<Back to Index>

- Geneticist Thomas Hunt Morgan, 1866

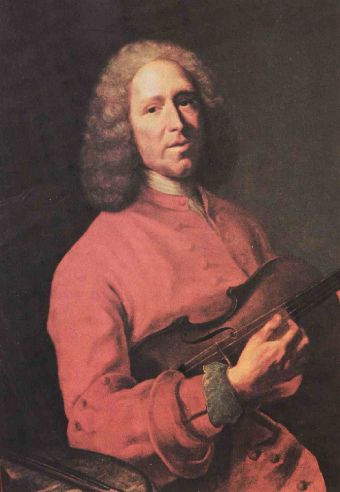

- Composer Jean Philippe Rameau, 1683

- 7th Prime Minister of Australia William Morris "Billy" Hughes, 1862

PAGE SPONSOR

Jean-Philippe Rameau (September 25, 1683, Dijon – September 12, 1764) was one of the most important French composers and music theorists of the Baroque era. He replaced Jean-Baptiste Lully as the dominant composer of French opera and is also considered the leading French composer for the harpsichord of his time, alongside François Couperin.

Little is known about Rameau's early years, and it was not until the 1720s that he won fame as a major theorist of music with his Treatise on Harmony (1722). He was almost 50 before he embarked on the operatic career on which his reputation chiefly rests. His debut, Hippolyte et Aricie (1733), caused a great stir and was fiercely attacked for its revolutionary use of harmony by the supporters of Lully's style of music. Nevertheless, Rameau's pre-eminence in the field of French opera was soon acknowledged, and he was later attacked as an "establishment" composer by those who favoured Italian opera during the controversy known as the Querelle des Bouffons in the 1750s. Rameau's music had gone out of fashion by the end of the 18th century, and it was not until the 20th that serious efforts were made to revive it. Today, he enjoys renewed appreciation with performances and recordings of his music ever more frequent.

The

details of Rameau's life are generally obscure, especially concerning

his first forty years, before he moved to Paris for good. He was a

secretive man, and even his wife knew nothing of his early life, which explains the scarcity of

biographical information available.

He was born on September 25, 1683 and baptised the same day. His father, Jean, worked as an

organist in several churches around Dijon,

and his mother, Claudine Demartinécourt, was the daughter of a

notary. The couple had eleven children (five girls and six boys), of

which Jean-Philippe was the seventh. Rameau was taught music before he

could read or write. He was educated at the Jesuit college

at Godrans, but he was not a good pupil and disrupted classes with his

singing, later claiming that his passion for opera had begun at the age

of twelve. Initially

intended for the law, Rameau decided he wanted to be a musician, and

his father sent him to Italy, where he stayed for a short while in Milan.

On his return, he worked as a violinist in travelling companies and

then as an organist in provincial cathedrals before moving to Paris for the first time. Here, in 1706, he published his

earliest known compositions: the harpsichord works that make up his

first book of Pièces

de clavecin, which show the influence of his friend Louis Marchand. In

1709, he moved back to Dijon to take over his father's job as organist

in the main church. The contract was for six years, but Rameau left

before then and took up similar posts in Lyon and Clermont. During this

period, he composed motets for church performance as

well as secular cantatas.

In 1722, he returned to Paris for good, and here he published his most

important work of music theory, Traité

de l'harmonie (Treatise

on Harmony). This soon won him a great reputation, and it was

followed in 1726 by his Nouveau

système de musique théorique. In 1724 and 1729 (or 1730), he

also published two more collections of harpsichord pieces. Rameau took his first tentative

steps into composing stage music when the writer Alexis Piron asked him to provide songs

