<Back to Index>

- Inventor Martin Wiberg, 1826

- Architect Daniel Hudson Burnham, 1846

- Emperor of China Wanli, 1563

PAGE SPONSOR

The Wanli Emperor (4 September 1563 – 18 August 1620) was emperor of China (Ming dynasty) between 1572 and 1620. His era name means "Ten thousand calendars". Born Zhu Yijun, he was the Longqing Emperor's son. His rule of forty eight years was the longest in the Ming dynasty and it witnessed the steady decline of the dynasty. Wanli also saw the arrival of the first Jesuit missionary in Beijing, Matteo Ricci.

Wanli ascended the throne at the age of 9. For the first ten years of his reign, the young emperor was aided by a notable statesman, Zhang Juzheng. Zhang Juzheng directed the path of the country and exercised his skills and power as an able administrator. At the same time, Wanli deeply respected Zhang as a mentor and a valued minister. However as Wanli's reign progressed, different factions within the government began to openly oppose Zhang's policy as well as his powerful position in government and courted Wanli to dismiss Zhang. By 1582, Wanli was a young man of 19 and was tired of the strict routine Zhang still imposed on the emperor since childhood. As such, Wanli was willing to consider dismissing Zhang but before Wanli was able to act, Zhang died in 1582. Overall during these 10 years, the Ming Dynasty's economy and military power prospered in a way not seen since the Yongle Emperor and the "Ren Xuan Rule" from 1402 to 1435. After Zhang's death, Wanli felt that he was free of supervision and reversed many of Zhang's administrative improvements. In 1584, Wanli issued an edict and confiscated all of Zhang's personal wealth and his family members were purged.

After Zhang Juzheng died, Wanli decided to take complete control of the government. During this early part of his rule he demonstrated himself a decent and diligent emperor. Overall, the economy continued to prosper and the country remained powerful. Unlike the 20 years at the end of his rule, Wanli at this time would attend every morning meetings and discuss affairs of state. The first eighteen years of Wanli's reign would be dominated by three wars that he dealt with successfully:

- Defense against the Mongols. In the outer regions, one of the leaders rebelled and allied with the Mongols to attack the Ming. At this time, Wanli sent out Li Chengliang and sons to handle the situation, resulting in overall success.

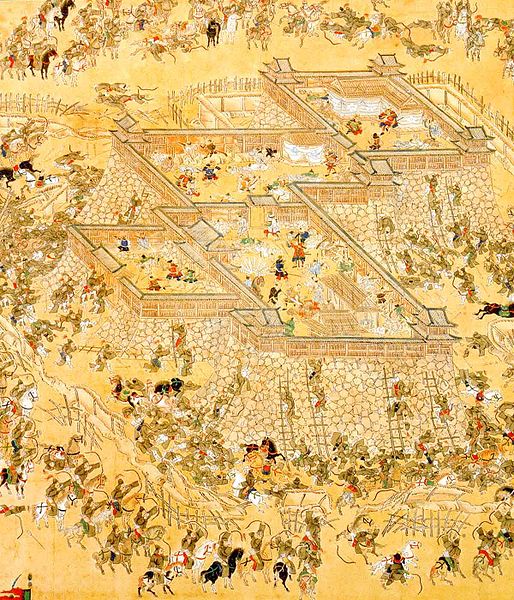

- Toyotomi Hideyoshi of Japan sent 200,000 soldiers in the first expedition to invade Korea. Wanli made three decisions. First, he sent a 3,000 man army to reinforce the Koreans. Second, if Koreans entered Ming territory, he gave them lodging. Third, he instructed the Liaodong area to prepare and be vigilant. In actual combat, the first 2 battles were defeats since Ming troops under Li Rusong were outnumbered and ill-prepared to fight the 200,000-strong Japanese army. Wanli then sent a bigger army of 80,000 men, with more success. This resulted in negotiations that favored the Ming. Two years later, in 1596, Japan once again invaded. However, that same year, Hideyoshi died and the Japanese lost their will to fight. Combined with the leadership of the Korean admiral Yi Sun-sin and the bogging down of Japanese forces in the Korean mainland, the Ming Dynasty defeated the demoralized Japanese army.

- The Yang Yinlong rebellion. At first, Wanli was engaged in war with Japan and sent only 3,000 troops under the command of Yang Guozhu to fight the rebellion. Unfortunately, this army was completely annihilated and Yang Guozhu was killed. When war with Japan ended, Wanli turned his attention to Yang Yinlong, sending Guo Zhizhang and Li Huolong to lead the offensive. In the end, Li Huolong defeated Yang's army and brought him back to the capital.

