<Back to Index>

- Inventor John Deere, 1804

- Writer Laura Elizabeth Ingalls Wilder, 1867

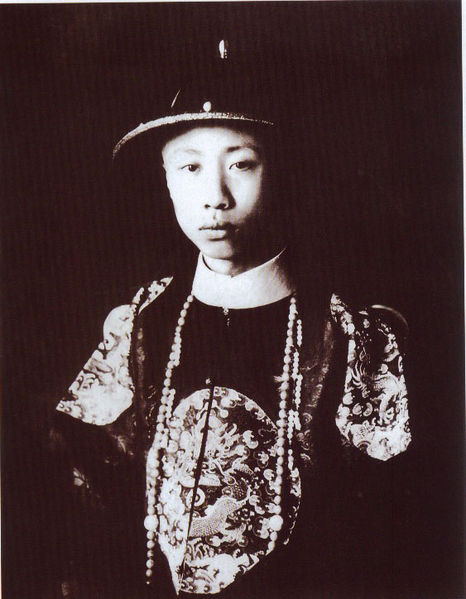

- Emperor of China Aisin Gioro Pŭ Yí, 1906

PAGE SPONSOR

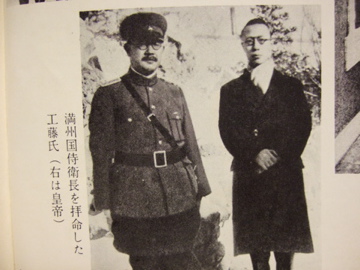

Aisin-Gioro Puyi (simplified Chinese: 溥仪; traditional Chinese: 溥儀; pinyin: Pǔ yí) (7 February 1906 – 17 October 1967), of the Manchu Aisin Gioro ruling family, was the last Emperor of China. He ruled in two periods between 1908 and 1917, firstly as the Xuantong Emperor (宣統皇帝) from 1908 to 1912, and nominally as a non-ruling puppet emperor for twelve days in 1917. He was the twelfth and final member of the Qing Dynasty to rule over China proper.

He was married to the Empress Gobulo Wan Rong under the suggestion of the Imperial Dowager Concubine Duan-Kang. Later, between 1934 and 1945, he was the Kangde Emperor (康德皇帝) of Manchukuo. In the People's Republic of China, he was a member of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference from 1964 until his death in 1967. His abdication was a symbol of the end of a long era in China, and he is widely known as The Last Emperor (末代皇帝). However Yuan Shikai, the first President of the Republic of China later claimed the title of "Emperor of China".

In English, he is known more simply as Puyi (P'u-i in Wade-Giles romanization), which is in accordance with the Manchu tradition of never using an individual's clan name and given name together, but is in complete contravention of the traditional Chinese and Manchu custom whereby the private given name of an emperor was considered taboo and

ineffable. It may be that the use of the given name Puyi after the

overthrow of the empire was thus a political technique, an attempt to

express desecration of the old order. After Puyi lost his imperial

title in 1924 he was officially styled "Mr. Puyi" (溥儀先生 Pǔyí Xiānsheng) in China. His clan name Aisin-Gioro was seldom used. He is also known to have used the name "Henry", a name chosen with his English language teacher, Scotsman Reginald Johnston. However,

the name Henry was merely used in communication with Westerners between

1920 and 1932, and was never used or was public knowledge in China. Puyi's great-grandfather was the Daoguang Emperor (r.1820 – 1850), who was succeeded by his fourth son, who became Xianfeng Emperor (r.1850 – 1861). Puyi's paternal grandfather was the 1st Prince Chun (1840 – 1891)

who was himself a son of the Daoguang Emperor and a younger

half-brother of Xianfeng Emperor, but not the next in line after

Xianfeng (the 1st Prince Chun had older half - brothers that were closer

in age to Xianfeng). Xianfeng was succeeded by his only son, who became

the Tongzhi Emperor (r.1861 - 1875). Tongzhi died without a son, and was succeeded by Guangxu Emperor (r.1875 – 1908), the son of the 1st Prince Chun and his wife, who was the younger sister of Empress Dowager Cixi. Guangxu died without an heir. Puyi, who succeeded Guangxu, was the eldest son of the 2nd Prince Chun (1883 – 1951), who was the son of the 1st Prince Chun and his second concubine, the Lady Lingiya (1866 – 1925). Lady Lingiya was a maid at the mansion of the 1st Prince Chun whose

