resulted in his induction into the British Royal Society. They had five children: Theodore Jr., Kermit, Ethel Carow, Archibald Bulloch "Archie", and Quentin. In the 1888 presidential election, Roosevelt campaigned in the Midwest for Benjamin Harrison. President Harrison appointed Roosevelt to the United States Civil Service Commission, where he served until 1895. In his term, Roosevelt vigorously fought the spoilsmen and

demanded enforcement of civil service laws. Close associate, friend and

biographer, James Bucklin Bishop, described Roosevelt's assault on the

spoils system indicating that, The

very citadel of spoils politics, the hitherto impregnable fortress that

had existed unshaken since it was erected on the foundation laid by

Andrew Jackson, was tottering to its fall under the assaults of this

audacious and irrepressible young man.... Whatever may have been the

feelings of the (fellow Republican party) President (Harrison) —

and there is little doubt that he had no idea when he appointed

Roosevelt that he would prove to be so veritable a bull in a china

shop — he refused to remove him and stood by him firmly till the end of

his term. During this time, the New York Sun described Roosevelt as "irrepressible, belligerent, and enthusiastic". In spite of Roosevelt's support for Harrison's reelection bid in the presidential election of 1892, the eventual winner, Grover Cleveland (a Bourbon Democrat), reappointed him to the same post.

Roosevelt became president of the board of New York City Police Commissioners in

1895. During his two years in this post, Roosevelt radically reformed

the police department. The police force was reputed as one of the most

corrupt in America. The NYPD's history division records that Roosevelt

was "an iron-willed leader of unimpeachable honesty, (who) brought a

reforming zeal to the New York City Police Commission in 1895." Roosevelt and his fellow commissioners established new disciplinary rules, created a bicycle squad to police New York's traffic problems, and standardized the use of pistols by officers. Roosevelt

implemented regular inspections of firearms and annual physical exams,

appointed 1,600 new recruits based on their physical and mental

qualifications and not on political affiliation, established meritorious service medals, and closed corrupt police hostelries.

During his tenure, a Municipal Lodging House was

established by the Board of Charities, and Roosevelt required officers

to register with the Board. He also had telephones installed in station houses. In 1894, Roosevelt met Jacob Riis, the muckraking Evening

Sun newspaper journalist who was opening the eyes of New York's rich to

the terrible conditions of the city's millions of poor immigrants with

such books as, How the Other Half Lives. In Riis' autobiography, he described the effect of his book on the new police commissioner, remembering that When

Roosevelt read [my] book, he came. We were not strangers. It could not

have been long after I wrote “How the Other Half Lives” that he came to

the Evening Sun office one day looking for me. I was out, and he left

his card, merely writing on the back of it that he had read my book and

had “come to help.” That was all and it tells the whole story of the

man. I loved him from the day I first saw him; nor ever in all the

years that have passed has he failed of the promise made then. No one

ever helped as he did. For two years we were brothers in (New York

City's crime ridden) Mulberry Street. When he left I had seen its

golden age. I knew too well the evil day that was coming back to have

any heart in it after that. Not that we were carried heavenward “on

flowery beds of ease” while it lasted. There is very little ease where

Theodore Roosevelt leads, as we all of us found out. The lawbreaker

found it out who predicted scornfully that he would “knuckle down to

politics the way they all did,” and lived to respect him, though he

swore at him, as the one of them all who was stronger than pull. The

peaceloving citizen who hastened to Police Headquarters with anxious

entreaties to “use discretion” in the enforcement of unpopular laws

found it out and went away with a new and breathless notion welling up

in him of an official’s sworn duty. That was it; that was what made the

age golden, that for the first time a moral purpose came into the

street. In the light of it everything was transformed. Always

an energetic man, Roosevelt made a habit of walking officers' beats

late at night and early in the morning to make sure they were on duty. As

Governor of New York State before becoming Vice President in March

1901, Roosevelt signed an act replacing the Police Commissioners with a

single Police Commissioner.

Roosevelt had always been fascinated by naval history. Urged by Roosevelt's close friend, Congressman Henry Cabot Lodge, President William McKinley appointed a delighted Roosevelt to the post of Assistant Secretary of the Navy in 1897. (Because of the inactivity of Secretary of the Navy John D. Long at the time, this gave Roosevelt control over the department.) Roosevelt was instrumental in preparing the Navy for the Spanish - American War and

was an enthusiastic proponent of testing the U.S. military in battle,

at one point stating "I should welcome almost any war, for I think this

country needs one". Upon the 1898 Declaration of War launching the Spanish - American War, Roosevelt resigned from the Navy Department. With the aid of U.S. Army Colonel Leonard Wood, Roosevelt found volunteers from cowboys from the Western territories to Ivy League friends from New York, forming the First U.S. Volunteer Cavalry Regiment. The newspapers called them the "Rough Riders." Originally Roosevelt held the rank of Lieutenant Colonel and served under Colonel Wood. In Roosevelt's own account, The Rough Riders,

