<Back to Index>

- Mathematician William Wallace, 1768

- Painter František Kupka, 1871

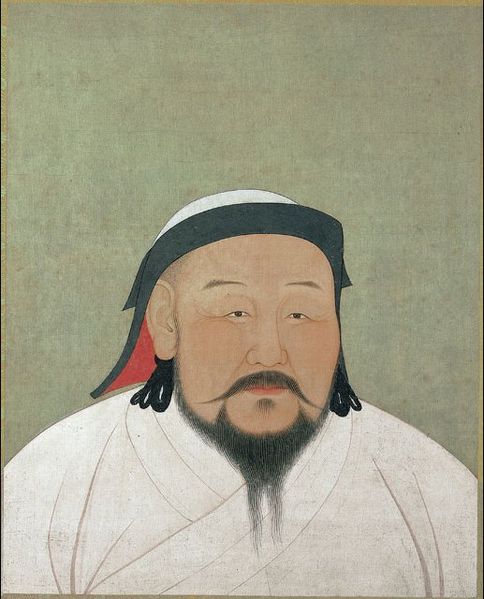

- Great Khan of the Mongol Empire Kublai, 1215

PAGE SPONSOR

Kublai (or Khubilai) Khan (Mongolian: Хубилай хаан; Chinese: 忽必烈; pinyin:Hūbìliè) (September 23, 1215 – February 18, 1294) was the fifth Great Khan of the Mongol Empire from 1260 to 1294 and the founder of the Yuan Dynasty in East Asia. As the second son of Tolui and Sorghaghtani Beki and a grandson of Genghis Khan, he claimed the title of Khagan of the Ikh Mongol Uls (Mongol Empire) in 1260 after the death of his older brother Möngke in the previous year, though his younger brother Ariq Böke was also given this title in the Mongolian capital at Karakorum. He eventually won the battle against Ariq Böke in 1264, and the succession war essentially marked the beginning of disunity in the empire. Kublai's real power was limited to China and Mongolia after the victory over Ariq Böke, though his influence still remained in the Ilkhanate, and to a lesser degree, in the Golden Horde, in the western parts of the Mongol Empire. His realm reached from the Pacific to the Urals, from Siberia to Afghanistan – one fifth of the world's inhabited land area.

In 1271, Kublai established the Yuan Dynasty, which at that time ruled over present-day Mongolia, Tibet, Eastern Turkestan, North China, much of Western China, and some adjacent areas, and assumed the role of Emperor of China. By 1279, the Yuan forces had successfully annihilated the last resistance of the Southern Song Dynasty,

and Kublai thus became the first non-Chinese Emperor who conquered all

China. He was the only Mongol khan after 1260 to win new great

conquests. As the Mongol Emperor who welcomed Marco Polo to China, Kublai Khan became a legend in Europe. Kublai (b. 23 Sep. 1215) was the second son of Tolui and Sorghaghtani Beki. As his grandfather Genghis Khan advised, Sorghaghtani chose as her son's nurse a Buddhist Tangut woman whom Kublai later honored highly. On his way back home after the conquest of Khwarizmian Empire, Genghis Khan performed the ceremony on his grandsons Mongke and Kublai after their first hunting in 1224 near the Ili River. Kublai was nine years old and with his eldest brother killed a rabbit and an antelope. His grandfather smeared fat from killed animals onto Kublai's middle finger following the Mongol tradition. After the Mongol - Jin War, in 1236, Ogedei gave Hebei Province

(attached with 80,000 households) to the family of Tolui who died in

1232. Kublai received an estate of his own and 10,000 households there.

Because he was inexperienced, Kublai allowed local officials free rein.

Corruption amongst his officials and aggressive taxation caused the

flight of large numbers of Chinese peasants, which in turn led to a

decline in tax revenues. Kublai quickly came to his appanage in

Hebei and ordered reforms. Sorghaghtani sent new officials to help him

and tax laws were revised. Thanks to those efforts, people returned to

their old homes. The

most prominent, and arguably influential component of Kublai Khan's

early life was his study and strong attraction to contemporary Chinese culture. Kublai invited Haiyun, the leading Buddhist monk in North China, to his ordo in Mongolia. When he met Haiyun in Karakorum in 1242, Kublai asked him about the philosophy of Buddhism. Haiyun named Kublai's son, Zhenjin (True Gold in Chinese language), who was born in 1243. Haiyun also introduced Kublai the former Taoist and now Buddhist monk, Liu Bingzhong. Liu was a painter, calligrapher, poet and mathematician, and became Kublai's advisor when Haiyun returned to run his temple in modern Beijing. Kublai soon added the Shanxi scholar

Zhao Bi to his entourage. Kublai employed other nationalities as well, for he was keen to balance local and imperial interests, Mongol and Turk. In 1251, his eldest brother Möngke became Khan of the Mongol Empire, and Khwarizmian Mahmud Yalavach and Kublai were sent to China. Kublai received the viceroyalty over North China and moved his ordo to central Inner Mongolia. During his years as viceroy, Kublai managed his territory well, boosting the agricultural output of Henan and increasing social welfare spendings after receiving Xi'an.