original Chinese family name was Liu (劉); this was changed into the

Manchu clan's name Lingyia when she was made a Manchu, a requirement

before becoming the concubine of a Manchu prince. The 2nd Prince Chun was, therefore, a younger half-brother of the Guangxu Emperor and the first brother in line after Guangxu. Puyi was in a branch of the imperial family with close ties to Cixi, who was herself from the (Manchu) Yehe - Nara clan (the imperial family were the Aisin Gioro clan). Cixi married the daughter of her brother to her nephew Guangxu, who became, after Guangxu and Cixi's death, the Empress Dowager Longyu (1868 – 1913). Puyi's second cousin, Pu Xuezhai (溥雪齋), was an important master of the guqin musical instrument tradition and an artist of Chinese painting. Another brother, Pujie (1907 – 1994), married a cousin of Emperor Hirohito, Princess Hiro Saga, and changed the rules of succession to allow him to succeed his brother, who had no children. His last surviving (half-)brother Pu Ren (born 1918) still lives in China and has taken the Chinese name Jin Youzhi.

In 2006, Jin Youzhi filed a lawsuit in regards to the rights to Puyi's

image and privacy. The lawsuit claimed those rights were violated by

the exhibit "China's Last Monarch and His Family". Puyi's mother, the 2nd Princess Chun (1884 – 1921), given name Youlan (幼蘭), was the 2nd Prince Chun's wife. She was the daughter of the Manchu general Ronglu (榮祿) (1836 – 1903) from the Guwalgiya clan. Ronglu was one of the leaders of the conservative faction at the court, and a staunch supporter of Empress Dowager Cixi;

Cixi rewarded his support by marrying his daughter, Puyi's mother, into

the Imperial family. The Guwalgiya clan was regarded as one of the Qing

Dynasty's most powerful Manchu families. Oboi, a chief advisor to the Kangxi Emperor, was also from this clan. Chosen by Dowager Empress Cixi while on her deathbed, Puyi

ascended the throne aged 2 years and 10 months in December 1908

following his uncle's death on 14 November. He was titled the Xuantong Emperor.

Puyi's introduction to emperorship began when palace officials arrived

at his family household to take him. Puyi screamed and resisted as the

officials ordered the eunuchs to pick him up. His wet-nurse, Wen-Chao Wang, was the only one who could console him, and therefore accompanied Puyi to the Forbidden City. Puyi would not see his real mother again for seven years. Puyi

developed a special closeness with Wen-Chao Wang and credited her with

being the only person who could control him. She was sent away when he

was eight years old. After he married, he would occasionally bring her

to the Forbidden City, and later Manchukuo, to visit him. After his

special government pardon in 1959, he visited her adopted son and only

then learned of her personal sacrifices to be his nurse. Puyi's

upbringing was hardly conducive to the raising of a healthy,

well balanced child. Overnight, he was treated as a god and unable to

behave as a child. The adults in his life, save his wet-nurse Wen-Chao,

were all strangers, remote, distant, and unable to discipline him.

Wherever he went, grown men would kneel to the floor in a ritual kow-tow, averting their eyes until he passed. Soon the young Puyi discovered the absolute power he wielded over the eunuchs, and frequently had them beaten for small transgressions. Quotation of Puyi: After his marriage, Puyi began to take control of the palace. He described "an orgy of looting" taking place that involved "everyone from the highest to the lowest". According to Puyi, by the end of his wedding ceremony, the pearls and jade in the empress's crown had been stolen. Locks

were broken, areas ransacked, and on June 27, 1923 a fire destroyed the

area around the Palace of the Established Happiness. Puyi suspected it

was arson to cover theft. The emperor overheard conversations among the

eunuchs that made him fear for his life. In response, he evicted the

eunuchs from the palace. His

next plan of action was to reform the Household Department, the

officials of which he charged became so wealthy from theft and graft

that they were able to run their own outside businesses. Puyi's father, the 2nd Prince Chun, served as a regent until 6 December 1911 when Empress Dowager Longyu took over in the face of the Xinhai Revolution. Empress