"after General Young was struck down with the fever, and Wood took

charge of the brigade. This left me in command of the regiment, of

which I was very glad, for such experience as we had had is a quick

teacher." Accordingly, Wood was promoted to Brigadier General of Volunteer Forces, Roosevelt was promoted to Colonel and given command of the Regiment. Under his leadership, the Rough Riders became famous for dual charges up Kettle Hill and San Juan Hill on

July 1, 1898 (the battle was named after the latter "hill," which was

the shoulder of a ridge known as San Juan Heights). Out of all the

Rough Riders, Roosevelt was the only one with a horse – the

troopers' horses had been left behind because transport ships were in

short supply – and used it to ride back and forth between rifle

pits at the forefront of the advance up Kettle Hill; an advance which

he urged in absence of any orders from superiors. However, he was

forced to walk up the last part of Kettle Hill on foot, due to barbed

wire entanglement and after his horse, Little Texas, became tired. For his actions, Roosevelt was nominated for the Medal of Honor which was subsequently disapproved. As historian John Gable wrote,

"In later years Roosevelt would describe the Battle of San Juan Hill on

July 1, 1898, as 'the great day of my life' and 'my crowded hour.' ....

(but) Malaria and other diseases now killed more troops than had died

in battle. In August, Roosevelt and other officers demanded that the

soldiers be returned home. The famous 'round robin letter', and a

stronger letter by Roosevelt – now acting brigade commander – were leaked to the press by the commanding general, enraging Secretary of War, Russell Alger and President McKinley. Roosevelt believed that it was this incident that cost him the Medal of Honor." In September 1997, Congressman Rick Lazio,

representing the 2nd District of New York, sent two award

recommendations to the U.S. Army Military Awards Branch. These

recommendations, addressed to Brigadier General Earl Simms, the Army's

Adjutant General, and Master Sergeant Gary Soots, Chief of

Authorizations, would prove successful in garnering the much sought

after award. Roosevelt was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor in 2001 for his actions. The medal is currently on display in the Roosevelt Room of the White House. He

was the first and, thus far, the only President of the United States to

be awarded with America's highest military honor, and the only person

in history to receive both his nation's highest honor for military

valor and the world's foremost prize for peace. His oldest son, Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., would also posthumously be awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions at Normandy on June 6, 1944. After

his return to civilian life, Roosevelt preferred to be known as

"Colonel Roosevelt" or "The Colonel." As a moniker, "Teddy" remained

much more popular with the general public, despite the fact he found it

vulgar and called it "an outrageous impertinence." Political friends and others working closely with Roosevelt customarily addressed him by his rank.

On leaving the Army, Roosevelt was elected governor of New York in 1898 as a Republican. He made such an effort to root out corruption and "machine politics" that Republican boss Thomas Collier Platt forced him on McKinley as a running mate in the 1900 election, against the wishes of McKinley's manager, Senator Mark Hanna. Roosevelt was a powerful campaign asset for the Republican ticket, which defeated William Jennings Bryan in a landslide based on restoration of prosperity at home and a successful war and new prestige abroad. Bryan stumped for Free Silver again, but McKinley's promise of prosperity through the gold standard,

high tariffs, and the restoration of business confidence enlarged his

margin of victory. Bryan had strongly supported the war against Spain,

but denounced the annexation of the Philippines as

imperialism that would spoil America's innocence. Roosevelt countered

with many speeches that argued it was best for the Filipinos to have

stability, and the Americans to have a proud place in the world.

Roosevelt's six months as Vice President (March to September 1901) were

uneventful. On September 2, 1901, at the Minnesota State Fair, Roosevelt first used in a public speech a saying that would later be universally associated with him: "Speak softly and carry a big stick, and you will go far." On September 6, President McKinley was shot while at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. Initial reports in the succeeding days suggested his condition was improving, so Roosevelt embarked on a vacation at Mount Marcy in

north-eastern New York. He was returning from a climb to the summit on

September 13 when a park ranger brought him a telegram informing him

that McKinley's condition had deteriorated, and he was near death.

Roosevelt and his family immediately departed for Buffalo. When they

reached the nearest train station at North Creek,

at 5:22 a.m. on September 14, he received another telegram that

McKinley had died a few hours earlier. Roosevelt arrived in Buffalo

that afternoon, and was sworn in there as President at 3:30 p.m. Roosevelt

kept McKinley's cabinet and promised to continue McKinley's policies.

