<Back to Index>

- Economist Kenneth Joseph Arrow, 1921

- Composer Moritz Moszkowski, 1854

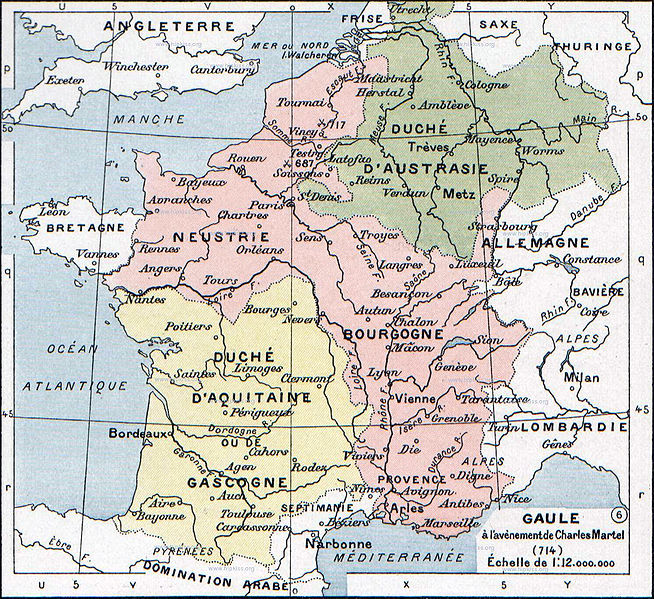

- Frankish Ruler Charles Martel, 688

PAGE SPONSOR

Charles Martel (Latin: Carolus Martellus) (c. 688 – 22 October 741), literally Charles the Hammer, was a Frankish military and political leader, who served as Mayor of the Palace under the Merovingian kings and ruled de facto during an interregnum (737 – 43) at the end of his life, using the title Duke and Prince of the Franks. In 739 he was offered the title of Consul by the Pope, but he refused. He is remembered for winning the Battle of Tours in 732, in which he defeated an invading Muslim army and halted northward Islamic expansion in western Europe.

A brilliant general, he lost only one battle in his career, (the Battle of Cologne). He is a founding figure of the Middle Ages, often credited with a seminal role in the development of feudalism and knighthood, and laying the groundwork for the Carolingian Empire. He was also the grandfather of Charlemagne.

Martel was born in Heristal (Herstal in present day Belgium), the illegitimate son of the mayor, duke Pepin II and his concubine Alpaida. In German speaking countries he is known as Karl Martell. Alpaida also bore Pepin another son, Childebrand. In December 714, Pepin of Heristal died. Prior to his death, he had, at his wife Plectrude's urging, designated Theudoald, his grandson by their son Grimoald, his heir in the entire realm. This was immediately opposed by the

nobles because Theudoald was a child of only eight years of age. To

prevent Charles using this unrest to his own advantage, Plectrude had

him imprisoned in Cologne, the city which was destined to be her capital. This prevented an uprising on his behalf in Austrasia, but not in Neustria. In 715, the Neustrian noblesse proclaimed Ragenfrid mayor of their palace on behalf of, and apparently with the support of, Dagobert III, the young king, who in theory had the legal authority to select a mayor, though by this time the Merovingian dynasty had lost most such powers. The

Austrasians were not to be left supporting woman and her young son for

long. Before the end of the year, Charles Martel had escaped from

prison and been acclaimed mayor by the nobles of that kingdom. The

Neustrians had been attacking Austrasia and the nobles were waiting for

a strong man to lead them against their invading countrymen. That year,

Dagobert died and the Neustrians proclaimed Chilperic II king without the support of the rest of the Frankish people. In 717, Chilperic and Ragenfrid together led an army into Austrasia. The Neustrians allied with another invading force under Radbod, King of the Frisians, and

met Charles in battle near Cologne, which was still held by Plectrude.

Charles had little time to gather men, or prepare, and the result was

the only defeat of his life. According to Strauss and Gustave, Martel

fought a brilliant battle, but realized he could not prevail because he

was outnumbered so badly, and retreated. In fact, he fled the field as

soon as he realized he did not have the time or the men to prevail,

retreating to the mountains of the Eifel to

gather men, and train them. The king and his mayor then turned to

besiege their other rival in the city and took it and the treasury, and

received the recognition of both Chilperic as king and Ragenfrid as

mayor. Plectrude surrendered on Theudoald's behalf. At

this juncture, however, events turned in favor of Charles. Having made

the proper preparations, he fell upon the triumphant army near Malmedy as it was returning to its own province, and, in the ensuing Battle of Amblève,