These acts received great acclaim from the Chinese warlords and were

essential to the building of the Yuan Dynasty. In 1252 Kublai

criticized Mahmud Yalavach, who never stood high in the valuation of

his Chinese associates, over his cavalier execution of suspects during

a judicial view

and Zhao Bi attacked him for his presumptuous attitude toward the

throne. With Chinese Confucian trained officials' resistance, Mongke

dismissed Mahmud Yalavach. In 1253, Kublai was ordered to attack Yunnan, and he asked the Kingdom of Dali to submit. The ruling family, Gao, resisted and murdered Mongol envoys. The Mongols divided their forces into three. One wing rode eastward into the Sichuan basin. The second column under Subotai's son Uryankhadai took a difficult way into the mountains of western Sichuan. Kublai

himself headed south over the grasslands, meeting up with the first

column. While Uryankhadai galloping in along the lakeside from the

north, Kublai took the capital city of Dali and

spared the residents despite the slaying of his ambassadors. The

Mongols appointed King Duan Xingzhi as local ruler and stationed a

pacification commissioner there. After Kublai's departure, unrest broke out among the Black jang. By 1256, Uryankhadai had completely pacified Yunnan. Kublai was attracted by the abilities of Tibetan monks as healers. In 1253 he made Phagspa lama of the Sakya order member of his entourage. Phagspa bestowed on Kublai and his wife, Chabi (Chabui), a Tantric Buddhist initiation. Kublai appointed Uyghur Lian

Xixian (1231 – 1280) to head his Pacification Commission in 1254. Some

officials who were jealous of Kublai's success muttered that he was

getting above himself, dreaming of his own empire by rivalling Mongke's

capital Karakorum (Хархорум).

The Great Khan Mongke sent 2 tax inspectors, Alamdar (Ariq Böke's

close friend and governor in North China) and Liu Taiping, to audit

Kublai's officials in 1257. They found fault, listed 142 breaches of

regulations, accused Chinese officials, even had some executed and

Kublai's new Pacification Commission was abolished. Kublai

sent a two-man embassy with his wives and then in person appealed to

Mongke as brother to brother. Mongke publicly forgave his younger

brother and reconciled with him. The Taoists had exploited their wealth and status by seizing Buddhist temples. Mongke demanded that the Taoists cease their denigration of Buddhism repeatedly and ordered Kublai to end the clerical strife between the Taoists and Buddhists in his territory. Kublai called a conference of Taoist and Buddhist leaders in early 1258. At

the conference, the Taoist claim was officially declared refuted and

Kublai forcibly converted their 237 temples to Buddhism and destroyed

all copies of the fraudulent texts. In 1258, Möngke put Kublai in command of the Eastern Army and summoned him to assist with an attack on Sichuan.

Already suffering from gout, Kublai was allowed to stay, however, he

moved to assist his brother, Mongke. Before Kublai could arrive in

1259, word reached him that Möngke had died. Kublai decided to

keep the death of his brother a secret and continued to attack Wuhan, near Yangtze. While his force was besieging Wuchang, Subotai's son Uryankhadai joined him. The Song minister Jia Sidao made a secret approach to Kublai to propose terms and asked whether the Song paid an annual tribute of 200,000 taels of silver and 200,000 bolts of silk, in exchange for the Mongols agreeing that the Yangtze should be the frontier between the states. Kublai

first declined but reached a peace agreement with Jia Sidao and

returned north to the Mongolian plains because he learned in a message

from his wife that Ariq Böke had been raising troops. He soon received news that his younger brother Ariq Böke had held a kurultai at

the Mongolian imperial capital of Karakorum and was pronounced Great

Khan by Mongke's old officials. Most of Genghis Khan's descendants

favored Ariq Böke as Great Khan; however, his two brothers Kublai

and Hulegu were in opposition. Kublai's Chinese staff encouraged him to

ascend the throne, and virtually all the senior princes in North China

and Manchuria supported his candidacy. Upon

returning to his own territories, Kublai summoned a kurultai of his

own. Only a small number of the royal family supported Kublai's claims

to the title, though the small number of attendees, included

representatives of all the Borjigin lines except that of Jochi, still proclaimed him Great Khan, on April 15, 1260, despite his younger brother Ariq Böke's apparently legal claim. This

subsequently led to warfare between Kublai and his younger brother Ariq

Böke, which resulted in the eventual destruction of the Mongolian

capital at Karakorum. In Shaanxi and

Sichuan, Mongke's army supported Ariq Böke. Kublai dispatched Lian

Xixian to Shaanxi and Sichuan where they executed Ariq Böke's

civil administrator Liu Taiping and won over several wavering generals. To secure his southern front, Kublai did try for a diplomatic solution by sending envoys to Hangzhou, but Jia broke his promise and arrested them. Kublai sent Abishqa as new khan to the Chagatai Khanate. Ariq Böke captured Abishqa, two other princes and 100 men and had his own man, Alghu, crowned khan of Chagatai's

territory. Then came the first armed clash between Ariq Böke and

Kublai. Ariq Böke was lost and his commander Alamdar was killed at

the battle. In revenge, Ariq Böke had Abishqa executed. Kublai

closed the food supply to Karakorum with the support of his cousin Khadan, son of Ogedei Khan.

Karakorum fell quickly to Kublai's large army, but in 1261 Ariq

Böke temporarily took it again after Kublai's departure. During

the war with Ariq Böke, Yizhou governor Li Tan revolted against

Mongol rule in February 1262. Hearing this, Kublai ordered his

Chancellor Shi Tianze and

Shi Shu to take the offensive against Li Tan. These two armies crushed Li

Tan's revolt in a few months and Li Tan was executed. Execution was also the fate of Wang Wentong,

who was the father-in-law of Li Tan and had been appointed the Chief

Administrator of the Zhongshusheng ("Department of Central Governing")

early in Kublai's reign and became one of the most trusted Han Chinese

officials of Kublai. This incident instilled in him a strong distrust

of ethnic Hans. After he became emperor, Kublai began to ban the titles of and tithes to Han Chinese warlords. The Chagatayid Khan Alghu declared his allegiance to Kublai Khan and defeated a punitive expedition sent by Ariq Böke against him in 1262. Ilkhan Hulegu also sided with Kublai and criticized Ariq Böke. Ariq Böke surrendered to Kublai at Xanadu on August 21, 1264. The rulers of western khanates acknowledged the reality of Kublai's victory and rule in Mongolia. When

