<Back to Index>

- Physicist Heinrich Rudolf Hertz, 1857

- Poet James Russell Lowell, 1819

- Shahanshah of Persia Tahmasp I, 1514

PAGE SPONSOR

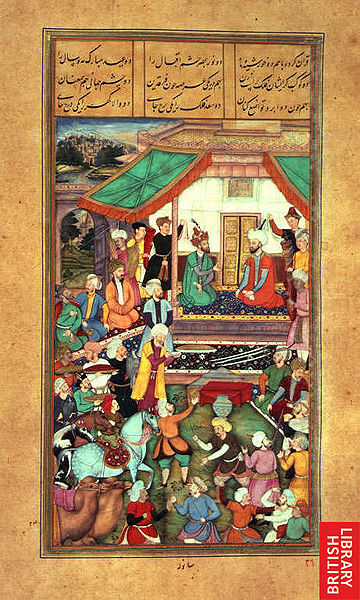

Tahmasp I (Persian: شاه تهماسب یکم) (February 22, 1514 – May 14, 1576) was an influential Shah of Iran, who enjoyed the longest reign of any member of the Safavid dynasty. He was the son of Ismail I and Shah-Begi Khanum (known under the title Tajlu Khanum) of the Turcoman Mawsillu tribe.

During his childhood he was weak and came under the control of the Qizilbash,

Turkic tribesmen who formed the backbone of Safavid power. The

Qizilbash leaders fought among themselves for the right to be regents

over Tahmasp. Upon adulthood, however, Tahmasp was able to reassert the

power of the Shah and control the tribesmen. His reign was marked by foreign threats, primarily from the Ottomans and the Uzbeks. In 1555, however, he regularized relations with the Empire through the Peace of Amasya. This peace lasted for 30 years, until it was broken in the time of Shah Mohammed Khodabanda. He is also known for the reception he gave to the fugitive Mughal Emperor Humayun which is depicted in a painting on the walls of the Safavid palace of Chehel Sotoon. One of Shah Tahmasp's more lasting achievements was his encouragement of the Persian rug industry on a national scale, possibly a response to the economic effects of the interruption of the Silk Road carrying trade during the Ottoman wars. Tahmasp was just 10 years old when he succeeded his father Shah Isma'il I, the founder of Safavid rule in Iran. Too young to rule in his own right, Tahmasp came under the control of the Qizilbash. Some of the tribes recognised a Qizilbash leader, Div Sultan Rumlu, as regent (atabeg)

to the shah, but others dissented and in 1526 a bloody civil war broke

out among the differing factions. Div Sultan emerged victorious but his

ally, Chuha Sultan Takkalu, turned against him and urged the shah to

get rid of him. On 5 July 1527 as Div Sultan arrived for a meeting of

the government, Tahmasp shot an arrow at him. When it failed to kill

him, the shah's supporters finished him off. Chuha Sultan now became regent. Iran's enemies, the Uzbeks, had taken advantage of the civil war to invade the north-eastern province of Khorasan.

In 1528 Chuha Sultan and the shah marched with their army to reassert

control of the region. Although they defeated the Uzbeks in a battle

near Jam, Tahmasp was disgusted at the cowardice Chuha Sultan had

displayed during the combat. Finally, in 1530/1, a quarrel broke out

between members of the Takkalu and Shamlu Qizilbash factions and the

Shamlus succeeded in killing Chuha Sultan. The Takkalus regained the

advantage and some of them even tried to kidnap the shah. Tahmasp lost

patience and ordered a general massacre of the Takkalu tribe. They

never regained their influence in Iran. The

leader of the Shamlu faction, Husayn Khan, now assumed the regency but,

in 1533, Tahmasp suspected Husayn Khan was plotting to overthrow him

and had him put to death. Tahmasp was now old enough and confident

enough to rule in his own right. The discord in Iran had allowed its enemies, the Uzbek khans in the east and the Ottoman Empirein the west, to seize territory. The Ottomans were at the height of their power during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent.

They launched four invasions of Iran between 1533 and 1553. Since the

Ottoman army possessed overwhelming numerical superiority, Tahmasp

avoided pitched battle with them and resorted to alternative tactics. In

1534, Suleiman invaded Iran with a force numbering 200,000 men and 300

pieces of artillery. Tahmasp could only field 7,000 men (of dubious

loyalty) and a few cannons. The Ottomans seized the Safavid capital Tabriz, crossed Kurdistan and captured Baghdad. Tahmasp avoided direct confrontation with the Ottoman army, preferring to harass it then retreat, leaving scorched earth behind him. This scorched earth policy led to the loss of 30,000 Ottoman troops as they made their way through the Zagros mountains and Suleiman decided to abandon his campaign. Next, Suleiman tried to exploit the disloyalty of Tahmasp's brother Alqas Mirza, who was governor of the frontier province of Shirvan.

