<Back to Index>

- Physicist Jean Cabannes, 1885

- Composer Giovanni Legrenzi, 1626

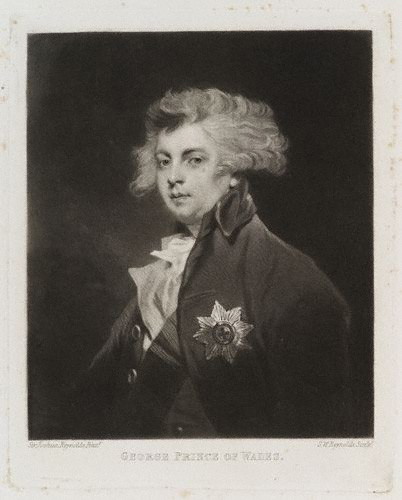

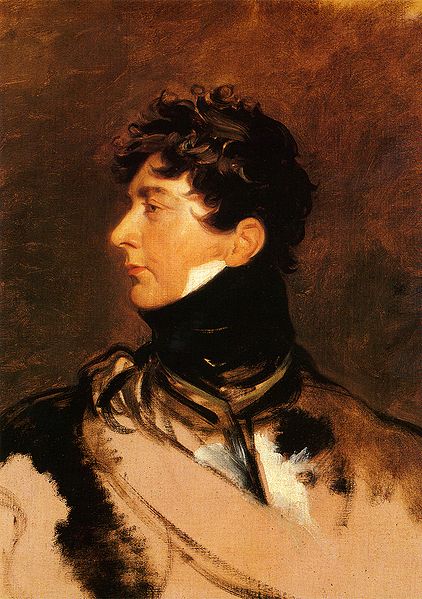

- King of the United Kingdom George IV, 1762

PAGE SPONSOR

George IV (George Augustus Frederick; 12 August 1762 – 26 June 1830) was the King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and also of Hanover from the death of his father, George III, on 29 January 1820 until his own death ten years later. From 1811 until his accession, he served as Prince Regent during his father's relapse into mental illness.

George IV led an extravagant lifestyle that contributed to the fashions of the British Regency. He was a patron of new forms of leisure, style and taste. He commissioned John Nash to build the Royal Pavilion in Brighton and remodel Buckingham Palace, and Sir Jeffry Wyatville to rebuild Windsor Castle. He was instrumental in the foundation of the National Gallery, London, and King's College, London. He had a poor relationship with both his father and his wife, Caroline of Brunswick, whom he even forbade to attend his coronation. He introduced the unpopular Pains and Penalties Bill in a desperate, unsuccessful, attempt to divorce his wife. For most of George's regency and reign, Lord Liverpool controlled the government as Prime Minister. George's governments, with little help from the King, presided over victory in the Napoleonic Wars, negotiated the peace settlement, and attempted to deal with the social and economic malaise that followed. He had to accept George Canning as foreign minister and later prime minister, and drop his opposition to Catholic Emancipation. His

charm and culture earned him the title "the first gentleman of

England", but his bad relations with his father and wife, and his

dissolute way of life earned him the contempt of the people and dimmed

the prestige of the monarchy. Taxpayers were angry at his wasteful

spending in time of war. He did not provide national leadership in time

of crisis, nor a role model for his people. His ministers found his

behavior selfish, unreliable, and irresponsible. At all times he was

much under the influence of favourites. George was born at St James's Palace, London, on 12 August 1762. As the eldest son of a British sovereign, he automatically became Duke of Cornwall and Duke of Rothesay at birth; he was created Prince of Wales and Earl of Chester a few days afterwards. On 18 September of the same year, he was baptised by Thomas Secker, Archbishop of Canterbury. His godparents were the Duke of Mecklenburg - Strelitz (his maternal uncle, for whom the Duke of Devonshire, Lord Chamberlain, stood proxy), the Duke of Cumberland (his twice - paternal great - uncle), and the Dowager Princess of Wales (his paternal grandmother). George was a talented student, quickly learning to speak French, German and Italian in addition to his native English. At

