<Back to Index>

- Engineer Ferdinand Porsche, 1875

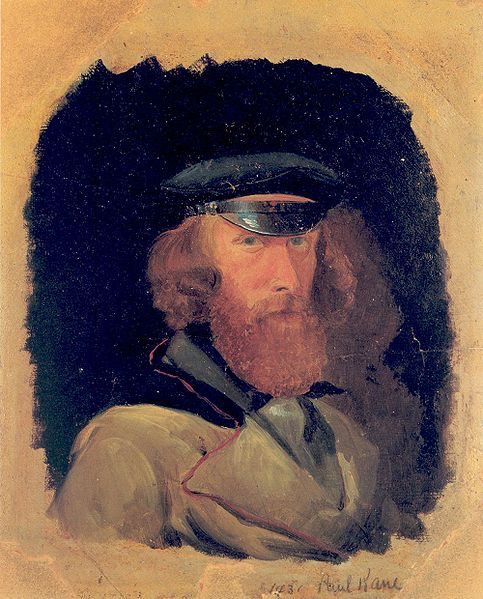

- Painter Paul Kane, 1810

- French Socialist Leader Auguste Marie Joseph Jean Léon Jaurès, 1859

PAGE SPONSOR

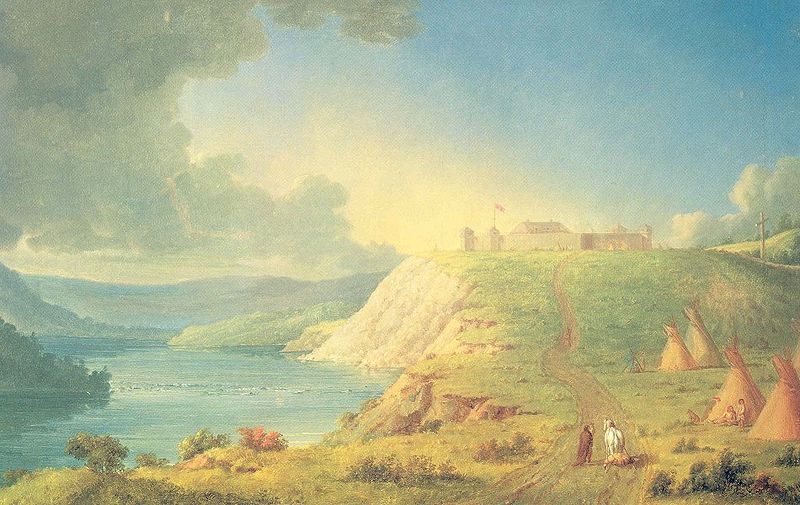

Paul Kane (September 3, 1810 – February 20, 1871) was an Irish-born Canadian painter, famous for his paintings of First Nations peoples in the Canadian West and other Native Americans in the Oregon Country.