Kublai summoned them to organize another kurultai, Alghu Khan demanded

security for his illegal position from Kublai in return. Despite

tensions between them, both Hulegu and Berke, khan of the Ulus of Jochi (Golden Horde), accepted Kublai's invitation at first. However,

they soon declined to attend the new kurultai. Although, Kublai

pardoned his younger brother, he executed Ariq Böke's chief

supporters. Suspicious deaths of 3 Jochid princes in Hulegu's service, the sack of Baghdad,

and unequal distribution of war booties strained the Ilkhanate's

relations with the Golden Horde. In 1262, Hulegu's complete purge of

the Jochid troops, and support for Kublai in his conflict with Ariq

Böke brought open war with the Golden Horde. Khagan Kublai

reinforced Hulegu with 30,000 young Mongols in order to stabilize the

political crises in western regions of the Mongol Empire. As soon as Hulegu died on 8 February 1264, Berke marched to cross near Tiflis to conquer the Ilkhanate, but he died on the way. Within a few months of these deaths, Alghu Khan of the Chagatai Khanate died

too. In the new official version of the family history, Kublai Khan

refused to write Berke's name as the khan of the Golden Horde for his

support to Ariq Böke and wars with Hulegu, however, Jochi's family

was fully recognized as legitimate family members. Kublai named Abagha as the new Ilkhan and nominated Batu's grandson Mongke Temur for the throne of Sarai, the capital of the Golden Horde. The Kublaids in the east retained suzerainty over the Ilkhans (obedient khans) until the end of its regime. Kublai also sent his protege Baraq to overthrow the court of Oirat Orghana, the empress of the Chagatai Khanate, who put her young son Mubarak Shah on the throne in 1265, without Kublai's permission after her husband's death. Ogedeid prince Kaidu declined

to personally come to the court of Kublai. Kublai instigated Baraq to

attack him. Baraq began to expand his realm northward, fighting Kaidu

and the Jochids after he seized power in 1266. He also pushed out Great

Khan's overseer from Tarim basin. When Kaidu and Mongke Timur defeated him together, Baraq joined an alliance with the House of Ogedei and

the Golden Horde against Kublai in the east and Abagha in the west. But

smart Mongke Temur stayed out of any direct military expedition against

the Empire of the Great Khan. The armies of Mongol Persia defeated Baraq's invading forces in 1269.

When Baraq died the next year, Kaidu took control over the Chagatai

Khanate. Meanwhile, Kublai stabilized the Mongol rule in Korea by mobilizing for another Mongol invasion after he appointed Wonjong (r. 1260 - 1274) as the new Goryeo king in 1259 in Kanghwa. He forced two

rulers of the Golden Horde and the Ilkhanate to call a truce with each

other in 1270 despite the Golden Horde's interests in the Middle East

and Caucasia. He called 2 Iraqi siege engineers from the Ilkhanate in order to destroy the fortresses of the Song China. After the fall of Xiangyang in 1273, Kublai's commanders, Aju and Liu Zheng, proposed to him a final campaign of annihilation against the Song Dynasty, and Kublai made Bayan the supreme commander. Therefore,

Kublai ordered Mongke Temur to revise the second census of the Golden

Horde to provide sources and men for his conquest of China. The census took place in all parts of the Golden Horde, including Smolensk and Vitebsk in 1274 - 75. The Khans also sent Nogai to Balkan to strengthen Mongol influence there. As

the Great Khan Kublai renamed the Mongol regime in China Dai Yuan in

1271, he sought to sinicize his image as Emperor of China in order to

win control of the millions of Chinese people. When he moved his

headquarters to Khanbalic or Dadu at modern Beijing, there was an uprising in the old capital Karakorum that he barely

staunched. His actions were condemned by traditionalists and his

critics still accused him of being too closely tied to Chinese culture.

They sent a message to him: "The old customs of our Empire are not

those of the Chinese laws… What will happen to the old customs?". Even

Kaidu attracted the other elites of Mongol Khanates, declaring himself

to be a legitimate heir to the throne instead of Kublai who had turned

away from the ways of Genghis Khan. Defections from Kublai's Dynasty swelled the Ogedeids' forces. The

Song imperial family surrendered to the Yuan in 1276, making the

Mongols the first non-Chinese people to conquer all of China. Three years later, Yuan marines crushed the last of the Song loyalists. The Song Empress Dowager and her grandson, Zhao Xian,

were then settled in Khanbalic where they were given tax-free property.

Kublai's wife Chabi took a personal interest in their well-being. However, Kublai had Zhao sent away to become a monk to Zhangye later. Kublai succeeded in building a powerful Empire, creating an academy, offices, trade ports and canals and sponsoring arts and science. The record of the Mongols lists 20,166 public schools created during his reign. Achieving

actual or nominal dominion over much of Eurasia, and having seen his

successful conquest of China, Kublai was in a position to look beyond

China. However, Kublai's costly invasions of Burma, Annam, Sakhalin and Champa secured only the vassal status of those countries. Mongol invasions of Japan (1274 and 1280) and Java (1293) failed. At the same time his nephew Ilkhan Abagha tried to form a grand alliance of the Mongols and the Western Europeans to defeat the Mamluks in Syria and

North Africa that constantly invaded the Mongol dominions. Abagha and

his uncle Kublai focused mostly on foreign alliances, and opened trade

routes. Khagan Kublai dined with a large court every day, and met with

many ambassadors, foreign merchants, and even offered to convert to

Christianity if this religion was proved to be correct by 100 priests. Kublai's son Nomukhan and generals occupied Almaliq from

1266 - 76. In 1277, a group of Genghisid princes under Mongke's son

Shiregi rebelled, kidnapping Kublai's two sons and his general Antong.

