<Back to Index>

- Physicist Jean Bernard Léon Foucault, 1819

- Composer Francesca Caccini, 1587

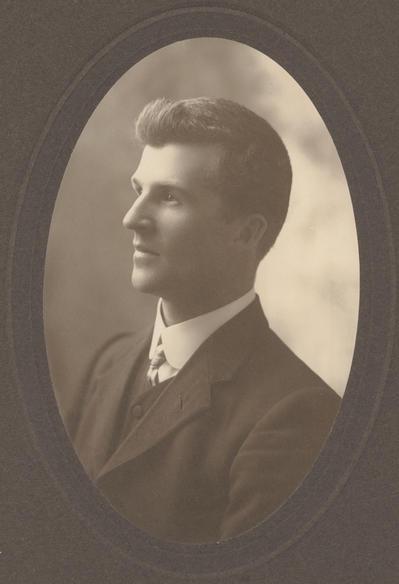

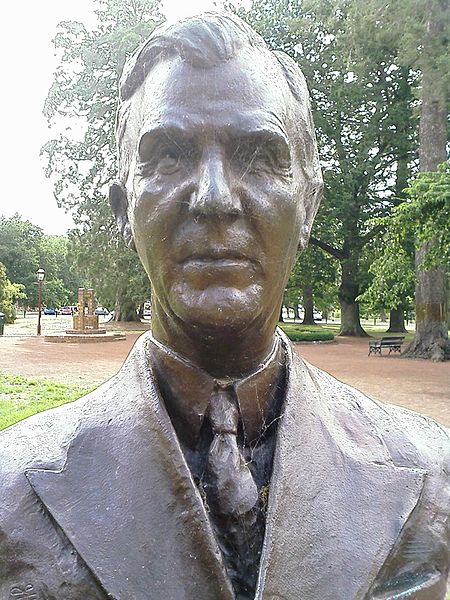

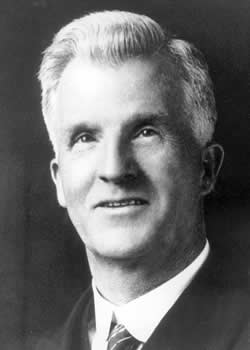

- 9th Prime Minister of Australia James Henry Scullin, 1876

PAGE SPONSOR

James Henry Scullin (18 September 1876 – 28 January 1953) was an Australian Labor politician and the ninth Prime Minister of Australia. Two days after he was sworn in as Prime Minister, the Wall Street Crash of 1929 occurred, marking the beginning of the Great Depression and subsequent Great Depression in Australia.

Scullin was born in the small town of Trawalla in western Victoria, the son of John Scullin, a railway worker, and Ann (née Logan), both of Irish Catholic descent from Derry. He was educated at state primary schools and then worked as a grocer in Ballarat while studying at night school and privately in public libraries and honing his public speaking skills in local debating clubs.

He joined the Labor Party in 1903 and became an organiser for the Australian Workers' Union. In 1913, he became editor of a Labor newspaper in Ballarat, the Evening Echo. He was a devout Roman Catholic, a non-drinker and a non-smoker all his life. Scullin stood for the House of Representatives seat of Ballaarat in 1906 against Alfred Deakin, but lost. In 1910 he was elected to the House for the country seat of Corangamite, but he was defeated in 1913 and went back to editing the Evening Echo. He established a reputation as one of Labor's leading public speakers and experts on finance, and was a strong opponent of conscription. After World War I he came close to outright pacifism. In 1922 he won a by-election for the safe Labor seat of Yarra in inner Melbourne, and in 1928 he was elected Labor leader following the resignation of Matthew Charlton. In 1929 the conservative government of Stanley Bruce fell

when its industrial relations bill was defeated in the House of

Representatives. In the subsequent elections Scullin campaigned as the

defender of the industrial arbitration system and won a landslide

victory, becoming Australia's first Roman Catholic Prime Minister. As

this election was only for the House of Representatives the conservatives retained control of the Senate. Two days after Scullin took office on 22 October 1929, the New York stock market crashed and Australia became caught up in the worldwide Great Depression. The