Dowager Longyu signed the "Act of Abdication of the Emperor of the

Great Qing" (《清帝退位詔書》) on 12 February 1912, following the Xinhai Revolution, under a deal brokered by Yuan Shikai (the great general of the army Beiyang) with the imperial court in Beijing (formerly Peking) and the republicans in southern China. Signed with the new Republic of China, Puyi was to retain his imperial title and be treated by the government of the Republic with the protocol attached to a foreign monarch. This was similar to Italy's Law of Guarantees (1870) which accorded the Pope certain honors and privileges similar to those enjoyed by the King of Italy. He and the imperial court were allowed to remain in the northern half of the Forbidden City (the Private Apartments) as well as in the Summer Palace.

A hefty annual subsidy of 4 million silver dollars was granted by the

Republic to the imperial household, although it was never fully paid

and was abolished after just a few years. The document is dated 26 December 1914. In 1917, the warlord general Zhang Xun (張勛) restored Puyi to his throne for twelve days from July 1 to July 12. Zhang ordered his army to keep their queues (long plaits or

"pigtails") to display loyalty to the emperor. During those 12 days,

one small bomb was dropped over the Forbidden City by a republican

plane, causing minor damage. This is considered the first aerial bombardment ever in Eastern Asia. The restoration failed due to extensive opposition across China, and the decisive intervention of another warlord general, Duan Qirui. Puyi was expelled from the Forbidden City in Beijing in 1924 by warlord Feng Yuxiang.

Following his expulsion from the Forbidden City,

Puyi spent a few days at the house of his father 2nd Prince Chun, and

then temporarily resided in the Japanese embassy for a year and a half. In 1925, he moved to the "Quiet Garden Villa" in the Japanese Concession in Tianjin. During this period, Puyi and his advisers Chen Baochen, Zheng Xiaoxu and Luo Zhenyu discussed

ways to restore Puyi as Emperor. Xiaoxu and Zhenyu favored enlisting

outside assistance, while Baochen opposed the idea. In September 1931, Puyi sent a letter to Japanese minister of war Jirō Minami stating his desire to be restored to the throne. He was visited by Japanese Kwantung Army espionage head Kenji Doihara who proposed establishing Puyi as head of a Manchurian state. In November 1931, Puyi and Zheng Xiaoxu traveled to Manchuria to complete plans for the puppet state of Manchukuo. The Chinese government ordered his arrest for treason, but were unable to breach the Japanese protection. Chen Baochen returned to Beijing where he died in 1935. On 1 March 1932, Puyi was installed by the Japanese as the ruler of Manchukuo, considered by most historians as a puppet state of Imperial Japan, under the reign title Datong

(大同). In 1934, he was officially crowned the emperor of Manchukuo under

the reign title Kangde (康德). He was constantly at odds with the

Japanese in private, though submissive in public. He resented being

"Head of State" and then "Emperor of Manchukuo" rather than being fully

restored as Qing Emperor. Puyi lived at Wei Huang Gong in

this period. At his enthronement he clashed with Japan over dress; they

wanted him to wear a Manchukuoan uniform whereas he considered it an

insult to wear anything but traditional Qing Dynasty robes. In a typical compromise, he wore a Western military uniform to his enthronement (the only Chinese emperor ever to do so) and dragon robes to the announcement of his accession at the Altar of Heaven. His brother Pujie, who married Hiro Saga, a distant cousin to the Japanese Emperor Hirohito, was proclaimed heir apparent. The marriage had been politically arranged by Shigeru Honjō,

general of the Kwantung Army. Puyi thereafter would not speak candidly

in front of his brother and refused to eat any food provided by Hiro

Saga. Puyi was forced to sign an agreement that if he himself had a

male heir, the child would be sent to Japan to be raised by the

Japanese. From 1935 - 1945, Kwangtung Army senior staff officer Yasunori Yoshioka was

assigned to Puyi as Attaché to the Imperial Household in

Manchukuo. He acted as a spy for the Japanese government, controlling

Puyi through fear, intimidation, and direct orders. There were many attempts on Puyi's life during this period, including a 1937 stabbing by a palace servant. During Puyi's reign as Emperor of Manchukuo, his household was closely watched by the Japanese who increasingly took steps toward the full Japanization of