One of his first notable acts as president was to deliver a 20,000-word

address to Congress asking it to curb the power of large corporations (called "trusts"). For his aggressive attacks on trusts over his two terms he has been called a "trust-buster." In the 1904 presidential election, Roosevelt won the presidency in his own right in a landslide victory. His vice president was Charles Fairbanks. Roosevelt dealt with union workers also. In May 1902, United Mine Workers went

on strike to get higher pay wages and shorter work days. He set up a

fact-finding commission which stopped the strike, and resulted in the

workers getting more pay for fewer hours. In August 1902, Roosevelt was the first president to be seen riding in an automobile in public. This

took place in Hartford, CT. The car was a Columbia Electric Victoria

Phaeton, manufactured in Hartford. The police squad which surrounded

the car rode bicycles. In 1905, he issued a corollary to the Monroe Doctrine,

which allows the United States to "exercise international policy power"

so they can intervene and keep smaller countries on their feet. In his book The Imperial Cruise (2009),

author James Bradley reveals that in 1905 Roosevelt encouraged the

Japanese to begin their military expansion onto the Asian continent

when the president agreed a secret treaty that allowed Japan to take

Korea. Bradley asserts that with this secret and unconstitutional

maneuver, Roosevelt inadvertently ignited the problem (Japanese

expansionism in Asia) that Franklin Delano Roosevelt would later confront as WWII in Asia. The New York Times published a complementary review, writing that "The Imperial Cruise is startling enough to reshape conventional wisdom about Roosevelt’s presidency." Roosevelt helped the well being of people by passing laws such as The Meat Inspection Act of 1906 and The Pure Food and Drug Act.

The Meat Inspection Act of 1906 banned misleading labels and

preservatives that contained harmful chemicals. The Pure Food and Drug

Act banned food and drugs, that are impure or falsely labeled, from

being made, sold, and shipped. The Gentlemen's Agreement with

Japan came into play in 1907, banning all school segregation of

Japanese, yet controlling Japanese immigration in California. That

year, Roosevelt signed the proclamation establishing Oklahoma as the 46th state of the Union. Building on McKinley's effective use of the press, Roosevelt made the White House the

center of news every day, providing interviews and photo opportunities.

After noticing the White House reporters huddled outside in the rain

one day, he gave them their own room inside, effectively inventing the

presidential press briefing. The grateful press, with unprecedented access to the White House, rewarded Roosevelt with ample coverage. He chose not to run for another term in 1908, and supported William Taft for

the presidency, instead of Fairbanks. Fairbanks withdrew from the race,

and would later support Taft for re-election against Roosevelt in the 1912 election. In total Roosevelt appointed 75 federal judges, a record for his day surpassing the 46 appointed by Ulysses S. Grant. Roosevelt appointed three Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States: Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. (1902), William Rufus Day (1903), William Henry Moody (1906). In addition to these three, Roosevelt appointed 19 judges to the United States Courts of Appeals, and 53 judges to the United States district courts. Five of Roosevelt's appointees - George Bethune Adams, Thomas H. Anderson, Robert W. Archbald, Andrew McConnell, January Cochran, and Benjamin Franklin Keller, were originally placed on their respective courts as recess appointments by