routed it. The few troops who were not killed or captured fled. Several

things were notable about this battle, in which Charles set the pattern

for the remainder of his military career: first, he appeared where his enemies least expected him, while they were marching triumphantly home and far outnumbered him. He also attacked when least expected, at midday, when armies of that era traditionally were resting. Finally, he attacked them how they

least expected it, by feigning a retreat to draw his opponents into a

trap. The feigned retreat, next to unknown in Western Europe at that

time - it was a traditionally eastern tactic — required both

extraordinary discipline on the part of the troops and exact timing on

the part of their commander. Charles, in this battle, had begun

demonstrating the military genius that would mark his rule. The result

was an unbroken victory streak that lasted until his death. In Spring 717, Charles returned to Neustria with an army and confirmed his supremacy with a victory at the Battle of Vincy, near Cambrai. He chased the fleeing king and mayor to Paris,

before turning back to deal with Plectrude and Cologne. He took her

city and dispersed her adherents. However, he allowed both Plectrude

and the young Theudoald to live and treated them with kindness — unusual for those Dark Ages, when mercy to a former jailer, or a potential rival, was rare. On this success, he proclaimed Clotaire IV king of Austrasia in opposition to Chilperic and deposed the archbishop of Rheims, Rigobert, replacing him with Milo, a lifelong supporter.

After subjugating all Austrasia, he marched against Radbod and pushed him back into his territory, even forcing the concession of West Frisia (later Holland). He also sent the Saxons back over the Weser and

thus secured his borders — in the name of the new king Clotaire, of

course. In 718, Chilperic responded to Charles' new ascendancy by

making an alliance with Odo the Great (or Eudes, as he is sometimes known), the duke of Aquitaine, who had made himself independent during the civil war in 715, but was again defeated, at the Battle of Soissons, by Charles. The king fled with his ducal ally to the land south of the Loire and Ragenfrid fled to Angers.

Soon Clotaire IV died and Odo gave up on Chilperic and, in exchange for

recognising his dukedom, surrendered the king to Charles, who

recognised his kingship over all the Franks in return for legitimate

royal affirmation of his mayoralty, likewise over all the kingdoms

(718). The

ensuing years were full of strife. Between 718 and 723, Charles secured

his power through a series of victories: he won the loyalty of several

important bishops and abbots (by donating lands and money for the

foundation of abbeys such as Echternach), he subjugated Bavaria and Alemannia, and he defeated the pagan Saxons. Having

unified the Franks under his banner, Charles was determined to punish

the Saxons who had invaded Austrasia. Therefore, late in 718, he laid

waste their country to the banks of the Weser, the Lippe, and the Ruhr. He defeated them in the Teutoburg Forest. In 719, Charles seized West Frisia without any great resistance on the part of the Frisians,

who had been subjects of the Franks but had seized control upon the

death of Pippin. Although Charles did not trust the pagans, their ruler, Aldegisel, accepted Christianity, and Charles sent Willibrord, bishop of Utrecht, the famous "Apostle to the Frisians" to convert the people. Charles also did much to support Winfrid, later Saint Boniface, the "Apostle of the Germans." When Chilperic II died the following year (720), Charles appointed as his successor the son of Dagobert III, Theuderic IV,

who was still a minor, and who occupied the throne from 720 to 737.

Charles was now appointing the kings whom he supposedly served, rois fainéants who

were mere puppets in his hands; by the end of his reign they were so

useless that he didn't even bother appointing one. At this time,

Charles again marched against the Saxons. Then the Neustrians rebelled

under Ragenfrid, who had left the county of Anjou. They were easily

defeated (724), but Ragenfrid gave up his sons as hostages in turn for

keeping his county. This ended the civil wars of Charles' reign. The

next six years were devoted in their entirety to assuring Frankish

authority over the dependent Germanic tribes. Between 720 and 723,

Charles was fighting in Bavaria, where the Agilolfing dukes had gradually evolved into independent rulers, recently in alliance with Liutprand the Lombard. He forced the Alemanni to accompany him, and Duke Hugbert submitted

to Frankish suzerainty. In 725 and 728, he again entered Bavaria and

the ties of lordship seemed strong. From his first campaign, he brought

back the Agilolfing princess Swanachild, who apparently became his

concubine. In 730, he marched against Lantfrid,

duke of Alemannia, who had also become independent, and killed him in

battle. He forced the Alemanni capitulation to Frankish suzerainty and

did not appoint a successor to Lantfrid. Thus, southern Germany once

more became part of the Frankish kingdom, as had northern Germany

during the first years of the reign. But by 731, his own realm secure, Charles began to prepare exclusively for the coming storm from the south and west. In 721, the emir of Córdoba had built up a strong army from Morocco, Yemen, and Syria to conquer Aquitaine,

