<Back to Index>

- Philosopher Johann Adam Weishaupt, 1748

- Writer Irmgard Keun, 1905

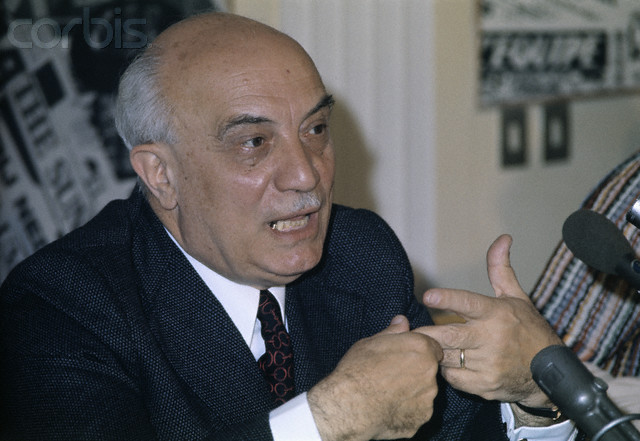

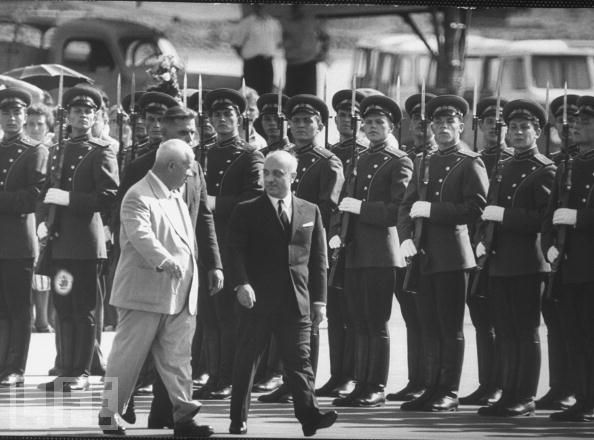

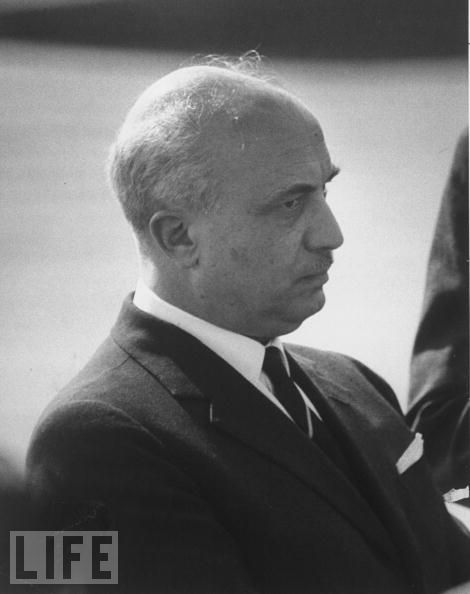

- Prime Minister of Italy Amintore Fanfani, 1908

PAGE SPONSOR

Amintore Fanfani (February 6, 1908 - November 20, 1999) was an Italian career politician and the 33rd man to serve the office of Prime Minister of the State. He was one of the well known Italian politicians after the Second World War, and a historical figure of the Christian Democracy (Italian: Democrazia Cristiana – DC).

Fanfani and Giovanni Giolitti are

still actually the sole men which became Prime ministers of Italy in

five different periods. However, the sum of the days of Fanfani's five

terms are 1571 (four years, 110 days), while Silvio Berlusconi spent 1801 days (four years, 340 days) at office in his second term only (2001 - 2006). Fanfani was one of the dominant figures of the Italian Christian Democrats for over three decades. Fanfani was born in Pieve Santo Stefano, in the province of Arezzo, Tuscany, to a large and humble family. He graduated in economics and business in 1932 from the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore in Milan.

He was the author of a number of important works on economic history

dealing with religion and the development of capitalism in the Renaissance and Reformation in Europe. His thesis was published in Italian and then in English as Catholicism, Capitalism and Protestantism in 1935. He joined the Italian fascist party supporting the corporatist ideas

of the regime promoting collaboration between the classes, which he

defended in many articles. "Some day," he once wrote, "the European

continent will be organized into a vast supranational area guided by

Italy and Germany. Those areas will take authoritarian governments and

synchronize their constitutions with Fascist principles." He also wrote for the official magazine of racism in Fascist Italy, The Defence of the Race (Italian: La difesa della razza). In 1938, he was among the 330 that signed the antisemitic Manifesto of Race (Italian: Manifesto della razza) – culminating in laws that stripped the Italian Jews of Italian citizenship and with it any position in the government or professions which many previous had. During the years he spent in Milan, he knew Giuseppe Dossetti and Giorgio La Pira.

They formed a group known as the "little professors" who lived

ascetically in monastery cells and walked barefoot. They formed the

nucleus of Democratic Initiative, an intensely Catholic but

economically reformist wing of the post-war Christian Democratic Party, holding meetings to discuss Catholicism and society. After the surrender of Italy with the Allied armed forces on September 8, 1943, the group disbanded. Until the Liberation in April 1945, Fanfani fled to Switzerland dodging military service, and organized university courses for refugee Italians. Upon

his return to Italy, he was elected vice-secretary of the newly founded

Christian Democratic Party. He was as one of the youngest party leaders

and a protégé of Alcide De Gasperi,

the undisputed leader of the party for the following decade. Fanfani

represented a particular ideological position, that of conservative

Catholics who favoured socio-economic interventionism, which was very

influential in the 1950s and 1960s but which gradually lost its appeal.