President McKinley. Following the assassination which resulted in

McKinley's death on September 14, 1901, Roosevelt chose to formally

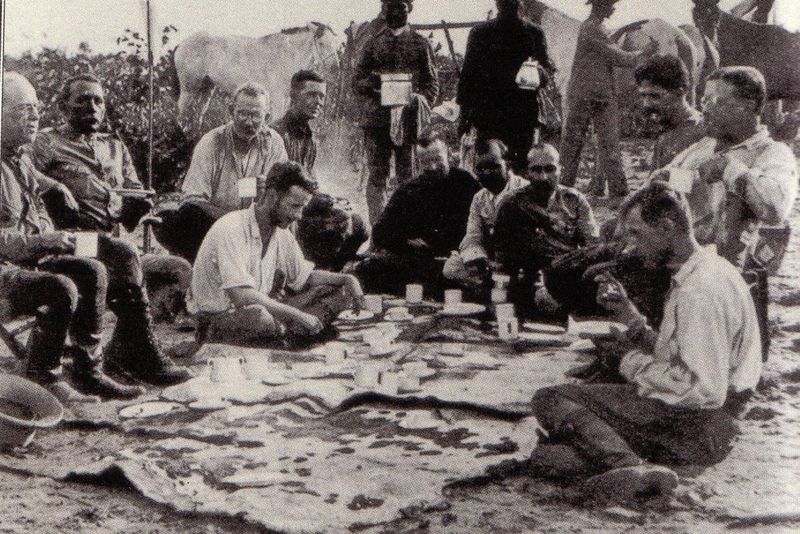

nominate those judges for confirmation by the United States Senate, and all were confirmed. In March 1909, shortly after the end of his presidency, Roosevelt left New York for a safari in east and central Africa. Roosevelt's party landed in Mombasa, British East Africa (now Kenya), traveled to the Belgian Congo (now Democratic Republic of the Congo) before following the Nile up to Khartoum in modern Sudan. Financed by Andrew Carnegie and by his own proposed writings, Roosevelt's party hunted for specimens for the Smithsonian Institution and for the American Museum of Natural History in New York. The group included scientists from the Smithsonian and was led by the legendary hunter tracker R.J. Cunninghame and was joined from time to time by Frederick Selous,

the famous big game hunter and explorer. Among other items, Roosevelt

brought with him four tons of salt for preserving animal hides, a lucky

rabbit's foot given to him by boxer John L. Sullivan,

an elephant rifle donated by a group of 56 admiring Britons, and the

famous Pigskin Library, a collection of classics bound in pig leather

and transported in a single reinforced trunk. All told, Roosevelt and

his companions killed or trapped more than 11,397 animals, from insects and moles to hippopotamuses and elephants. These included 512 big game animals, including six rare white rhinos. The expedition consumed 262 of the animals. Tons of salted animals and their skins were shipped to Washington; the quantity was so large that it took years to mount them all, and the Smithsonian was able to share many duplicate animals with other museums. Regarding the large number of animals taken, Roosevelt said, "I can be condemned only if the existence of the National Museum, the American Museum of Natural History, and all similar zoological institutions are to be condemned." Although the safari was ostensibly conducted in the name of science,

it was as much a political and social event as it was a hunting

excursion; Roosevelt interacted with renowned professional hunters and

land-owning families, and made contact with many native peoples and

local leaders. He later wrote a detailed account in the book African Game Trails, where he describes the excitement of the chase, the people he met, and the flora and fauna he collected in the name of science.

Roosevelt certified William Howard Taft to be a genuine "progressive" in 1908,

when Roosevelt pushed through the nomination of his Secretary of War

for the Presidency. Taft easily defeated three-time candidate William Jennings Bryan.

Taft promoted a different progressivism, one that stressed the rule of

law and preferred that judges rather than administrators or politicians

make the basic decisions about fairness. Taft usually proved a less

adroit politician than Roosevelt and lacked the energy and personal

magnetism, not to mention the publicity devices, the dedicated

supporters, and the broad base of public support that made Roosevelt so

formidable. When Roosevelt realized that lowering the tariff would risk

severe tensions inside the Republican Party — pitting producers

(manufacturers and farmers) against merchants and consumers — he stopped

talking about the issue. Taft ignored the risks and tackled the tariff

boldly, on the one hand encouraging reformers to fight for lower rates,

and then cutting deals with conservative leaders that kept overall rates high. The resulting Payne - Aldrich tariff of 1909 was too high for most reformers, but instead of blaming this on Senator Nelson Aldrich and

big business, Taft took credit, calling it the best tariff ever. Again

he had managed to alienate all sides. While the crisis was building

inside the Party, Roosevelt was touring Africa and Europe, to allow

Taft to be his own man. Unlike

Roosevelt, Taft never attacked business or businessmen in his rhetoric.

However, he was attentive to the law, so he launched 90 antitrust

suits, including one against the largest corporation, U.S. Steel, for

an acquisition that Roosevelt had personally approved. Consequently,

Taft lost the support of antitrust reformers (who disliked his

conservative rhetoric), of big business (which disliked his actions),

and of Roosevelt, who felt humiliated by his protégé. The

left wing of the Republican Party began agitating against Taft. Senator Robert LaFollette of Wisconsin created the National Progressive Republican League (precursor to the Progressive Party (United States, 1924)) to defeat the power of political bossism at the state level and to

replace Taft at the national level. More trouble came when Taft fired Gifford Pinchot, a leading conservationist and close ally of Roosevelt. Pinchot alleged that Taft's Secretary of Interior Richard Ballinger was in league with big timber interests. Conservationists sided with Pinchot, and Taft alienated yet another vocal constituency. Roosevelt,

back from Europe, unexpectedly launched an attack on the courts. His

famous speech at Osawatomie, Kansas, in August 1910 was the most

radical of his career and openly marked his break with the Taft

administration and the conservative Republicans. Osawatomie was well

known as the base used by John Brown when

he launched his bloody attacks on slavery. Taft was deeply upset.