Depression hit Australia hard in 1930, with the collapse in export

markets for Australia's agricultural products causing mass

unemployment. Scullin's government, guided by orthodox economic advice,

was unable to cope, and the Labor Party was rent by internal conflict

over how to respond. The Treasurer (finance minister), Ted Theodore, was an early advocate of Keynesian economic ideas, and advocated deficit financing as a means of reflating the economy, but his Cabinet colleagues Joseph Lyons and James Fenton strongly supported traditional deflationary economic policies. In

June 1930 the government suffered a heavy loss when Theodore was forced

to resign after he was criticised by a Royal Commission inquiring into

a scandal (the Mungana affair) dating back to Theodore's time as Premier of Queensland. Scullin took over the Treasury portfolio. Matters were made worse by Scullin's decision to travel to London to seek an emergency loan and to attend the Imperial Conference. While in London, Scullin succeeded in gaining loans for Australia at reduced interest. He also succeeded in having King George V appoint Sir Isaac Isaacs as the first Australian-born Governor - General,

despite the King's reluctance and the strong objections of both the

British establishment and the conservative opposition in Australia, who

attacked the appointment as tantamount to republicanism. With

Scullin out of the country for the whole second half of 1930, Fenton

(as acting Prime Minister) and Lyons (as acting Treasurer) were left in

charge. They insisted on pursuing deflationary policies, arousing great

opposition in the Labor caucus. In regular contact with Fenton and

Lyons in London through the awkward means of cables, Scullin felt he

had no choice but to agree to the recommendations of advisers from the Bank of England,

supported by Lyons and Fenton, that government spending be heavily cut,

despite the suffering this caused. These decisions led to furious

infighting in the government and destroyed any semblance of party unity. During

1931 the Scullin government disintegrated. In January, Scullin returned

to Australia and decided to reinstate Theodore as Treasurer. Lyons,

Fenton and their supporters resigned from the ministry in protest and

soon joined up with the Nationalist Opposition to form the United Australia Party, led by Lyons. Meanwhile the Labor Premier of New South Wales, Jack Lang was

campaigning for economic policies much more left-wing than Theodore's,

calling for Australia to repudiate its foreign debt and take other radical measures. In March, Lang's supporters in the federal Parliament had split from the Labor Party, forming a "Lang Labor"

group, which, combined with the defections of Lyons and his supporters,

had deprived the Scullin Government of its majority in the House of

Representatives. However, the Government limped on until November, due

to the reluctance of the Langite MPs to vote it down. Finally, however,

on 25 November 1931, the Langite MPs, attacking the government with

accusations of impropriety, voted with the Opposition to pass a motion of no confidence, forcing an early election. Labor was defeated in a massive landslide in 1931.

The official Labor Party, which had won 46 seats out of 75 in the House

of Representatives in 1929, was reduced to a mere 14 (Lang Labor won

another 4), and Lyons became Prime Minister. Scullin felt traumatised by the experience of presiding over such a disastrous period, but stayed on as Labor leader. After

losing another election in 1934, he resigned the leadership. He

remained in Parliament and became a trusted adviser to later Labor Prime Ministers John Curtin and Ben Chifley. He retired in 1949 and died in Melbourne in 1953 at the age of 76. Historians have judged him as a conscientious, well-meaning politician who was simply overwhelmed by events. As Leader of the Opposition, Scullin had been a vocal opponent of the cost of The Lodge, the official residence of the Prime Minister. True to his word, he and his wife lived at the Hotel Canberra during parliamentary sessions, and at their home in Melbourne at other times. On November 11, 1907, in Ballarat, Victoria, he married Sarah Maria McNamara (1880 – 1962). The marriage was childless. While

no specific record of Sarah Scullin’s work as prime ministerial wife is

available, a trace of her official, ceremonial and social duties can be

gleaned from newspaper accounts of Scullin’s daily appointments. For

instance, a three-day visit to Sydney soon after taking office involved

Sarah Scullin’s participation in a wreath laying ceremony at the

Cenotaph, the silver jubilee banquet of the Labor women’s organising

committee at Trades Hall in Sussex Street, and a lunch hosted by the

New South Wales Institute of Journalists. Scullin, Australian Capital Territory, a suburb of Canberra, is named after him, as is the Division of Scullin, a House of Representatives electorate. In 1975 he was honoured on a postage stamp bearing his portrait issued by Australia Post.