After

these three successful conflicts, Wanli stopped going to morning

meetings, going into his later reign and his final 20 years on the

throne. During

the latter years of Wanli's reign, he seldom attended state affairs and

for years at a time would refuse to receive his ministers or read any

reports sent to him. Wanli also extorted money from the government, and

ultimately his own people, for his personal enjoyment. One example was

the close attention he paid to the construction of his own tomb, which

took decades to complete. The

Wanli Emperor then became disenchanted with the moralistic attacks and

counterattacks of officials, becoming thoroughly alienated from his

imperial role. Throughout the 1580s and 1590s, Wanli yearned to promote

his third son (Zhu Changxun) by Lady Zheng as crown prince; however, many

of his powerful ministers were opposed to the idea. This led to a clash

between sovereign and ministers that lasted more than 15 years. In

October of 1601 Emperor Wanli eventually gave in and promoted Zhu

Changluo — later Emperor Taichang — as crown prince. Although the

ministers seemed to have overpowered the emperor, Wanli finally

resorted to vengeful tactics of blocking or ignoring the conduct of

administration. For years on end he refused to see his ministers or act

upon memoranda. He refused to make necessary appointments, and

eventually became so obese he was unable even to stand without

assistance. The

whole top echelon of Ming administration became understaffed. In short,

Wanli tried to forget about his imperial responsibilities while

building up personal wealth. Considering the emperor's required role as

the linchpin of the state, this personal rebellion against the

bureaucracy was not only bankruptcy but treason. Finally,

the future threat of the Manchurians developed. The Jurchen area was

eventually conquered by Nurhaci. Nurhaci would go on to create the

Later Jin Empire which would now become an immediate threat. By this

time, after 20 years, the Ming Dynasty army was in steep decline. While

the Jurchens were fewer in number, they were more fierce and powerful. In

the grand battle of Nun Er Chu in 1619, the Ming Dynasty sent out a

force of 200,000 against the Later Jin Empire of 60,000, with Nurhaci

controlling 6 banners and 45,000 as the central attack while Dai Shan

and Huang Taji each controlled 7,500 troops and one banner attacked

from the sides. After 5 days of battle, the Ming Dynasty had casualties

over 100,000, with 70% of their food supply stolen. From this point on,

the Ming Dynasty would lose its advantage to the Jurchens, setting up

the eventual downfall of the Ming Dynasty to the Qing Dynasty.

In

1615 the court was hit by yet another scandal. A man by the name of

Zhang Chai armed with no more than a wooden staff managed to

chase off eunuchs guarding the gates and broke into Ci-Qing palace, then the Crown Prince’s living quarters. Zhang Chai was

eventually subdued and thrown in prison. Initial investigation found

him to be a lunatic, but upon further investigation by a more

conscientious magistrate named Wang Zhicai the man confessed

to being party to a plot instigated by two eunuchs working under Lady

Zheng. According to Zhang Chai’s confession, the two had promised him

rewards for assaulting the Crown Prince, thus implicating the Emperor’s

favorite concubine in an assassination plot. Presented with the

incriminating evidence and the gravity of the accusations, Emperor

Wanli, in an attempt to spare Lady Zheng, personally presided over the

case. He laid the full blame on the two implicated eunuchs who were

executed along with the would-be assassin. Although the case was

quickly hushed up, it did not squelch public discussion and eventually

became known as the "Case of the Palace Assault", one of

three notorious 'mysteries' of the Late Ming Dynasty.

Lady

Zheng (1567? - 1630) was Wanli's favourite concubine who gave birth to

Wanli's third son Zhu Changxun in 1586. Wanli was unable to promote

Lady Zheng as Empress during his reign as well as his son Zhu Changxun

as crown prince due to the opposition of his ministers. Wanli

eventually promoted Lady Zheng as Empress on his deathbed in 1620.

However, this order was never fulfilled by the officials before the

fall of Ming Dynasty. In 1644, since Hongguang Emperor, the first sovereign of the Southern Ming Dynasty,

was a grandson of Lady Zheng, the lady was finally promoted as Empress

by the Southern Ming government, 14 years after her death. The

Wanli emperor’s reign is representative of the decline of the Ming. He

was an unmotivated and avaricious ruler whose reign was plagued with

fiscal woes, military pressures, and angry bureaucrats. He also had

sent eunuch supervisors to provinces to oversee mining operations which

actually became covers for extortion. Discontented with the lack of

morals during this time, a group of scholars and political activists

loyal to Zhu Xi and against Wang Yangming, created the Donglin Movement, a political group who believed in upright morals and tried to influence the government. During

the closing years of Wanli's reign, the Manchu began to conduct raids

on the northern border of the Ming Empire. Their depredations

ultimately led to the overthrow of the Ming dynasty in 1644. It was

said that the fall of the Ming dynasty was not a result of the Chongzhen Emperor's rule but instead due to Wanli's gross mismanagement. The Wanli Emperor died in 1620 and was buried in Dingling located on the outskirts of Beijing.

His tomb is one of the biggest in the vicinity and one of only two that

are open to the public. In 1997 China's Ministry of Public Security

published a book on the history of drug abuse. It stated that the Wanli

emperor's remains had been examined in 1958 and found to contain

morphine residues at levels which indicate that he had been a heavy and

habitual user of opium. On

the other hand, Emperor Wanli's contribution to the defense of the

Chosun Dynasty in Korea against the Japanese invasion has endeared him

to Koreans over the centuries. In the late 1990s, Koreans still paid

respect to Wanli. In

many ways, he was similar to other Chinese emperors who were initially

successful, but whose subsequent poor rule caused the eventual demise

of their dynasties, such as Emperor Xuanzong of Tang and the Qianlong Emperor of the Qing Dynasty.