<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Jacques Charles François Sturm, 1803

- Novelist Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, 1547

- Vice Admiral of the White Horatio Nelson, 1758

PAGE SPONSOR

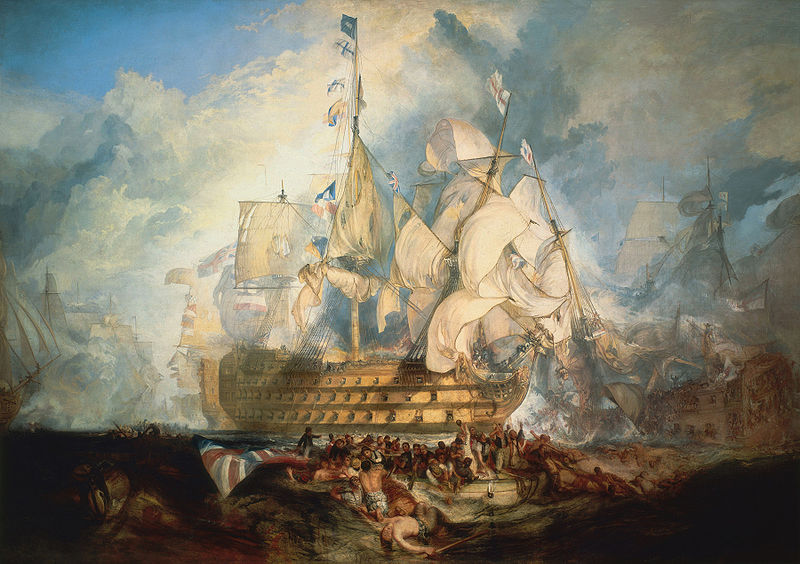

Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronté, KB (29 September 1758 – 21 October 1805) was an English flag officer famous for his service in the Royal Navy, particularly during the Napoleonic Wars. Of his several victories, the most well known and notable was The Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, during which he was shot and expired towards the battle's end.

Nelson was born into a moderately prosperous Norfolk family and joined the navy through the influence of his uncle, Maurice Suckling. He rose rapidly through the ranks and served with leading naval

commanders of the period before obtaining his own command in 1778. He

developed a reputation in the service through his personal valour and

firm grasp of tactics but suffered periods of illness and unemployment

after the end of the American War of Independence. The outbreak of the French Revolutionary Wars allowed Nelson to return to service, where he was particularly active in the Mediterranean. He fought in several minor engagements off Toulon and was important in the capture of Corsica and subsequent diplomatic duties with the Italian states. In 1797, he distinguished himself while in command of HMS Captain at the Battle of Cape St Vincent. Shortly after the battle, Nelson took part in the Battle of Santa Cruz de Tenerife,

where his attack was defeated and he was badly wounded, losing his

right arm, and was forced to return to England to recuperate. The

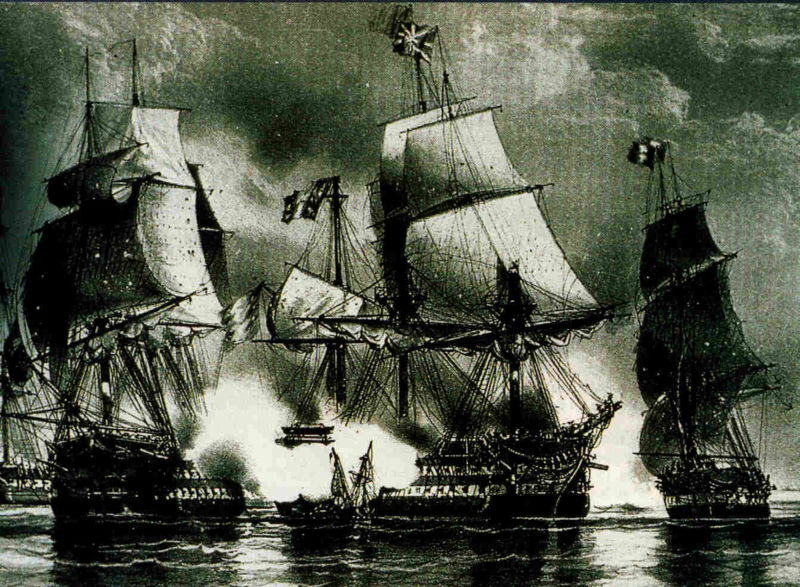

following year, he won a decisive victory over the French at the Battle of the Nile and remained in the Mediterranean to support the Kingdom of Naples against a French invasion. In 1801, he was dispatched to the Baltic and won another victory, this time over the Danes at the Battle of Copenhagen. He subsequently commanded the blockade of the French and Spanish fleets at Toulon and, after their escape, chased them to the West Indies and back but failed to bring them to battle. After a brief return to England, he took over the Cádiz blockade in 1805. On 21 October 1805, the Franco-Spanish fleet came out of port, and Nelson's fleet engaged them at the Battle of Trafalgar.

The battle was Britain's greatest naval victory, but Nelson was hit by

a French sharpshooter and mortally wounded. His body was brought back

to England where he was accorded a state funeral. Nelson was noted for his ability to inspire and bring out the best in his men: the 'Nelson touch'.

His grasp of strategy and unconventional tactics produced a number of

decisive victories. Some aspects of his behaviour were controversial

during his lifetime and after: he began a notorious affair with Emma, Lady Hamilton while

both were married, which lasted until his death. Also, his actions

during the Neapolitan campaign resulted in allegations of excessive

brutality. Nelson could at times be vain, insecure and overly anxious

for recognition, but he was also zealous, patriotic and dutiful, as

well as courageous. He was wounded several times in combat, losing one

arm and the sight in one eye. His death at Trafalgar secured his

position as one of England's most heroic figures. Numerous monuments,

including Nelson's Column in Trafalgar Square, London, have been created in his memory and his legacy remains highly influential. Horatio Nelson was born on 29 September 1758 in a rectory in Burnham Thorpe, Norfolk, England, the sixth of eleven children of the Reverend Edmund Nelson and his wife Catherine. His mother, who died when he was nine, was a grandniece of Sir Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford, the de facto first Prime Minister of Great Britain. She lived in the village of Barsham, Suffolk, and married the Reverend Edmund Nelson at Beccles church, Suffolk, in 1749. Nelson attended Paston Grammar School, North Walsham, until he was 12 years old, and also attended King Edward VI’s Grammar School in Norwich. His naval career began on 1 January 1771, when he reported to the third-rate HMS Raisonnable as an Ordinary Seaman and coxswain under his maternal uncle, Captain Maurice Suckling, who commanded the vessel. Shortly after reporting aboard, Nelson was appointed a midshipman and began officer training. Early in his service, Nelson discovered that he suffered from seasickness, a chronic complaint that dogged him for the rest of his life.

