<Back to Index>

- Biologist Gregory Goodwin Pincus, 1903

- Bluesman Mance Lipscomb, 1895

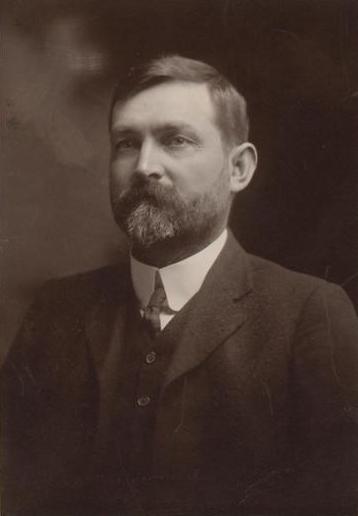

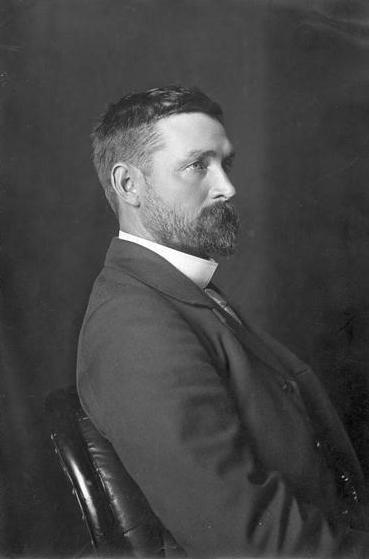

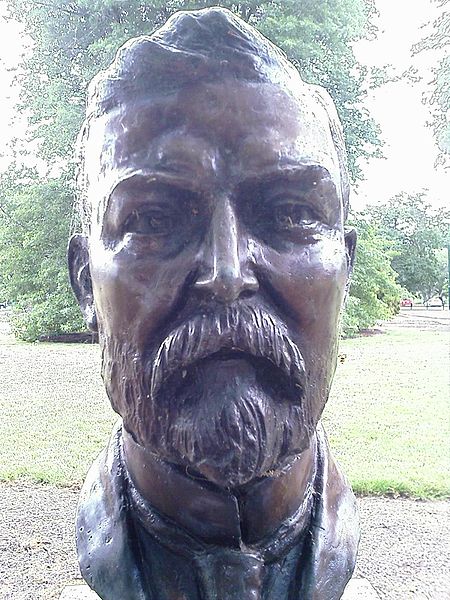

- 3rd Prime Minister of Australia John Christian "Chris" Watson, 1867

PAGE SPONSOR

John Christian Watson (9 April 1867 – 18 November 1941), commonly known as Chris Watson, Australian politician, was the third Prime Minister of Australia. He was the first prime minister from the Australian Labour Party (the spelling of 'Labour' was changed to 'Labor' in 1912), and the first Labour Party prime minister in the world.

He was elected to parliament at the first federal election in March 1901. The Caucus chose

him as the inaugural parliamentary leader of the Labour Party on 8 May

1901, just in time for the first meeting of parliament. His term as

Prime Minister was brief - only four months, between 27 April and 18

August 1904, but his party did hold the balance of power, giving support to Protectionist Party legislation in exchange for concessions to enact the Labour Party policy platform. He retired from Parliament in 1907. According to Percival Serle,

Watson "left a much greater impression on his time than this would

suggest. He came at the right moment for his party, and nothing could

have done it more good than the sincerity, courtesy and moderation

which he always showed as a leader". Alfred Deakin wrote

of Watson: "The Labour section has much cause for gratitude to Mr

Watson, the leader whose tact and judgement have enabled it to achieve

many of its Parliamentary successes". Watson

maintained that his father was a British seaman called George Watson.

Records dispute this, however; they indicate that Watson's father was a Chilean citizen of German descent, Johan Cristian Tanck, and that Watson was born in Valparaíso, Chile. Records also show his mother was a New Zealander, Martha Minchin, who had married Tanck in New Zealand and

then gone to sea with him. In 1868 his parents separated, and in 1869

she married George Watson, whose name young Chris then took. None of

these facts became known until after Watson's death. Watson went to school in Oamaru, New Zealand, and at 13 was apprenticed as a printer. In 1886 he moved to Sydney to

better his prospects. He found work as an editor for several

newspapers. Through this proximity to newspapers, books and writers he

furthered his education and developed an interest in politics. In

1889 he married Ada Jane Low, an English-born Sydney seamstress.