the age of 18 he was given a separate establishment, and in dramatic

contrast with his prosaic, scandal - free father threw himself with

zest

into a life of dissipation and wild extravagance involving heavy

drinking and numerous mistresses and escapades. He was a witty

conversationalist, drunk or sober, and showed good, but expensive,

taste in decorating his palace. The

Prince turned 21 in 1783, and obtained a grant of £60,000 (equal

to £5,744,000 today) from Parliament and an annual income of

£50,000 (equal to £4,786,000 today) from his father. It was

far too little for his needs. (The stables alone cost £31,000 a

year.) He then established his residence in Carlton House, where he lived a profligate life. Animosity developed between the Prince and his father, who desired more frugal behaviour on the part of the heir - apparent. The King, a political conservative, was also alienated by the Prince's adherence to Charles James Fox and other radically - inclined politicians. Soon after he reached the age of 21, the Prince became infatuated with Maria Fitzherbert. She was a commoner, six years his elder, twice widowed, and a Roman Catholic. Despite her complete unsuitability, the Prince was determined to marry her. This was in spite of the Act of Settlement 1701, which barred the spouse of a Catholic from succeeding to the throne, and the Royal Marriages Act 1772, which prohibited his marriage without the consent of the King, which would never have been granted. Nevertheless, the couple contracted a marriage on 15 December 1785 at her house in Park Street, Mayfair. Legally the union was void, as the King's consent was not granted (and never even requested). However, Mrs. Fitzherbert believed that she was the Prince's canonical and

true wife, holding the law of the Church to be superior to the law of

the State. For political reasons, the union remained secret and Mrs.

Fitzherbert promised not to reveal it. The

Prince was plunged into debt by his exorbitant lifestyle. His father

refused to assist him, forcing him to quit Carlton House and live at

Mrs. Fitzherbert's residence. In 1787, the Prince's political allies

proposed to relieve his debts with a parliamentary grant. The Prince's

relationship with Mrs. Fitzherbert was suspected, and revelation of the

illegal marriage would have scandalized the nation and doomed any

parliamentary proposal to aid him. Acting on the Prince's authority, the Whig leader Charles James Fox declared that the story was a calumny. Mrs.

Fitzherbert was not pleased with the public denial of the marriage in

such vehement terms and contemplated severing her ties to the Prince.

He appeased her by asking another Whig, Richard Brinsley Sheridan,

to restate Fox's forceful declaration in more careful words.

Parliament, meanwhile, granted the Prince £161,000 (equal to

£16,775,000 today) to pay his debts and £60,000 (equal to

£6,252,000 today) for improvements to Carlton House. It is now conjectured that King George III suffered from the hereditary disease porphyria. In

the summer of 1788 his mental health deteriorated, but he was

nonetheless able to discharge some of his duties and to declare

Parliament prorogued from

25 September to 20 November. During the prorogation George III became

deranged, posing a threat to his own life, and when Parliament

reconvened in November the King could not deliver the customary Speech from the Throne during the State Opening of Parliament.

Parliament found itself in an untenable position; according to

long established law it could not proceed to any business until the

delivery of the King's Speech at a State Opening. Although

arguably barred from doing so, Parliament began debating a Regency. In

the House of Commons, Charles James Fox declared his opinion that the

Prince of Wales was automatically entitled to exercise sovereignty

during the King's incapacity. A contrasting opinion was held by the

Prime Minister, William Pitt the Younger, who argued that, in the absence of a statute to the contrary, the right to choose a Regent belonged to Parliament alone. He

even stated that, without parliamentary authority "the Prince of Wales

had no more right... to assume the government, than any other individual

subject of the country." Though

disagreeing on the principle underlying a Regency, Pitt agreed with Fox

that the Prince of Wales would be the most convenient choice for a

Regent. The

Prince of Wales — though offended by Pitt's boldness — did not lend his

full support to Fox's approach. The prince's brother, Prince Frederick, Duke of York, declared that the prince would not attempt to exercise any power without previously obtaining the consent of Parliament. Following

the passage of preliminary resolutions Pitt outlined a formal plan for

the Regency, suggesting that the powers of the Prince of Wales be

greatly limited. Among other things, the Prince of Wales would not be

able either to sell the King's property or to grant a peerage to

anyone other than a child of the King. The Prince of Wales denounced

Pitt's scheme, declaring it a "project for producing weakness,

disorder, and insecurity in every branch of the administration of

affairs." In the interests of the nation, both factions agreed to compromise. A

significant technical impediment to any Regency Bill involved the lack

of a Speech from the Throne, which was necessary before Parliament

could proceed to any debates or votes. The Speech was normally

delivered by the King, but could also be delivered by royal

representatives known as Lords Commissioners; but no document could empower the Lords Commissioners to act unless the Great Seal of the Realm was