Roosevelt was attacking both the judiciary and the deep faith

Republicans had in their judges (most of whom had been appointed by

McKinley, Roosevelt or Taft.) In the 1910 Congressional elections,

Democrats swept to power, and Taft's reelection in 1912 was

increasingly in doubt. In 1911, Taft responded with a vigorous stumping

tour that allowed him to sign up most of the party leaders long before Roosevelt announced. Late

in 1911, Roosevelt finally broke with Taft and LaFollette and announced

himself as a candidate for the Republican nomination. Roosevelt,

however, had delayed too long, and Taft had already won the support of

most party leaders in the country. Because of LaFollette's nervous

breakdown on the campaign trail before Roosevelt's entry, most of

LaFollette's supporters went over to Roosevelt, the new progressive

Republican candidate. Roosevelt,

stepping up his attack on judges, carried nine of the states that held

preferential primaries, LaFollette took two, and Taft only one. The

1912 primaries represented the first extensive use of the presidential primary,

a reform achievement of the progressive movement. However, these

primary elections, while demonstrating Roosevelt's continuing

popularity with the electorate, were not nearly as pivotal as primaries

became later in the century. There were fewer states where a common

voter had an opportunity to express a recorded preference. Many more

states selected convention delegates at state party conventions, or in

caucuses, which were not as open as they later became. While Roosevelt

was popular with the public, most Republican politicians and party

leaders supported Taft, and their support proved difficult to counter

in states without primaries. At the Republican Convention in Chicago,

despite being the incumbent, Taft's victory was not immediately

assured. After two weeks, Roosevelt, realizing he would not be able to

win the nomination outright, asked his followers to leave the

convention hall. They moved to the Auditorium Theatre, and then Roosevelt, along with key allies such as Pinchot and Albert Beveridge created the Progressive Party,

structuring it as a permanent organization that would field complete

tickets at the presidential and state level. It was popularly known as

the "Bull Moose Party", which got its name after Roosevelt told reporters, "I'm as fit as a bull moose." At the convention Roosevelt cried out, "We stand at Armageddon and

we battle for the Lord." Roosevelt's platform echoed his 1907 – 08

proposals, calling for vigorous government intervention to protect the

people from the selfish interests. To destroy this invisible Government, to dissolve the unholy alliance between corrupt business and corrupt politics is the first task of the statesmanship of the day." - 1912 Progressive Party Platform, attributed to him and quoted again in his autobiography where

he continues "'This country belongs to the people. Its resources, its

business, its laws, its institutions, should be utilized, maintained,

or altered in whatever manner will best promote the general interest.'

This assertion is explicit. ... Mr. Wilson must know that every monopoly in

the United States opposes the Progressive party. ... I challenge him

... to name the monopoly that did support the Progressive party,

whether ... the Sugar Trust, the Steel Trust, the Harvester Trust, the Standard Oil Trust,

the Tobacco Trust, or any other. ... Ours was the only programme to

which they objected, and they supported either Mr. Wilson or Mr. Taft... While Roosevelt was campaigning in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, on October 14, 1912, a saloonkeeper named John Schrank shot

him, but the bullet lodged in his chest only after penetrating both his

steel eyeglass case and passing through a thick (50 pages)

single-folded copy of the speech he was carrying in his jacket. Roosevelt,

as an experienced hunter and anatomist, correctly concluded that since

he wasn't coughing blood, the bullet had not completely penetrated the

chest wall to his lung, and so declined suggestions he go to the

hospital immediately. Instead, he delivered his scheduled speech with

blood seeping into his shirt. He spoke for 90 minutes.

His opening comments to the gathered crowd were, "Ladies and gentlemen,

I don't know whether you fully understand that I have just been shot;

but it takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose." Afterwards,

probes and x-ray showed that the bullet had traversed three inches

(76 mm) of tissue and lodged in Roosevelt's chest muscle but did

not penetrate the pleura,

and it would be more dangerous to attempt to remove the bullet than to

leave it in place. Roosevelt carried it with him for the rest of his

life. Due

to the bullet wound, Roosevelt was taken off the campaign trail in the

final weeks of the race (which ended election day, November 5). Though

the other two campaigners stopped their own campaigns in the week

Roosevelt was in the hospital, they resumed it once he was released.

The overall effect of the shooting was uncertain. Roosevelt for many

reasons failed to move enough Republicans in his direction. He did win

4.1 million votes (27%), compared to Taft's 3.5 million

(23%). However, Wilson's 6.3 million votes (42%) were enough to

garner 435 electoral votes. Roosevelt had 88 electoral votes to Taft's

8 electoral votes. (This meant that Taft became the only incumbent President in history to come in third place in an attempt to be re-elected.) But Pennsylvania was Roosevelt's only eastern state; in the Midwest he carried Michigan, Minnesota and South Dakota; in the West, California and Washington; he did not win any southern states. Although he lost, he won more votes than former presidents Martin Van Buren and Millard Fillmore who also ran again and also lost.