Nothing is known about her previous life and no photograph of her has

been found. Watson

was a founding member of the New South Wales Labor Party in 1891. He

was an active trade unionist, and became Vice - President of the Sydney Trades and Labour Council in

January 1892. In June 1892, he settled a dispute between the TLC and

the Labor Party and as a result became the president of the council and

chairman of the party. In 1893 and 1894, he worked hard to resolve the

debate over the solidarity pledge and established the Labor Party's

basic practices, including the sovereignty of the party conference,

caucus solidarity, the pledge required of parliamentarians and the

powerful role of the extra - parliamentary executive. In 1894 Watson

was

elected to the New South Wales Legislative Assembly for the country seat of Young. Labor at this time had a policy of "support in return for concessions," and Watson voted with his colleagues to keep the Free Trade Premier, Sir George Reid, in office. After the 1898 election, Watson and Labor leader James McGowen decided to keep the Reid government in office so that it could complete the work of establishing Federation. Watson

assisted to shape party policy regarding the movement for federation

from 1895, and was one of ten Labour candidates nominated for the

Australasian Federal Convention on 4 March 1897, however none were

elected. The party, perforce, endorsed Federation, however they took a

view of the draft Commonwealth constitution as undemocratic, believing

the Senate as proposed was much too powerful, similar to the

anti-reformist Colonial state upper houses, and the UK House of Lords.

When the draft was submitted to a referendum on 3 June 1898, Labour

opposed it, with Watson prominent in the campaign, and saw the

referendum rejected. Watson

was devoted to the idea of a referendum as an ideal feature of

democracy. To ensure that Reid might finally bring New South Wales into

national union on an amended draft constitution, Watson helped to

negotiate a deal, involving the party executive, that included the

nomination of four Labor men to the Legislative Council. At

the March 1899 annual party conference, Hughes and Holman moved to have

those arrangements nullified and party policy on Federation changed,

thus thwarting Reid's plans. Watson, for once, got angry; he 'jumped to

his feet in a most excited manner and in heated tones … contended …

that they should not interfere with the referendum'. The motion was

lost. The four party men were nominated to the council on 4 April and

the bill approving the second referendum, to be held on 20 June, was

passed on 20 April. Labour,

including Watson, opposed the final terms of the Commonwealth

Constitution, however their voting status was not enough to stop it

from proceeding, and unlike Holman and Hughes, he believed that it

should be submitted to the people. Nevertheless, with all but two of

the Labour parliamentarians, he campaigned against the 'Yes' vote at

the referendum. When the Constitution was accepted, he agreed that 'the

mandate of the majority will have to be obeyed'. He had made an

essential contribution to that democratic decision. Watson successfully ran for the new federal Parliament at the inaugural 1901 federal election, in the House of Representatives rural seat of Bland. Arriving in May in the temporary seat of government, Melbourne,

Watson was elected the first leader of the Federal Parliamentary Labour

Party (usually known as the Caucus) on 8 May 1901, the day before the

opening of the parliament. McGowen had failed to gain election, and the other prominent New South Wales MP elected, Hughes, had too many enemies. Watson, though a compromise choice, soon established his authority as leader. In

the federal Parliament, where Labour was the smallest of the three

parties, but held the balance of power, Watson pursued the same policy

as Labour had done in the colonial parliaments. He kept the Protectionist governments of Edmund Barton and Alfred Deakin in office, in exchange for legislation enacting the Labour platform. Watson,

as a Labour moderate, genuinely admired Deakin and shared his liberal

views on many subjects. Deakin reciprocated this sentiment. He wrote in

one of his anonymous articles in a London newspaper: "The Labour

section has much cause for gratitude to Mr Watson, the leader whose

tact and judgement have enabled it to achieve many of its Parliamentary

successes." Labour under Watson more than doubled their vote at the 1903 federal election and

continued to hold the balance of power. In April 1904, however, Watson

and Deakin fell out over the issue of extending the scope of industrial

relations laws concerning the Conciliation and Arbitration Bill to cover state public servants, the fallout causing Deakin to resign. Free Trade leader George Reid declined to take office, which saw Watson become the first Labour Prime Minister of Australia, and the world's first Labour head of government at a national level (Anderson Dawson had