The rebels handed them over to Kaidu and Mongke Temur. The latter was

still allied with Kaidu who fashioned an alliance with him in 1269,

although, he promised Kublai Khan his military support to protect him

from the Ogedeids. Great Khan's armies suppressed the rebellion and strengthened the Yuan garrisons in Mongolia and Uighurstan. However, Kaidu took control over Almaliq. In 1279 - 80, Kublai decreed death for those who performed Islamic - Jewish slaughtering of cattles, which offended Mongolian custom. When the Muslim Ahmad Teguder seized the throne of the Ilkhanate in 1282, attempting to make peace with the Mamluks, Abagha's old Mongols under prince Arghun appealed

to the Great Khan. After the execution of Ahmad, Kublai confirmed

Arghun's coronation and awarded his commander in chief Buqa who

helped his master the title of chingsang. However, a large Muslim

community was created in China under Kublai's rule and the Muslims

still shared power with the Mongols within his administration. In spite

of his lack of direct control over the western khanates and the Mongol

princes’ rebellions, it seems Kublai could intervene in their affairs

because Abagha's son Arghun wrote that Great Khan Kublai ordered him to

conquer Egypt in his letter to the Pope Nicolas IV. Kublai's niece Kelmish, who was married a Khunggirat general

of the Golden Horde, was powerful enough to have Kublai's sons Nomuqan

and Kokhchu returned. The court of the Golden Horde sent them back as a

peace overture to the Yuan Dynasty in 1282 and induced Kaidu to release

the general of Kublai. Konchi, khan of White Horde, established friendly relations with the Yuan and the Ilkhanate, receiving luxury gifts and grain from Kublai as reward. Despite

political disagreement between contending branches of the family over

the office of Khagan, the economic and commercial system which trumped

their squabbles continued. Despite Kublai restricting the functions of kheshig (khan's bodyguard), he created a new imperial bodyguard, at first entirely Chinese in composition but later strengthened with Kipchak, Alan (Asud), and Russian units. Once

his own kheshig was organized in 1263, Kublai put three of the four

shifts of the kheshig under descendants of Genghis Khan's four steeds,

Borokhula, Boorchu and Muqali. Kublai Khan began the practice of having the four great aristocrats in his kheshig sign all jarliqs (decree), a practice that spread to all other Mongol khanates. Both

Mongol and Chinese units were organized according to the same decimal

organization that Genghis Khan used. The Mongols eagerly adopted new artillery and technologies. While Kublai's younger brother Hulegu used 1,000 Chinese mangonel operators under Barga Mongol Ambaghai, he brought siege engineers, Ismail and Al al-Din, from Iraq and Iran. The world's earliest known cannon, dated 1282, was found in Mongol held Manchuria. Kublai

and his generals avoided total destruction of South China for economic

benefits. Effective assimilation of Chinese naval techniques allowed

the Yuan army to quickly conquer the Song and advance beyond the seas. Diplomatically and militarily, Kublai's foreign policy, as the previous Mongolian Khagans, was imperialistic. Kublai Khan made Goryeo (Korea) a tributary vassal in 1260. The Yuan helped Wonjong stabilize his control over Korea in 1271. After the Mongol invasion in 1273, the Goryeo was fully integrated in the Yuan realm. The

Goryeo in Korea became a Mongol military base and several myriarchy

commands were established there. The court of the Goryeo supplied Korean troops and ocean naval force

for the Mongol campaigns. Despite the opposition of his

Confucian trained Chinese advisers, Kublai decided to invade Japan, Burma, Vietnam and Java, following his Mongol officials. These costly conquests along with the introduction of paper currency, caused inflation. From 1273 to 1276 war against the Song Dynasty and Japan made emissions

of paper currency explode from 110,000 ding to 1,420,000 ding. Dr. Kenzo Hayashida, a marine archaeologist, headed the investigation that discovered the wreckage of the second invasion fleet off the western coast of Takashima.

His team's findings strongly indicate that Kublai Khan rushed to invade

Japan and attempted to construct his enormous fleet in only one year (a

task that should have taken up to 5 years). This forced the Chinese to

use any available ships, including river boats, in order to achieve

readiness. Most importantly, the Chinese, then under Kublai's control,

were forced to build many ships quickly in order to contribute to the

fleet in both of the invasions. Hayashida theorizes that, had Kublai

used standard, well constructed ocean going ships, which have a curved keel to prevent capsizing, his navy might have survived the journey to and from Japan and might have conquered it as intended. David Nicolle writes in The Mongol Warlords that

"Huge losses had also been suffered in terms of casualties and sheer

expense, while the myth of Mongol invincibility had been shattered

throughout eastern Asia." He also wrote that Kublai Khan was determined

to mount a third invasion, despite the horrendous cost to the economy

and to his and Mongol prestige of the first two defeats, and only his

death and the unanimous agreement of his advisers not to invade

prevented such a third attempt. After his first invasion of Japan, in response, the Japanese pirates, known as Wokou,

raided Korea. But the Mongol - Korean forces pushed them back, and the

Wokou pirates experienced a low point of their activity due to the

higher degree of military preparedness in the Goryeo and the Kamakura.

