<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Saunders Mac Lane, 1909

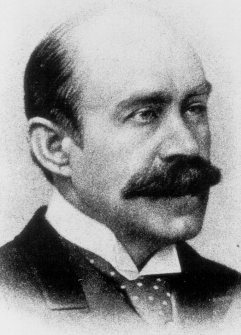

- Writer Walter Horatio Pater, 1839

- Diplomat Raoul Wallenberg, 1912

PAGE SPONSOR

Walter Horatio Pater (4 August 1839 – 30 July 1894) was an English essayist, critic of art and literature, and writer of fiction.

Born in Stepney in London's East End, Walter Pater was the second son of Richard Glode Pater, a physician who had moved to London in the early 19th century to practise medicine among the poor. Dr Pater died while Walter was an infant and the family moved to Enfield, London. Walter attended Enfield Grammar School and was individually tutored by the headmaster.

In 1853 he was sent to The King's School, Canterbury, where the beauty of the cathedral made an impression that would remain with him all his life. He was fourteen when his mother, Maria Pater, died in 1854. As a schoolboy Pater read John Ruskin's Modern Painters, which helped inspire his lifelong attraction to the study of art and gave him a taste for well crafted prose. He gained a school exhibition, with which he proceeded in 1858 to Queen’s College, Oxford.

As an undergraduate Pater was a "reading man", with literary and philosophical interests beyond the prescribed texts. Flaubert, Gautier, Baudelaire and Swinburne were

among his early favourites. Visiting his aunt and sisters in Germany

during the vacations he learned German and began to read Hegel and the German philosophers. The scholar Benjamin Jowett was

struck by his potential and offered to give him private lessons. In

Jowett's classes, however, Pater was a disappointment; he took a Second

in literae humaniores in 1862. As a boy Pater had cherished the idea of entering the Anglican Church,

but at Oxford his faith in Christianity had been shaken. In spite of

his inclination towards the ritual and aesthetic elements of the

church, he had little interest in Christian doctrine and did not pursue

ordination. After graduating, Pater remained in Oxford and taught

Classics and Philosophy to private students. His years of study and

reading now paid dividends: he was offered a classical fellowship in

1864 at Brasenose on the strength of his ability to teach modern German philosophy, and he settled down to a university career. The

opportunities for wider study and teaching at Oxford, combined with

formative visits to the Continent - in 1865 he visited Florence, Pisa

and Ravenna - meant that Pater's preoccupations now multiplied. He

became acutely interested in art and literature, and started to write

articles and criticism. First to be printed was an essay on the metaphysics of Coleridge, contributed in 1866 to the Westminster Review. A few months later his essay on Winckelmann (1867), an early expression of his idealism and his admiration for classicism, appeared in the same review, followed by 'The Poems of William Morris' (1868), a complementary piece on romanticism. In the following years the Fortnightly Review printed his essays on Leonardo da Vinci (1869), Sandro Botticelli (1870), and Michelangelo (1871). The last three, with other similar pieces, were collected in his Studies in the History of the Renaissance (1873), renamed in the second and later editions The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry. The Leonardo essay contains Pater's celebrated reverie on the Mona Lisa ("probably still the most famous piece of writing about any picture in the world"); the Botticelli essay was the first in English on this painter, contributing to the revival of interest in this artist. An essay on 'The School of Giorgione' (Fortnightly Review, 1877), added to the third edition (1888), contains Pater's much quoted maxim "All art constantly aspires towards the condition of music"

(i.e. the arts seek to unify subject matter and form, and music is the

only art in which subject and form are seemingly one). The final

paragraphs of the 1868 William Morris essay were included as the book's

'Conclusion'. This

brief 'Conclusion' was to be Pater's most influential – and

controversial – publication. It asserts that our physical lives are

made up of scientific processes and elemental forces in perpetual

motion, "renewed from moment to moment but parting sooner or later on

their ways". In the mind "the whirlpool is still more rapid": a drift

of perceptions, feelings, thoughts and memories, reduced to impressions

"unstable, flickering, inconstant", "ringed round for each one of us by

that thick wall of personality"; and "with the passage and dissolution

of impressions ... [there is a] continual vanishing away, that strange,

perpetual weaving and unweaving of ourselves". Since all is in flux, to

get the most from life we must learn to discriminate through "sharp and

eager observation": for "every moment some form grows perfect in hand

or face; some tone on the hills or the sea is choicer than the rest;

some mood of passion or insight or intellectual excitement is

irresistibly real and attractive for us, – for that moment only".