for his popular comic plays written for the Paris Fairs. Four

collaborations followed, beginning with L'endriague in 1723; none of the music

has survived. On

February 25, 1726, Rameau married the 19 year old Marie-Louise Mangot,

who came from a musical family from Lyon and was a good singer and

instrumentalist. The couple would have four children, two boys and two

girls, and the marriage is said to have been a happy one. In

spite of his fame as a music theorist, Rameau had trouble finding a

post as an organist in Paris. It

was not until he was approaching 50 that Rameau decided to embark on

the operatic career on which his fame as a composer mainly rests. He

had already approached writer Houdar de la Motte for a libretto in

1727, but nothing came of it; he was finally inspired to try his hand

at the prestigious genre of tragédie

en musique after

seeing

Montéclair's Jephté in 1732. Rameau's Hippolyte et

Aricie premiered

at the Académie Royale de Musique on October 1, 1733. It was

immediately recognised as the most significant opera to appear in

France since the death of Lully,

but audiences were split over whether this was a good thing or a bad

thing. Some, such as the composer André

Campra,

were stunned by its originality and wealth of invention; others found

its harmonic innovations discordant and saw the work as an attack on

the French musical tradition. The two camps, the so-called Lullyistes

and the Rameauneurs, fought a pamphlet war over the issue for the rest

of the decade. Just

before this time, Rameau had made the acquaintance of powerful financier Alexandre Le

Riche de La Poupelinière,

who became his patron until 1753. La Pouplinière's mistress (and

later, wife), Thérèse des Hayes, was Rameau's pupil and a

great admirer of his music. In 1731, Rameau became the conductor of La

Pouplinière's private orchestra, which was of an extremely high

quality. He held the post for 22 years; he was succeeded by Johann Stamitz and then Gossec. La Pouplinière's salon

enabled Rameau to meet some of the leading cultural figures of the day,

including Voltaire,

who soon began collaborating with the composer. Their first project, the

tragédie en musique Samson,

was abandoned because an opera on a religious theme by Voltaire — a

notorious critic of the Church — was likely to be banned by the

authorities. Meanwhile, Rameau had

introduced his new musical style into the lighter genre of the opéra-ballet with the highly successful Les Indes

galantes. It was followed by two tragédies en

musique, Castor et

Pollux (1737) and Dardanus (1739), and another opéra-ballet, Les fêtes

d'Hébé (also

1739). All these operas of the 1730s are among Rameau's most highly

regarded works. However, the composer followed

them with six years of silence, in which the only work he produced was

a new version of Dardanus (1744).

The reason for this interval in the composer's creative life is

unknown, although it is possible he had a falling-out with the

authorities at the Académie royale de la musique. The

year 1745 was a watershed in Rameau's career. He received several

commissions from the court for works to celebrate the French victory at

the Battle of

Fontenoy and the

marriage of the Dauphin to a Spanish princess.

Rameau produced his most important comic opera, Platée,

as well as two collaborations with Voltaire: the opéra-ballet Le temple de la

gloire and

the comédie-ballet La princesse de

Navarre. They

gained Rameau official recognition; he was granted the title

"Compositeur du Cabinet du Roi" and given a substantial pension. 1745 also saw the beginning of

the bitter enmity between Rameau and

Jean-Jacques

Rousseau. Though best known today as a thinker, Rousseau had

ambitions to be a composer. He had written an opera, Les muses galantes (inspired by Rameau's Indes galantes),

but Rameau was unimpressed by this musical tribute. At the end of 1745,

Voltaire and Rameau, who were busy on other works, commissioned

Rousseau to turn La

Princesse de Navarre into

a new opera, with linking recitative called Les fêtes

de Ramire.

Rousseau then claimed the two had stolen the credit for the words and

music he had contributed, though musicologists have been able to

identify almost nothing of the piece as Rousseau's work. Nevertheless,

the embittered Rousseau nursed a grudge against Rameau for the rest of

his life. Rousseau

was a major participant in the second great quarrel that erupted over

Rameau's work, the so-called Querelle des

Bouffons of

1752–54, which pitted French tragédie

en musique against

Italian opera buffa.