the large duchy in the southwest of Gaul, nominally under Frankish

sovereignty, but in practice almost independent in the hands of the Odo the Great, the Duke of Aquitaine, since the Merovingian kings had lost power. The invading Muslims

besieged the city of Toulouse, then Aquitaine's most important city,

and Odo (also called Eudes, or Eudo) immediately left to find help. He

returned three months later just before the city was about to surrender

and defeated the Muslim invaders on June 9, 721, at what is now known

as the Battle of Toulouse.

This critical defeat was essentially the result of a classic enveloping

movement by Odo's forces. (After Odo originally fled, the Muslims

became overconfident and, instead of maintaining strong outer defenses

around their siege camp and continuous scouting, they did neither.)

Thus, when Odo returned, he was able to launch a near complete surprise

attack on the besieging force, scattering it at the first attack, and

slaughtering units caught resting or that fled without weapons or

armour. Due

to the situation in Iberia, Martel believed he needed a virtually

fulltime army — one he could train intensely — as a core of veteran Franks

who would be augmented with the usual conscripts called up in time of

war. (During the Early Middle Ages,

troops were only available after the crops had been planted and before

harvesting time.) To train the kind of infantry that could withstand

the Muslim heavy cavalry, Charles needed them year round, and he needed

to pay them so their families could buy the food they would have

otherwise grown. To obtain money he seized church lands and property,

and used the funds to pay his soldiers. The same Charles who had

secured the support of the ecclesia by

donating land, seized some of it back between 724 and 732. Of course,

Church officials were enraged, and, for a time, it looked as though

Charles might even be excommunicated for his actions. But then came a

significant invasion. Historian Paul K. Davis said in 100 Decisive Battles "Having

defeated Eudes, he turned to the Rhine to strengthen his northeastern

borders - but in 725 was diverted south with the activity of the

Muslims in Acquitane." Martel then concentrated his attention to the

Umayyads, virtually for the remainder of his life. Indeed, 12 years later, when he had thrice rescued Gaul from Umayyad invasions, Antonio Santosuosso noted

when he destroyed an Umayyad army sent to reinforce the invasion forces

of the 735 campaigns, "Charles Martel again came to the rescue." It

has been noted that Charles Martel could have pursued the wars against

the Saxons — but he was determined to prepare for what he thought was a

greater danger. It

is also vital to note that the Muslims were not aware, at that time, of

the true strength of the Franks, or the fact that they were building a

real army instead of the typical barbarian hordes that had dominated

Europe after Rome's fall. The Arab Chronicles, the history of that age,

show that Arab awareness of the Franks as a growing military power came

only after the Battle of Tours when the Caliph expressed shock at his

army's catastrophic defeat. The Cordoban emirate had previously invaded Gaul and had been stopped in its northward sweep at the Battle of Toulouse,

in 721. The hero of that less celebrated event had been Odo the Great,

Duke of Aquitaine, who was not the progenitor of a race of kings and

patron of chroniclers. It has previously been explained how Odo

defeated the invading Muslims, but when they returned, things were far different. The arrival in the interim of a new emir of Cordoba, Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi, who brought with him a huge force of Arabs and Berber horsemen,

triggered a far greater invasion. Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi had been at

Toulouse, and the Arab Chronicles make clear he had strongly opposed

the Emir's decision not to secure outer defenses against a relief

force, which allowed Odo and his relief force to attack with impunity

before the Islamic cavalry could assemble or mount. Abdul Rahman Al

Ghafiqi had no intention of permitting such a disaster again. This time

the Umayyad horsemen were ready for battle, and the results were

horrific for the Aquitanians. Odo, hero of Toulouse, was badly defeated in the Muslim invasion of 732 at the battle prior to the Muslim sacking of Bordeaux, and when he gathered a second army, at the Battle of the River Garonne — Western

chroniclers state, "God alone knows the number of the slain" — and the

city of Bordeaux was sacked and looted. Odo fled to Charles, seeking

help. Charles agreed to come to Odo's rescue, provided Odo acknowledged

Charles and his house as his overlords, which Odo did formally at once.