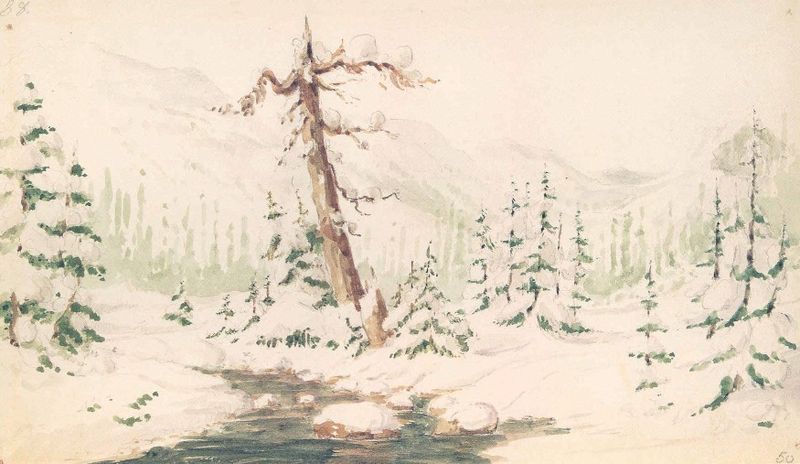

A largely self-educated artist, Kane grew up in Toronto (then known as York) and trained himself by copying European masters on a study trip through Europe. He undertook two voyages through the wild Canadian northwest in 1845 and from 1846 to 1848. The first trip took him from Toronto to Sault Ste. Marie and back. Having secured the support of the Hudson's Bay Company, he set out on a second, much longer voyage from Toronto across the Rocky Mountains to Fort Vancouver and Fort Victoria in the Columbia District, as the Canadians called the Oregon Country. On both trips Kane sketched and painted Aboriginal peoples and documented their lives. Upon his return to Toronto, he produced more than one hundred oil paintings from these sketches. Kane's work, particularly his field sketches, are still a valuable resource for ethnologists. The oil paintings he completed in his studio are considered a part of the Canadian heritage, although he often embellished them considerably, departing from the accuracy of his field sketches in favour of more dramatic scenes.

Kane was born in Mallow, County Cork in Ireland, the fifth child of the eight children of Michael Kane and Frances Loach. His father, a soldier from Preston, Lancashire, England,

served in the Royal Horse Artillery until his discharge in 1801. The

family then settled in Ireland. Sometime between 1819 and 1822, they

immigrated to Upper Canada and settled in York, which would later, in March 1834, become Toronto. There, Kane's father operated a shop as a spirits and wine merchant. Not

much is known about Kane's youth in York, which at that time was a

small settlement of a few thousand people. He went to school at Upper Canada College, and then received some training in painting by an art teacher named Thomas Drury at the Upper Canada College around

1830. In July 1834, he displayed some of his paintings in the first

(and only) exhibition of The Society of Artists and Amateurs in

Toronto, gaining a favourable review by a local newspaper, The Patriot.

Kane began a career as a sign and furniture painter at York, moving to Cobourg, Ontario, in 1834. At Cobourg, he took up a job in the furniture factory of Freeman Schermerhorn Clench, but also painted several portraits of the local personalities, including the sheriff and his employer's wife. In 1836 Kane moved to Detroit, Michigan, where the American artist James Bowman was living. The two had met earlier at York. Bowman had persuaded Kane that studying art in Europe was

a necessity for an aspiring painter, and they had planned to travel to

Europe together. But Kane had to postpone the trip, as he was short of

money to pay for the passage to Europe and Bowman had married shortly

before and was not inclined to leave his family. For the next five

years, Kane toured the American Midwest, working as an itinerant portrait painter, travelling to New Orleans. In June 1841, Kane left America, sailing from New Orleans aboard a ship bound for Marseilles in France, arriving there about three months later. Unable to afford formal art studies at an art school or with an established master, he toured Europe for the next two years, visiting art museums wherever he could and studying and copying the works of old masters. Until autumn 1842 he stayed in Italy, before trekking across the Great St. Bernard Pass, moving to Paris and from there on to London. In London he met George Catlin, an American painter who had painted Native Americans on the prairies and who now was on a promotion tour for his book, Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs and Conditions of the North American Indians. Catlin lectured at Egyptian Hall at Piccadilly,

where he also exhibited some of his paintings. In his book Catlin

argued that the culture of the Native Americans was disappearing and

should be recorded before passing into oblivion. Kane found the

argument compelling and decided to similarly document the Canadian

Aboriginal peoples. Kane returned in early 1843 to Mobile, Alabama,

where he set up a studio and worked as a portrait painter until he had

paid back the money borrowed for his voyage to Europe. He returned to

Toronto late 1844 or early 1845 and immediately began preparing for a

trip to the west.

Kane set out on his own on June 17, 1845, travelling along the northern shores of the Great Lakes, visiting first the Saugeen reservation. After weeks of sketching, he reached Sault Ste. Marie between Lake Superior and Lake Huron in summer 1845. He had intended to travel further west, but John Ballenden, an experienced officer of the Hudson's Bay Company stationed

at Sault Ste. Marie, told him of the many difficulties and perils of

travelling alone through the western territories and advised Kane to

attempt such a feat only with the support of the company. After the

Hudson's Bay Company had taken over its competitor, the North West Company of Montreal, in 1821, the whole territory west of the Great Lakes until the Pacific Ocean and the Oregon Country was Hudson's Bay land, a largely uncharted wilderness with about a hundred isolated outposts of the company along the major fur trade routes.

