<Back to Index>

- Physician René Théophile Hyacinthe Laennec, 1781

- Composer Arcangelo Corelli, 1653

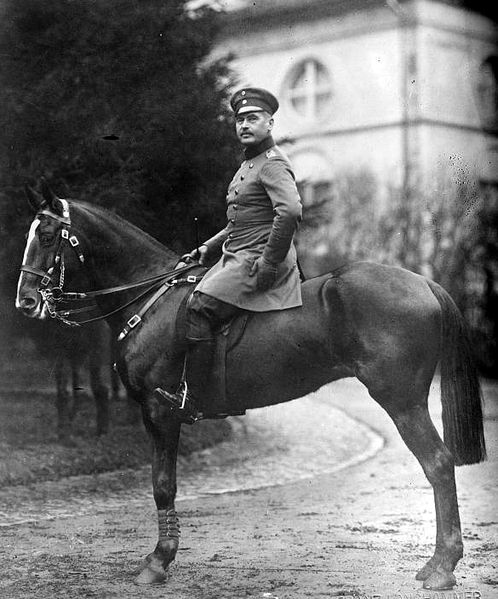

- General Otto Liman von Sanders, 1855

PAGE SPONSOR

Generalleutnant Otto Liman von Sanders (February 17, 1855 - August 22, 1929) was a German general who served as adviser and military commander for the Ottoman Empire during World War I.

He was born in Stolp in Pomerania region in Germany. His father was a Prussian nobleman. Like many other Prussians from aristocratic families, he joined the military and rose through the ranks to Lieutenant General. Like several Prussian generals before him (e.g., Von Moltke and Baron von der Goltz), he was appointed the head of a German military mission to the Ottoman Empire in 1913. For nearly eighty years, the Ottoman Empire had been trying to modernize their army along European lines. Liman von Sanders would be the last German to attempt this task.

Initially Liman formed a very low opinion of the Ottoman army and its political leadership. In July 1914 (with the war about to start), Enver Pasha offered an alliance, of a sort, with Germany. The German ambassador in Istanbul, Hans von Wangenheim, after consulting with Liman von Sanders, refused Enver's offer. The analysis was that the Ottoman army was weak, the government had little money to spend, and the leadership was incompetent. However, on 1 August 1914 the Germans and the Ottoman government did sign a secret treaty of alliance; included in the provisions of the treaty was that the German military mission would wield "effective influence" over the military operations of the Ottoman armies. At first, this influence was nearly zero. But when Enver Pasha and Djemal Pasha both suffered defeats, the German military mission took increasing control over the Ottoman armies.

When the Ottoman forces finally entered the war (after trying to avoid open conflict with the Alliance for two months), Enver Pasha showed Liman his grand scheme to destroy the Russian army defending Kars. Liman tried to dissuade Enver from implementing the plan, but his advice was ignored and Enver Pasha personally led the Ottoman army into its worst defeat of World War I at the Battle of Sarikamis. Cemal Pasha was given the task of attacking the Suez Canal; his personal military advisor was the German Friedrich Freiherr Kress von Kressenstein. The attack on the Suez also failed, although without enormous losses.

A shaken Enver Pasha returned to Istanbul and took command of the Ottoman army in the area around the capital. However immediately after a huge British and French fleet destroyed the Ottoman forts along the Dardanelles (18 March 1915), Enver turned over command to Liman von Sanders. Defending the Ottoman government was now in the hands of the German general.

Liman had little time to organize the defences, but he had two things in his favor. First, the Ottoman 5th Army was the best army they had, some 84,000 well-equipped soldiers in six divisions. Second, he was helped by poor Allied leadership. Instead of using their massive fleet to force a passage through the straits to Istanbul, the British and French admirals called for ground troops to capture the Dardanelles peninsula so their battleships could sail on into the Sea of Marmara unmolested. Liman had just over a month to prepare. Then, on 23 April 1915, the British landed a major force at Cape Helles. One of Liman's best decisions during this time was to promote Mustafa Kemal (later known as Atatürk) to commander of the 19th division. Kemal's division literally saved the day for the Ottomans. His troops marched up on the day of the invasion and occupied the ridge line above the ANZAC landing site, just as the ANZAC troops were moving up the slope themselves. Kemal recognized the danger and personally made sure his troops held the ridge line. They were never forced off despite constant attacks for the next five months.

From April to November 1915 (when the decision to evacuate was made), Liman had to fight off numerous attacks against his defensive positions. The British tried another landing at Suvla Bay, but this also was halted by the Ottoman defenders. The only bright spot for the British in this entire operation was that they managed to evacuate their positions without much loss. However, this battle was a major victory for the Ottoman army and some of the credit is given to the generalship of Liman von Sanders.

Early in 1915, the previous head of the German military mission to the Ottoman Empire, Baron von der Goltz arrived in Istanbul as military advisor to the (essentially powerless) Sultan, Mehmed V. The old Baron did not get along with Liman von Sanders and did not like the three Pashas (Enver Pasha, Cemal Pasha and Talat) who ran the Ottoman Empire during the war. The Baron proposed some major offensives against the British, but these proposals came to nothing in the face of Allied offensives against the Ottomans on three fronts (the Dardanelles, the Caucusus Front, and the newly opened Mesopotamian Front). Liman was rid of the old Baron when Enver Pasha sent him to fight the British in Mesopotamia in October 1915. (Goltz died there six months later just before the British army at Kut surrendered).

In 1918, the last year of the war, Liman von Sanders took over command of the Ottoman army in Palestine, replacing the German General Erich von Falkenhayn who had been defeated by British General Allenby at the end of 1917. Liman was hampered by the significant decline in power of the Ottoman army. His forces were unable to do anything more than occupy defensive positions and wait for the British attack. The attack was a long time in coming, but when General Allenby finally unleashed his army, the entire Ottoman army was destroyed in a week of fighting (see the Battle of Megiddo). In the rout, Liman was nearly captured by British soldiers.

After the war ended he was arrested in Malta in February 1919 on charges of having committed war crimes, but he was released six months later. He retired from the German army that year.

In

1927 he published a book he had written in captivity in Malta about his

experiences before and during the war (there is an English translation). Two years later Otto Liman von Sanders died in Munich at the age of seventy-four.