affixed to it. The Seal could not be legally affixed without the prior

authorisation of the Sovereign. Pitt and his fellow ministers ignored

the last requirement and instructed the Lord Chancellor to

affix the Great Seal without the King's consent, as the act of affixing

the Great Seal in itself gave legal force to the Bill. This legal fiction was denounced by Edmund Burke as a "glaring falsehood", as a "palpable absurdity", and even as a "forgery, fraud". The Prince of Wales's brother, the Duke of York, described the plan as "unconstitutional and illegal." Nevertheless,

others in Parliament felt that such a scheme was necessary to preserve

an effective government. Consequently on 3 February 1789, more than two

months after it had convened, Parliament was formally opened by an

"illegal" group of Lords Commissioners. The Regency Bill was

introduced, but before it could be passed the King recovered. The King

declared retroactively that the instrument authorising the Lords

Commissioners to act was valid. The Prince of Wales's debts continued to climb, and his father refused to aid him unless he married his cousin, Caroline of Brunswick. In 1795, the Prince of Wales acquiesced, and they were married on 8 April 1795 at the Chapel Royal, St James's Palace.

The marriage, however, was disastrous; each party was unsuited to the

other. The two were formally separated after the birth of their only

child, Princess Charlotte, in 1796, and remained separated for the rest of their lives. The Prince of Wales remained attached to Mrs. Fitzherbert for the rest of his life, despite several periods of estrangement. Before meeting Mrs. Fitzherbert the Prince of Wales may have fathered several illegitimate children. His mistresses included Mary Robinson, an actress who was bought off with a generous pension when she threatened to sell his letters to the newspapers; Grace Elliott, the divorced wife of a physician; and Frances Villiers, Countess of Jersey, who dominated his life for some years. In later life, his mistresses were Isabella Seymour - Conway, Marchioness of Hertford, and finally, for the last ten years of his life, Elizabeth Conyngham, Marchioness Conyngham. The

problem of the Prince of Wales's debts, which amounted to the

extraordinary sum of £630,000 (equal to £49,820,000 today)

in 1795, was

solved (at least temporarily) by Parliament. Being unwilling to make an

outright grant to relieve these debts, it provided him an additional

sum of £65,000 (equal to £5,140,000 today) per annum. In

1803, a further £60,000 (equal to £4,486,000 today) was

added, and the Prince of Wales's debts of 1795 were finally cleared in

1806, although the debts he had incurred since 1795 remained. In

1804 a dispute arose over the custody of Princess Charlotte, which led

to her being placed in the care of the King, George III. It also led to

a Parliamentary Commission of Enquiry into Princess Caroline's conduct

after the Prince of Wales accused her of having an illegitimate son.

The investigation cleared Caroline of the charge but still revealed her

behaviour to be extraordinarily indiscreet. In late 1810, George III was once again overcome by his malady following the death of his youngest daughter, Princess Amelia.

Parliament agreed to follow the precedent of 1788; without the King's

consent, the Lord Chancellor affixed the Great Seal of the Realm to letters patentnaming Lords Commissioners. The Lords Commissioners, in the name of the King, signified the granting of the Royal Assent to a bill that became the Regency Act of 1811.

Parliament restricted some of the powers of the Prince Regent (as the

Prince of Wales became known). The constraints expired one year after

the passage of the Act. As the Prince of Wales became Prince Regent on 5 February, one of the most important political conflicts facing the country concerned Catholic emancipation, the movement to relieve Roman Catholics of various political disabilities. The Tories, led by the Prime Minister, Spencer Perceval,

were opposed to Catholic emancipation, while the Whigs supported it. At

the beginning of the Regency, the Prince of Wales was expected to

support the Whig leader, William Wyndham Grenville, 1st Baron Grenville.

He did not, however, immediately put Lord Grenville and the Whigs in

office. Influenced by his mother, he claimed that a sudden dismissal of

the Tory government would exact too great a toll on the health of the

King (a steadfast supporter of the Tories), thereby eliminating any

chance of a recovery. In

1812, when it appeared highly unlikely that the King would recover, the

Prince of Wales again failed to appoint a new Whig administration.

Instead, he asked the Whigs to join the existing ministry under Spencer

Perceval. The Whigs, however, refused to co-operate because of

disagreements over Catholic emancipation. Grudgingly, the Prince of

Wales allowed Perceval to continue as Prime Minister. On 10 May 1812, Spencer Perceval was assassinated by John Bellingham.

The Prince Regent was prepared to reappoint all the members of the

Perceval ministry under a new leader. The House of Commons formally

declared its desire for a "strong and efficient administration", so the Prince Regent then offered leadership of the government to Richard Wellesley, 1st Marquess Wellesley, and afterwards to Francis Rawdon - Hastings, 2nd Earl of Moira.