Charles was pragmatic; while most commanders would never use their

enemies in battle, Odo and his remaining Aquitanian nobles formed the right flank of Charles's forces at Tours. The Battle of Tours earned Charles the cognomen "Martel" ('Hammer'), for the merciless way he hammered his enemies. Many historians, including Sir Edward Creasy, believe that had he failed at Tours, Islam would probably have overrun Gaul, and perhaps the remainder of Western Europe. Gibbon made

clear his belief that the Umayyad armies would have conquered from Rome

to the Rhine, and even England, having the English Channel for

protection, with ease, had Martel not prevailed. Creasy said "the great

victory won by Charles Martel ... gave a decisive check to the career

of Arab conquest in Western Europe, rescued Christendom from Islam,

[and] preserved the relics of ancient and the germs of modern

civilization." Gibbon's belief that the fate of Christianity hinged on

this battle is echoed by other historians including John B. Bury,

and was very popular for most of modern historiography. It fell

somewhat out of style in the 20th century, when historians such as Bernard Lewis contended

that Arabs had little intention of occupying northern France. More

recently, however, many historians have tended once again to view the

Battle of Tours as a very significant event in the history of Europe

and Christianity. Equally, many, such as William Watson,

still believe this battle was one of macrohistorical world changing

importance, if they do not go so far as Gibbon does rhetorically. In the modern era, Matthew Bennett and his co-authors of "Fighting Techniques of the Medieval World",

published in 2005, argue that "few battles are remembered 1,000 years

after they are fought ... but the Battle of Poitiers, (Tours) is an

exception ... Charles Martel turned back a Muslim raid that had it been

allowed to continue, might have conquered Gaul." Michael Grant, author

of "History of Rome", grants the Battle of Tours such importance that he lists it in the macrohistorical dates of the Roman era. It

is important to note however that modern Western historians, military

historians, and writers, essentially fall into three camps. The first,

those who believe Gibbon was right in his assessment that Martel saved

Christianity and Western civilization by this battle are typified by

Bennett, Paul Davis, Robert Martin, and educationalist Dexter B. Wakefield who writes in An Islamic Europe. The

second camp of contemporary historians believe that a failure by Martel

at Tours could have been a disaster, destroying what would become

Western civilization after the Renaissance.

Certainly all historians agree that no power would have remained in

Europe able to halt Islamic expansion had the Franks failed. William E. Watson,

one of the most respected historians of this era, strongly supports

Tours as a macrohistorical event, but distances himself from the

rhetoric of Gibbon and Drubeck, writing, for example, of the battle's

importance in Frankish, and world, history in 1993: The

final camp of Western historians believe that the importance of the

battle is dramatically overstated. This view is typified by Alessandro

Barbero, who writes, "Today, historians tend to play down the

significance of the battle of Poitiers, pointing out that the purpose

of the Arab force defeated by Charles Martel was not to conquer the

Frankish kingdom, but simply to pillage the wealthy monastery of

St-Martin of Tours". Similarly, Tomaž Mastnak writes: However,

it is vital to note, when assessing Charles Martel's life, that even

those historians who dispute the significance of this one Battle as the

event that saved Christianity, do not dispute that Martel himself had a

huge effect on Western European history. Modern military historian Victor Davis Hanson acknowledges the debate on this battle, citing historians both for and against its macrohistorical placement: In

the subsequent decade, Charles led the Frankish army against the

eastern duchies, Bavaria and Alemannia, and the southern duchies, Aquitaine and Provence. He dealt with the ongoing conflict with the Frisians and Saxons to

his northeast with some success, but full conquest of the Saxons and

their incorporation into the Frankish empire would wait for his

grandson Charlemagne, primarily because Martel concentrated the bulk of

his efforts against Muslim expansion. So

instead of concentrating on conquest to his east, he continued

expanding Frankish authority in the west, and denying the Emirate of

Córdoba a foothold in Europe beyond Al-Andalus. After his

victory at Tours, Martel continued on in campaigns in 736 and 737 to

drive other Muslim armies from bases in Gaul after they again attempted

to get a foothold in Europe beyond Al-Andalus. Between his victory of 732 and 735, Charles reorganized the kingdom of Burgundy,

replacing the counts and dukes with his loyal supporters, thus

strengthening his hold on power. He was forced, by the ventures of Radbod, duke of the Frisians (719 - 734), son of the Duke Aldegisel who had accepted the missionaries Willibrord

and Boniface, to invade independence minded Frisia again in 734. In that year, he slew the duke, who had expelled the Christian

missionaries, in the battle of the Boarn and so wholly subjugated the populace (he destroyed every pagan shrine) that the people were peaceful for twenty years after. The