Roosevelt's popular book Through the Brazilian Wilderness describes his expedition into the Brazilian jungle in 1913 as a member of the Roosevelt - Rondon Scientific Expedition, co-named after its leader, Brazilian explorer Cândido Rondon.

The book describes the scientific discovery, scenic tropical vistas,

and exotic flora and fauna experienced during the adventure. A friend,

Father John Augustine Zahm,

had searched for new adventures and found them in the forests of South

America. After a briefing of several of his own expeditions, he

persuaded Roosevelt to commit to such an expedition in 1912. To finance

the expedition Roosevelt received support from the American Museum of Natural History, promising to bring back many new animal specimens. Once in South America a new far more ambitious goal was added: to find the headwaters of the Rio da Duvida, the River of Doubt, and trace it north to the Madeira and thence to the Amazon River. It was later renamed Roosevelt River in

honor of the former President. Roosevelt's crew consisted of his

24 year old son Kermit, Colonel Rondon, a naturalist, George K.

Cherrie, sent by the American Museum of Natural History,

Brazilian Lieutenant Joao Lyra, team physician Dr. José Antonio

Cajazeira, and 16 skilled paddlers and porters (called camaradas in Portuguese).

The initial expedition started, probably unwisely, on December 9, 1913,

at the height of the rainy season. The trip down the River of Doubt

started on February 27, 1914.

During the trip down the river, Roosevelt contracted malaria and

a serious infection resulting from a minor leg wound. These illnesses

so weakened Roosevelt that six weeks into the adventure he had to be

attended day and night by the expedition's physician and his son,

Kermit. By then he was unable to walk due both to the infection in his

injured leg and an infirmity in his other owing to a traffic accident a

decade earlier, riddled with chest pains, fighting a fever that soared

to 103 °F (39 °C), and at times delirious. In fact,

Roosevelt was so delirious that he would repeat endlessly the opening

line from Coleridge's poem Kubla Khan. Regarding

his condition as a threat to the survival of the others, Roosevelt

insisted he be left behind to allow the by then poorly provisioned

expedition to proceed as rapidly as it could. Only an appeal by his son

convinced him to continue. In

spite of his continued decline and loss of what ultimately amounted to

over 50 pounds (20 kg) of his original 220, Commander Rondon had

been repeatedly slowing down the pace of the expedition in dedication

to his commission's mapmaking and other geographical goals that

demanded regular stops to fix the expedition's position by sun based

survey. Upon

Roosevelt's return to New York, friends and family were startled by his

physical appearance and fatigue. Roosevelt wrote to a friend that the

trip had cut his life short by ten years. He might not have really

known just how accurate that analysis would prove: for the rest of his

few remaining years he would be plagued by flareups of malaria and leg

inflammations so severe that they would require surgery. Before

Roosevelt had even completed his sea voyage home, doubts were raised

over his claims of exploring and navigating a completely uncharted

river over 625 miles (1,000 km) long. When he had recovered

sufficiently he addressed a standing room only convention organized in

Washington, D.C. by the National Geographic Society and satisfactorily defended his claims. The River of Doubt later was named the Rio Roosevelt. When World War I began in 1914, Roosevelt strongly supported the Allies and demanded a harsher policy against Germany, especially regarding submarine warfare. Roosevelt angrily denounced the foreign policy of President Wilson, calling it a failure regarding the atrocities in Belgium and the violations of American rights. In 1916, he campaigned energetically for Charles Evans Hughes and

repeatedly denounced Irish - Americans and German - Americans who Roosevelt

said were unpatriotic because they put the interest of Ireland and

Germany ahead of America's by supporting neutrality. He insisted one

had to be 100% American, not a "hyphenated American" who juggled multiple loyalties. When the U.S. entered the war in 1917,

Roosevelt sought to raise a volunteer infantry division, but Wilson

refused. Roosevelt's

attacks on Wilson helped the Republicans win control of Congress in the

off-year elections of 1918. Roosevelt was popular enough to seriously

contest the 1920 Republican nomination, but his health was broken by

1918, because of the lingering malaria. His family and supporters threw their support to Roosevelt's old military companion, General Leonard Wood, who was ultimately defeated by Warren G. Harding. His son Quentin,

a daring pilot with the American forces in France, was shot down behind

German lines in 1918. Quentin was his youngest son and probably his

favorite. It is said the death of his son distressed him so much that

Roosevelt never recovered from his loss. Despite his faltering health, Roosevelt remained active to the end of his life. He was an enthusiastic proponent of the Scouting movement. The Boy Scouts of America gave him the title of Chief Scout Citizen,

