<Back to Index>

- Physician Auguste Henri Forel, 1848

- Composer Engelbert Humperdinck, 1854

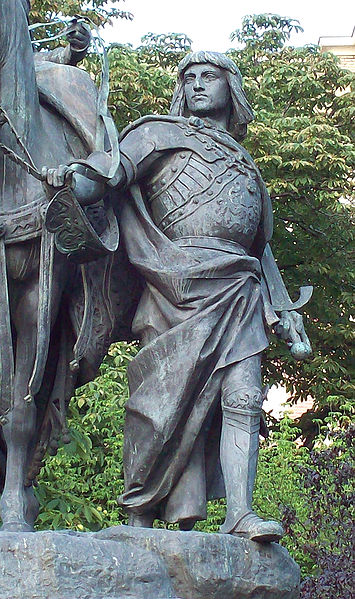

- Spanish General Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba, 1453

PAGE SPONSOR

Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba, Duke of Terranova and Santangelo, Andria, Montalto and Sessa, also known as Gonzalo de Córdoba (Italian: Gonsalvo or Consalvo di Cordova; September 1, 1453 – December 2, 1515) was a Spanish general fighting in the times of the Conquest of Granada and at the Italian Wars reputed to be "the Father of Trench Warfare" and the infantry units which were later known as tercio.

He was born at Montilla, in what is now the province of Córdoba, a cadet son of Pedro Fernández de Córdoba, count of Aguilar, and his wife Elvira de Herrera. He and his elder brother, Alonso, became orphans while very young boys. The counts of Aguilar carried on an hereditary feud with the rival house of Cabra, in spite of both family branches coming from a same family tree. As a cadet child within the family, he could not expect much on the way of inherited wealth or titles, having, as nearly always then, to try a church or a military career, the latter being more satisfactory to his wishes. He was first attached to the household of Don Alfonso, the king's half brother, and upon his death devoted himself to Prince Alfonso utherine sister, Isabel of Castile, who later, mediating a civil war, had proclaimed herself successor queen in 1474, disputing the right of her niece, Juana, to ascend the throne.

During the ensuing civil war between the followers of the daughter of deceased king Henry IV of Castile, Juana la Beltraneja, and the king's half sister Princess Isabella of Castile, there were conflicts with Portugal as the king of Portugal Afonso V of Portugal sided on the war to protect his 13 years old niece, Juana, he fought under the grand master of the Order of Santiago, Alonso de Cárdenas. After the battle of Albuera, the grand master gave him special praise for his behavior.

During the ten-year long conquest of Granada under the Catholic Monarchs, he completed his apprenticeship under his brother Alonso, the grand master of Santiago, Alonso de Cardenas, and the counts of Aguilar and of Tendilla, of whom he spoke always as his masters. It was a war of sieges and the defence of castles or towns, of skirmishes, and of ambushes in the defiles of the mountains. The skills of a military engineer and a guerilla fighter were equally employed. Córdoba's most distinguished feat was the defence of the advanced post of Íllora. Able to speak Berber Arabic, the language of the emirate, he was chosen as one of the officers to arrange the capitulation, and, with the peace of 1492, was rewarded with a grant of land in the town of Loja, near the city of Granada.

He

married, as a widower, one of the ladies in waiting to Queen Isabella I

of Castilla, namely, Luisa Manrique de Lara, on 14 February 1489, when

he was already aged 36 . His surviving only daughter, Elvira Fernández de Córdoba y Manrique,

would inherit all their titles on his death in 1515. In order to keep,

hopefully, her father's name, she married within the close family, just

with someone from a long time antagonistic branch but bearing also her

own family name, "Fernández de Córdoba". When the Catholic Monarchs decided to support the Aragonese house of Naples against Charles VIII of France,

Gonzalo, in his mid forties, was chosen by the influence of the queen,

and in preference to older men, to command the Spanish expedition. In

Italy, he won the title of the Great Captain. Italian historian Francesco Guicciardini says

that it was given him by the customary arrogance of the Spaniards. He

held the command in Italy twice. In 1495 he was sent with a small force

of little more than five thousand men to aid Ferdinand I of Naples, by then brother in law of king Ferdinand II of Aragon to recover his kingdom. His first battle in Italy at Seminara in 1495, resulted in defeat at the hands of the French led by Bernard Stewart d'Aubigny. The following year, avoiding pitched battle, he captured the rebel county of Alvito for the king, driving the French back to Calabria. He

returned home in 1498. After a brief interval of service against the

conquered Moors who had risen in revolt, he was back to Italy in 1501.