Manchuria, to prevent him from becoming too independent. He was feted

by the Japanese populace during his visits there, but had to remain subservient to Hirohito. It

is unclear whether the adoption of ancient Chinese styles and rites

such as using "His Majesty" instead of his real name were the product

of Puyi's interest or a Japanese imposition of their own imperial house

rules. During these years, he began taking a greater interest in traditional Chinese law and religion (e.g. Confucianism and Buddhism),

but this was disallowed by the Japanese. Slowly, his old supporters

were eliminated and pro-Japanese ministers put in their place. During

this period, his life consisted mostly of signing laws prepared by

Japan, reciting prayers, consulting oracles, and making formal visits

throughout his kingdom. At the end of World War II, Puyi was captured by the Soviet Red Army on 16 August 1945 while he was in an aeroplane fleeing to Japan. The Soviet army took him to the Siberian town of Chita. He lived in a sanatorium, but was later taken to Khabarovsk near the Chinese border. In 1946, he testified at the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in Tokyo. There he was scathing in his resentment of how he had been treated by the Japanese. When the Chinese Communists under Mao Zedong came to power in 1949, Puyi was repatriated to China after negotiations between the USSR and China. Puyi spent ten years in a Fushun War Criminals Management Centre, except during the Korean War he was taken to Harbin where he spent three years until 1954 because Fushun was near the Korean border, in Liaoning province until he was declared reformed. Puyi came to Beijing in 1959 with special permission from Chairman Mao Zedong and

lived the next six months in an ordinary Beijing residence with his

sister before being transferred to a government sponsored hotel. He

voiced his support for the Communists and worked at the Beijing

Botanical Gardens. He married Li Shuxian,

a hospital nurse, on 30 April 1962, in a ceremony held at the Banquet

Hall of the Consultative Conference. He subsequently worked as an

editor for the literary department of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference, where his monthly salary was around 100 Yuan of the Conference, an office in which he served from 1964 until his death. With encouragement from Mao and then Premier Zhou Enlai, and openly endorsed by the Government, Puyi wrote his autobiography(我的前半生 — "The first half of my life", translated in English as From Emperor to Citizen)

in the 1960s alongside Li Wenda, an editor of Beijing's People

Publishing Bureau. In the Oxford University edition of the book, in the

chapter I Refuse to Admit My Guilt, he made this statement regarding his false testimony at the Tokyo war crimes trial: I

now feel very ashamed of my testimony, as I withheld some of what I

knew to protect myself from being punished by my country. I said

nothing about my secret collaboration with the Japanese imperialists

over a long period, an association to which my open capitulation after

September 18, 1931 was but the conclusion. Instead, I spoke only of the

way the Japanese had put pressure on me and forced me to do their will. I

maintained that I had not betrayed my country but had been kidnapped;

denied all my collaboration with the Japanese; and even claimed that

the letter I had written to Jirō Minami was a fake. I covered up my crimes in order to protect myself. Mao began the Cultural Revolution in 1966, and the youth militia known as the Red Guards saw

Puyi, who symbolized Imperial China, as an easy target of attack. Puyi

was placed under protection by the local public security bureau,

although his food rations, salary, and various luxuries, including his

sofa and desk, were removed. Puyi became affected physically and

emotionally. He died in Beijing of complications arising from kidney cancer and heart disease on 17 October 1967. In accordance to the laws of the People's Republic of China at the time, Puyi's body was cremated. His ashes were first placed at the Babaoshan Revolutionary Cemetery, alongside those of other party and state dignitaries (before the establishment of the People's Republic of China this was the burial ground of Imperial concubines and eunuchs). In

1995, as a part of a commercial arrangement, Puyi's widow transferred

his ashes to a new commercial cemetery in return for monetary support.