HMS Raisonnable had been commissioned during a period of tension with Spain, but when this passed Suckling was transferred to the Nore guardship HMS Triumph and

Nelson was despatched to serve aboard the West Indiamen of the merchant

shipping firm of Hibbert, Purrier and Horton, in order to gain

experience at sea. In

this capacity he twice crossed the Atlantic, before returning to serve

under his uncle as the commander of Suckling's longboat, which carried

men and despatches to and from the shore. Nelson then learned of a

planned expedition under the command of Constantine Phipps, intended to survey a passage in the Arctic by which it was hoped that India could be reached: the fabled Northwest Passage. At his nephew's request, Suckling arranged for Nelson to join the expedition and serve as a midshipman aboard the converted bomb vessel HMS Carcass. The expedition reached within ten degrees of the North Pole, but, unable to find a way through the dense ice floes, was forced to turn back. Nelson briefly returned to the Triumph after the expedition's return to Britain in September 1773. Suckling then arranged for his transfer to HMS Seahorse, one of two ships about to sail for the East Indies. Nelson sailed for the East Indies on 19 November 1773 and arrived at the British outpost at Madras on 25 May 1774. Nelson and the Seahorse spent the rest of the year cruising off the coast and escorting merchantmen. With the outbreak of the First Anglo-Maratha War, the British fleet operated in support of the East India Company and in early 1775 the Seahorse was despatched to carry a cargo of the company's money to Bombay. On 19 February two of Hyder Ali's ketches attacked the Seahorse, which drove them off after a brief exchange of fire. This was Nelson's first experience of battle. The

rest of the year he spent escorting convoys, during which he continued

to develop his navigation and ship handling skills. In early 1776

Nelson contracted malaria and became seriously ill. He was discharged from the Seahorse on 14 March and returned to England aboard HMS Dolphin. Nelson

spent the six month voyage recuperating and had almost recovered by the

time he arrived in Britain in September 1776. His patron, Suckling, had

risen to the post of Comptroller of the Navy in 1775, and used his influence to help Nelson gain further promotion. Nelson was appointed acting lieutenant aboard HMS Worcester, which was about to sail to Gibraltar. The Worcester, under the command of Captain Mark Robinson, sailed as a convoy escort on 3 December and returned with another convoy in April 1777. Nelson then travelled to London to take his lieutenant's examination on 9 April; his examining board consisted of Captains John Campbell, Abraham North, and his uncle, Maurice Suckling. Nelson passed, and the next day received his commission and an appointment to HMS Lowestoffe, which was preparing to sail to Jamaica under Captain William Locker. She

sailed on 16 May, arrived on 19 July, and after reprovisioning, carried

out several cruises in Caribbean waters. After the outbreak of the American War of Independence the Worcester took several prizes, one of which was taken into Navy service as the tender Little Lucy. Nelson asked for and was given command of her, and took her on two cruises of his own. As

well as giving him his first taste of command, it gave Nelson the

opportunity to explore his fledgling interest in science. During his

first cruise, Nelson led an expeditionary party to the Caicos Islands, where he made detailed notes of the wildlife and in particular a bird — now believed to be the White-necked Jacobin. Locker, impressed by Nelson's abilities, recommended him to the new commander-in-chief at Jamaica, Sir Peter Parker. Parker duly took Nelson onto his flagship, HMS Bristol. The

entry of the French into the war, in support of the Americans, meant

further targets for Parker's fleet and it took a large number of prizes

towards the end of 1778, which brought Nelson an estimated £400 in prize money. Parker subsequently appointed him as Master and Commander of the brig HMS Badger on 8 December. Nelson and the Badger spent most of 1779 cruising off the Central American coast, ranging as far as the British settlements at British Honduras and Nicaragua, but without much success at interception of enemy prizes. On his return to Port Royal he learned that Parker had promoted him to post-captain on 11 June, and intended to give him another command. Nelson handed over the Badger to Cuthbert Collingwood while he awaited the arrival of his new ship, the 28-gun frigate HMS Hinchinbrook, newly captured from the French. While Nelson waited, news reached Parker that a French fleet under the command of Charles Hector, comte d'Estaing, was approaching Jamaica. Parker hastily organized his defences and

placed Nelson in command of Fort Charles, which covered the approaches

to Kingston. D'Estaing instead headed north, and the anticipated invasion never materialised. Nelson duly took command of the Hinchinbrook on 1 September. The Hinchinbrook sailed

from Port Royal on 5 October 1779 and, in company with other British

ships, proceeded to capture a number of American prizes. On

his return to Jamaica in December, Nelson began to be troubled by a

recurrent attack of malaria, but remained in the West Indies in order

to take part in Major-General John Dalling's attempt to capture the Spanish colonies in Central America, including an assault on the fortress of San Juan in Nicaragua. The Hinchinbrook sailed from Jamaica in February 1780, as an escort for Dalling's invasion force. After sailing up the mouth of the Colorado River, Nelson led a successful assault on a Spanish look-out post. Despite

this quick success, the main force's attack on Fort San Juan was long

and drawn out, though Nelson was praised for his efforts. Parker recalled Nelson and gave him command of the 44-gun frigate HMS Janus. Nelson had however fallen seriously ill in the jungles of Costa Rica, probably from a recurrence of malaria, and was unable to take command. During his time of convalescence he was nursed by a black "doctoress" named Cubah Cornwallis, the mistress of a fellow captain, William Cornwallis. He was discharged in August and returned to Britain aboard HMS Lion, arriving

in late November. Nelson gradually recovered over several months, and

soon began agitating for a command. He was appointed to the frigate HMS Albemarle on 15 August 1781.

Nelson received orders on 23 October to take the newly refitted Albemarle to sea. He was instructed to collect an inbound convoy of the Russia Company at Elsinore, and escort them back to Britain. For this operation, the Admiralty placed the frigates HMS Argo and HMS Enterprize under his command. Nelson

successfully organised the convoy and escorted it into British waters.

He then left the convoy to return to port, but severe storms hampered

him. Gales almost wrecked Albemarle as she was a poorly designed ship and an earlier accident had left her damaged, but Nelson eventually brought her into Portsmouth in February 1782. There the Admiralty ordered him to fit the Albemarle for sea and join the escort for a convoy collecting at Cork to sail for Quebec. Nelson arrived off Newfoundland with the convoy in late May, then detached on a cruise to hunt American privateers.

Nelson was generally unsuccessful; he succeeded only in retaking

several captured British merchant ships and capturing a number of small

fishing boats and assorted craft. In August he had a narrow escape from a far superior French force under Louis-Philippe de Vaudreuil, only evading them after a prolonged chase. Nelson arrived at Quebec on 18 September. He sailed again as part of the escort for a convoy to New York. He arrived in mid-November and reported to Admiral Samuel Hood, commander of the New York station. At Nelson's request, Hood transferred him to his fleet and Albemarle sailed in company with Hood, bound for the West Indies. On their arrival, the British fleet took up position off Jamaica to await the arrival of de Vaudreuil's force. Nelson and the Albemarle were

ordered to scout the numerous passages for signs of the enemy, but it

became clear by early 1783 that the French had eluded Hood. During his scouting operations, Nelson had developed a plan to assault the French garrison of the Turks Islands.

Commanding a small flotilla of frigates and smaller vessels, he landed

a force of 167 seamen and marines early on the morning of 8 March under

a supporting bombardment. The

French were found to be heavily entrenched and after several hours

Nelson called off the assault. Several of the officers involved

criticised Nelson, but Hood does not appear to have reprimanded him. Nelson spent the rest of the war cruising in the West Indies, where he captured a number of French and Spanish prizes. After news of the peace reached Hood, Nelson returned to Britain in late June 1783. Nelson visited France in late 1783, stayed with acquaintances at Saint-Omer,

and briefly attempted to learn French. He returned to England in

January 1784, and attended court as part of Lord Hood's entourage. Influenced by the factional politics of the time, he contemplated standing for Parliament as a supporter of William Pitt, but was unable to find a seat. In 1784 he received command of the frigate HMS Boreas with the assignment to enforce the Navigation Acts in the vicinity of Antigua. The Acts were unpopular with both the Americans and the colonies. Nelson served on the station under Admiral Sir Richard Hughes, and often came into conflict with his superior officer over their differing interpretation of the Acts. The captains of the American vessels Nelson had seized sued him for illegal seizure. As the merchants of Nevis supported the American claim, Nelson was in peril of imprisonment; he remained sequestered on Boreas for eight months until the courts ruled in his favour. In the interim, Nelson met Frances "Fanny" Nisbet, a young widow from a Nevis plantation family. Nelson

and Nisbet were married at Montpelier Estate on the island of Nevis on

11 March 1787, shortly before the end of his tour of duty in the

Caribbean. The

marriage was registered at Fig Tree Church, St. John's Parish, Nevis.

Nelson returned to England in July, with Fanny following later.