He doomed the attempts of both to failure, however, by forcing each to

construct a bipartisan ministry at a time when neither party wished to

share power with the other. Possibly using the failure of the two peers

as a pretext, the Prince Regent immediately reappointed the Perceval

administration, with Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool, as Prime Minister. The Tories, unlike Whigs such as Earl Grey,

sought to continue the vigorous prosecution of the war in Continental

Europe against the powerful and aggressive Emperor of the French, Napoleon I. An anti - French alliance, which included Russia, Prussia, Austria, Britain and several smaller countries, defeated Napoleon in 1814. In the subsequent Congress of Vienna, it was decided that the Electorate of Hanover, a state that had shared a monarch with Britain since 1714, would be raised to a Kingdom, known as the Kingdom of Hanover. Napoleon returned from exile in 1815, but was defeated at the Battle of Waterloo by Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, brother of Marquess Wellesley. That same year the British - American War of 1812 came to an end, with neither side victorious. During this period George took an active interest in matters of style and taste, and his associates such as the dandy Beau Brummell and the architect John Nash created the Regency style. In London Nash designed the Regency terraces of Regent's Park and Regent Street. George took up the new idea of the seaside spa and had the Brighton Pavilion developed as a fantastical seaside palace, adapted by Nash in the "Indian Gothic" style inspired loosely by the Taj Mahal, with extravagant "Indian" and "Chinese" interiors. When George III died in 1820, the Prince Regent ascended the throne as George IV, with no real change in his powers. By the time of his accession, he was obese and possibly addicted to laudanum. George IV's relationship with his wife Caroline had

deteriorated by the time of his accession. They had lived separately

since 1796, and both were having affairs. In 1814, Caroline left the

United Kingdom for continental Europe, but she chose to return for her

husband's coronation, and to publicly assert her rights as Queen

Consort. However, George IV refused to recognize Caroline as Queen, and

commanded British ambassadors to ensure that monarchs in foreign courts

did the same. By royal command, Caroline's name was omitted from the Book of Common Prayer, the liturgy of the Church of England.

The King sought a divorce, but his advisors suggested that any divorce

proceedings might involve the publication of details relating to the

King's own adulterous relationships. Therefore, he requested and

ensured the introduction of the Pains and Penalties Bill 1820,

under which Parliament could have imposed legal penalties without a

trial in a court of law. The bill would have annulled the marriage and

stripped Caroline of the title of Queen. The bill proved extremely

unpopular with the public, and was withdrawn from Parliament. George IV

decided, nonetheless, to exclude his wife from his coronation at Westminster Abbey,

on 19 July 1821. Caroline fell ill that day and died on 7 August;

during her final illness she often stated that she thought she had been

poisoned.

George's coronation was a magnificent and expensive affair, costing about £243,000 (£18,994,000 as of 2011), (for

comparison, his father's coronation had only cost about £10,000,

equal to £1,457,000 today). Despite the enormous cost, it was a

popular event. In 1821 the King became the first monarch to pay a state visit to Ireland since Richard II of England. The following year he visited Edinburgh for "one and twenty daft days." His visit to Scotland, organised by Sir Walter Scott, was the first by a reigning British monarch since the mid 17th century. George IV spent most of his later reign in seclusion at Windsor Castle, but he continued to intervene in politics. At first it was believed that he would support Catholic Emancipation,

as he had proposed a Catholic Emancipation Bill for Ireland in 1797,

but his anti - Catholic views became clear in 1813 when he privately

canvassed against the ultimately defeated Catholic Relief Bill of 1813.

By 1824 he was denouncing Catholic emancipation in public. Having

taken the coronation oath on his accession, George now argued that he

had sworn to uphold the Protestant faith, and could not support any

pro-Catholic measures. The influence of the Crown was so great, and the will of the Tories under Prime Minister Lord Liverpool so

strong, that Catholic emancipation seemed hopeless. In 1827, however,

Lord Liverpool retired, to be replaced by the pro-emancipation Tory George Canning.