Through such discrimination we may "get as many pulsations as possible

into the given time": "To burn always with this hard, gem like flame,

to maintain this ecstasy, is success in life." Forming habits means

failure on our part, for habit connotes the stereotypical. "While all

melts under our feet," Pater wrote, "we may well catch at any exquisite

passion, or any contribution to knowledge that seems by a lifted

horizon to set the spirit free for a moment, or any stirring of the

senses, or work of the artist’s hands. Not to discriminate every moment

some passionate attitude in those about us in the brilliancy of their

gifts is, on this short day of frost and sun, to sleep before evening."

The resulting "quickened, multiplied consciousness" counters our

insecurity in the face of the flux. Moments

of vision may come from simple natural effects, as Pater notes

elsewhere in the book: "A sudden light transfigures a trivial thing, a

weathervane, a windmill, a winnowing flail, the dust in the barn door;

a moment - and the thing has vanished, because it was pure effect; but

it leaves a relish behind it, a longing that the accident may happen

again." Or

they may come from "intellectual excitement", from philosophy, science

and the arts. Of these, a passion for the arts, "a desire of beauty",

has (in the summary of one of Pater's editors)

"the greatest potential for staving off the sense of transience,

because in the arts the perceptions of highly sensitive minds are

already ordered; we are confronted with a reality already refined and

we are able to reach the personality behind the work". The Renaissance,

which appeared to some to endorse "hedonism" and amorality, provoked

criticism from conservative quarters, including disapproval from

Pater's former tutor at Queen's, from the college chaplain at Brasenose

and from the Bishop of Oxford. In 1874 Pater was turned down at the last moment by his erstwhile mentor Benjamin Jowett, Master of Balliol, for a previously promised proctorship. Letters have recently emerged documenting a "romance" with a nineteen year old Balliol undergraduate, William Money Hardinge,

who had attracted unfavorable attention as a result of his outspoken

homosexuality and blasphemous verse, and who later became a novelist. Many of Pater's works focus on male beauty, friendship and love, either in a Platonic way or, obliquely, in a more physical way. In 1876 W.H. Mallock parodied Pater's message in a satirical novel The New Republic, depicting Pater as a typically effete English aesthete. This appeared during the competition for the Oxford Professorship of Poetry and played a role in convincing Pater to remove himself from consideration.

A few months later Pater published what may have been a subtle riposte:

'A Study of Dionysus' the outsider god, persecuted for his new religion of ecstasy, who vanquishes the forces of reaction (The Fortnightly Review, Dec. 1876). Now at the centre of a small but gifted circle in Oxford (he tutored Gerard Manley Hopkins), Pater was gaining respect in the London literary world and beyond, numbering some of the Pre-Raphaelites among his friends. Conscious of his growing influence and aware that the 'Conclusion' to his Renaissance could

be misconstrued as amoral, he withdrew the essay from the second

edition in 1877 (he was to reinstate it with minor modifications in the

third in 1888) and now set about clarifying and exemplifying his ideas

through fiction. To this end he published in 1878 in Macmillan's Magazine an evocative semi-autobiographical sketch entitled The Child in the House about

some of the formative experiences of his childhood. This was to be the

first of a dozen or so "Imaginary Portraits", a genre Pater could be

said to have invented and in which he came to specialise. These are not

so much stories – their narrative interest is limited – as

psychological studies of fictional characters in historical settings,

often personifications of new concepts at turning points in the history

of ideas or emotion. Some look forward, dealing with innovation in the

visual arts and philosophy; others look back, dramatizing neo-pagan

themes. Many are veiled self portraits exploring dark personal

preoccupations. Planning

a major work, Pater now resigned his teaching duties in 1882, though he

retained his Fellowship and the college rooms he had occupied since

1864, and made a research visit to Rome. In his philosophical novel Marius the Epicurean (1885), an extended imaginary portrait set in the Rome of the Antonines,

which Pater believed had parallels with his own century, he examines

the "sensations and ideas" of a young Roman of integrity, who pursues

an ideal of the "aesthetic" life - a life based on αίσθησις, perception

- tempered by asceticism.

Leaving behind the religion of his childhood, sampling one philosophy

after another but settling on none, disillusioned by Rome itself,

becoming secretary to the Stoic emperor Marcus Aurelius, Marius tests during the course of a heuristic journey his author's theory of the stimulating effect of the pursuit of sensations and ideas as an ideal in itself, finally facing the facts of isolation and solipsism.