dynamic changed in 735 because of the death of Odo the Great, who had

been forced to acknowledge, albeit reservedly, the suzerainty of

Charles in 719. Though Charles wished to unite the duchy directly to

himself and went there to elicit the proper homage of the Aquitainians,

the nobility proclaimed Odo's son, Hunald of Aquitaine,

whose dukedom Charles recognised when the Umayyads invaded Provence the

next year, and who equally was forced to acknowledge Charles as

overlord as he had no hope of holding off the Muslims alone. This naval Arab invasion was headed by Abdul Rahman's son. It landed in Narbonne in 736 and moved at once to reinforce Arles and

move inland. Charles temporarily put the conflict with Hunold on hold,

and descended on the Provençal strongholds of the Umayyads. In 736, he retook Montfrin and Avignon, and Arles and Aix-en-Provence with the help of Liutprand, King of the Lombards. Nîmes, Agde, and Béziers,

held by Islam since 725, fell to him and their fortresses were

destroyed. He crushed one Umayyad army at Arles, as that force sallied

out of the city, and then took the city itself by a direct and brutal

frontal attack, and burned it to the ground to prevent its use again as

a stronghold for Umayyad expansion. He then moved swiftly and defeated

a mighty host outside of Narbonne at the River Berre, but failed to

take the city. Military historians believe he could have taken it, had

he chosen to tie up all his resources to do so — but he believed his life

was coming to a close, and he had much work to do to prepare for his

sons to take control of the Frankish realm. A direct frontal assault,

such as took Arles, using rope ladders and rams, plus a few catapults,

simply was not sufficient to take Narbonne without horrific loss of

life for the Franks, troops Martel felt he could not lose. Nor could he

spare years to starve the city into submission, years he needed to set

up the administration of an empire his heirs would reign over. He left

Narbonne therefore, isolated and surrounded, and his son would return

to liberate it for Christianity. Notable about these campaigns was Charles' incorporation, for the first time, of heavy cavalry with stirrups to augment his phalanx.

His ability to coordinate infantry and cavalry veterans was unequaled

in that era and enabled him to face superior numbers of invaders, and

to decisively defeat them again and again. Some historians believe the

Battle against the main Muslim force at the River Berre, near Narbonne,

in particular was as important a victory for Christian Europe as Tours.

In Barbarians, Marauders, and Infidels, Antonio Santosuosso, Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Western Ontario,

and considered an expert historian in the era in dispute, puts forth an

interesting modern opinion on Martel, Tours, and the subsequent

campaigns against Rahman's son in 736 - 737. Santosuosso presents a

compelling case that these later defeats of invading Muslim armies were

at least as important as Tours in their defence of Western Christendom

and the preservation of Western monasticism, the monasteries of which were the centers of learning which ultimately led Europe out of her Middle Ages.

He also makes a compelling argument, after studying the Arab histories

of the period, that these were clearly armies of invasion, sent by the

Caliph not just to avenge Tours, but to begin the conquest of Christian

Europe and bring it into the Caliphate. Further,

unlike his father at Tours, Rahman's son in 736 - 737 knew that the

Franks were a real power, and that Martel personally was a force to be

reckoned with. He had no intention of allowing Martel to catch him

unawares and dictate the time and place of battle, as his father had,

and concentrated instead on seizing a substantial portion of the

coastal plains around Narbonne in 736 and heavily reinforced Arles as

he advanced inland. They planned from there to move from city to city,

fortifying as they went, and if Martel wished to stop them from making

a permanent enclave for expansion of the Caliphate, he would have to

come to them, in the open, where, he, unlike his father, would dictate

the place of battle. All worked as he had planned, until Martel

arrived, albeit more swiftly than the Moors believed he could call up

his entire army. Unfortunately for Rahman's son, however, he had

overestimated the time it would take Martel to develop heavy cavalry

equal to that of the Muslims. The Caliphate believed it would take a

generation, but Martel managed it in five short years. Prepared to face

the Frankish phalanx, the Muslims were totally unprepared to face a

mixed force of heavy cavalry and infantry in a phalanx. Thus, Charles

again championed Christianity and halted Muslim expansion into Europe,

as the window was closing on Islamic ability to do so. These defeats,

plus those at the hands of Leo in Anatolia were the last great attempt

at expansion by the Umayyad Caliphate before the destruction of the

dynasty at the Battle of the Zab,

and the rending of the Caliphate forever, especially the utter

destruction of the Umayyad army at River Berre near Narbonne in 737. In 737, at the tail end of his campaigning in Provence and Septimania, the king, Theuderic IV, died. Martel, titling himself maior domus and princeps et dux Francorum, did not appoint a new king and nobody acclaimed one. The throne lay vacant until Martel's death. As the historian Charles Oman says (The Dark Ages, pg 297), "he cared not for name or style so long as the real power was in his hands." Gibbon