When Canning entered office, the King, hitherto content with privately

instructing his ministers on the Catholic Question, thought it fit to

make a public declaration to the effect that his sentiments on the

question were those of his revered father, George III. Canning's

views on the Catholic Question were not well received by the most

conservative Tories, including the Duke of Wellington. As a result the

ministry was forced to include Whigs. Canning died later in that year, leaving Frederick John Robinson, 1st Viscount Goderich to

lead the tenuous Tory - Whig coalition. Lord Goderich left office in

1828, to be succeeded by the Duke of Wellington, who had by that time

accepted that the denial of some measure of relief to Roman Catholics

was politically untenable. With

great difficulty Wellington obtained the King's consent to the

introduction of a Catholic Relief Bill on 29 January 1829. Under

pressure from his fanatically anti-Catholic brother, the Duke of Cumberland, the King withdrew his approval and in protest the Cabinet resigned en masse on 4 March. The next day the King, now under intense political pressure,

reluctantly agreed to the Bill and the ministry remained in power. Royal Assent was finally granted to the Catholic Relief Act on 13 April. George

IV's heavy drinking and indulgent lifestyle had taken its toll on his

health by the late 1820s. His taste for huge banquets and copious

amounts of alcohol caused him to become obese, making him the target of

ridicule on the rare occasions that he did appear in public. He suffered from gout, arteriosclerosis, dropsy and possible porphyria; he would spend whole days in bed and suffered spasms of breathlessness that would leave him half-asphyxiated. Some

accounts claim that he showed signs of mental instability towards the

end of his life, although less extreme than his father; for example, he

sometimes claimed that he had been at the Battle of Waterloo, which may have been a sign of dementia or just a joke to annoy the Duke of Wellington.

He died at about half-past three in the morning of 26 June 1830 at

Windsor Castle; he called out "Good God, what is this?" clasped his

page's hand and said "my boy, this is death." He was buried in St George's Chapel, Windsor on 15 July. His only legitimate child, Princess Charlotte Augusta of Wales, had died from post-partum complications in 1817, after delivering a still born son. The second son of George III, Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany, had died in 1827. He was therefore succeeded by another brother, the third son of George III, Prince William, Duke of Clarence, who reigned as William IV. His

last years were marked by increasing physical and mental decay and

withdrawal from public affairs. Privately a senior aide to the king confided to his diary: "A

more contemptible, cowardly, selfish, unfeeling dog does not

exist.... There have been good and wise kings but not many of them... and

this I believe to be one of the worst." On George's death The Times captured

elite opinion succinctly: "There never was an individual less regretted

by his fellow creatures than this deceased king. What eye has wept for

him? What heart has heaved one throb of unmercenary sorrow? ... If

he ever had a friend — a devoted friend in any rank of life — we

protest that the name of him or her never reached us." During

the political crisis caused by Catholic emancipation, the Duke of

Wellington said that George was "the worst man he ever fell in with his

whole life, the most selfish, the most false, the most ill-natured, the

most entirely without one redeeming quality", but his eulogy delivered in the House of Lords called George "the most accomplished man of his age" and praised his knowledge and talent. Wellington's true feelings probably lie somewhere between these two extremes; as he

said later, George was "a magnificent patron of the arts ... the

most extraordinary compound of talent, wit, buffoonery, obstinacy, and

good feeling — in short a medley of the most opposite qualities, with a

great preponderence of good — that I ever saw in any character in my

life." George IV was described as the "First Gentleman of England" on account of his style and manners. Certainly,

he possessed many good qualities; he was bright, clever, and

knowledgeable. However, his laziness and gluttony led him to squander

much of his talent. As The Times once wrote, he would always prefer "a girl and a bottle to politics and a sermon." There

are many statues of George IV, a large number of which were erected

during his reign. In the United Kingdom, they include a bronze statue of him on horseback by Sir Francis Chantrey in Trafalgar Square and another outside the Royal Pavilion in Brighton. In Edinburgh, "George IV Bridge" is a main street linking the Old Town High Street to

the north over the ravine of the Cowgate, designed by the architect Thomas Hamilton in 1829 and completed in 1835. King's Cross, now a major transport hub sitting on the border of Camden and Islington in north London, takes its name from a short lived monument erected to George IV in the early 1830s. The

Regency period saw a shift in fashion that was largely determined by

George. After political opponents put a tax on wig powder, he abandoned

wearing a powdered wig in favour of natural hair. He

wore darker colours than had been previously fashionable as they helped

to disguise his size, favoured pantaloons and trousers over knee

breeches because they were looser, and popularised a high collar with

neck cloth because it hid his double chin. By 1797 his weight had reached 17 stone 7 pounds (111 kg or 245 lb), and by 1824 his corset was made for a waist of 50 inches (127 cm). His visit to Scotland in 1822 led to the revival, if not the creation, of Scottish tartandress as it is known today.