"Capitalism requires such a dread of loss," he once wrote, "such a

forgetfulness of human brotherhood, such a certainty that a man's

neighbour is merely a customer to be gained or a rival to be

overthrown, and all these are inconceivable in the Catholic conception

... There is an unbridgeable gulf between the Catholic and the

capitalist conception of life." Private economic initiative, in his view, was justifiable only if harnessed to the common good. He was elected to the Constituent Assembly,

and was a member of the Commission that drafted the text of the new

Republican Constitution. The first article of the new constitution

reflected Fanfani's philosophy. He proposed an article, which read:

"Italy is a democratic republic founded on work." In 1948 he was

elected to the Italian Chamber of Deputies. Under

de Gasperi, Fanfani took on a succession of ministries. He was Minister

of Labour from 1947 – 1948 and again from 1948 – 1950; Minister of

Agriculture from 1951 – 1953; as well as Minister of the Interior in 1953

in the caretaker government of Giuseppe Pella. As Minister of Labour, he developed the "Fanfani house" program for

government built workers' homes and put 200,000 of Italy's many

unemployed to work on a reforestation program. As Minister of

Agriculture, he set in motion much of the Christian Democrats' land

reform program. "He

can keep going for 36 hours on catnaps, apples and a few sips of

water," according to a news report in Time Magazine. Once, when someone

proposed Fanfani for yet another ministry, De Gasperi refused. "If I

keep on appointing Fanfani to various ministries, I am sure that one of

these days I will open the door to my study and find Fanfani sitting at

my desk," he said. After

De Gasperi's retirement in 1953 Fanfani emerged as the anticipated

successor, a role confirmed by his appointment as party secretary from

1954 - 1959. He

reorganized and rejuvenated the national party organization of the

Christian Democrats after the dependence on the church and the

government which had typified the De Gasperi period.

However,

his activist and sometimes authoritarian style, as well as his

reputation as an economic reformer, ensured that the moderates within

the DC, who opposed the state’s intrusion into the country’s economic

life, regarded him with distrust. His indefatigable energy and his

passion for efficiency carried him far in politics, but he was rarely

able to exploit fully the opportunities that he created. "Fanfani has

colleagues, associates, acquaintances and subordinates," one politician

once remarked. "But I have never heard much about his friends." After

the death of De Gasperi, from 1954 to the mid 1960s Fanfani's weight

both in the party and in national politics was at its height. He served

as Prime Minister in several governments, some of them short lived.

His first government in 1954 lasted only 21 days when it failed to win

approval in the Parliament. As Minister of the Interior, with orders to step up measures against Communist subversion, Fanfani had named young (35) Giulio Andreotti, another protégé of De Gasperi. He

became head of government again from July 1958 to January 1959, when

his steamroller tactics lost him the support of his own Christian

Democratic colleagues. He

learned from the experience, and became wiser in the ways of

cooperating and compromising. From July 1960 to February 1962, from

February 1962 to May 1963, he was Prime Minister once more, securing

the support of the Italian Socialist Party (Italian: Partito Socialista Italiano, PSI), thus involving the centre-left in Italian politics. He had been a leading proponent of such an "opening to the centre-left" for years. The opportunity arose when a liberal Pope, John XXIII,

was elected in 1958, and the Socialists loosened their ties with the

Communists. In February 1962 he reorganised his cabinet and gained the

benign abstention of the PSI leader Pietro Nenni. But

he was too powerful to be allowed to be the Prime Minister of the first

such government, which actually included the Socialists, and it was instead headed by Aldo Moro. He

failed to become president of the Republic in 1964, and for much of the

1960s he was forced in the background. A strong supporter of the European Economic Community (EEC), Fanfani was foreign minister in 1965 and in 1966 - 68. He also served (1965 – 66) as president of the United Nations General Assembly -

he is the only Italian to have held this office. In 1971 he was again

his party's candidate for the presidency, but in the secret ballot a

sizeable number of his own party colleagues failed to support him. As a

consolation, he was made Senator for life in 1972. He

was President of the Senate from 1968 to 1973. Fanfani became secretary

of the Christian Democrats for a second time in 1973. As such, he led

the campaign for the referendum on repealing the law allowing divorce,

which he fought in typically combative style, alienating the

pro-divorce groups unnecessarily, without achieving the victory that

would have given him predominance in his own party. The

defeat of the divorce referendum provoked his resignation as party

secretary in 1975. He had to content himself with the status of

President of the Senate, formally the second office of the state. In

the later part of his career his aspiration was to be elected President

of the Republic, but, notwithstanding the formal party nomination, he

never secured the sufficient support in the electoral college. From

1982 to 1983, Fanfani was Prime Minister for a fifth time. From 1985 to

1987, he was President of the Senate again. From April to July 1987, he

was Prime Minister for the sixth time. Fanfani was elected to the

prestigious post of chairman of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the

Senate from 1994 - 1996. Fanfani died in Rome on

November 20, 1999. He saw the corporate state as the ideal, and in what

he calls a "temporary aberration" turned to Fascism. He has never tried

to hide his Fascist record; but unlike many of his countrymen, he

freely admits that he was wrong. He

held all positions and offices a politician could possibly aspire to,

except the one he craved most: president of the Republic. The

factionalism of the DC turned out to be the biggest obstacle to the

emergence of Fanfanismo, the pale Italian version of Gaullism, and one by one he lost his offices.