has said Martel was "content with the titles of Mayor or Duke of the

Franks, but he deserved to become the father of a line of kings," which

he did. Gibbon also says of him, "in the public danger, he was summoned

by the voice of his country." The

interregnum, the final four years of Charles' life, was more peaceful

than most of it had been and much of his time was now spent on

administrative and organisational plans to create a more efficient

state. Though, in 738, he compelled the Saxons of Westphalia to

do him homage and pay tribute, and in 739 checked an uprising in

Provence, the rebels being under the leadership of Maurontus. Charles

set about integrating the outlying realms of his empire into the

Frankish church. He erected four dioceses in Bavaria (Salzburg, Regensburg, Freising, and Passau) and gave them Boniface as archbishop and metropolitan over all Germany east of the Rhine, with his seat at Mainz.

Boniface had been under his protection from 723 on; indeed the saint

himself explained to his old friend, Daniel of Winchester, that without

it he could neither administer his church, defend his clergy, nor

prevent idolatry. It was Boniface who had defended Charles most stoutly

for his deeds in seizing ecclesiastical lands to pay his army in the

days leading to Tours, as one doing what he must to defend

Christianity. In 739, Pope Gregory III begged

Charles for his aid against Liutprand, but Charles was loath to fight

his onetime ally and ignored the Papal plea. Nonetheless, the Papal

applications for Frankish protection showed how far Martel had come

from the days he was tottering on excommunication, and set the stage

for his son and grandson to rearrange Italian political boundaries to

suit the Papacy, and protect it. Charles Martel died on October 22, 741, at Quierzy-sur-Oise in what is today the Aisne département in the Picardy region of France. He was buried at Saint Denis Basilica in Paris. His territories were divided among his adult sons a year earlier: to Carloman he gave Austrasia and Alemannia (with Bavaria as a vassal), to Pippin the Younger Neustria and Burgundy (with Aquitaine as a vassal), and to Grifo nothing, though some sources indicate he intended to give him a strip of land between Neustria and Austrasia. Gibbon

called him "the hero of the age" and declared "Christendom ...

delivered ... by the genius and good fortune of one man, Charles Martel." At

the beginning of Charles Martel's career, he had many internal

opponents and felt the need to appoint his own kingly claimant,

Clotaire IV. By his end, however, the dynamics of rulership in Francia

had changed, no hallowed Meroving was needed, neither for defence nor

legitimacy: Charles divided his realm between his sons without

opposition (though he ignored his young son Bernard).

In between, he strengthened the Frankish state by consistently

defeating, through superior generalship, the host of hostile foreign

nations which beset it on all sides, including the non-Christian

Saxons, which his grandson Charlemagne would fully subdue, and Moors, which he halted on a path of continental domination. Though he never cared about titles, his son Pippin did, and finally asked the Pope "who

should be King, he who has the title, or he who has the power?" The

Pope, highly dependent on Frankish armies for his independence from

Lombard and Byzantine power (the Byzantine Emperor still considered himself to be the only legitimate "Roman Emperor", and thus, ruler of all of the provinces of the ancient empire, whether recognised or not), declared for "he who had the power" and immediately crowned Pippin. Decades later, in 800, Pippin's son Charlemagne was

crowned emperor by the Pope, further extending the principle by

delegitimising the nominal authority of the Byzantine Emperor in the

Italian peninsula (which had, by then, shrunk to encompass little more

than Apulia and Calabria at best) and ancient Roman Gaul, including the Iberian outposts Charlemagne had established in the Marca Hispanica across the Pyrenees, what today forms Catalonia. In short, though the Byzantine Emperor claimed authority over all the old Roman Empire, as the legitimate "Roman" Emperor, it was simply not reality. The bulk of the Western Roman Empire had

come under Carolingian rule, the Byzantine Emperor having had almost no

authority in the West since the sixth century, though Charlemagne, a

consummate politician, preferred to avoid an open breach with

Constantinople. An institution unique in history was being born: the Holy Roman Empire. Though the sardonic Voltaire ridiculed

its nomenclature, saying that the Holy Roman Empire was "neither Holy,

nor Roman, nor an Empire," it constituted an enormous political power

for a time, especially under the Saxon and Salian dynasties and, to a lesser, extent, the Hohenstaufen.