the only person to hold such title. One early Scout leader said, "The

two things that gave Scouting great impetus and made it very popular

were the uniform and Teddy Roosevelt's jingoism." On January 6, 1919, Roosevelt died in his sleep at Oyster Bay of a coronary thrombosis (heart attack), preceded by a 2½-month illness described as inflammatory rheumatism, and was buried in nearby Youngs Memorial Cemetery. Upon receiving word of his death, his son Archie telegraphed his siblings simply, "The old lion is dead." The U.S. Vice-President at that time, Thomas R. Marshall, said that "Death had to take Roosevelt sleeping, for if he had been awake, there would have been a fight." Theodore Roosevelt introduced the phrase "Square Deal" to describe his progressive views in a speech delivered

after leaving the office of the Presidency in August 1910. In his broad

outline, he stressed equality of opportunity for all citizens and

emphasized the importance of fair government regulations of corporate

'special interests'. Roosevelt was one of the first Presidents to make conservation a national issue. In a speech that

Roosevelt gave at Osawatomie, Kansas, on August 31, 1910, he outlined

his views on conservation of the lands of the United States. He favored

the use of America's natural resources, but not the misuse of them

through wasteful consumption. One

of his most lasting legacies was his significant role in the creation

of 150 National Forests, five national parks, and 18 national

monuments, among other works of conservation. In total, Roosevelt was

instrumental in the conservation of approximately 230 million acres (930,000 km2) of American soil among various parks and other federal projects. In the Eighth Annual Message to Congress (1908),

Roosevelt mentioned the need for federal government to regulate

interstate corporations using the Interstate Commerce Clause, also

mentioning how these corporations fought federal control by appealing

to states' rights. In

an 1894 article on immigration, Roosevelt said, "We must Americanize in

every way, in speech, in political ideas and principles, and in their

way of looking at relations between church and state. We welcome the

German and the Irishman who becomes an American. We have no use for the

German or Irishman who remains such... He must revere only our flag,

not only must it come first, but no other flag should even come second." Roosevelt

was the first president to appoint a representative of the Jewish

minority to a cabinet position, Secretary of Commerce and Labor, Oscar

S. Straus, 1906 - 09. In

1886 he said: "I don't go so far as to think that the only good Indians

are dead Indians, but I believe nine out of ten are, and I shouldn't

like to inquire too closely into the case of the tenth." He later

became much more favorable. With

regard to African Americans Roosevelt said, "I have not been able to

think out any solution of the terrible problem offered by the presence

of the Negro on this continent, but of one thing I am sure, and that is

that inasmuch as he is here and can neither be killed nor driven away,

the only wise and honorable and Christian thing to do is to treat each

black man and each white man strictly on his merits as a man, giving

him no more and no less that he shows himself worthy to have." Starting in 1907 eugenicists in

many States started the forced sterilization of the sick, unemployed,

poor, criminals, prostitutes, and the disabled. Roosevelt said in 1914:

"I wish very much that the wrong people could be prevented entirely

from breeding; and when the evil nature of these people is sufficiently

flagrant, this should be done. Criminals should be sterilized and

feeble minded persons forbidden to leave offspring behind them." Roosevelt

was a prolific author, writing with passion on subjects ranging from

foreign policy to the importance of the national park system. As an

editor of Outlook magazine,

he had weekly access to a large, educated national audience. In all,

Roosevelt wrote about 18 books (each in several editions), including his Autobiography, The Rough Riders, History of the Naval War of 1812, and others on subjects such as ranching, explorations, and wildlife. His most ambitious book was the four volume narrative The Winning of the West,

which connected the origin of a new "race" of Americans (i.e. what he

considered the present population of the United States to be) to the

frontier conditions their ancestors endured throughout the 17th, 18th,

and early 19th centuries. In 1907, Roosevelt became embroiled in a widely publicized literary debate known as the nature fakers controversy. A few years earlier, naturalist John Burroughs had published an article entitled "Real and Sham Natural History" in the Atlantic Monthly, attacking popular writers of the day such as Ernest Thompson Seton, Charles G.D. Roberts and William J. Long for

their fantastical representations of wildlife. Roosevelt agreed with

Burroughs' criticisms, and published several essays of his own

denouncing the booming genre of "naturalistic" animal stories as

"yellow journalism of the woods". It was the President himself who

popularized the negative term "nature faker" to describe writers who

depicted their animal characters with excessive anthropomorphism. Roosevelt

intensely disliked being called "Teddy," and was quick to point out

this fact to those who used the nickname, though it would become widely

used by newspapers during his political career. He attended church

regularly. Of including the motto "In God We Trust" on money, in 1907

he wrote, "It seems to me eminently unwise to cheapen such a motto by

use on coins, just as it would be to cheapen it by use on postage

stamps, or in advertisements." He was also a member of the Freemasons and Sons of the American Revolution. Roosevelt had a lifelong interest in pursuing what he called, in an 1899 speech, "the strenuous life". To this end, he exercised regularly and took up boxing, tennis, hiking, rowing, polo, and horseback riding.