In 1293, the Yuan navy captured 100 Japanese from Okinawa. Kublai Khan also twice invaded Đại Việt. When Kublai became the Great Khan in 1260, the Trần Dynasty sent tribute every 3 years and received a darugachi. But

their king soon declined to attend the court in person. The first

incursion (the second Mongol invasion of Đại Việt) began in December

1284 when Mongols under the command of Toghan, the prince of Kublai Khan, crossed the border and quickly occupied Thăng Long (now Hanoi) in January 1285 after the victorious battle of Omar in Vạn Kiếp (north east of Hanoi). At the same time Sogetu from Champa moved

northward and rapidly marched to Nghe An (in the north central region

of Vietnam now) where the army of the Tran under general Tran Kien

surrendered to him. However, the Trần kings and

the commander-in-chief Trần Hưng Đạo changed tactics from defence to

attack and struck against the Mongols. In April, General Trần Quang Khải defeated Sogetu in Chuong Duong (now part of Hanoi) and then the Trần kings won a big battle in Tây Kết where Sogetu died. Soon after, general Trần Nhật Duật also won a battle in Hàm Tử (now part of Hưng Yên) while Toghan was defeated by General Trần Hưng Đạo and Kublai Khan failed in his first attempt to invade Đại Việt. Toghan had

to hide himself inside a bronze pipe to avoid being killed by the Đại

Việt archers; this shameful act became a disastrous humiliation for the

Mongol Empire and for Toghan himself. After

his first failure, Kublai wanted to install Nhan Tong's brother Tran

Ich Tac, who had defected to the Mongols, as king of Annam, but

hardship in the Yuan's supply base in Hunan, and Kaidu's invasion aborted his planned invasion. In 1285 the Brigung sect rebelled, attacking monasteries of Paghspa's sect in Tibet. The Chagatayid Khan, Duwa, came in to aid the rebels, and laid siege to Kara-Kocho while defeating Kublai's garrisons in the Tarim basin. Kaidu destroyed an army at Beshbalik and occupied the city the next year. Many Uyghurs abandoned Kashgar for

safer bases back east in the Yuan. Only after Kublai's grandson

Buqa-Temur crushed the resistance of the Brigung sect, killing 10,000

Tibetans in 1291, Tibet was fully pacified. The

second invasion of Đại Việt by Kublai Khan began in 1287 and was better

organized than the previous effort, utilizing a large fleet and

plentiful stocks of food. The Mongols, under the command of Toghan, moved to Vạn Kiếp (from the north west) and met the infantry and cavalry of Omar (coming

by another way along the Red River) and there they quickly won the

battle. The naval fleet rapidly attained victory in Vân Đồn (near Ha Long Bay) but they left the heavy cargo ships stocked with food behind which General Trần Khánh Dư quickly captured. As foreseen, the Mongolians in Thăng Long (now Hanoi)

suffered an acute shortage of sustenance. Without any news about the

supply fleet Toghan found himself in a tight corner and had to order

his army to retreat to Vạn Kiếp. This was when Đại Việt's Army began

the general offensive by recapturing a number of locations occupied by

the Mongol invaders. Groups of infantry were given orders to attack the

Mongols in Vạn Kiếp. Toghan had to split his army into two and retreat. In early April the naval fleet led by Kublai's Kipchak commander Omar and escorted by infantry fled home along the Bạch Đằng river. As bridges and roads were destroyed and attacks were launched by Đại

Việt's troops, the Mongols reached Bạch Đằng without an infantry

escort. Đại Việt's small flotilla engaged in battle and pretended to

retreat. The Mongols eagerly pursued Đại Việt troops and fell into

their prearranged battlefield. "Thousands" of Đại Việt's small boats

from both banks quickly appeared, fiercely launched the attack and

broke the combat formation of the enemy. Meeting a sudden and strong

attack, the Mongols tried to withdraw to the sea in panic. Hitting the

stakes, their boats were halted, many of which were broken and sank. At

that time, a number of fire rafts quickly rushed toward them.

Frightened, the Mongolian troops jumped down to get to the banks where

they were dealt a heavy blow by an army led by the Trần king and Trần Hưng Đạo.

The Mongolian naval fleet was totally destroyed and Omar was captured.

At the same time, Đại Việt's Army made continuous attacks and smashed

to pieces Toghan's army on its route of withdrawal through Lạng Sơn. Toghan risked his life making a shortcut through thick forest to flee home. Nevertheless, the Đại Việt and the Kingdom of Champa had recognized Kublai's supremacy in order to avoid more conflicts. Three expeditions against Burma (1277, 1283, 1287) brought the Mongol forces to the Irrawaddy delta, and the Mongols captured Bagan, the capital of Pagan Kingdom in Burma, and established their puppet government. Kublai had to be content with the acknowledgment of a formal suzerainty again but the Burmese finally became tributary state and sent tributes until the expulsion of the Mongols from China. The Khmer kingdom of Cambodia and small states in Malay and South India submitted to Kublai's rule between 1278 - 1294. Mongol interests in these parts had always been purely commercial and tributary relationship. During the last years of his reign Kublai launched a naval punitive expedition of 20-30,000 men against the Javanese kingdom of Singhasari (1293), but the Mongol forces were compelled to withdraw, by the Majapahit Dynasty, after considerable losses of more than 3,000 troops. In 1294, two Thai kingdoms of Sukhotai and Chiangmai became vassal states of Kublai's empire.