The novel's opening and closing episodes betray Pater's continuing

nostalgia for the atmosphere, ritual and community of the religious

faith he had lost. Marius was

favourably reviewed and sold well; a second impression came out in the

same year. For the second edition (1892) Pater made extensive stylistic

revisions. In 1885, on the resignation of John Ruskin, Pater became a candidate for the Slade Professorship of Fine Art at Oxford University,

but though in many ways the strongest of the field, he withdrew from

the competition, discouraged by continuing hostility in official

quarters. In the wake of this disappointment but buoyed by the success of Marius,

he moved with his sisters from north Oxford (2 Bradmore Road), their

home since 1869, to London (12 Earl's Terrace, Kensington), where he

was to remain till 1893 and where he was to enjoy his status of minor

literary celebrity. From 1885 to 1887 Pater published four new imaginary portraits in Macmillan's Magazine, each set at a turning point in the history of ideas or art - 'A Prince of Court Painters' (1885) (on Watteau and Jean-Baptiste Pater), 'Sebastian van Storck' (1886) (17th century Dutch society and painting, and the philosophy of Spinoza),

'Denys L'Auxerrois' (1886) (the medieval cathedral builders), and 'Duke

Carl of Rosenmold' (1887) (the German Renaissance). These were

collected in the volume Imaginary Portraits (1887).

Here Pater's examination of the tensions between tradition and

innovation, intellect and sensation, asceticism and aestheticism, social mores and

amorality, becomes increasingly complex. Implied warnings against the

pursuit of extremes in matters intellectual, aesthetic or sensual are

unmistakable. The second portrait, 'Sebastian van Storck', a powerful

critique of philosophical solipsism, is perhaps Pater's most striking

work of fiction. In 1889 Pater published Appreciations, with an Essay on Style,

a collection of previously printed essays on literature. It was well

received. The volume includes an appraisal of the poems of Dante Gabriel Rossetti,

first printed in 1883, a few months after Rossetti's death. Pater

suppressed, however, in the second edition (1890) the essay on

'Aesthetic Poetry' - a revised version of his 1868 William Morris piece

- evidence of his growing cautiousness in response to establishment

criticism. In

1893 Pater and his sisters returned to Oxford (64 St Giles). He was now

much in demand as a lecturer. In this year appeared his book Plato and Platonism.

Here and in other essays on ancient Greece Pater relates to Greek

culture the romanticism - classicism dialectic which he had first

explored in his essay 'Romanticism' (1876), reprinted as the

'Postscript' to Appreciations.

"All through Greek history," he writes, "we may trace, in every sphere

of activity of the Greek mind, the action of these two opposing

tendencies, the centrifugal and centripetal. The centrifugal - the

Ionian, the Asiatic tendency - flying from the centre, throwing itself

forth in endless play of imagination, delighting in brightness and

colour, in beautiful material, in changeful form everywhere, its

restless versatility driving it towards the development of the

individual": and "the centripetal tendency", drawing towards the

centre, "maintaining the Dorian influence of a severe simplification

everywhere, in society, in culture". Harold Bloom noted

that "Pater praises Plato for Classic correctness, for a conservative

centripetal impulse, against his [Pater's] own Heraclitean

Romanticism," but "we do not believe him when he presents himself as a

centripetal man". The

volume, which also includes a sympathetic study of ancient Sparta

('Lacedaemon', first printed in 1892), was praised by Jowett. "The change that occurs between Marius and Plato and Platonism," writes Anthony Ward, "is one from a sense of defeat in scepticism to a sense of triumph in it." On 30 July 1894 Pater died suddenly in his Oxford home of heart failure brought on by rheumatic fever, at the age of 54. He was buried at Holywell Cemetery, Oxford. In 1895 a friend and former student of Pater's, Charles Lancelot Shadwell, a Fellow of Oriel, collected and published as Greek Studies Pater's essays on Greek mythology, religion, art and literature. This volume contains a reverie on the boyhood of Hippolytus, 'Hippolytus Veiled' (first published in Macmillan's Magazine in 1889), which has been called "the finest prose ever inspired by Euripides". The sketch illustrates a paradox central to Pater's sensibility and writings: a leaning towards ascetic beauty apprehended sensuously. In the same year Shadwell also assembled other uncollected pieces and published them as Miscellaneous Studies.

