<Back to Index>

- Archaeologist Glenn Albert Black, 1900

- Poet Nur ad-Din Abd ar-Rahman Jami, 1414

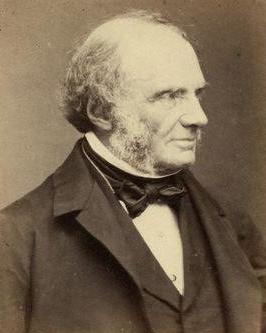

- Prime Minister of the United Kingdom John Russell, 1792

PAGE SPONSOR

John Russell, 1st Earl Russell, KG, GCMG, PC (18 August 1792 – 28 May 1878), known as Lord John Russell before 1861, was an English Whig and Liberal politician who served twice as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in the mid 19th century. He was the grandfather of Bertrand Russell, the mathematician, philosopher and political campaigner.

Russell was born into the highest echelons of the British aristocracy. The Russell family had been one of the principal Whig dynasties in England since the 17th century, and were among the richest handful of aristocratic landowning families in the country, but as a younger son of the 6th Duke of Bedford he was not in line to inherit the family estates. As a younger son, he bore the courtesy title "Lord John Russell", but as he was not a peer in his own right he was entitled to sit in the House of Commons.

He was educated at Westminster School and the University of Edinburgh, which he attended for three years but did not take a degree. Russell

entered parliament as a Whig in 1813. In 1819, Russell embraced the

cause of parliamentary reform, and led the more reformist wing of the

Whigs throughout the 1820s. When the Whigs came to power in 1830 in Earl Grey's government, Russell entered the government as Paymaster of the Forces, and was soon elevated to the Cabinet. He was one of the principal leaders of the fight for the Reform Act 1832, earning the nickname Finality Jack from his complacency pronouncing the Act a final measure. In 1834, when the leader of the Commons, Lord Althorp, succeeded to the peerage as Earl Spencer,

Russell became the leader of the Whigs in the Commons, a position he

maintained for the rest of the decade, until the Whigs fell from power

in 1841. In this position, Russell continued to lead the more reformist

wing of the Whig party, calling, in particular, for religious freedom,

and, as Home Secretary in the late 1830s, played a large role in

democratizing the government of British cities (other than London). In 1845, as leader of the Opposition, Russell came out in favour of repeal of the Corn Laws, forcing Conservative Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel to follow him. When the Conservatives split the next year over this issue, the Whigs returned to power and Russell became Prime Minister.

Russell's premiership was frustrating, and, due to party disunity and

his own ineffectual leadership, he was unable to get many of the

measures he was interested in passed. Russell's first government coincided with the Great Irish Famine of the late 1840s. Russell's government also saw conflict with his headstrong Foreign Secretary, Lord Palmerston,

whose belligerence and support for continental revolution he found

embarrassing. When, without royal approval, Palmerston recognized Napoleon III's

coup of 2 December 1851, Palmerston was forced to resign. Within a few

months Palmerston caused the defeat of Russell's ministry on the

militia bill (his "tit for tat with Johnny Russell"), and the ministry

soon collapsed. After a short lived minority Conservative government under the Earl of Derby, Russell brought the Whigs into a new coalition government with the Peelite Conservatives, headed by the Peelite Lord Aberdeen.

Russell served again as Leader of the House of Commons, and together

with Palmerston was instrumental in getting Britain involved in the Crimean War,

against the wishes of the cautious, Russophile Aberdeen. Incompetence

in the early stages of the war, however, led to the collapse of the

government, and Palmerston formed a new government. Although Russell

was initially included, he did not get on well with his former

subordinate, and temporarily retired from politics in 1855, focusing on

writing. In

1859, following another short lived Conservative government, Palmerston

and Russell made up their differences, and Russell consented to serve as Foreign Secretary in a new Palmerston cabinet - usually considered the first true Liberal Cabinet. This period was a particularly eventful one in the world outside Britain, seeing the Unification of Italy, the American Civil War, and the 1864 war over Schleswig - Holstein between

Denmark and the German states. Russell's handling of these crises was

not particularly noteworthy, and he was always overshadowed by his more

eminent chief. In particular, his attempts to attain British mediation

in the American war, which were shot down by the cautious Palmerston,

did not improve his position. Russell was elevated to the peerage as Viscount Amberley, of Amberley in the County of Gloucester and of Ardsalla in the County of Meath, and Earl Russell, of Kingston Russell in the County of Dorset, in 1861. As a peer in his own right, he sat in the House of Lords for the remainder of his career. When Palmerston suddenly died in late 1865, Russell again became Prime Minister.

His second premiership was short and frustrating, and Russell failed in

his great ambition of expanding the franchise - a task that would be

left to his Conservative successors, Derby and Benjamin Disraeli. In 1866, party disunity again brought down his government, and Russell went into permanent retirement. In 1876, his son, John Russell, Viscount Amberley, died, and he and his wife thereafter brought up his son Bertrand Russell, who afterwards became a renowned mathematician, philosopher and political campaigner, at their house in Pembroke Lodge, Richmond Park.

Their other children were The Hon. George Gilbert William Russell (14

April 1848 - 7 January 1933), who died unmarried and without issue, The

Hon. Francis Albert Rollo Russell (11 July 1849 - 30 March 1914), who

married twice and had issue by both his marriages, now extinct in male

line, Lady Georgiana Adelaide Russell (? - 25 September 1922), who

married and had issue, Lady Victoria Russell (20 October 1838 - 9 May

1880), who also married and had issue, and Lady Mary Augusta Russell

(1853 - 23 April 1933), who also died unmarried and without issue. He was succeeded as Liberal leader by former Peelite William Ewart Gladstone, and was thus the last true Whig to serve as Prime Minister. He may have served as Anthony Trollope's model for the character of Plantagenet Palliser.

An ideal statesman, said Trollope, should have "unblemished,

unextinguishable, inexhaustible love of country... But he should also be

scrupulous, and, as being scrupulous, weak." The 1832 Reform Act and the democratisation of the government of British cities are partly attributed to his efforts. He also worked for emancipation, leading the attack on the Test and Corporation acts, which were repealed in 1828, as well as towards legislation limiting working hours in factories in the 1847 Factory Act, and the Public Health Act of 1848. His

government's approach to dealing with the Irish Potato Famine is now

widely condemned as counterproductive, ill-informed and disastrous;

however, it has been argued that Russell himself (a "Foxite"

populist) was sympathetic to the plight of the Irish poor, and that

many of his relief proposals were blocked by his cabinet and the

British Parliament. In

1819 Lord John Russell published his book "Life of Lord Russell" about

his famous ancestor. Between 1853 and 1856, he edited the Memoirs,

Journal and Correspondence of Thomas Moore, which was published by

Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans over 8 volumes. A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens was dedicated to Lord John Russell "In remembrance of many public services and private kindnesses."