The Mongol forces made several attacks on Sakhalin, beginning in 1264 and continuing until 1308. Economically, the conquest of new peoples provided further wealth for the tribute-based Mongol Dynasty. The Nivkhs and the Orokhs were subjugated by the Mongols. However, the Ainu people raided Mongol posts and fought with the indigenous people of Sakhalin, who submitted to the Great Khan. Finally, the Ainu tribes accepted Mongol supremacy in 1308. Under

Kublai, the opening of direct contact between East Asia and the West,

made possible by the Mongol control of the central Asian trade routes

and facilitated by the presence of efficient postal services, was

another spectacular phenomenon in the Mongol Empire. In the beginning

of the 13th century, large numbers of Europeans and Central Asians -

merchants, travelers, and missionaries of different orders - made their

way to China. The presence of the Mongol power also enabled throngs of

Chinese, bent on warfare or trade, to make their appearance everywhere

in the Mongol Empire, all the way to Russia, Persia, and Mesopotamia. There were several direct exchanges of missions between the Pope and the Great Khan, though each with a different motive. In 1266 Kublai entrusted the Venetian merchants,

the Polo brothers, to carry a request to the Pope for a hundred

Christian scholars and engineers. The Polos arrived in Rome in 1269,

receiving an audience from the future Pope Gregory X, and they set out with his blessing but no scholars. Marco Polo,

Niccolo's son, who accompanied his father on this trip, was probably

the best-known foreign visitor ever to set foot in China and Mongolia.

It is said that he spent the next 17 years (1275 – 1292) under Kublai

Khan, including official service in the salt administration and trips

through the provinces of Yunnan and Fukien.

Although the flaws in his description of China have tempted modern

historians to dispute his sojourn in the Middle Kingdom, the popularity

of his journal, Description of the World, was such that it subsequently generated unprecedented enthusiasm in Europe for going east. Marco Polo had his East Asian counterpart in Rabban Sauma, a Nestorian monk born around Khanbalik/Dadu (modern Beijing). He crossed central Asia to the Il-Khan's court in Iran in

1278 and was one of those whom the Mongols sent to Europe to seek

Christian help against Islam. There must have been countless numbers of

unknown others who crossed the Continent, spreading information about

their land and bringing with them artifacts of their culture. Under

Kublai, the first direct contact and cultural interchange between China

and the West, however limited in scope, had become a reality never

before achieved. Kublai

used traditional decimal organization of the Mongol Empire and set up

special gerfalcon posts exclusively for the highest officials in 1261.

He adopted Chinese political and cultural models, and also worked to

minimize the influences of regional lords who had held immense power

before and during the Song Dynasty. Kublai heavily relied on his

Chinese advisers until 1276. Nevertheless, his mistrust of ethnic Han Chinese caused him to appoint Mongols,

Central Asians, Muslims and few Europeans to high positions more often

than Han Chinese. Kublai began to suspect Han Chinese when his Chinese

minister's son-in-law revolted against him while he was fighting

against Ariq Böke in Mongolia, though he continued to invite and use many Han Chinese advisers such as Liu Bingzhong and Xu Heng. He employed 66 Uyghur Turks, 21 of whom were resident commissioner running Chinese districts. In 1262 he appointed his wife's Muslim provisioner, Ahmad Fanakati, fiscal commissioner in chief and prefect of his Inner Mongolian capital, Xanadu (Shangdu). Kublai

also appointed Phagspa Lama his state preceptor, giving him power over

all the empire's Buddhist monks. In 1270, after Phagspa created the Square script,

he was promoted to imperial preceptor. Kublai established the Supreme

Control Commission under Phagspa to administer affairs of both Tibetan

and Chinese monks. During Phagspa's absence in Tibet, the Tibetan monk

Sangha rose to high office and had the office renamed the Commission

for Buddhist and Tibetan Affairs. Assyrian Christians served Kublai and the Yuan court created Commission for the Promotion of Religion under the Assyrian physician, Isa, to supervise Christian churches and other religious affairs. The Khagan set up a Muslim medical office for the court in 1270, a Directorate of Islamic astronomy in

1271, and a Muslim school for the sons of the dynasty in 1289. With

deaths of his entrusted Chinese officials such as Liu Bingzhong (1274),

Shi Tiaze (1275), Zhao Bi (1276) and Don Weibing (1278), Kublai turned

to non-Chinese officials. Kublai appointed Ahmad Fanakati head of a

department of state affairs. In 1286, Tibetan Sangha became the dynasty's chief fiscal officer. However, their corruption later embittered Kublai. Thenceforwards, Kublai came to rely wholly on younger Mongol aristocrats. While Antong of the Jalayir, and Bayan of the Baarin served as grand councillors from 1265, Oz-temur of the Arulad headed the censorate. Borokhula's descendant, Ochicher, headed a kheshig and the palace provision commission. In

the 8th Year of Zhiyuan (1271), Kublai Khan officially declared the

creation of the Yuan Dynasty, and proclaimed the capital to be at Dadu (Chinese: 大都; Wade–Giles: Ta-tu, lit. "Great Capital", known as Daidu to the Mongols, at today's Beijing) in the following year. His summer capital was in Shangdu (Chinese: 上都, "Upper Capital", a.k.a. Xanadu, near what today is Dolonnur). To unify China,