As governor of New York, he boxed with sparring partners several times

a week, a practice he regularly continued as President until one blow

detached his left retina, leaving him blind in that eye (a fact not made public until many years later). Thereafter, he practiced judo attaining a third degree brown belt and continued his habit of skinny dipping in the Potomac River during winter. He was an enthusiastic singlestick player and, according to Harper's Weekly, in 1905 showed up at a White House reception with his arm bandaged after a bout with General Leonard Wood. Roosevelt

was also an avid reader, reading tens of thousands of books, at a rate

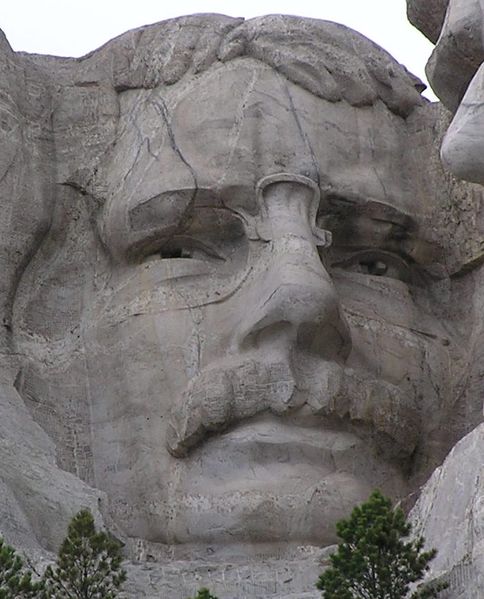

of several a day in multiple languages. Along with Thomas Jefferson, Roosevelt is often considered the most well read of any American politician. Roosevelt was included with George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln at the Mount Rushmore Memorial, designed in 1927 with the approval of Republican President Calvin Coolidge. For his gallantry at San Juan Hill, Roosevelt's commanders recommended him for the Medal of Honor. In the late 1990s, Roosevelt's supporters again took up the flag for him. On January 16, 2001, President Bill Clinton awarded

Theodore Roosevelt the Medal of Honor posthumously for his charge up

San Juan Hill, Cuba, during the Spanish - American War. Roosevelt's

eldest son, Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., received the Medal of Honor for heroism at the Battle of Normandy in 1944. The Roosevelts thus became one of only two father - son pairs to receive this honor. Roosevelt's legacy includes several other important commemorations. The United States Navy named two ships for Roosevelt: the USS Theodore Roosevelt, a submarine that was in commission from 1961 to 1982; and the USS Theodore Roosevelt, an aircraft carrier that has been on active duty in the Atlantic Fleet since 1986. On November 18, 1956, the United States Postal Service released a 6¢ Liberty Issue postage stamp honoring Roosevelt. The Roosevelt Memorial Association (later the Theodore Roosevelt Association) or "TRA", was founded in 1920 to preserve Roosevelt's legacy. The Association preserved Roosevelt's birthplace, "Sagamore Hill" home, papers, and video film. In 1941, it published the Theodore Roosevelt Cyclopedia, a compendium of Roosevelt's key writings, sayings and conversations, which is available online. Among the hundreds of schools and streets named in Roosevelt's honor are Roosevelt High School in Seattle, Washington, the surrounding Roosevelt neighborhood, the district's main arterial, Roosevelt Way N.E., and Roosevelt Middle School in Eugene, Oregon.

Historians

credit Roosevelt for changing the nation's political system by

permanently placing the presidency at center stage and making character

as important as the issues. His notable accomplishments include

trust busting and conservationism. However, he has been criticized for

his interventionist and imperialist approach to nations he considered

"uncivilized". Even so, history and legend have been kind to him. His

friend, historian Henry Adams,

proclaimed, "Roosevelt, more than any other living man .... showed the

singular primitive quality that belongs to ultimate matter – the

quality that mediaeval theology assigned to God – he was pure

act." Historians typically rank Roosevelt among the top five presidents.

The Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel in Los Angeles is named after him, as is the Roosevelt Hotel in New York City. In Chicago, the city renamed 12th Street to Roosevelt Road. In Philadelphia, Roosevelt Boulevard, also known as U.S. 1, was named in his honor in 1918.