It lasted until 1806, by which time it was a nonentity. Though his

grandson became its first emperor, the "empire" such as it was, was

largely born during the reign of Charles Martel. Charles was that rarest of commodities in the Middle Ages: a brilliant strategic general, who also was a tactical commander par excellence, able in the heat of battle to adapt his plans to his foe's forces and

movement — and amazingly, to defeat them repeatedly, especially when,

as at Tours, they were far superior in men and weaponry, and at Berre

and Narbonne, when they were superior in numbers of fighting men.

Charles had the last quality which defines genuine greatness in a

military commander: he foresaw the dangers of his foes, and prepared

for them with care; he used ground, time, place, and fierce loyalty of

his troops to offset his foe's superior weaponry and tactics; third, he

adapted, again and again, to the enemy on the battlefield, shifting to

compensate for the unforeseen and unforeseeable. Gibbon,

whose tribute to Martel has been noted, was not alone among the great

mid era historians in fervently praising Martel; Thomas Arnold ranks

the victory of Charles Martel even higher than the victory of Arminius in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in its impact on all of modern history: German

historians are especially ardent in their praise of Martel and in their

belief that he saved Europe and Christianity from then all conquering

Islam, praising him also for driving back the ferocious Saxon

barbarians on his borders. Schlegel speaks of this "mighty victory" in

terms of fervent gratitude, and tells how " the arm of Charles Martel

saved and delivered the Christian nations of the West from the deadly

grasp of all destroying Islam", and Ranke points out, In 1922 and 1923, Belgian historian Henri Pirenne published

a series of papers, known collectively as the "Pirenne Thesis", which

remain influential to this day. Pirenne held that the Roman Empire

continued, in the Frankish realms, up until the time of the Arab conquests in

the 7th century. These conquests disrupted Mediterranean trade routes

leading to a decline in the European economy. Such continued disruption

would have meant complete disaster except for Charles Martel's halting

of Islamic expansion into Europe from 732 on. What he managed to

preserve led to the Carolingian Renaissance, named after him. Professor Santosuosso perhaps

sums up Martel best when he talks about his coming to the rescue of his

Christian allies in Provence, and driving the Muslims back into the

Iberian Peninsula forever in the mid and late 730s: In the Netherlands, a vital part of the Carolingian Empire, and elsewhere in the Low Countries, he is considered a hero. In France and Germany, he is revered as a hero of epic proportions. Skilled

as an administrator and ruler, Martel organized what would become the

medieval European government: a system of fiefdoms, loyal to barons,

counts, dukes and ultimately the King, or in his case, simply maior domus and princeps et dux Francorum.

("First or Dominant Mayor and Prince of the Franks") His close

coordination of church with state began the medieval pattern for such

government. He created what would become the first western standing

army since the fall of Rome by his maintaining a core of loyal veterans

around which he organized the normal feudal levies. In essence, he

changed Europe from a horde of barbarians fighting with one another, to

an organized state. Although it took another two decades for the Franks to drive all the Arab garrisons out of Septimania and across the Pyrenees,

Charles Martel's halt of the invasion of French soil turned the tide of

Islamic advances, and the unification of the Frankish kingdoms under

Martel, his son Pippin the Younger, and his grandson Charlemagne

created a western power which prevented the Emirate of Córdoba

from expanding over the Pyrenees. Martel, who in 732 was on the verge

of excommunication, instead was recognised by the Church as its

paramount defender. Pope Gregory II wrote him more than once, asking his protection and aid, and he remained, till his death, fixated on stopping the Muslims. Martel's son Pippin the Younger kept his father's promise and returned and took Narbonne by siege in 759. His grandson, Charlemagne, actually established the Marca Hispanica across the Pyrenees in part of what today is Catalonia, reconquering Girona in 785 and Barcelona in

801. Carolingians called this region of modern day Spain "The Moorish

Marches", and saw it as more than a simple check on the Muslims in

Hispania. It formed a permanent buffer zone against Islam and became the basis, along with the efforts of Pelayo (Latin: Pelagius) and his descendants, for the Reconquista. Victor Davis Hanson argues that Charles Martel launched "the thousand year struggle" between European heavy infantry and Muslim cavalry. Of

course, Martel is also the father of heavy cavalry in Europe, as he

integrated heavy armoured cavalry into his forces. This creation of a

real army would continue all through his reign, and that of his son,

Pepin the Short, until his Grandson, Charlemagne, would possess the

world's largest and finest army since the peak of Rome. Equally,

the Muslims used infantry - indeed, at the Battle of Toulouse most of

their forces were light infantry. It was not till Abdul Rahman Al

Ghafiqi brought a huge force of Arab and Berber cavalry with him when

he assumed the emirate of Al-Andulus that the Muslim forces became

primarily cavalry. Martel's army was known primarily for being the first standing permanent army since Rome's fall in 476, " and