Kublai Khan began a massive offensive against the remnants of the

Southern Song Dynasty in the 11th year of Zhiyuan (1274), and finally

destroyed the Song Dynasty in the 16th year of Zhiyuan (1279), unifying

the country at last. China proper, Korea and Mongolia itself were administered in 11 provinces during his reign with a governor and vice-governor each. Aside from the 11 provinces was the Central Region (Chinese: 腹裏),

consisting of much of present-day North China, was considered the most

important region of the dynasty and directly governed by the

Zhongshusheng (Chinese: 中書省, "Department of Central Governing") at Dadu. In addition, Tibet was governed by another top-level administrative department called the Xuanzheng Institute (Chinese: 宣政院). He ruled well, promoting economic growth with the rebuilding of the Grand Canal,

repairing public buildings, and extending highways. However, Kublai

Khan's domestic policy also included some aspects of the old Mongol

living traditions, and as Kublai Khan continued his reign, these

traditions would clash more and more frequently with traditional

Chinese economic and social culture. Kublai decreed that partner

merchants of the Mongols should be subject to taxes in 1263 and set up

the Office of Market Taxes to supervise them in 1268. With the Mongol

conquest of the Song, the merchants expanded their sphere of operations

to the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean. In 1286 maritime trade was put under the Office of Market Taxes. The main source of revenue of the government was the salt monopoly. The Mongol administration issued paper currencies from 1227 on. In

August 1260, Kublai created the first unified paper currency with bills

that circulated throughout the Yuan with no expiration date. To guard

against devaluation, the currency was convertible with silver and gold,

and the government accepted tax payments in paper currency. In 1273, he

issued a new series of state sponsored bills to finance his conquest of

the Song, although eventually a lack of fiscal discipline and inflation

turned this move into an economic disaster in the later course of the

dynasty. It was required to pay only in the form of paper money called Chao.

To ensure its use in circles, Kublai's government confiscated gold and

silver from private citizens as well as foreign merchants. But traders

received government issued notes in exchange. That is why Kublai Khan

is considered to be the first of fiat money makers.

The paper bills made collecting taxes and administering the huge empire

much easier while reducing the cost of transporting coins. In 1287 Kublai's minister Sangha created a new currency, Zhiyuan, to deal with the budget shortfall. It was non-convertible and denominated in copper cash. Later Gaykhatu of the Ilkhanate attempted to adopt the system in Persia and Middle east, which was however a complete failure, and he was assassinated shortly after that. He encouraged Asian arts and demonstrated religious tolerance. Despite his anti-Taoist edicts, Kublai respected the Taoist master and appointed Zhang Liushan the patriarch of Taoist Xuanjiao order. Under

Zhang's advice, Taoist temples were put under the Academy of Scholarly

Worthies. The empire was visited by several Europeans, notably Marco Polo in the 1270s who may have seen the summer capital Shangdu. After Kublai was proclaimed Khagan at his residence in Shangdu on

5 May 1260, he began to organize the country. Zhang Wenqian, who was a

friend of Guo and like him was a central government official, was sent

by Kublai Khan in 1260 to Daming where unrest had been reported in the

local population. Guo accompanied Zhang on his mission. Guo was not

only interested in engineering, but he was also an expert astronomer.

In particular he was a skilled instrument maker and understood that

good astronomical observations depended on expertly made instruments.

He now began to construct astronomical instruments, including water clocks for accurate timing and armillary spheres which represent the celestial globe. Turkestani architect Ikhtiyar al-Din (also known as Igder) designed the buildings of the city of Khagan or Khanbalic. The Great Khan also employed many foreign artists to build his new capital. One of them named Arniko from Nepal built the White Stupa which was the largest structure in Khanbalic/Dadu. Zhang

advised Kublai Khan that his friend Guo was a leading expert in

hydraulic engineering. Kublai knew the importance of water management,

for irrigation, transport of grain, and flood control, and he asked Guo

to look at these aspects in the area between Dadu (now Beijing or

Peking) and the Yellow River. To provide Dadu with a new supply of

water, Guo found the Baifu spring in the Shenshan Mountain and had a

30 km channel built to bring the water to Dadu. He proposed

connecting the water supply across different river basins, built new

canals with many sluices to control the water level, and achieved great

success with the improvements which he was able to make. This pleased

Kublai Khan and led to Guo being asked to undertake similar projects in

other parts of the country. In 1264 he was asked to go to Gansu

province to repair the damage that had been caused to the irrigation

systems by the years of war during the Mongol advance through the

region. Guo travelled extensively along with his friend Zhang taking

notes of the work which needed to be done to unblock damaged parts of

the system and to make improvements to its efficiency. He sent his

report directly to Kublai Khan.

During the conquest of the Jin, Genghis Khan's younger brothers received large appanages in Manchuria. Descendants

of them strongly supported Kublai's coronation in 1260, but the younger

generation desired more independence. Kublai enforced Ogedei Khan's

regulations that the Mongol noblemen could appoint overseers, along

with the Great Khan's special officials, in their appanages, but

otherwise respected appanage rights. His son Manggala established

direct control over Singan and Shansi in 1272. In 1274 Kublai Khan appointed Lian Xixian to investigate abuses of power by Mongol appanage holders in Manchuria. Lia-tung region was brought immediately under the Khagan's control, in 1284, eliminating autonomy of the Mongol nobles there. Threatened by the advance of the Great Khan's bureaucratization, Belgutei's fourth generation descendant, Nayan (not to be confused with Temuge's descendant Nayan), instigated revolt in 1287. Nayan attempted to link up with Kublai's competitor Kaidu in Central Asia. Manchuria's native Jurchens and Water Tatars, who had suffered famine, supported Nayan. Virtually all the fraternal lines under Qadaan, a descendant of Khachiun, and Shikqtur, a grandson of Qasar, joined his rebellion. Because

