<Back to Index>

- Physicist Leopold Infeld, 1898

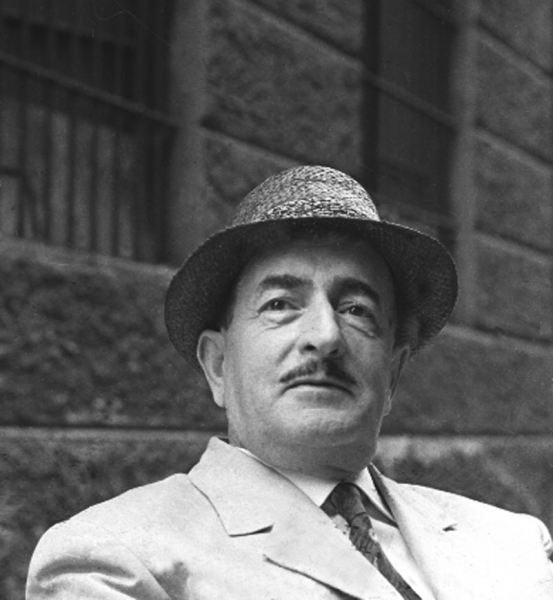

- Poet Salvatore Quasimodo, 1901

- 23rd President of the United States Benjamin Harrison, 1833

PAGE SPONSOR

Salvatore Quasimodo (August 20, 1901 – June 14, 1968) was an Italian author. In 1959, he won the Nobel Prize for Literature "for his lyrical poetry, which with classical fire expresses the tragic experience of life in our own times." Along with Giuseppe Ungaretti and Eugenio Montale, he is one of the foremost Italian poets of the 20th century.

Quasimodo was born in Modica, Sicily. In 1908 his family moved to Messina, as his father had been sent there to help the population struck by a devastating earthquake. The impressions of the effects of natural forces would have a great impact on the young Quasimodo. In 1919 he graduated from the local Technical College. In Messina he also made friends with Giorgio La Pira, future mayor of Florence.

In 1917 Quasimodo founded the short lived Nuovo giornale letterario ("New Literary Journal"), in which he published his first poems. In 1919 he moved to Rome to finish his engineering studies, but poor economic conditions forced him to find a work as a technical draughtsman. In the meantime he collaborated with several reviews and studied Greek and Latin.

In 1929, invited by Elio Vittorini, who had married Quasimodo's sister, he moved to Florence. Here he met poets such as Alessandro Bonsanti and Eugenio Montale. In 1930 he took a job with Italy's Civil Engineering Corps in Reggio Calabria. Here he met the Misefari brothers, who encouraged him to continue writing. Developing his nearness to the hermetism movement, Quasimodo published his first collection, Acque e terre ("Waters and Earths") in that year.

In 1931 he was transferred to Imperia and then to Genoa, where he got acquainted with Camillo Sbarbaro and other personalities of the Circoli magazine, with which Quasimodo started a prolific collaboration. In 1932 he published with them a new collection, Oboe sommerso, including all his lyrics from 1930 - 1932.

In 1934 Quasimodo moved to Milan. Starting from 1938 he devoted himself entirely to writing, working with Cesare Zavattini and for Letteratura, official review of the Hermetic movement. In 1938 he published Poesie, followed by the translations of Lirici Greci ("Greek Poets") in 1939.

Though an outspoken anti - Fascist, during World War II Quasimodo did not take part in the Italian resistance against the German occupation. In that period he devoted himself to the translation of the Gospel of John, of some of Catullus's cantos, and several episodes of the Odyssey. In 1945 he became a member of the Italian Communist Party.

In 1946 he published another collection, Giorno dopo giorno ("Day After Day"), which made clear the increasing moral engagement and the epic tone of social criticism of the author. The same theme characterized his next works, La vita non è sogno ("Life Is Not a Dream"), Il falso e il vero verde ("The False and True Green") and La terra impareggiabile ("The Incomparable Land"). In all this period Quasimodo did not stop producing translations of classic authors and collaborating as a journalist for some of the most prestigious Italian publications (mostly with articles about the theatre).

In the 1950s Quasimodo won the following awards: Premio San Babila (1950), Premio Etna - Taormina (1953), Premio Viareggio (1958) and, finally, the Nobel Prize for Literature (1959). In 1960 and 1967 he received honoris causa degrees from the Universities of Messina and Oxford, respectively.

In his last years the poet made numerous voyages to Europe and America, giving public speeches and public lectures of his poems, which had been translated in several foreign languages.

In June 1968, when he was in Amalfi for a discourse, Quasimodo was struck by a cerebral hemorrhage. He died a few days later in the hospital in Naples. He was interred in the Cimitero Monumentale in Milan. Traditional

literary critique divides Quasimodo's work into two major periods: the

hermetic period until World War II and the post - hermetic era until his

death. Although these periods are distinct, they are to be seen as a

single poetical quest. This quest or exploration for a unique language

took him through various stages and various modalities of expression. As an intelligent and clever poet, Quasimodo used a

hermetical, "closed" language to sketch recurring motifs like Sicily,

religion and death. Subsequently, the translation of authors from Roman

and Greek Antiquity enabled him to extend his linguistic toolkit. The

disgust and sense of absurdity of World War II also had its impact on

the poet's language. This bitterness, however, faded in his late

writings, and was replaced by the mature voice of an old poet

reflecting upon his world.