Nelson remained with Boreas until she was paid off in November that year. He and Fanny then divided their time between Bath and

London, occasionally visiting Nelson's relations in Norfolk. In 1788,

they settled at Nelson's childhood home at Burnham Thorpe. Now

in reserve on half pay, he attempted to persuade the Admiralty and

other senior figures he was acquainted with, such as Hood, to provide

him with a command. He was unsuccessful as there were too few ships in

the peacetime navy and Hood did not intercede on his behalf. Nelson

spent his time trying to find employment for former crew members,

attending to family affairs, and cajoling contacts in the navy for a

posting. In 1792 the French revolutionary government

annexed the Austrian Netherlands (modern Belgium), which were

traditionally preserved as a buffer state. The Admiralty recalled

Nelson to service and gave him command of the 64-gun HMS Agamemnon in January 1793. On 1 February France declared war.

In May, Nelson sailed as part of a division under the command of Vice-Admiral William Hotham, joined later in the month by the rest of Lord Hood's fleet. The force initially sailed to Gibraltar and, with the intention of establishing naval superiority in the Mediterranean, made their way to Toulon, anchoring off the port in July. Toulon was largely under the control of moderate republicans and royalists, but was threatened by the forces of the National Convention,

which were marching on the city. Short of supplies and doubting their

ability to defend themselves, the city authorities requested that Hood

take the city under his protection. Hood readily acquiesced and sent Nelson to carry despatches to Sardinia and Naples requesting reinforcements. After delivering the despatches to Sardinia, Agamemnon arrived at Naples in early September. There Nelson met Ferdinand VI, King of Naples, followed by the British ambassador to the kingdom, William Hamilton. At some point during the negotiations for reinforcements, Nelson was introduced to Hamilton's new wife, Emma Hamilton. The

negotiations were successful, and 2,000 men and several ships were

mustered by mid September. Nelson put to sea in pursuit of a French

frigate, but on failing to catch her, sailed for Leghorn, and then to Corsica. He

arrived at Toulon on 5 October, where he found that a large French army

had occupied the hills surrounding the city and was bombarding it. Hood

still hoped the city could be held if more reinforcements arrived, and

sent Nelson to join a squadron operating off Cagliari. Early on the morning of 22 October 1793, the Agamemnon sighted

five sails. Nelson closed with them, and discovered they were a French

squadron. Nelson promptly gave chase, firing on the 40-gun Melpomene. He

inflicted considerable damage but the remaining French ships turned to

join the battle and, realising he was outnumbered, Nelson withdrew and

continued to Cagliari, arriving on 24 October. After making repairs Nelson and the Agamemnon sailed again on 26 October, bound for Tunis with a squadron under Commodore Robert Linzee. On arrival, Nelson was given command of a small squadron consisting of the Agamemnon, three frigates and a sloop, and ordered to blockade the French garrison on Corsica. The

fall of Toulon at the end of December 1793 severely damaged British

fortunes in the Mediterranean. Hood had failed to make adequate

provision for a withdrawal and 18 French ships of the line fell into

republican hands. Nelson's mission to Corsica took on added significance, as it could provide the British a naval base close to the French coast. Hood therefore reinforced Nelson with extra ships during January 1794. A British assault force landed on the island on 7 February, after which Nelson moved to intensify the blockade off Bastia.

For the rest of the month he carried out raids along the coast and

intercepted enemy shipping. By late February St Fiorenzo had fallen and

British troops under Lieutenant - General David Dundas entered the outskirts of Bastia. However

Dundas merely assessed the enemy positions and then withdrew, arguing

the French were too well entrenched to risk an assault. Nelson

convinced Hood otherwise, but a protracted debate between the army and

naval commanders meant that Nelson did not receive permission to

proceed until late March. Nelson began to land guns from his ships and

emplace them in the hills surrounding the town. On 11 April the British

squadron entered the harbour and opened fire, whilst Nelson took

command of the land forces and commenced bombardment. After 45 days, the town surrendered. Nelson subsequently prepared for an assault on Calvi, working in company with Lieutenant - General Charles Stuart. British

forces landed at Calvi on 19 June, and immediately began moving guns

ashore to occupy the heights surrounding the town. While Nelson

directed a continuous bombardment of the enemy positions, Stuart's men

began to advance . On 12 July Nelson was at one of the forward

batteries early in the morning when a shot struck one of the sandbags

protecting the position, spraying stones and sand. Nelson was struck by

debris in his right eye and was forced to retire from the position,

although his wound was soon bandaged and he returned to action. By

18 July most of the enemy positions had been disabled, and that night

Stuart, supported by Nelson, stormed the main defensive position and

captured it. Repositioning their guns, the British brought Calvi under

constant bombardment, and the town surrendered on 10 August. However, Nelson's right eye had been irreparably damaged and he eventually lost sight in it. After the occupation of Corsica, Hood ordered Nelson to open diplomatic relations with the city-state of Genoa, a strategically important potential ally. Soon afterwards, Hood returned to England and was succeeded by Admiral William Hotham as commander - in - chief in the Mediterranean. Nelson put into Leghorn, and while the Agamemnon underwent

repairs, met with other naval officers at the port and entertained a

brief affair with a local woman, Adelaide Correglia. Hotham arrived with the rest of the fleet in December; Nelson and the Agamemnon sailed on a number of cruises with them in late 1794 and early 1795. On

8 March, news reached Hotham that the French fleet was at sea and

heading for Corsica. He immediately set out to intercept them, and

Nelson eagerly anticipated his first fleet action. The French were

reluctant to engage and the two fleets shadowed each other throughout

12 March. The following day two of the French ships collided, allowing

Nelson to engage the much larger 84-gun Ça Ira for

two and a half hours until the arrival of two French ships forced

Nelson to veer away, having inflicted heavy casualties and considerable damage. The fleets continued to shadow each other before making contact again, on 14 March, in the Battle of Genoa. Nelson joined the other British ships in attacking the battered Ça Ira, now under tow from the Censeur. Heavily damaged, the two French ships were forced to surrender and Nelson took possession of the Censeur. Defeated at sea, the French abandoned their plan to invade Corsica and returned to port. Nelson and the fleet remained in the Mediterranean throughout the summer. On 4 July the Agamemnon sailed

from St Fiorenzo with a small force of frigates and sloops, bound for

Genoa. On 6 July he ran into the French fleet and found himself pursued

by several much larger ships-of-the-line. He retreated to St Fiorenzo,

arriving just ahead of the pursuing French, who broke off as Nelson's

signal guns alerted the British fleet in the harbour. Hotham pursued the French to the Hyères Islands, but failed to bring them to a decisive action. A number of small engagements were fought but to Nelson's dismay, he saw little action. Nelson

returned to operate out of Genoa, intercepting and inspecting merchants

and cutting out suspicious vessels in both enemy and neutral harbours. He formulated ambitious plans for amphibious landings and naval assaults to frustrate the progress of the French Army of Italy that was now advancing on Genoa, but could excite little interest in Hotham. In November Hotham was replaced by Sir Hyde Parker but the situation in Italy was rapidly deteriorating: the French were raiding around Genoa and strong Jacobin sentiment was rife within the city itself. A

large French assault at the end of November broke the allied lines,

forcing a general retreat towards Genoa. Nelson's forces were able to

cover the withdrawing army and prevent them being surrounded, but he

had too few ships and men to materially alter the strategic situation,

and the British were forced to withdraw from the Italian ports. Nelson

returned to Corsica on 30 November, angry and depressed at the British

failure and questioning his future in the navy. In January 1796 the position of commander-in-chief of the fleet in the Mediterranean passed to Sir John Jervis, who appointed Nelson to exercise independent command over the ships blockading the French coast as a commodore. Nelson

spent the first half of the year conducting operations to frustrate

French advances and bolster Britain's Italian allies. Despite some

minor successes in intercepting small French warships, Nelson began to

feel the British presence on the Italian peninsula was rapidly becoming

useless. In June the Agamemnon was sent back to Britain for repairs, and Nelson was appointed to the 74-gun HMS Captain. In

the same month, the French thrust towards Leghorn and were certain to

capture the city. Nelson hurried there to oversee the evacuation of

British nationals and transported them to Corsica, after which Jervis

ordered him to blockade the newly captured French port. In July he oversaw the occupation of Elba, but by September the Genoese had broken their neutrality to declare in favour of the French. By October, the Genoese position and the continued French advances led the