This volume contains 'The Child in the House' and another two obliquely

self revelatory Imaginary Portraits, 'Emerald Uthwart' (first published

in The New Review in 1892) and 'Apollo in Picardy' (from Harper's Magazine,

1893), and two essays that point to a revival in Pater's final years of

his earlier interest in Gothic cathedrals, sparked by regular visits to

northern Europe with his sisters. Charles Shadwell "in his younger days" had been "strikingly handsome, both in figure and feature", "with a face like those to be seen on the finer Attic coins"; he had been the unnamed inspiration of

an unpublished early paper of Pater's, 'Diaphaneitè' (1864), a

tribute to youthful beauty and intellect, the manuscript of which Pater

gave to Shadwell. This piece Shadwell also included in Miscellaneous Studies. Shadwell had accompanied Pater on his 1865 visit to Italy, and Pater was to dedicate The Renaissance to him and to write a preface to Shadwell's edition of The Purgatory of Dante Alighieri (1892). In 1896 Shadwell edited and published Pater's unfinished novel, Gaston de Latour,

set in 16th century France, the product of the author's growing

interest in his later years in French history, philosophy, literature,

and architecture. Essays from The Guardian and Uncollected Essays (later titled Sketches and Reviews)

were privately printed in 1896 and 1903 respectively. A Collected

Edition of Pater's works, including all but the last volume, was issued

in 1901 and was reprinted frequently until the late 1920s.

Toward

the end of his life Pater's writings were exercising a considerable

influence. The principles of what would be known as the Aesthetic Movement were partly traceable to him, and his effect was particularly felt on one of the movement's leading proponents, Oscar Wilde, who paid tribute to him in The Critic as Artist (1891). Among art critics influenced by Pater were Bernard Berenson, Roger Fry, Kenneth Clark and Richard Wollheim. In literature some of the early Modernists such as Marcel Proust, James Joyce, W.B. Yeats, Ezra Pound and Wallace Stevens admired his writing"; and

Pater's influence can be traced in the subjective,

stream-of-consciousness novels of the early 20th century. In literary

criticism, Pater's emphasis on subjectivity and on the autonomy of the

reader helped prepare the way for the revolutionary approaches to

literary studies of the modern era. Among ordinary readers, idealists

have found, and always will find inspiration in his desire "to burn

always with this hard, gemlike flame", in his pursuit of the "highest

quality" in "moments as they pass". Pater's critical method was outlined in the 'Preface' to The Renaissance (1873)

and refined in his later writings. In the 'Preface' he argues initially

for a subjective, relativist response to life, ideas, art, as opposed

to the drier, more objective, somewhat moralistic criticism practised by Matthew Arnold and

others. "The first step towards seeing one's object as it really is,"

Pater wrote, "is to know one's own impression, to discriminate it, to

realise it distinctly. What is this song or picture, this engaging

personality in life or in a book, to me?"

When we have formed our impressions we proceed to find "the power or

forces" which produced them, the work's "virtue". "Pater moves, in

other words, from effects to causes, which are his real interest," noted Richard Wollheim. Among

these causes are, pre-eminently, original temperaments and types of

mind; but Pater "did not confine himself to pairing off a work of art

with a particular temperament. Having a particular temperament under

review, he would ask what was the range of

forms in which it might find expression. Some of the forms will be

metaphysical doctrines, ethical systems, literary theories, religions,

myths. Pater's scepticism led him to think that in themselves all such

systems lack sense or meaning - until meaning is conferred upon them by

their capacity to give expression to a particular temperament." Pater's

critical method, then, sometimes seen as a quest for "impressions", is

really more a quest for the sources of individual expression. Pater

was much admired for his prose style, which he strove to make worthy of

his own aesthetic ideals, taking great pains and fastidiously

correcting his work. He kept on his desk little squares of paper, each

with its ideas, and shuffled them about attempting to form a sequence

and pattern. "I

have known writers of every degree, but never one to whom the act of

composition was such a travail and an agony as it was to Pater," wrote Edmund Gosse,

who also described Pater's method of composition: "So conscious was he

of the modifications and additions which would supervene that he always

wrote on ruled paper, leaving each alternate line blank." "Unlike those who were caught by Flaubert's theory of the unique word and the only epithet," wrote Osbert Burdett, "Pater

sought the sentence, and the sentence in relation to the paragraph, and

the paragraph as a movement in the chapter. The numerous parentheses

deliberately exchanged a quick flow of rhythm for pauses, for charming

little eddies by the way." As a result, Pater's style, serene and

contemplative in tone, suggests, in the words of G.K. Chesterton, a "vast attempt at impartiality." Indeed, in its richness, depth, and acuity, in its sensuous rhythms, his style was perfectly attuned to his philosophy of life.