Alqas had rebelled and, fearing his brother's wrath, he had fled to the

Ottoman court. He persuaded Suleiman that if he invaded the Iranians

would rise up and overthrow Tahmasp. In 1548, Suleiman and Alqas

entered Iran with a huge army but Tahmasp had already "scorched the

earth" around Tabriz and the Ottomans could find few supplies to

sustain themselves. Alqas penetrated further into Iran but the citizens

of Isfahan and Shiraz refused

to open their gates to him. He was forced to retreat to Baghdad where

the Ottomans abandoned him as an embarrassment. Captured by the

Iranians, his life was spared but he was condemned to spend the rest of

his life in prison in the fortress of Qahqaha. During the final Ottoman invasion of Iran in 1553, Tahmasp seized the initiative and defeated Iskandar Pasha near Erzerum. He also captured one of Suleiman's favourites, Sinan Beg. This persuaded the sultan to come to terms at the Peace of Amasya in

1555. The treaty freed Iran from Ottoman attacks for three decades.

Nevertheless, Tahmasp took the precaution of transferring his capital

from Tabriz to Qazvin, which was further away from the border. Between 1540 and 1553, Tahmasp conducted military campaigns in the Caucasus region, capturing many Armenians, Georgians and Circassians. These would become an important new element in Iranian society. The Mughal Empire was Iran's eastern neighbour. In 1544, the Mughal emperor, Humayun, fled to Tahmasp's court after he had been overthrown by the rebel Sher Shah Suri (Sher Khan). Tahmasp insisted on the Sunni Humayun converting to Shi'ism before he would help him. Humayun reluctantly agreed and also gave Tahmasp the strategically important city of Kandahar in

exchange for Iranian military assistance against the heirs of Sher Khan

and his own rebellious brothers. By 1555, he had regained his throne. Humayun

was not the only royal figure to seek refuge at Tahmasp's court. A

dispute arose in the Ottoman Empire over who was to succeed the aged

Suleiman the Magnificent. Suleiman's favourite wife, Roxelana, was eager for her eldest son Selim to

become the next sultan. But Selim was an alcoholic and Roxelana's third

son, Bayezid, had shown far greater military ability. The two princes

quarrelled and eventually Bayezid rebelled against his father. His

letter of remorse never reached Suleiman and he was forced to flee

abroad to avoid execution. In 1559, Bayezid arrived in Iran where

Tahmasp gave him a warm welcome. Suleiman was eager to negotiate his

son's return, but Tahmasp rejected his promises and threats until, in

1561, Suleiman offered him land and 400,000 gold pieces. In September

of that year, Tahmasp and Bayezid were enjoying a banquet at Tabriz

when Tahmasp suddenly pretended he had received news that the Ottoman

prince was engaged in a plot against his life. An angry mob gathered

and Tahmasp had Bayezid put into custody, alleging it was for his own

safety. Tahmasp then handed the prince over to the Ottoman ambassador.

Shortly afterwards, Bayezid was killed by agents sent by his own father. In

1574, Tahmasp fell ill and discord broke out among the Qizilbash once

more, this time over which prince was to succeed him. The shah's

Georgian and Circassian wives had also introduced a new faction into

the court. Seven of Tahmasp's surviving sons were by Georgian or

Circassian mothers and two by a Turcoman. Of the latter, Mohammed Khodabanda was regarded as unfit to rule because he was almost blind, and his younger brother, Ismail,

had been imprisoned by Tahmasp since 1555. Nevertheless, one court

faction supported Ismail, while another backed Haydar Mirza, the son of

a Georgian. Tahmasp himself was believed to favour Haydar but he

prevented his supporters from killing Ismail. Tahmasp

died as a result of poison, although it is unclear whether this was by

accident or on purpose. On his death, as expected, fighting broke out

between the different court factions. Haydar was killed and Ismail

emerged triumphant as Shah Ismail II.

Tahmasp

was an enthusiastic patron of the arts with a particular interest in

book illustration. The most famous example of such work is the Shāhnāma-yi Shāh Tahmāspī (King's Book of Kings), commissioned for Tahmasp by his father and containing 250 miniatures by the leading court artists of the era.