British to decide that the Mediterranean fleet could no longer be

supplied; they ordered it to be evacuated to Gibraltar. Nelson helped

oversee the withdrawal from Corsica, and by December 1796 was aboard

the frigate HMS Minerve, covering the evacuation of the garrison at Elba. He then sailed for Gibraltar. During the passage, Nelson captured the Spanish frigate Santa Sabina and placed Lieutenants Jonathan Culverhouse and Thomas Hardy in charge of the captured vessel, taking the Spanish captain on board Minerve. Santa Sabina was

part of a larger Spanish force, and the following morning two Spanish

ships-of-the-line and a frigate were sighted closing fast. Unable to

outrun them Nelson initially determined to fight but Culverhouse and

Hardy raised the British colours and sailed northeast, drawing the

Spanish ships after them until being captured, giving Nelson the

opportunity to escape. Nelson went on to rendezvous with the British fleet at Elba, where he spent Christmas. He sailed for Gibraltar in late January, and after learning that the Spanish fleet had sailed from Cartagena, stopped just long enough to collect Hardy, Culverhouse, and the rest of the prize crew captured with Santa Sabina, before pressing on through the straits to join Sir John Jervis off Cadiz. Nelson joined Jervis's fleet off Cape St Vincent, and reported the Spanish movements. Jervis

decided to give battle and the two fleets met on 14 February. Nelson

found himself towards the rear of the British line and realised that it

would be a long time before he could bring Captain into action. Instead of continuing to follow the line, Nelson disobeyed orders and wore ship, breaking from the line and heading to engage the Spanish van, which consisted of the 112-gun San Josef, the 80-gun San Nicolas and the 130-gun Santísima Trinidad. Captain engaged all three, assisted by HMS Culloden which had come to Nelson's aid. After an hour of exchanging broadsides which left both Captain and Culloden heavily damaged, Nelson found himself alongside the San Nicolas. He led a boarding party across, crying "Westminster Abbey! or, glorious victory!" and forced her surrender. San Josef attempted to come to the San Nicolas’s aid, but became entangled with her compatriot and was left immobile. Nelson led his party from the deck of the San Nicolas onto the San Josef and captured her as well. As

night fell, the Spanish fleet broke off and sailed for Cadiz. Four

ships had surrendered to the British and two of them were Nelson's

captures. Nelson was victorious, but had disobeyed direct orders. Jervis liked Nelson and so did not officially reprimand him, but did not mention Nelson's actions in his official report of the battle. He did write a private letter to George Spencer in which he said that Nelson "contributed very much to the fortune of the day". Nelson

also wrote several letters about his victory, reporting that his action

was being referred to amongst the fleet as "Nelson's Patent Bridge for

boarding first rates". Nelson's account was later challenged by Rear - Admiral William Parker, who had been aboard HMS Prince George. Parker claimed that Nelson had been supported by several more ships than he acknowledged, and that the San Josef had already struck her colours by the time Nelson boarded her. Nelson's account of his role prevailed, and the victory was well received in Britain: Jervis was made Earl St Vincent and Nelson was made a Knight of the Bath. On 20 February, in a standard promotion according to his seniority and unrelated to the battle, he was promoted to Rear - Admiral of the Blue.

Nelson was given command of HMS Theseus in

the aftermath of the battle, and on 27 May 1797 was ordered to lie off

Cadiz, monitoring the Spanish fleet and awaiting the arrival of Spanish

treasure ships from the American colonies. He

carried out a bombardment and personally lead an amphibious assault on

3 July. During the action Nelson's barge collided with that of the

Spanish commander, and a hand to hand struggle ensued between the two

crews. Twice Nelson was nearly cut down and both times his life was

saved by a seaman named John Sykes who took the blows and was badly

wounded. The British raiding force captured the Spanish boat and towed

it back to the Theseus. During this period Nelson developed a scheme to capture Santa Cruz de Tenerife, aiming to seize a large quantity of specie from the treasure ship Principe de Asturias, which was reported to have recently arrived. The

battle plan called for a combination of naval bombardments and an

amphibious landing. The initial attempt was called off after adverse

currents hampered the assault and the element of surprise was lost. Nelson

immediately ordered another assault but this was beaten back. He

prepared for a third attempt, to take place during the night. Although

he personally led one of the battalions, the operation ended in

failure: the Spanish were better prepared than had been expected and

had secured strong defensive positions. Several of the boats failed to land at the correct positions in the confusion,

while those that did were swept by gunfire and grapeshot. Nelson's boat

reached its intended landing point but as he stepped ashore he was hit

in the right arm by a musketball, which fractured his humerus bone in multiple places. He was rowed back to the Theseus to

be attended to by the surgeon. On arriving on his ship he refused to be

helped aboard, declaring "Let me alone! I have got my legs left and one

arm." He was taken to the surgeon, instructing him to prepare his instruments and "the sooner it was off the better". Most of the right arm was amputated and within half an hour Nelson had returned to issuing orders to his captains. Years later he would excuse himself to Commodore John Thomas Duckworth for not writing longer letters due to not being naturally left-handed. Meanwhile a force under Sir Thomas Troubridge had

fought their way to the main square but could go no further. Unable to

return to the fleet because their boats had been sunk, Troubridge was

forced to enter into negotiations with the Spanish commander, and the

British were subsequently allowed to withdraw. The expedition had failed to achieve any of its objectives and had left a quarter of the landing force dead or wounded. The

squadron remained off Tenerife for a further three days and by 16

August had rejoined Jervis's fleet off Cadiz. Despondently Nelson wrote

to Jervis: "A left-handed Admiral will never again be considered as

useful, therefore the sooner I get to a very humble cottage the better,

and make room for a better man to serve the state". He returned to England aboard HMS Seahorse, arriving at Spithead on

1 September. He was met with a hero's welcome: the British public had

lionised Nelson after Cape St Vincent and his wound earned him sympathy. They

refused to attribute the defeat at Tenerife to him, preferring instead

to blame poor planning on the part of St Vincent, the Secretary at War or even William Pitt. Nelson

returned to Bath with Fanny, before moving to London in October to seek

expert medical attention concerning his amputated arm. Whilst in London

news reached him that Admiral Duncan had defeated the Dutch fleet at the Battle of Camperdown. Nelson exclaimed that he would have given his other arm to have been present. He

spent the last months of 1797 recuperating in London, during which he

was awarded the Freedom of the City of London and an annual pension of

£1,000 a year. He used the money to buy Round Wood Farm near Ipswich, and intended to retire there with Fanny. Despite his plans, Nelson was never to live there. Although surgeons had been unable to remove the central ligature in

his amputated arm, which had caused considerable inflammation and

poisoning, in early December it came out of its own accord and Nelson

rapidly began to recover. Eager to return to sea, he began agitating

for a command and was promised the 80-gun HMS Foudroyant. As she was not yet ready for sea, Nelson was instead given command of the 74-gun HMS Vanguard, to which he appointed Edward Berry as his flag captain. French

activities in the Mediterranean theatre were raising concern among the

Admiralty: Napoleon was gathering forces in Southern France but the

destination of his army was unknown. Nelson and the Vanguard were

to be despatched to Cadiz to reinforce the fleet. On 28 March 1798,

Nelson hoisted his flag and sailed to join Earl St Vincent. St Vincent

sent him on to Gibraltar with a small force to reconnoitre French

activities. While Nelson was sailing to Gibraltar through a fierce storm, Napoleon had sailed with his invasion fleet under the command of Vice - admiral François-Paul Brueys d'Aigalliers.