This time, Rameau was accused of being out of date and his music too

complicated in comparison with the simplicity and "naturalness" of a

work like Pergolesi's La serva padrona. In the mid 1750s, Rameau

criticised Rousseau's contributions to the musical articles in the Encyclopédie,

which led to a quarrel with the leading philosophes d'Alembert and Diderot. As a result, Rameau became a

character in Diderot's then unpublished dialogue, Le neveu de Rameau (Rameau's Nephew). In

1753, La Pouplinière took a scheming musician,

Jeanne-Thérèse Goermans, as his mistress. The daughter of

harpsichord maker Jacques

Goermans,

she went by the name of Madame de Saint-Aubin, and her opportunistic

husband pushed her into the arms of the rich financier. She had La

Pouplinière engage the services of the Bohemian composer Johann Stamitz,

who succeeded Rameau after a breach developed between Rameau and his

patron; however, by then, Rameau no longer needed La

Pouplinière's financial support and protection. Rameau

pursued his activities as a theorist and composer until his death. He

lived with his wife and two of his children in his large suite of rooms

in Rue des Bons-Enfants, which he would leave every day, lost in

thought, to take a solitary walk in the nearby gardens of the

Palais-Royal or the Tuileries. Sometimes he would meet the young writer

Chabanon, who noted some of Rameau's disillusioned confidential remarks: "Day by day, I'm

acquiring more good taste, but I no longer have any genius" and "The

imagination is worn out in my old head; it's not wise at this age

wanting to practise arts that are nothing but imagination." Rameau

composed prolifically in the late 1740s and early 1750s. After that,

his rate of productivity dropped off, probably due to old age and ill

health, although he was still able to write another comic opera, Les Paladins,

in 1760. This was due to be followed by a final tragédie en

musique, Les

Boréades; but for unknown reasons, the opera was

never produced and had to wait until the late 20th century for a proper

staging. Rameau died on September 12,

1764 after suffering from a fever. He was buried in the church of St. Eustache,

Paris the following day. While

the details of his biography are vague and fragmentary, the details of

Rameau's personal and family life are almost completely obscure.

Rameau's music, so graceful and attractive, completely contradicts the

man's public image and what we know of his character as described (or

perhaps unfairly caricatured) by Diderot in his satirical novel Le Neveu de

Rameau.

Throughout his life, music was his consuming passion. It occupied his

entire thinking; Philippe Beaussant calls him a monomaniac. Piron

explained that "His heart and soul were in his harpsichord; once he had

shut its lid, there was no one home." Physically, Rameau was tall and

exceptionally thin, as

can be seen by the sketches we have of him, including a famous portrait

by Carmontelle. He had a "loud voice." His speech was difficult to

understand, just like his handwriting, which was never fluent. As a

man, he was secretive, solitary, irritable, proud of his own

achievements (more as a theorist than as a composer), brusque with

those who contradicted him, and quick to anger. It is difficult to

imagine him among the leading wits, including Voltaire (to whom he

bears more than a passing physical resemblance), who frequented La

Pouplinière's salon; his music was his passport, and it made up

for his lack of social graces. His

enemies exaggerated his faults; e.g. his supposed miserliness. In fact,

it seems that his thriftiness was the result of long years spent in

obscurity (when his income was uncertain and scanty) rather than part

of his character, because he could also be generous. We know that he

helped his nephew Jean-François when he came to Paris and also

helped establish the career of Claude-Bénigne

Balbastre in

the capital. Furthermore, he gave his daughter Marie-Louise a

considerable dowry when she became a Visitandine nun in 1750, and he

paid a pension to one of his sisters when she became ill. Financial

security came late to him, following the success of his stage works and

the grant of a royal pension (a few months before his death, he was

also ennobled and made a knight of the Ordre de Saint-Michel). But he

did not change his way of life, keeping his worn-out clothes, his

single pair of shoes, and his old furniture. After his death, it was

discovered that he only possessed one dilapidated single-keyboard

harpsichord in his rooms in Rue des

Bons-Enfants, yet he also had a bag containing 1691 gold louis.