The cemetery is located near the Western Qing Tombs (清西陵), 120 km (75 miles) southwest of Beijing,

where four of the nine Qing emperors preceding him are interred, along

with three empresses, and 69 princes, princesses, and imperial

concubines. Quotation of Puyi (referring to only the first four wives): In

1921, it was decided by the High Consorts that it was time for the

15-year-old Puyi to be married, although court politics dragged the

complete process (from selecting the bride, up through the wedding

ceremony) out for almost two years. Puyi saw marriage as his coming of

age benchmark, when others would no longer control him. He was given

four photographs to choose from. Puyi stated they all looked alike to

him, with the exception of different clothing. He chose Wen Xiu.

Political factions within the palace made the actual choice as to whom

Puyi would marry. The selection process alone took an entire year.

Puyi's second choice, a Manchu named Wan Rong (1906 – 1946, a.k.a. Radiant Countenance), became the Empress.

She was considered beautiful and came from a wealthy family. By his own

account, he abandoned Wan Rong in the bridal chamber and went back to

his own room. He

maintained that she was willing to be a wife in name only, in order to

carry the title of Empress. He placed blame for consort Wen Xiu's 1931

departure on Wan Rong and quit speaking to her or acknowledging her

presence. She became addicted to opium, and died in a prison at Tumen. His first choice for wife was Wen Xiu (1909 – 1950),

whom court officials deemed from an unacceptable impoverished family

and not beautiful enough to be an Empress; Wen Xiu was designated as a

concubine, and eventually sued for divorce in 1931. Puyi awarded her a

house in Beijing and $300,000 in alimony, to be provided by the

Japanese. In

his autobiography, Pu Yi stated her reason for the divorce was the

emptiness of life with him in exile, her desire for an ordinary family

life, and his own inability to see women as anything but slaves and

tools of men. Pu Yi related that she never re-married, became a primary

school teacher, and died in 1950.

His third wife was a Manchu, Tan Yuling, (1920 – 1942) a 16-year-old he married in 1937. He married her as "punishment" for Wan Rong, and, "...because a second wife was as essential as palace furniture." She

was also a wife in name only. She became ill in 1942 with typhoid,

which the Japanese occupation doctor said would not be fatal. After the

doctor's consultation with Attaché to the Imperial Household

Yasunori Yoshioka, Tan Yuling suddenly died. Puyi became suspicious of

the circumstances when the Japanese immediately offered him photographs

of Japanese girls for marriage.

In 1943, Puyi married his fourth wife, a 15-year-old student named Li Yuqin (1928 – 2001), a Han. In

February 1943, school principal Kobayashi and teacher Fujii of the

Nan-Ling Girls Academy took ten girl students to a photography studio

for portraits. Three weeks later, the school teacher and the principal

visited Li Yuqin's home and told her Puyi ordered her to go to the

Manchukuo palace to study. She was first taken directly to Yasunori

Yoshioka who thoroughly questioned her. Yoshioka then drove her back to

her parents and told them Puyi ordered her to study at the palace.

Money was promised to the parents. She was subjected to a medical

examination and then taken to Puyi's sister Yun-Ho and prepped on

palace protocol. Two

years later when Manchukuo collapsed, Li Yuqin shared a train with the

Empress who was going through opium withdrawal symptoms at the time.

They were both arrested by the Soviets and sent to a prison in Changchun. Li Yuqin was released in 1946 sent back to her home. She worked in a textile factory while she studied the works of Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin.

In 1955, she began visiting Puyi in prison. After applying to the

Chinese authorities for a divorce, the government responded on her next

prison visit by showing her to a room with a double bed and ordered her

to reconcile with Puyi, and she said the couple obeyed the order. She

divorced Puyi in 1958. She later married a technician, and had two sons.

In 1962, he married his fifth and last wife, a Han nurse, Li Shuxian (1925 – 1997), who survived him. She died of lung cancer in 1997. The Emperor had no children. She recounted that they dated for six months before the marriage, and she found him to be, "...a man who desperately needed my love and was ready to give me as much love as he could."

“ No

account of my childhood would be complete without mentioning the

eunuchs. They waited on me when I ate, dressed and slept; they

accompanied me on my walks and to my lessons; they told me stories; and

had rewards and beatings from me, but they never left my presence. They

were my slaves; and they were my earliest teachers. ”

“ ..they were not real wives and were only there for show ”