lead a short-lived Labour state government in Queensland in December

1899). He was aged only 37, and is still the youngest Prime Minister in

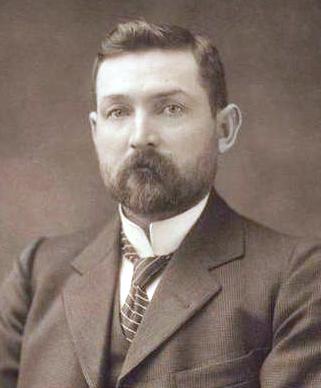

Australia's history. Billy Hughes later recalled the first meeting of the Labour Cabinet with characteristic sharp wit: Mr

Watson, the new Prime Minister entered the room, and seated himself at

the head of the table. All eyes were riveted on him; he was worth going

miles to see. He had dressed for the part; his Vandyke beard was

exquisitely groomed, his abundant brown hair smoothly brushed. His

morning coat and vest, set off by dark striped trousers, beautifully

creased and shyly revealing the kind of socks that young men dream

about; and shoes to match. He was the perfect picture of the statesman,

the leader. Despite

the apparent fitness of the new Prime Minister for his role, the

government hung on the fine thread of Deakin's promise of ‘fair play’.

The triumph of the historic first Australian Labor government was a

qualified one – Labour did not have the numbers to implement key

policies. The ‘three elevens’ – the lack of a definite majority in the

parliament after the second federal election – dogged Watson just as it

had Deakin. Six bills were enacted during Watson's brief government. All but one – an amended Acts Interpretation Act 1904 – were supply bills. The significant legislative concern of the Watson government was the advancement of the troublesome Conciliation and Arbitration Bill, which was defeated. Although Watson sought a dissolution of parliament so that an election could be held, the Governor-General Lord Northcote refused.

Unable to command a majority in the House of Representatives, Watson

resigned the premiership less than four months after taking office, his

term ending on 18 August 1904 (Deakin was later defeated on a similar

bill). Free Trade leader George Reid became Prime Minister. The Conciliation and Arbitration Act was assented to by the end of the year, and it extended to state public servants, as Watson had proposed. Watson led the Labour Party into the 1906 federal election and improved its position again. At this election the seat of Bland was abolished, so he shifted to the seat of South Sydney. But in October 1907, mainly due to concern over the health of his wife Ada, he resigned the Labour leadership in favour of Andrew Fisher. He retired from politics, aged only 42, prior to the 1910 federal election, at which Fisher beat Deakin comfortably. Out of the Parliamentary arena, Watson continued to work for Labor, becoming Director of Labor Papers Ltd, publishers of The Worker, the Australian Workers Union paper.

He also pursued a business career and was also a parliamentary

lobbyist. But in 1916 the Labor Party split over the issue of conscription for World War I,

and Watson sided with Hughes and the conscriptionists. He was expelled

from the party he had helped found. He remained active in the affairs

of Hughes's Nationalist Party until 1922, but after that he drifted out of politics altogether. Watson devoted the rest of his life to business. He helped found the National Roads and Motorists Association (NRMA) and remained its chairman until his death. He was also a founder of the Australian Motorists Petrol Co Ltd (Ampol). His wife Ada died in 1921. On

30 October 1925 Watson married Antonia Mary Gladys Dowlan in the same

church in which he had married Ada 36 years previously. His second wife

was a 23-year-old waitress from Western Australia whom he had met when

she served his table at the Commercial Travellers’ Club he frequented

when in Sydney. He and Antonia had one daughter, Jacqueline. Watson died at his home in the Sydney suburb of Double Bay.

In April 2004 the Labor Party marked the centenary of the Watson Government with a series of public events in Canberra and Melbourne, attended by then party leader Mark Latham and former leaders Gough Whitlam, Bob Hawke and Paul Keating. Watson's daughter, Jacqueline Dunn, 77, was guest of honour at these functions. The Canberra suburb Watson and the federal electorate of Watson are named after him. In 1969 he was honoured on a postage stamp bearing his portrait issued by Australia Post.