<Back to Index>

- Classical Scholar Johann Friedrich Gronovius, 1611

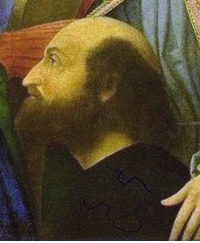

- Poet Ludovico Ariosto, 1474

- General Louis de Bourbon, Prince of Condé, 1621

PAGE SPONSOR

Ludovico Ariosto (8 September 1474 – 6 July 1533) was an Italian poet. He is best known as the author of the romance epic Orlando Furioso (1516). The poem, a continuation of Matteo Maria Boiardo's Orlando Innamorato, describes the adventures of Charlemagne, Orlando, and the Franks as they battle against the Saracens with diversions into many side plots. Ariosto composed the poem in the ottava rima rhyme scheme and introduced narratorial commentary throughout the work.

Ariosto was born in Reggio Emilia,

where his father Niccolò Ariosto was commander of the citadel.

He was the oldest of ten children and was seen as the successor to the

patriarchal position of his family. From his earliest years, Ludovico

was very interested in poetry, but he was obliged by his father to

study law. After five years of law, Ariosto was allowed to read classics under Gregorio da Spoleto. Ariosto's studies of Greek and Latin literature were cut short by Spoleto's move to France to tutor Francesco Sforza. Shortly after, Ariosto's father died. After

the death of Ariosto's father, Ludovico was compelled to forgo his

literary occupations and take care of his family, whose affairs were in

disarray. Despite his family obligations, Ariosto managed to write some

comedies in prose as well as lyrical pieces. Some of these attracted

the notice of Cardinal Ippolito d'Este,

who took the young poet under his patronage and appointed him one of

the gentlemen of his household. Este compensated Ariosto poorly for his

efforts. The only reward he gave the poet for Orlando Furioso,

a piece dedicated to him, was the question, "Where did you find so many

stories, Master Ludovic?" The poet himself tells us that the cardinal

was ungrateful, that he deplored the time which he spent under his

yoke, and adds, that if he received some niggardly pension, it was not

to reward him for his poetry, which the prelate despised, but to make

some just compensation for the poet's running like a messenger, with

the work of his life yet to accomplish, at his eminence's pleasure. Nor

was even this miserable pittance regularly paid during the period that

the poet enjoyed it. The cardinal went to Hungary in

1518, and wished Ariosto to accompany him. The poet excused himself,

pleading ill health, his love of study, the care of his private affairs

and the age of his mother, whom it would have been disgraceful to

leave. His excuses were not well received, and even an interview was

denied him. Ariosto then boldly said, that had his eminence thought to

have bought a slave by assigning him the scanty pension of seventy-five

crowns a year, he was mistaken and might withdraw his boon — which it

seems the cardinal did. The cardinal's brother, Alfonso, duke of Ferrara,

now took the poet under his patronage. This was but an act of simple

justice, Ariosto having already distinguished himself as a diplomat,

chiefly on the occasion of two visits to Rome as ambassador to Pope Julius II.

The fatigue of one of these hurried journeys brought on a complaint

from which he never recovered, and on his second mission he was nearly

killed by order of the pope, who happened at the time to be much

incensed against the duke of Ferrara. On

account of the war, his salary of only 84 crowns a year was suspended,

and it was withdrawn altogether after the peace. Because of this,

Ariosto asked the duke either to provide for him, or to allow him to

seek employment elsewhere. He was appointed to the province of Garfagnana,

then without a governor, situated on the wildest heights of the

Apennines, an appointment he held for three years. The place was no

sinecure. The province was distracted by factions and banditi,

the governor had not the requisite means to enforce his authority and

the duke did little to support his minister. Yet it is said that

Ariosto's government satisfied both the sovereign and the people given

over to his care; indeed, there is a story about a time when he was

walking alone and fell into the company of a group of banditi, the chief of which, on discovering that his captive was the author of Orlando Furioso, humbly apologized for not having immediately shown him the respect which was due to his rank. In 1508 his play Cassaria appeared, and the next year I Suppositi. In 1516, the first version of the Orlando Furioso in forty cantos, was published at Ferrara. The third and final version of the Orlando Furioso, in forty-six cantos, appeared on September 8, 1532.

Throughout

Ariosto's writing are narratorial comments dubbed by Dr. Daniel Javich

as "Cantus Interruptus". These sections are short breaks in the text in

which the narrator destroys the fourth wall and talks directly to the

audience. Whether this is for comedic reasons or is just a continuation

of the oral tradition, Ariosto uses it throughout his works. For

example, in Canto II, stanza 30, of Orlando Furioso, the narrator says: Some have attributed this piece of metafiction as one component of the "Sorriso ariostesco" or Ariosto smile, the wry sense of humor that Ariosto adds to the text. In explaining this humor, Thomas Greene, in his critical work Descent from Heaven,

says "the two persistent qualities of Ariosto's language are first,

serenity - the evenness and self-contented assurance with which it

urbanely flows, and second, brilliance - the Mediterranean glitter and

sheen which neither dazzle nor obscure but confer on every object its

precise outline and glinting surface. Only occasionally can Ariosto's

language truly be said to be witty, but its lightness and agility

create a surface which conveys a witty effect. Too much wit could

destroy even the finest poem, but Ariosto's graceful brio is at least as difficult and for narrative purposes more satisfying".