Kane returned to Toronto for the winter, elaborating his field sketches

to oil canvases, and in spring of the next year, he went to the

headquarters of the Hudson's Bay Company at Lachine (today part of Montreal) and asked company governor George Simpson for

support for his travel plans. Simpson was impressed by Kane's artistic

ability, but at the same time worried that Kane might not have the

stamina needed to travel with the fur brigades of the company. He granted Kane passage on company canoes only as far as Lake Winnipeg,

with the promise of full passage if the artist did well until then. At

the same time, he commissioned Kane to do paintings of Indian lifestyle

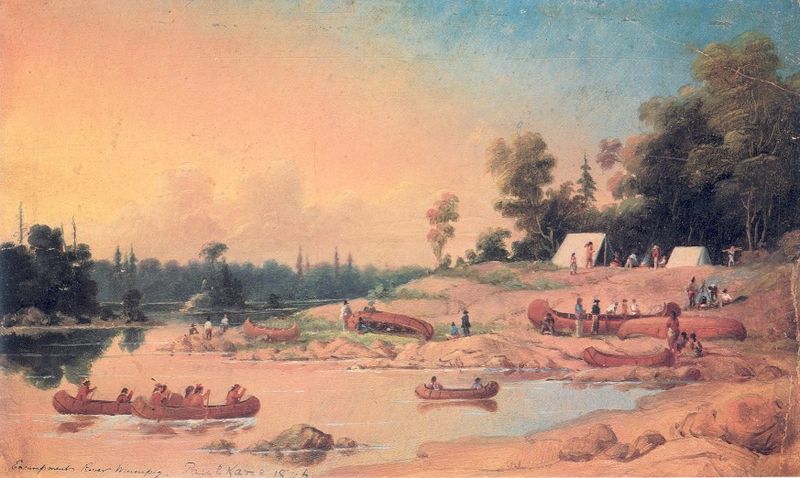

for him, with some very detailed instructions as to the subjects. On May 9, 1846, Kane departed by steamboat from

Toronto with the intent to join a canoe brigade from Lachine at Sault

Ste. Marie. After an overnight stop, he missed the boat, which had left

in the morning earlier than advertised, and he had to race after it by

canoe. Arriving at the Sault, he learned that the canoe brigade had

already left, so he sailed aboard a freight schooner to Fort William on Thunder Bay. He finally caught up with the canoes about 35 miles (56 km) beyond Fort William on the Kaministiquia River on May 24. By June 4 Kane reached Fort Frances, where a pass from Simpson for travelling further was awaiting him. His next stop was the Red River Settlement (near modern-day Winnipeg). There, he embarked on a three-week excursion by horse, joining a large Métis hunting band that went buffalo hunting in Sioux lands in Dakota. On June 26 Kane witnessed and participated in one of the last great buffalo hunts

that within a few decades decimated the animals to near extinction.

Upon his return he continued by canoe and sailing boats by way of Norway House, Grand Rapids, and The Pas up the Saskatchewan River to Fort Carlton. For variety, he continued from there on horseback to Fort Edmonton, witnessing a Cree buffalo pound hunt along the way.

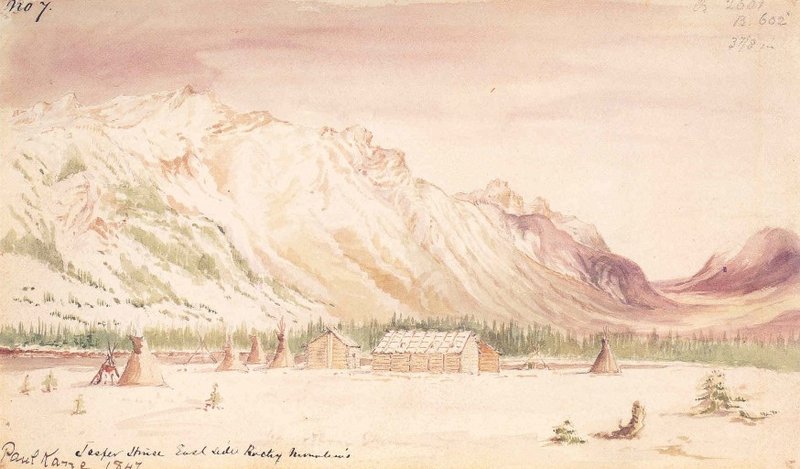

On October 6, 1846, Kane left Edmonton for Fort Assiniboine, where he again embarked with a canoe brigade up the Athabasca River to Jasper's House,