When news of the French departure reached St Vincent, Nelson was

reinforced with a number of ships and ordered to intercept the French. Nelson

immediately began searching the Italian coast for Napoleon's fleet, but

was hampered by a lack of frigates that could operate as fast scouts.

Napoleon had already arrived at Malta and, after a show of force, secured the island's surrender. Nelson

followed him there, but the French had already left. After a conference

with his captains, he decided Egypt was Napoleon's most likely

destination and headed for Alexandria.

On his arrival on 28 June, though, he found no sign of the French;

dismayed, he withdrew and began searching to the east of the port.

While he was absent, Napoleon's fleet arrived on 1 July and landed

their forces unopposed. Brueys then anchored his fleet in Aboukir Bay, ready to support Napoleon if required. Nelson

meanwhile had crossed the Mediterranean again in a fruitless attempt to

locate the French and had returned to Naples to re-provision. He sailed again, intending to search the seas off Cyprus,

but decided to pass Alexandria again for a final check. In doing so his

force captured a French merchant, which provided the first news of the

French fleet: they had passed south-east of Crete a month before,

heading to Alexandria. Nelson

hurried to the port but again found it empty of the French. Searching

along the coast, he finally discovered the French fleet in Aboukir Bay

on 1 August 1798.

Nelson

immediately prepared for battle, repeating a sentiment he had expressed

at the battle of Cape St. Vincent that "Before this time tomorrow, I

shall have gained a peerage or Westminster Abbey." It

was late by the time the British arrived and the French, anchored in a

strong position with a combined fire power greater than that of

Nelson's fleet, did not expect them to attack. Nelson

however immediately ordered his ships to advance. The French line was

anchored close to a line of shoals, in the belief that this would secure their port side from attack; Brueys had assumed the British would follow convention and attack his centre from the starboard side. However, Captain Thomas Foley aboard HMS Goliath discovered a gap between the shoals and the French ships, and took Goliath into

the channel. The unprepared French found themselves attacked on both

sides, the British fleet splitting, with some following Foley and

others passing down the starboard side of the French line. The British fleet was soon heavily engaged, passing down the French line and engaging their ships one by one. Nelson on Vanguard personally engaged Spartiate, also coming under fire from Aquilon.

At about eight o'clock, he was with Berry on the quarter-deck when a

piece of French shot struck him in his forehead. He fell to the deck, a

flap of torn skin obscuring his good eye. Blinded and half stunned, he

felt sure he would die and cried out "I am killed. Remember me to my

wife." He was taken below to be seen by the surgeon. After examining Nelson, the surgeon pronounced the wound non-threatening and applied a temporary bandage. The

French van, pounded by British fire from both sides, had begun to

surrender, and the victorious British ships continued to move down the

line, bringing Brueys's 118-gun flagship Orient under constant heavy fire. Orient caught

fire under this bombardment, and later exploded. Nelson briefly came on

deck to direct the battle, but returned to the surgeon after watching

the destruction of Orient. The Battle of the Nile was a major blow to Napoleon's ambitions in the east. The fleet had been destroyed: Orient,

another ship and two frigates had been burnt, seven 74-gun ships and

two 80-gun ships had been captured, and only two ships-of-the-line and

two frigates escaped, while the forces Napoleon had brought to Egypt were stranded. Napoleon attacked north along the Mediterranean coast, but Turkish defenders supported by Captain Sir Sidney Smith defeated his army at the Siege of Acre.

Napoleon then left his army and sailed back to France, evading

detection by British ships. Given its strategic importance, some

historians regard Nelson's achievement at the Nile as the most

significant of his career, even greater than that at Trafalgar seven

years later.

Nelson wrote despatches to the Admiralty and oversaw temporary repairs to the Vanguard, before sailing to Naples where he was met with enthusiastic celebrations. The

King of Naples, in company with the Hamiltons, greeted him in person

when he arrived at the port and William Hamilton invited Nelson to stay

at their house. Celebrations

were held in honour of Nelson's birthday that September, and he

attended a banquet at the Hamilton's, where other officers had begun to

notice his attention to Emma. Jervis himself had begun to grow

concerned about reports of Nelson's behaviour, but in early October

word of Nelson's victory had reached London. The First Lord of the

Admiralty, Earl Spencer, fainted on hearing the news. Scenes

of celebration erupted across the country, balls and victory feasts

were held and church bells were rung. The City of London awarded Nelson

and his captains with swords, whilst the King ordered them to be

presented with special medals. The Tsar of Russia sent him a gift, and Selim III,

the Sultan of Turkey, awarded Nelson the Order of the Turkish Crescent

for his role in restoring Ottoman rule in Egypt. Lord Hood, after a

conversation with the Prime Minister, told Fanny that Nelson would likely be given a Viscountcy, similar to Jervis's earldom after Cape St Vincent and Duncan's viscountcy after Camperdown. Earl

Spencer however demurred, arguing that as Nelson had only been detached

in command of a squadron, rather than being the commander in chief of

the fleet, such an award would create an unwelcome precedent. Instead,

Nelson received the title Baron Nelson of the Nile. Nelson was dismayed by Spencer's decision, and declared that he would rather have received no title than that of a mere barony. He

was however cheered by the attention showered on him by the citizens of

Naples, the prestige accorded him by the kingdom's elite, and the

comforts he received at the Hamiltons' residence. He made frequent

visits to attend functions in his honour, or to tour nearby attractions

with Emma, with whom he had by now fallen deeply in love, almost

constantly at his side. Orders

arrived from the Admiralty to blockade the French forces in Alexandria

and Malta, a task Nelson delegated to his captains, Samuel Hood and Alexander Ball. Despite enjoying his lifestyle in Naples Nelson began to think of returning to England, but King Ferdinand of Naples, after a long period of pressure from his wife Maria Carolina of Austria and Sir William Hamilton, finally agreed to declare war on France. The Neapolitan army, led by the Austrian General Mack and supported by Nelson's fleet, retook Rome from

the French in late November, but the French regrouped outside the city

and, after being reinforced, routed the Neapolitans. In disarray, the

Neapolitan army fled back to Naples, with the pursuing French close

behind. Nelson

hastily organised the evacuation of the Royal Family, several nobles

and the British nationals, including the Hamiltons. The evacuation got

underway on 23 December and sailed through heavy gales before reaching

the safety of Palermo on 26 December. With

the departure of the Royal Family, Naples descended into anarchy and

news reached Palermo in January that the French had entered the city

under General Championnet and proclaimed the Parthenopaean Republic. Nelson was promoted to Rear Admiral of the Red on 14 February 1799, and was occupied for several months in blockading Naples, while a popular counter revolutionary force under Cardinal Ruffo known as the Sanfedisti marched

to retake the city. In late June Ruffo's army entered Naples, forcing

the French and their supporters to withdraw to the city's

fortifications as rioting and looting broke out amongst the

ill-disciplined Neapolitan troops. Dismayed

by the bloodshed, Ruffo agreed to a general amnesty with the Jacobin

forces that allowed them safe conduct to France. Nelson, now aboard the Foudroyant, was outraged, and backed by King Ferdinand he insisted that the rebels must surrender unconditionally. He took those who had surrendered under the amnesty under armed guard, including the former Admiral Francesco Caracciolo, who had commanded the Neapolitan navy under King Ferdinand but had changed sides during the brief Jacobin rule. Nelson

ordered his trial by court-martial and refused Caracciolo's request

that it be held by British officers. Caracciolo was tried by royalist

Neapolitan officers and sentenced to death. He asked to be shot rather

than hanged, but Nelson also refused this request and ignored the

court's request to allow 24 hours for Caracciolo to prepare

himself. Caracciolo was hanged aboard the Neapolitan frigate Minerva at 5 o'clock the same afternoon. Nelson