for the core of tough, seasoned heavy infantry who stood so stoutly at

Tours. The Frankish infantry wore as much as 70 pounds of armour,

including their heavy wooden shields with an iron boss. Standing close

together, and well disciplined, they were unbreakable at Tours. Martel

had taken the money and property he had seized from the church and paid

local nobles to supply trained ready infantry year round. This was the

core of veterans who served with him on a permanent basis, and as

Hanson says, "provided a steady supply of dependable troops year

around." While other Germanic cultures, such as the Visigoths or

Vandals, had a proud martial tradition, and the Franks themselves had

an annual muster of military aged men, such tribes were only able to

field armies around planting and harvest. It was Martel's creation of a

system whereby he could call on troops year round that gave the

Carolingians the first standing and permanent army since Rome's fall in

the west. And,

first and foremost, Charles Martel will always be remembered for his

victory at Tours. Creasy argues that the Martel victory "preserved the

relics of ancient and the germs of modern civilizations." Gibbon called

those eight days in 732, the week leading up to Tours, and the battle

itself, "the events that rescued our ancestors of Britain, and our

neighbors of Gaul [France], from the civil and religious yoke of the

Koran." Paul Akers, in his editorial on Charles Martel, says for those

who value life and freedom "you might spare a minute sometime today,

and every October, to say a silent 'thank you' to a gang of half savage

Germans and especially to their leader, Charles 'The Hammer' Martel." In

his vision of what would be necessary for him to withstand a larger

force and superior technology (the Muslim horsemen had adopted the

armour and accoutrements of heavy cavalry from the Sassanid Warrior

Class, which made the first knights possible), he, daring not to send

his few horsemen against the Islamic cavalry, used his army to fight in

a formation used by the ancient Greeks to

withstand superior numbers and weapons by discipline, courage, and a

willingness to die for their cause: a phalanx. He had trained a core of

his men year round, using mostly Church funds, and some had been with

him since his earliest days after his father's death. It was this hard

core of disciplined veterans that won the day for him at Tours. Hanson

emphasizes that Martel's greatest accomplishment as a General may have

been his ability to keep his troops under control. This absolute iron

discipline saved his infantry from the fate of so many infantrymen -

such as the Saxons at Hastings - who broke formation and were

slaughtered piecemeal. After using this infantry force by itself at

Tours, he studied the foe's forces and further adapted to them,

initially using stirrups and saddles recovered from the foe's dead

horses, and armour from the dead horsemen. The defeats Martel inflicted on the Muslims were vital in that the split in the Islamic world left the Caliphate unable

to mount an all out attack on Europe via its Iberian stronghold after

750. His ability to meet this challenge, until the Muslims

self-destructed, is considered by most historians to be of macrohistorical importance, and is why Dante writes of him in Heaven as one of the "Defenders of the Faith." H. G. Wells says of Charles Martel's decisive defeat of the Muslims in his "Short History of the World: John H. Haaren says in “Famous Men of the Middle Ages” Just

as his grandson, Charlemagne, would become famous for his swift and

unexpected movements in his campaigns, Charles was legendary for never

doing what his enemies forecast he would do. It was this ability to do

the unforeseen, and move far faster than his opponents believed he

could, that characterized the military career of Charles Martel. It

is notable that the Northmen did not begin their European raids until

after the death of Martel's grandson, Charlemagne. They had the naval

capacity to begin those raids at least three generations earlier, but

chose not to challenge Martel, his son Pippin, or his grandson,

Charlemagne. This was probably fortunate for Martel, who despite his

enormous gifts, would probably not have been able to repel the Vikings

in addition to the Muslims, Saxons, and everyone else he defeated.

However, it is notable that again, despite the ability to do so, (the

Danes had constructed defenses to defend from counterattacks by land,

and had the ability to launch their wholesale sea raids as early as

Martel's reign), they chose not to challenge Charles Martel. J.M. Roberts says of Charles Martel in his note on the Carolingians in his 1993 History of the World: Gibbon perhaps summarized Charles Martel's legacy most

eloquently: "in a laborious administration of 24 years he had restored

and supported the dignity of the throne.. by the activity of a warrior

who in the same campaign could display his banner on the Elbe, the

Rhone, and shores of the ocean."