arriving on November 3. Here he joined a large horse troop bound west,

but the party soon had to send the horses back to Jasper's House and

continue on snowshoes, taking only the essentials with them, because Athabasca Pass was

already too deeply snowed in that late in the year. They crossed the

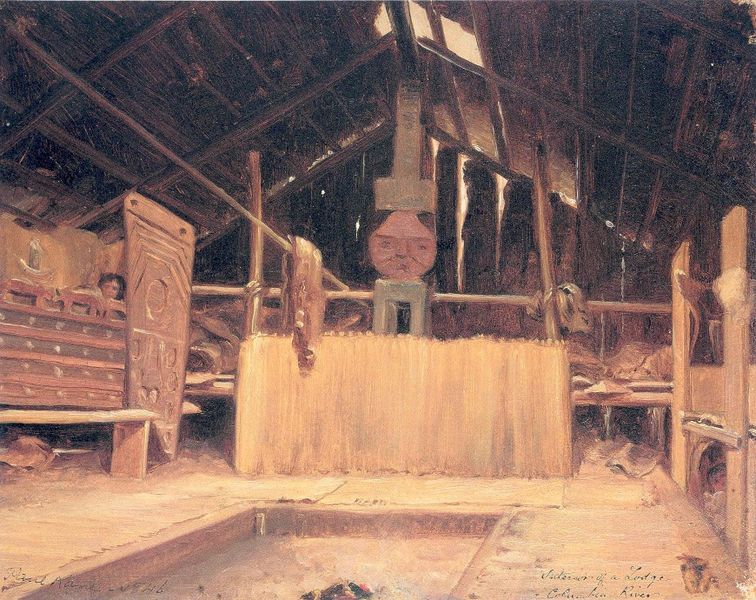

pass on November 12 and three days later joined a canoe brigade that

had been waiting to take them down the Columbia River. Finally, Kane arrived on December 8, 1846, at Fort Vancouver, the main trading post and headquarter of the Hudson's Bay Company in the Oregon Territory. He stayed there over winter, sketching among and studying the Chinookan and other tribes in the vicinity and making several excursions, including a longer one of three weeks through the Willamette Valley. He enjoyed the social life at Fort Vancouver, which at that time was being visited by the British ship Modeste, and became friends with Peter Skene Ogden.

On March 25, 1847, Kane

set out by canoe to Fort Victoria, which had been founded shortly

before to become the new company headquarter, as the operations at Fort

Vancouver were to be wound down and relocated following the conclusion

of the Oregon Treaty of 1846, which fixed the continental border between Canada and the United States west of the Rocky Mountains at the 49th parallel north. Kane went up the Cowlitz River and stayed for a week among the tribes living there in the vicinity of Mount Saint Helens before continuing on horseback to Nisqually (today Tacoma) and then by canoe again to Fort Victoria.

His

painting of Mt. St. Helens in eruption at night in 1847 which is housed

in the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto was the only known image of an

active Cascade volcano until the eruption of Lassen Peak in California

in 1914. Although the scene was somewhat fictionalized, it did

correctly show the active vent on the side of the volcano rather that

the summit. He stayed for two months in that area, traveling and

sketching among the Native Americans on Vancouver Island and around the Juan de Fuca Strait and the Strait of Georgia. He returned to Fort Vancouver in mid-June, from where he departed to return back east on July 1, 1847.

By mid-July Kane had reached Fort Walla Walla, where he made a minor detour to visit the Whitman Mission that a few months later would be the site of the Whitman massacre. He went with Marcus Whitman to visit the Cayuse living in the area and even drew a portrait of Tomahas (Kane

gives the name as "To-ma-kus"), the man who would later be named as

Whitman's murderer. According to Kane's travel report, the relations

between the Cayuse and the settlers at the mission were already

strained by the time of his visit in July. Kane continued with one guide by horseback through the Grande Coulée to Fort Colville, where he stayed for six weeks, sketching and painting the natives who had set up a fishing camp below Kettle Falls at this time of the Salmon run. On September 22, 1847, Kane assumed command of a canoe brigade up the Columbia river and arrived on October 10 at Boat Encampment.