kept the Jacobins imprisoned and approved of a wave of further

executions, refusing to intervene despite pleas for clemency from the

Hamiltons and the Queen of Naples. When transports were finally allowed to carry the Jacobins to France, less than a third were still alive. For his support of the monarchy Nelson was made Duke of Bronte by King Ferdinand. Nelson returned to Palermo in August and in September became the senior officer in the Mediterranean after Jervis' successor Lord Keith left to chase the French and Spanish fleets into the Atlantic. Nelson

spent the rest of 1799 at the Neapolitan court but put to sea again in

February 1800 after Lord Keith's return. On 18 February Généreux, a survivor of the Nile, was sighted and Nelson gave chase, capturing her after a short battle and winning Keith's approval. Nelson

had a difficult relationship with his superior officer: he was gaining

a reputation for insubordination, having initially refused to send

ships when Keith requested them and on occasion returning to Palermo

without orders, pleading poor health. Keith's

reports, and rumours of Nelson's close relationship with Emma Hamilton,

were also circulating in London, and Earl Spencer wrote a pointed

letter suggesting that he return home: You

will be more likely to recover your health and strength in England than

in any inactive situation at a foreign Court, however pleasing the

respect and gratitude shown to you for your services may be. The

recall of Sir William Hamilton to Britain was a further incentive for

Nelson to return, although he and the Hamiltons initially sailed from Naples on a brief cruise around Malta aboard the Foudroyant in April 1800. It was on this voyage that Horatio and Emma's illegitimate daughter Horatia was probably conceived. After the cruise, Nelson conveyed the Queen of Naples and her suite to Leghorn. On his arrival, Nelson shifted his flag to HMS Alexander,

but again disobeyed Keith's orders by refusing to join the main fleet.

Keith came to Leghorn in person to demand an explanation, and refused

to be moved by the Queen's pleas to allow her to be conveyed in a

British ship. In

the face of Keith's demands, Nelson reluctantly struck his flag and

bowed to Emma Hamilton's request to return to England by land. Nelson, the Hamiltons and several other British travellers left Leghorn for Florence on 13 July. They made stops at Trieste and Vienna, spending three weeks in the latter where they were entertained by the local nobility and heard the Missa in Angustiis by Haydn that now bears Nelson's name. By September they were in Prague, and later called at Dresden, Dessau and Hamburg, from where they caught a packet ship to Great Yarmouth, arriving on 6 November. Nelson

was given a hero's welcome and after being sworn in as a freeman of the

borough and received the massed crowd's applause. He subsequently made

his way to London, arriving on 9 November. He attended court and was

guest of honour at a number of banquets and balls. It was during this

period that Fanny Nelson and Emma Hamilton met for the first time.

During this period, Nelson was reported as being cold and distant to

his wife and his attention to Emma became the subject of gossip. With

the marriage breaking down, Nelson began to hate even being in the same

room as Fanny. Events came to a head around Christmas, when according

to Nelson's solicitor, Fanny issued an ultimatum on whether he was to

choose her or Emma. Nelson replied: I

love you sincerely but I cannot forget my obligations to Lady Hamilton

or speak of her otherwise than with affection and admiration. The two never lived together again after this.

Shortly after his arrival in England Nelson was appointed to be second-in-command of the Channel Fleet under Lord St Vincent. He was promoted to Vice Admiral of the Blue on 1 January 1801, and travelled to Plymouth, where on 22 January he was granted the freedom of the city, and on 29 January Emma gave birth to their daughter, Horatia. Nelson was delighted, but subsequently disappointed when he was instructed to move his flag from HMS San Josef to HMS St George in preparation for a planned expedition to the Baltic. Tired

of British ships imposing a blockade against French trade and stopping

and searching their merchants, the Russian, Prussian, Danish and

Swedish governments had formed an alliance to break the blockade.

Nelson joined Admiral Sir Hyde Parker's

fleet at Yarmouth, from where they sailed for the Danish coast in

March. On their arrival Parker was inclined to blockade the Danish and

control the entrance to the Baltic, but Nelson urged a pre-emptive

attack on the Danish fleet at harbour in Copenhagen. He convinced Parker to allow him to make an assault, and was given significant reinforcements. Parker himself would wait in the Kattegat, covering Nelson's fleet in case of the arrival of the Swedish or Russian fleets. On

the morning of 2 April 1801, Nelson began to advance into Copenhagen

harbour. The battle began badly for the British, with HMS Agamemnon, HMS Bellona and HMS Russell running

aground, and the rest of the fleet encountering heavier fire from the

Danish shore batteries than had been anticipated. Parker sent the

signal for Nelson to withdraw, reasoning: I

will make the signal for recall for Nelson's sake. If he is in a

condition to continue the action he will disregard it; if he is not, it

will be an excuse for his retreat and no blame can be attached to him. Nelson, directing action aboard HMS Elephant,

was informed of the signal by the signal lieutenant, Frederick

Langford, but angrily responded: 'I told you to look out on the Danish

commodore and let me know when he surrendered. Keep your eyes fixed on

him.' He then turned to his flag captain, Thomas Foley and

said 'You know, Foley, I have only one eye. I have a right to be blind

sometimes.' He raised the telescope to his blind eye, and said 'I

really do not see the signal.' The

battle lasted three hours, leaving both Danish and British fleets

heavily damaged. At length Nelson despatched a letter to the Danish

commander, Crown Prince Frederick calling for a truce, which the Prince accepted. Parker

approved of Nelson's actions in retrospect, and Nelson was given the

honour of going into Copenhagen the next day to open formal

negotiations. At a banquet that evening he told Prince Frederick that the battle had been the most severe he had ever been in. The

outcome of the battle and several weeks of ensuing negotiations was a

14 week armistice, and on Parker's recall in May, Nelson became

commander-in-chief in the Baltic Sea. As

a reward for the victory, he was created Viscount Nelson of the Nile

and of Burnham Thorpe in the County of Norfolk, on 19 May 1801. In

addition, on 4 August 1801, he was created Baron Nelson, of the Nile

and of Hilborough in the County of Norfolk, this time with a special

remainder to his father and sisters. Nelson subsequently sailed to the Russian naval base at Reval in

May, and there learned that the pact of armed neutrality was to be

disbanded. Satisfied with the outcome of the expedition, he returned to

England, arriving on 1 July.

In France, Napoleon was massing forces to invade Great Britain. After a brief spell in London, where he again visited the Hamiltons, Nelson was placed in charge of defending the English Channel to prevent the invasion. He spent the summer reconnoitring the French coast, but apart from a failed attack on Boulogne in August, saw little action. On 22 October 1801 the Peace of Amiens was

signed between the British and the French, and Nelson – in poor health

again – retired to Britain where he stayed with Sir William and Lady

Hamilton. On 30 October Nelson spoke in support of the Addington government in the House of Lords, and afterwards made regular visits to attend sessions. The three embarked on a tour of England and Wales, visiting Birmingham, Warwick, Gloucester, Swansea, Monmouth and

numerous other towns and villages. Nelson often found himself received

as a hero and was the centre of celebrations and events held in his

honour. In 1802, Nelson bought Merton Place, a country estate in Merton, Surrey (now south-west London) where he lived briefly with the Hamiltons until William's death in April 1803. The following month, war broke out again and Nelson prepared to return to sea. Nelson was appointed commander-in-chief of the Mediterranean Fleet and given the first-rate HMS Victory as

his flagship. He joined her at Portsmouth, where he received orders to

sail to Malta and take command of a squadron there before joining the

blockade of Toulon. Nelson arrived off Toulon in July 1803 and spent the next year and a half enforcing the blockade. He was promoted to Vice Admiral of the White while still at sea, on 23 April 1804. In January 1805 the French fleet, under Admiral Pierre-Charles Villeneuve,

escaped Toulon and eluded the blockading British. Nelson set off in

pursuit but after searching the eastern Mediterranean he learned that the French had been blown back into Toulon. Villeneuve managed to break out a second time in April, and this time succeeded in passing through the Strait of Gibraltar and into the Atlantic, bound for the West Indies. Nelson