Ferdinand II of Aragon had entered into his apparently iniquitous

compact with Louis XII of France for

the spoliation and division of the kingdom of Naples. The Great Captain

was chosen to command the Spanish part of the coalition. As general and

as viceroy of Naples he remained in Italy till 1507. During his first command he was mostly employed in Calabria in mountain warfare which bore much resemblance to his former experience in Granada. There was,

however, a material difference in the enemy. The French forces under

d'Aubigny consisted largely of Swiss mercenary pikemen, and of their own men-at-arms, the heavily armoured professional cavalry, the gendarmes.

With his veterans of the Granadine war, foot soldiers armed with sword

and buckler, or arquebuses and crossbows, and light cavalry, who

possessed endurance unparalleled among the soldiers of the time, he

could carry on a guerrilla-like warfare which wore down his opponents,

who suffered far more than the Spaniards from the heat. His experience at Seminara showed

him that something more was wanted on the battlefield. The action was

lost mainly because Ferdinand, disregarding the advice of Gonzalo,

persisted in fighting a pitched battle with their more lightly equipped

troops. In the open field, the loose formation and short swords of the

Spanish infantry put them at a disadvantage against a charge of heavy

cavalry or pikemen. Gonzalo therefore introduced a closer formation,

and divided the Spanish infantry into the battle or main central body

of pikemen, and the wings of shot, called a colunella - the original pike and shot formation. The

French were expelled by 1498 without another battle, king Charles VIII

of France diyng in April 1498. When the Great Captain reappeared in

Italy he had first to perform the congenial task of driving the Turks out of Kefalonia, together with such condottieri as Pedro Navarro, helping the Venetian navy to reconquer the Castle of Saint Georges, 25 december 1500, killing there over 300 people including Albanian born Gisdar, to aid in the campaign against Frederick IV of Naples. When

the king of Naples had been deposed, the French and Spaniards engaged

in a guerilla war while they negotiated the partition of the kingdom.

The Great Captain now found himself with a much outnumbered army

besieged in Barletta by

the French. The war was divided into two phases very similar to one

another. During the end of 1502 and the early part of 1503 the

Spaniards were besieged in Barletta near the Ofanto on the shores of the Adriatic.

Cordoba resolutely refused to be tempted into battle either by the

taunts of the French or the discontent of his own soldiers. Meanwhile

he employed the Aragonese partisans in the country, and flying

expeditions of his own men, to harass the enemy's communications and

distracted his men with a tournament between Italian knights under Ettore Fieramosca and

French prisoners. When

he was reinforced, and the French committed the mistake of spreading

out their forces to forage for supplies, he took the offensive, and

pounced on his enemies supply depot in the Cerignola,

there he took up a strong defensive position (he was still outnumbered

three to one), there he threw up hasty field works, and strengthened

them with a species of wire entanglements. The French made a headlong

front attack, were repulsed, assailed in flank, and routed in only half

an hour by the combination of firepower and defensive measures. Later

operations on the Garigliano against Ludovico II of Saluzzo were very similar, and led to the total expulsion of the French from the Kingdom of Naples.

Cordoba was appointed Viceroy of Naples in

1504. However, his fame aroused the jealousy of so typical a

renaissance monarch as Ferdinand II of Aragon. Furthermore, Cordoba was

profligate in using the public treasury to reward his captains and

soldiers. The death of queen Isabel I in 1504 deprived him of a friend

and protector and in 1507 he was recalled. Ferdinand loaded him with

titles and fine words, but left him unemployed till his death. Córdoba

was first among the founders of modern warfare. As a field commander,

Córdoba, like Napoleon three centuries later, saw his goal in

the destruction of the enemy army. He systematically organized the

pursuit of defeated armies after a victory in order to destroy the

retreating enemy. Córdoba helped found the first modern standing

army and the nearly invincible Spanish infantry that dominated

battlefields of Europe during the 16th and the first decades of the

17th century. The best generals of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and Philip II of Spain were either the pupils of the Great Captain or were trained by them. Córdoba's influence upon tactics was profound. Wellington's Torres Vedras campaign has a distinct resemblance to Córdoba's campaign at Barletta and the Battle of Assaye is easily compared with that at Garigliano. He left no sons, so he was succeeded in his dukedoms by his daughter, Elvira Fernández de Córdoba y Manrique. His burial place, Monastery of San Jerónimo, Granada,

is a magnificent piece of Renaissance Architecture built by his wife

and daughter. It was desecrated by French Napoleonic troops under the

command of Corsican General Sebastiani at the beginning of the 19th century. Stone from the tower was used to build the "Puente Verde" bridge over the river Genil. The monastery was fully restored at the end of the 19th century.

Gonzalo's renown in Spain was great and many of the conquistadors admired him, some even imitating his dress fashion. Many had served under him like Amador de Lares who was steward to the Great Captain.