There, the party had to wait for three weeks until a badly delayed

horse trek from Jasper arrived. Then they switched, the horse team

taking over the canoes and going down the Columbia river again and

Kane's group loading their cargo on the horses and taking them back

over Athabasca Pass. They managed to bring all 56 horses safe and

without loss to Jasper's House despite the heavy snow and intense cold.

As the canoes that should have been awaiting them had already left,

they were forced to set out on snowshoes and with a dog sled to Fort

Assiniboine, where they arrived after much hardship and without food

two weeks later. After a few days' rest, they continued to Fort

Edmonton, where they spent the winter. Kane

passed the time at the fort with Buffalo hunting and also sketched

among the Cree living in the vicinity. In January he undertook an

excursion to Fort Pitt, some 200 miles (320 km) down the Saskatchewan River, and then returned to Edmonton. In April he visited Rocky Mountain House, where he wanted to meet Blackfoot. When these did not turn up, he returned to Edmonton. On May 25, 1848, Kane left Fort Edmonton, travelling with a large party of 23 boats and 130 people bound for York Factory, led by John Edward Harriott. On June 1 they met with a large war party of some 1,500 warriors of Blackfoot and other tribes who were planning a raid against the Cree and Assiniboine. On that occasion Kane met the Blackfoot chief Big Snake (Omoxesisixany).

The canoe brigade stayed as briefly as possible and then continued

hastily down the river. On June 18 they arrived at Norway House, where

Kane stayed for a month, waiting for the annual meeting of the chief

factors of the Hudson's Bay Company and the arrival of the party with

which he was bound to travel further. On July 24 he departed with the

party of one Major McKenzie; they travelled along the eastern shore of

Lake Winnipeg to Fort Alexander. From there on Kane followed the same route he had taken two years earlier going west: by the Lake of the Woods, Fort Frances, and Rainy Lake, he travelled by canoe to Fort William and then along the northern shore of Lake Superior until

he reached Sault Ste. Marie on October 1, 1848. From there he returned

by steamboat to Toronto, where he landed on October 13. He noted in his

book on this last leg of his journey: "the greatest hardship that I had

to endure [now] was the difficulty in trying to sleep in a civilized

bed". Kane

now permanently settled in Toronto; he went west only once more when he

was hired by a British party in 1849 as a guide and interpreter, but

they only went as far as the Red River Settlement.

An exhibition of 240 of his sketches in November 1848 in Toronto met

with great success, and a second exhibition in September 1852 showing

eight oil canvases was also received favourably. Politician George William Allan took note of the artist and became his most important patron, commissioning one hundred oil paintings for the price of $20,000 in 1852, which effectively enabled Kane to live a life as a

professional artist. Kane also succeeded in 1851 to convince the Canadian Parliament to commission twelve paintings for the sum of £500, which he delivered in late 1856. In

1853, Kane married Harriet Clench (1823 – 92), the daughter of his former

employer at Cobourg. David Wilson, a contemporary historian of the University of Toronto, reported that she was a skilled painter and writer herself. They had four children, two sons and two daughters. Until

1857, Kane fulfilled his commissions: more than 120 oil canvases for

Allan, the Parliament, and Simpson. His works were shown at the World's Fair at Paris in 1855, where they were reviewed very positively, and some of them were even sent to Buckingham Palace in 1858 for consideration by the Queen.

By that time Kane had also prepared a manuscript derived from his

travel notes and sent to a publishing house in London for publication.

When he did not hear back from them, he travelled to London himself,

and with the support of Simpson got the book published the next year.