gave chase, but after arriving in the Caribbean spent June in a

fruitless search for the fleet. Villeneuve had briefly cruised around

the islands before heading back to Europe, in contravention of

Napoleon's orders. The returning French fleet was intercepted by a British fleet under Sir Robert Calder and engaged in the Battle of Cape Finisterre, but managed to reach Ferrol with only minor losses. Nelson

returned to Gibraltar at the end of July, and travelled from there to

England, dismayed at his failure to bring the French to battle and

expecting to be censured. To

his surprise he was given a rapturous reception from crowds who had

gathered to view his arrival, while senior British officials

congratulated him for sustaining the close pursuit and credited him for

saving the West Indies from a French invasion. Nelson

briefly stayed in London, where he was cheered wherever he went, before

visiting Merton to see Emma, arriving in late August. He entertained a

number of his friends and relations there over the coming month, and

began plans for a grand engagement with the enemy fleet, one that would

surprise his foes by forcing a pell-mell battle on them. Captain Henry Blackwood arrived

at Merton early on 2 September, bringing news that the French and

Spanish fleets had combined and were currently at anchor in Cádiz. Nelson hurried to London where he met with cabinet ministers and was given command of the fleet blockading Cádiz. Nelson

returned briefly to Merton to set his affairs in order and bid farewell

to Emma, before travelling back to London and then on to Portsmouth,

arriving there early in the morning of 14 September. He breakfasted at

the George Inn with his friends George Rose, the Vice President of the Board of Trade, and George Canning, the Treasurer of the Navy.

During the breakfast word spread of Nelson's presence at the inn and a

large crowd of well wishers gathered. They accompanied Nelson to his

barge and cheered him off, which Nelson acknowledged by raising his

hat. Nelson was recorded as having turned to his colleague and stated,

"I had their huzzas before: I have their hearts now". Robert Southey reported

that of the onlookers for Nelson's walk to the dock, "Many were in

tears and many knelt down before him and blessed him as he passed". Victory joined the British fleet off Cádiz on 27 September, Nelson taking over from Rear-Admiral Collingwood. He

spent the following weeks preparing and refining his tactics for the

anticipated battle and dining with his captains to ensure they

understood his intentions. Nelson had devised a plan of attack that anticipated the allied fleet would form up in a traditional line of battle. Drawing on his own experience from the Nile and Copenhagen, and the examples of Duncan at Camperdown and Rodney at the Saintes, Nelson decided to split his fleet into squadrons rather than forming it into a similar line parallel to the enemy. These

squadrons would then cut the enemy's line in a number of places,

allowing a pell-mell battle to develop in which the British ships could

overwhelm and destroy parts of their opponents' formation, before the

unengaged enemy ships could come to their aid.

The

combined French and Spanish fleet under Villeneuve's command numbered

33 ships of the line. Napoleon Bonaparte had intended for Villeneuve to

sail into the English Channel and

cover the planned invasion of Britain, but the entry of Austria and

Russia into the war forced Napoleon to call off the planned invasion

and transfer troops to Germany. Villeneuve had been reluctant to risk

an engagement with the British, and this reluctance led Napoleon to

order Vice-Admiral François Rosily to

go to Cádiz and take command of the fleet, sail it into the

Mediterranean to land troops at Naples, before making port at Toulon. Villeneuve decided to sail the fleet out before his successor arrived. On

20 October the fleet was sighted making its way out of harbour by

patrolling British frigates, and Nelson was informed that they appeared

to be headed to the west. At four o'clock in the morning of 21 October Nelson ordered the Victory to

turn towards the approaching enemy fleet, and signalled the rest of his

force to battle stations. He then went below and made his will, before

returning to the quarterdeck to carry out an inspection. Despite

having 27 ships to Villeneuve's 33, Nelson was confident of success,

declaring that he would not be satisfied with taking fewer than 20

prizes. He returned briefly to his cabin to write a final prayer, after which he joined Victory’s signal lieutenant, John Pasco. Mr

Pasco, I wish to say to the fleet "England confides that every man will

do his duty". You must be quick, for I have one more signal to make,

which is for close action. Pasco

suggested changing 'confides' to 'expects', which being in the Signal

Book, could be signalled by the use of a single flag, whereas

'confides' would have to spelt out letter by letter. Nelson agreed, and the signal was hoisted. As the fleets converged, the Victory’s

captain, Thomas Hardy suggested that Nelson remove the decorations on

his coat, so that he would not be so easily identified by enemy

sharpshooters. Nelson replied that it was too late 'to be shifting a

coat', adding that they were 'military orders and he did not fear to

show them to the enemy'. Captain Henry Blackwood, of the frigate HMS Euryalus,

suggested Nelson come aboard his ship to better observe the battle.

Nelson refused, and also turned down Hardy's suggestion to let Eliab Harvey's HMS Temeraire come ahead of the Victory and lead the line into battle.

Victory came

under fire, initially passing wide, but then with greater accuracy as

the distances decreased. A cannon ball struck and killed Nelson's

secretary, John Scott, nearly cutting him in two. Hardy's clerk took

over, but he too was almost immediately killed. Victory’s wheel was shot away, and another cannon ball cut down eight marines.

Hardy, standing next to Nelson on the quarterdeck, had his shoe buckle

dented by a splinter. Nelson observed 'this is too warm work to last

long'. The Victory had

by now reached the enemy line, and Hardy asked Nelson which ship to

engage first. Nelson told him to take his pick, and Hardy moved Victory across the stern of the 80-gun French flagship Bucentaure. Victory then came under fire from the 74-gun Redoutable, lying off the Bucentaure’s stern, and the 130-gun Santísima Trinidad. As snipers from the enemy ships fired onto Victory’s deck from their rigging, Nelson and Hardy continued to walk about, directing and giving orders. Shortly

after one o'clock, Hardy realised that Nelson was not by his side. He

turned to see Nelson kneeling on the deck, supporting himself with his

hand, before falling onto his side. Hardy rushed to him, at which point

Nelson smiled Hardy, I do believe they have done it at last... my backbone is shot through. He had been hit by a marksman from the Redoutable,

firing at a range of 50 feet. The bullet had entered his left

shoulder, pierced his lung, and come to rest at the base of his spine. Nelson

was carried below by a sergeant - major of marines and two seamen. As he

was being carried down, he asked them to pause while he gave some

advice to a midshipman on the handling of the tiller. He then draped a handkerchief over his face to avoid causing alarm amongst the crew. He was taken to the surgeon William Beatty, telling him: "You can do nothing for me. I have but a short time to live. My back is shot through." Nelson

was made comfortable, fanned and brought lemonade and watered wine to

drink after he complained of feeling hot and thirsty. He asked several

times to see Hardy, who was on deck supervising the battle, and asked

Beatty to remember him to Emma, his daughter and his friends.

Hardy

came below deck to see Nelson just after half-past two, and informed

him that a number of enemy ships had surrendered. Nelson told him that

he was sure to die, and begged him to pass his possessions to Emma. With Nelson at this point were the chaplain Alexander Scott,

the purser Walter Burke, Nelson's steward, Chevalier, and Beatty.

Nelson, fearing that a gale was blowing up, instructed Hardy to be sure

to anchor. After reminding him to 'take care of poor Lady Hamilton',

Nelson said 'Kiss me, Hardy'. Beatty recorded that Hardy knelt and kissed Nelson on the cheek. He then stood

for a minute or two and then kissed him again. Nelson asked 'Who is

that?', and on hearing that it was Hardy, replied 'God bless you Hardy.' By

now very weak, Nelson continued to murmur instructions to Burke and

Scott, 'fan, fan ... rub, rub ... drink, drink.' Beatty heard

Nelson murmur 'Thank God I have done my duty' and when he returned,

Nelson's voice had faded and his pulse was very weak. He

looked up as Beatty took his pulse, then closed his eyes. Scott, who

remained by Nelson as he died, recorded his last words as 'God and my

country'. Nelson died at half past four, three hours after he was shot. Nelson's body was placed in a cask of brandy mixed with camphor and myrrh, which was then lashed to the Victory’s main mast and placed under guard. Victory was towed to Gibraltar after the battle, and on arrival the body was transferred to a lead-lined coffin filled with spirits of wine. Collingwood's dispatches about the battle were carried to England aboard HMS Pickle,

and when the news arrived in London, a messenger was sent to Merton

Place to bring the news of Nelson's death to Emma Hamilton. She later

recalled They

brought me word, Mr Whitby from the Admiralty. 'Show him in directly,'

I said. He came in, and with a pale countenance and faint voice, said,

'We have gained a great Victory.' - 'Never mind your Victory,' I said.