Nayan was a popular prince, Ebugen, a grandson of Genghis Khan's son

Khulgen, and the family of Khuden, a younger brother of Guyuk Khan, contributed troops for his rebellion. The

rebellion was crippled by early detection and timid leadership. Kublai

sent Bayan to keep Nayan and Kaidu apart by occupying Karakorum, while

he himself led another army against the rebels in

Manchuria. Kublai's commander Oz Temur's Mongol force attacked Nayan's

60,000 green soldiers on June 14, while Chinese and Alan guards under

Li Ting protected Kublai. The army of Chungnyeol of Goryeo assisted Kublai in battle. After the hard fight, Nayan's troops withdrew behind their carts, and Li Ting began bombardment and

attacked Nayan's camp that night. Kublai's force pursued Nayan, who was

eventually captured and executed in the traditional way for princes,

without shedding of blood. Meanwhile, the rebel prince Shikqtur invaded the Chinese districts in Liaoning but was defeated within a month. Kaidu pulled back westward to avoid a battle. However, Kaidu defeated a major Yuan army in Khangai and briefly occupied Karakorum in 1289. Kaidu had ridden away before Kublai himself mobilized a larger army. Widespread

but uncoordinated risings of Nayan's supporters continued until 1289

but were ruthlessly repressed. The rebel princes' troops were taken

from them and redistributed among the imperial family. Kublai harshly punished the darugachis appointed by the rebels in Mongolia and Manchuria. This

rebellion forced Kublai to approve the creation of the Liaoyang Branch

Secretariat on December 4, 1287, while rewarding loyal fraternal

princes. Kublai dispatched his grandson Gammala to Burkhan Khaldun in 1291. Because Kublai wanted to make sure that he laid claims to the sacred place (Ikh Khorig),

Burkhan Khaldun, where Genghis was buried, Mongolia was strongly

protected by the Kublaids. With Bayan in control of Karakorum and

reestablishing control over surrounding areas in 1293, Kublai's rival relative Kaidu did not attempt anything large-scale for the next three years. From 1293 on Kublai's army cleared Kaidu's forces out of Central Siberian Plateau. Kublai Khan originally designated his son Chingen-Temur (Zhenjin)

as his successor. Chingen-Temur became the head of Zhongshusheng

("Department of Central Governing"), and actively administrated the

dynasty in the Confucian fashion.

After Nomukhan returned from the captivity in the Golden Horde, he

expressed his resentment that Chingen-Temur had been made heir

apparent. However, he was banished north. An official proposed that

Kublai's abdicate in favor Chingen Temur in 1285. This action angered

the Khagan, and Kublai refused to see his son. Unfortunately,

Chingen-Temur died in 1285, 9 years before his father. Kublai mourned

and remained very close to his wife, Bairam (also known as Kokejin).

With the death of Chabi, he began to withdraw from direct contact with

his advisers, issuing instructions through one of his other queens

Nambui. Kublai Khan, on the other hand, developed severe gout in

the later part of his life. He also gained weight due to a fondness for

eating animal organs and other delicacies. This also more than likely

increased the amount of purines in his blood, leading to his problems with gout. His

illness may have been related to the deaths of not only his favorite

wife, but also his chosen heir Zhenjin. Before his death, Kublai made Chingen-Temur's son Temür the

new Crown Prince, who in turn became the sixth Khagan of the Mongol

Empire and the second ruler of the Yuan Dynasty after the death of

Kublai Khan. Seeking an old companion to comfort him in his final

illness, the palace staff could choose only Bayan, more than 30 years

his junior. Kublai weakened steadily, and on 18 February 1294 he died.

Two days later, the funeral cortege was ready and set out for the burial place of the khans in Mongolia. Kublai married Tegulen at first but she died very early. Then he married Chabi Khatun of the Khunggirat.

Chabi was his most beloved empress. After her death in 1286, Kublai

married her young cousin, Nambui, in accordance with Chabi's wish. Kublai's

seizure of power in 1260 pushed the Mongolian Empire into a new

direction. Despite his controversial election, which accelerated the

disunity of the Mongols, his willingness to formalize the Mongol

realm's symbiotic relation with China gave the Mongolian Empire a

cultural and administrative brilliance that impressed the world. Kublai

and his predecessors' conquests were largely responsible for

re-creating a unified, militarily powerful China. The Mongol rule of Tibet, Xinjiang, and Mongolia proper from a capital at modern Beijing also supplied the precedent for the Qing Dynasty's Inner Asian Empire.

Kublai

Khan twice attempted to invade Japan; however, both times, it is

believed that bad weather, or a flaw in the design of ships that were

based on river boats without keels nevertheless destroyed his fleets.

The first attempt took place in 1274, with a fleet of 900 ships. The

second invasion occurred in 1281.The Mongols sent two separate forces

this time; an impressive force of 900 ships containing 40,000 Korean,

Chinese, and Mongol troops set out from Masan, while an even larger

force of 100,000 sailed from southern China in 3,500 ships, each close

to 240 feet (73 m) long. The fleet was hastily assembled and

ill-equipped to handle the sea. In

November, they sailed out into the treacherous waters that separated

Korea and Japan by 110 miles. The Mongols easily took over Tsushima

Island about halfway across the strait and then Ika Island closer to

Kyushu. The Korean fleet reached Hakata Bay on June 23, 1281 landing

its forces and animals, but the ships from China were nowhere to be

seen. The samurai warriors rode out against the Mongol forces

for individual combat, but the Mongols held their formation. As usual,

the Mongols fought as a united force, not as individuals. Instead of

coming out for duels, the Mongols bombarded the samurai with exploding

missiles and showered them in arrows. Eventually, the remaining

Japanese withdrew from the coastal zone inland to a fortress. The

Mongol forces did not chase the fleeting Japanese into an area about

which they lacked reliable intelligence at that time.