It had the title Wanderings

of an Artist among the Indians of North America from Canada to

Vancouver's Island and Oregon through the Hudson's Bay Company's

Territory and Back Again and

was originally published by Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans &

Roberts in London in 1859, beautifully illustrated with many lithographies of

his own sketches and paintings. Kane had dedicated the book to Allan,

which upset Simpson considerably such that he broke off his relations

with Kane. The book was an immediate success and had appeared by 1863

in French, Danish, and German editions. Kane's eyesight was failing rapidly in the 1860s and forced him to abandon painting altogether. Frederick Arthur Verner,

who had been inspired by Kane and himself an artist of "western"

scenes, became an acquaintance and friend. Verner did three portraits

of the ageing Paul Kane, one of which is today also at the Royal

Ontario Museum. Kane died unexpectedly one winter morning in his home,

just having gotten back from his daily walk. He is buried at the St.

James Cemetery in Toronto. The

bulk of Kane's oeuvre is the more than 700 sketches he made during his

two voyages to the west and the more than one hundred oil canvases he

later elaborated from them in his studio in Toronto. Of his early

portraits done at York or Cobourg before his travels, Harper writes,

"[they] are primitive in approach but have a direct appeal and a warm

colouring that make them attractive". The rest are an unknown number of paintings from his time as an itinerant portraitist in the United States, plus a number of copies of classic paintings he did while in Europe. Kane's

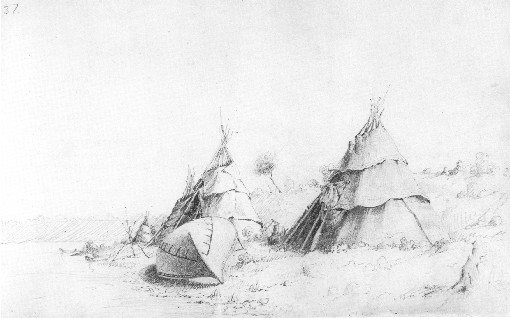

fame rests in his depictions of Native American life. His field

sketches were done in pencil, watercolour, or oil on paper. He also

brought back from his trips a collection of various artefacts such as

masks, pipe stems, and other handicrafts. Together, these formed the

basis for his later studio work. He drew on this pool of impressions

for his large oil canvases, in which he typically combined or

reinterpreted them to create new compositions. The field sketches are a

valuable resource for ethnologists, but the oil paintings, while still

truthful in the individual details of Native American lifestyle, are

often unfaithful to geographic, historic, or ethnographic settings in

their overall compositions. One well-known example of this process is Kane's painting Flathead woman and child, in which he combined a sketch of a Chinookan baby having its head flattened by being strapped to a cradle board with

a later field portrait of a Cowlitz woman living in a different region.

Another example of how Kane elaborated his sketches can be seen in his

painting Indian encampment on Lake Huron, which is based on a sketch taken in summer 1845 during his first trip to Sault Ste. Marie. The painting has a distinct romantic flair

accentuated by the lighting and the dramatic clouds, while the scene of

the camp life depicted is reminiscent of a European idealized rural

peasant scene. Indeed, Kane often created completely fictitious scenes from several sketches for his oil paintings. His oil canvas of Mount St. Helens erupting shows a major and dramatic volcanic eruption,

but from his travel diary and the field sketches he made, it is evident

that the mountain had only been smoking gently at the time of Kane's

visit. (It had, however, erupted three years earlier.) In other

paintings he combined river sketches taken at different times and

places into one painting, creating an artificial landscape that does

not exist in reality. His painting of The Death of Big Snake shows an entirely imaginary scene: the Blackfoot chief Omoxesisixany died only in 1858, more than two years after the painting was completed.

His

models were the classic European paintings, but Kane also had plain

economic reasons for composing his oil paintings in the more mannered

style of the European art tradition. He wanted and had to sell his

paintings to make a living, and he knew his clientele well enough: his

patrons were unlikely to decorate their homes with unadorned copies in

oil of his field sketches; they demanded something more presentable and

closer to the generally Eurocentric expectations of the time. Kane's embellishment is evident in his painting Assiniboine hunting buffalo, one of the twelve done for the parliament. The painting has been criticized for its horses, which look more like Arabians than