'My letters - give me my letters' - Captain Whitby was unable to speak

- tears in his eyes and a deathly paleness over his face made me

comprehend him. I believe I gave a scream and fell back, and for ten

hours I could neither speak nor shed a tear. King George III, on receiving the news, is alleged to have said, in tears, "We have lost more than we have gained." The Times reported We

do not know whether we should mourn or rejoice. The country has gained

the most splendid and decisive Victory that has ever graced the naval

annals of England; but it has been dearly purchased. The first tribute to Nelson was fittingly offered at sea by sailors of Vice - Admiral Dmitry Senyavin's passing Russian squadron, which saluted on learning of the death.

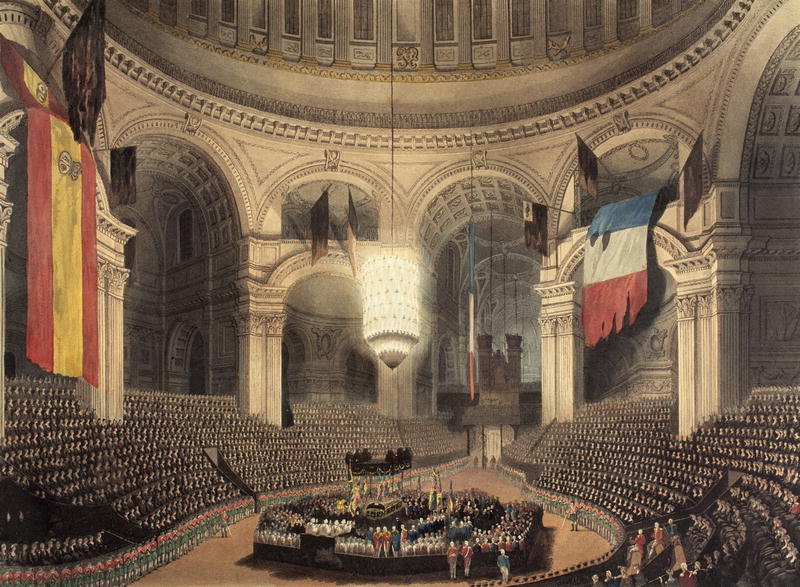

Nelson's pickled corpse was moved from the HMS Pickle to the Victory. Unloaded at the Nore it was taken to Greenwich and placed in a lead coffin, and that in another wooden one, made from the mast of L'Orient which had been salvaged after the Battle of the Nile. He lay in state in the Painted Hall at Greenwich for three days, before being taken up river aboard a barge, accompanied by Lord Hood, Sir Peter Parker, and the Prince of Wales. The

Prince of Wales at first announced his intention to attend the funeral

as chief mourner, but later attended in a private capacity with his

brothers when his father George III reminded him that it was against

protocol for the Heir to the Throne to attend the funerals of anyone

except members of the Royal Family. The coffin was taken into the Admiralty for the night, attended by Nelson's chaplain, Alexander Scott. The

next day, 9 January, a funeral procession consisting of 32 admirals,

over a hundred captains, and an escort of 10,000 troops took the coffin

from the Admiralty to St. Paul's Cathedral. After a four hour service he was laid to rest within a sarcophagus originally carved for Cardinal Wolsey. Nelson

was regarded as a highly effective leader, and someone who was able to

sympathise with the needs of his men. He based his command on love

rather than authority, inspiring both his superiors and his

subordinates with his considerable courage, commitment and charisma,

dubbed 'the Nelson touch'. Nelson

combined this talent with an adept grasp of strategy and politics,

making him a highly successful naval commander. However, Nelson's

personality was complex, often characterised by a desire to be noticed,

both by his superiors, and the general public. He was easily flattered

by praise, and dismayed when he felt he was not given sufficient credit

for his actions. This led him to take risks, and to enthusiastically publicise his resultant successes. Nelson was also highly confident in his abilities, determined and able to make important decisions. His

active career meant that he was considerably experienced in combat, and

was a shrewd judge of his opponents, able to identify and exploit his

enemies' weaknesses. He was often prone to insecurities however, as well as violent mood swings, and was extremely vain: he loved to receive decorations, tributes and praise. Despite his personality, he remained a highly professional leader and was driven all his life by a strong sense of duty. Nelson's

fame reached new heights after his death, and he came to be regarded as

one of Britain's greatest military heroes, ranked alongside the Duke of Marlborough and the Duke of Wellington. In the BBC's 100 Greatest Britons programme in 2002, Nelson was voted the ninth greatest Briton of all time. Aspects

of Nelson's life and career were controversial, both during his

lifetime and after his death. His affair with Emma Hamilton was widely

remarked upon and disapproved of, to the extent that Emma was denied

permission to attend Nelson's funeral and was subsequently ignored by

the government, which awarded money and titles to Nelson's legitimate

family. Nelson's

actions during the reoccupation of Naples have also been the subject of

debate: his approval of the wave of reprisals against the Jacobins who had surrendered under the terms agreed by Cardinal Ruffo, and his personal intervention in securing the execution of Caracciolo, are considered by some biographers, such as Robert Southey, to have been a shameful breach of honour. Prominent contemporary politician Charles James Fox was among those who attacked Nelson for his actions at Naples, declaring in the House of Commons I

wish that the atrocities of which we hear so much and which I abhor as

much as any man, were indeed unexampled. I fear that they do not belong

exclusively to the French ... Naples for instance has been what is

called "delivered", and yet, if I am rightly informed, it has been

stained and polluted by murders so ferocious, and by cruelties of every

kind so abhorrent, that the heart shudders at the recital ... [The

besieged rebels] demanded that a British officer should be brought

forward, and to him they capitulated. They made terms with him under

the sanction of the British name ... Before they sailed their property

was confiscated, numbers ... were thrown into dungeons, and some of

them, I understand, notwithstanding the British guarantee, were

actually executed. Other pro-republican writers produced books and pamphlets decrying the events in Naples as atrocities. Later assessments, including one by Andrew Lambert,

have stressed that the armistice had not been authorised by the King of

Naples, and that the retribution meted out by the Neapolitans was not

unusual for the time. Lambert also suggests that Nelson in fact acted

to put an end to the bloodshed, using his ships and men to restore

order in the city. Nelson's

influence continued long after his death, and saw periodic revivals of

interest, especially during times of crisis in Britain. In the 1860s Poet Laureate Alfred Tennyson appealed to the image and tradition of Nelson, in order to oppose the defence cuts being made by Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone. First Sea Lord Jackie Fisher was

a keen exponent of Nelson during the early years of the twentieth

century, and often emphasised his legacy during his period of naval

reform. Winston Churchill also found Nelson to be a source of inspiration during the Second World War. Nelson has been frequently depicted in art and literature; he appeared in paintings by Benjamin West and Arthur William Devis, and in books and biographies by John McArthur, James Stanier Clarke and Robert Southey. A

number of monuments and memorials were constructed across the country

to honour his memory and achievements, with work beginning on Dublin's monument to Nelson, Nelson's Pillar, in 1808. In Montreal, a statue was started in 1808 and completed in 1809. Others followed around the world, with London's Trafalgar Square being created in his memory in 1835 and the centrepiece, Nelson's Column, finished in 1843.