any Indian breed. The composition has even been found to be based on

an 1816 engraving from Italy showing two Romans hunting a bull. Already

in 1877, Nicholas Flood Davin commented

on this discrepancy, stating that "the Indian horses are Greek horses,

the hills have much of the colour and form of those of [...] the early

European landscape painters, ..." And Lawrence J. Burpee added

in his introduction to the 1925 reprint of Kane's travel book that the

sketches were "truer interpretations of the wild western life" and had

"in some respects a higher value as art". Twentieth

century and later art theory is less judging than Burpee but agrees

insofar as Kane's field sketches are generally considered more accurate

and authentic. "Kane was the recorder in the field and the artist in

the studio", write Davis and Thacker. Kane

is generally considered a classic and one of the most important

Canadian painters. The eleven surviving paintings done for the

parliament — one painting was lost in the fire on Parliament Hill in 1916 — were transferred in 1955 to the National Gallery of Canada. The large Allan collection was bought by Edmund Boyd Osler in 1903 and donated to the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto in 1912. A collection of 229 sketches was sold by Kane's grandson Paul Kane III for about US$100,000 to the Stark Museum of Art in Orange, Texas, in 1957. A rare painting of his, Scene in the Northwest: Portrait of John Henry Lefroy, showing British surveyor John Henry Lefroy, which had been in possession of the Lefroy family in England, garnered a record price at an auction at Sotheby's in Toronto on February 25, 2002, when Canadian billionaire Kenneth Thomson won the bid at C$5,062,500 including the buyer's premium (US$3,172,567.50 at the time). Thomson subsequently donated the painting as part of his Thomson Collection to the Art Gallery of Ontario. The Glenbow Museum in Calgary has a copy of this painting that is thought to have been done by Kane's wife Harriet Clench. Another auction at Sotheby's on November 22, 2004, for Kane's oil painting Encampment, Winnipeg River failed when bidding stopped at C$1.7 million, less than the expected sale price of C$2–2.5 million. Kane's

travel report, published originally in London in 1859, was a great

success already in its time and has been reprinted several times in the

twentieth century. In 1986 Dawkins criticized Kane's work based mainly

on this travel account, but also on the "European" nature of his oil

paintings, as showing the imperialistic or even racist tendencies of

the artist. This

view remains rather singular among art historians. Kane's travel diary,

which formed the basis for the 1859 book, does not contain any

pejorative judgements. MacLaren reported that Kane's travel notes were

written in a style very different from the published text, such that it

must be considered highly likely that the book was heavily edited by

others or even ghostwritten to turn Kane's notes into a Victorian

travel account, and that it was thus difficult at best to ascribe any

perceived racism to the artist himself. As one of the first Canadian painters who could earn a living from his artwork alone, Kane

prepared the ground for many later artists. His travels inspired others

to similar journeys, and a very direct artistic influence is evident in

the case of F.A. Verner, whose mentor Kane became in his later years. According to Harper, the early Lucius O'Brien was also influenced by Kane's work. Kane's

1848 exhibition of his sketches, which included 155 watercolour and 85

oil on paper paintings, helped establish the genre in the minds of the

public and cleared the way for artists like William Cresswell or Daniel Fowler, who both were able to make a living from their watercolour paintings. Both

his 1848 exhibition of the sketches and the later 1852 show of some of

his oil paintings were great success and lauded by several newspapers. Kane was the most prominent painter in Upper Canada in his time. He

frequently entered his paintings at art exhibitions and won numerous

prizes for his works. He dominated the scene throughout the 1850s, even

to the point where an art jury all but presented their excuses when they did not award

him the prize in the category for historical paintings at the annual

exhibition of the Upper Canada Agricultural Society in 1852. (Kane won

that prize consecutively in all years until 1859, though.) Kane was one of the first, if not the first, tourist to travel across the Canadian west and the Pacific north-west. Through his sketches and paintings, and later also his book, the public at large in Upper and Lower Canada for

the first time caught a glimpse of the peoples and their lifestyles in

this vast and barely known territory. Kane had set out with a sincere

desire to accurately portray his experiences — the landscape, the people,

their tools. Yet it was primarily his embellished studio work that

gained public appeal and made him famous. His idealized oil paintings

and the similarly transformed travel notes that became his book were

both a factor in the establishment and spreading of the perception of

the North American indigenous people as Noble savages, contrary to what the artist had intended. The more truthful field sketches were "rediscovered" and valued by a wider audience only in the twentieth century. In 1937 Kane was declared a National Historic Person, and a plaque to commemorate him was dedicated in Rocky Mountain House in 1952.