<Back to Index>

- Inventor Jacques de Vaucanson, 1709

- Painter Winslow Homer, 1836

- Fleet Admiral Chester William Nimitz, 1885

PAGE SPONSOR

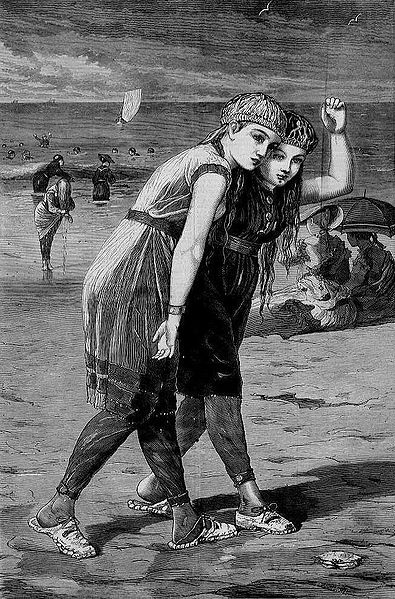

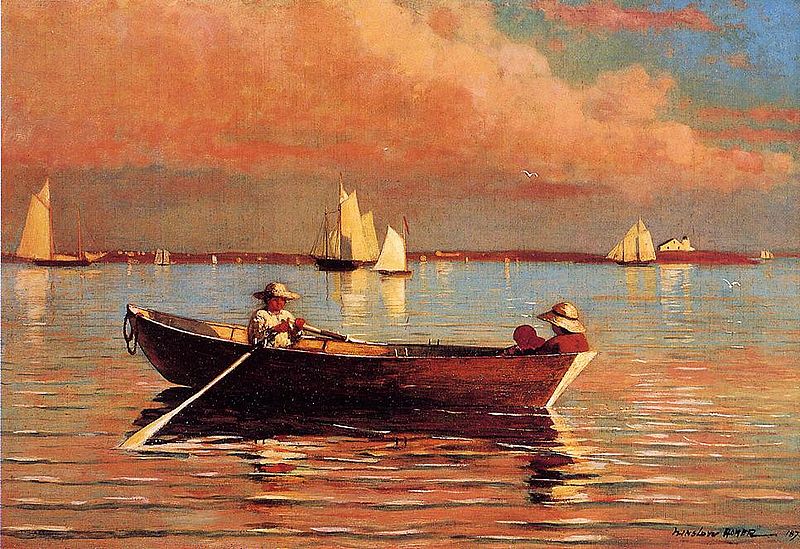

Winslow Homer (February 24, 1836 – September 29, 1910) was an American landscape painter and printmaker, best known for his marine subjects. He is considered one of the foremost painters in 19th century America and a preeminent figure in American art.

Largely self-taught, Homer began his career working as a commercial illustrator. He subsequently took up oil painting and produced major studio works characterized by the weight and density he exploited from the medium. He also worked extensively in watercolor, creating a fluid and prolific oeuvre, primarily chronicling his working vacations.

Born in Boston, Massachusetts, in

1836, Homer was the second of three sons of Charles Savage Homer and

Henrietta Benson Homer, both from long lines of New Englanders. His

mother was a gifted amateur watercolorist and Homer’s first teacher,

and she and her son had a close relationship throughout their lives.

Homer took on many of her traits, including her quiet, strong willed,

terse, sociable nature; her dry sense of humor; and her artistic talent. Homer had a happy childhood, growing up mostly in then rural Cambridge, Massachusetts. He was an average student, but his art talent was on display early. Homer’s

father was a volatile, restless businessman who was always looking to

“make a killing”. When Homer was thirteen, Charles gave up the hardware

store business to seek a fortune in the California gold rush.

When that failed, Charles left his family and went to Europe to raise

capital for other get-rich-quick schemes that didn’t materialize. After Homer’s high school graduation, his father saw an ad in the newspaper and arranged for an apprenticeship. Homer’s apprenticeship to a Boston commercial lithographer at the age of 19, was a formative but “treadmill experience”. He

worked repetitively on sheet music covers and other commercial work for

two years. By 1857, his freelance career was underway after he turned

down an offer to join the staff of Harper's Weekly.

“From the time I took my nose off that lithographic stone”, Homer later

stated, “I have had no master, and never shall have any.” Homer’s career as an illustrator lasted nearly twenty years. He contributed to magazines such as Ballou's Pictorial and Harper's Weekly, at a time when the market for illustrations was growing rapidly, and

when fads and fashions were changing quickly. His early works, mostly

commercial engravings of urban and country social scenes, are

characterized by clean outlines, simplified forms, dramatic contrast of

light and dark, and lively figure groupings — qualities that remained

important throughout his career. His quick success was mostly due to this strong understanding of graphic design and also to the adaptability of his designs to wood engraving.

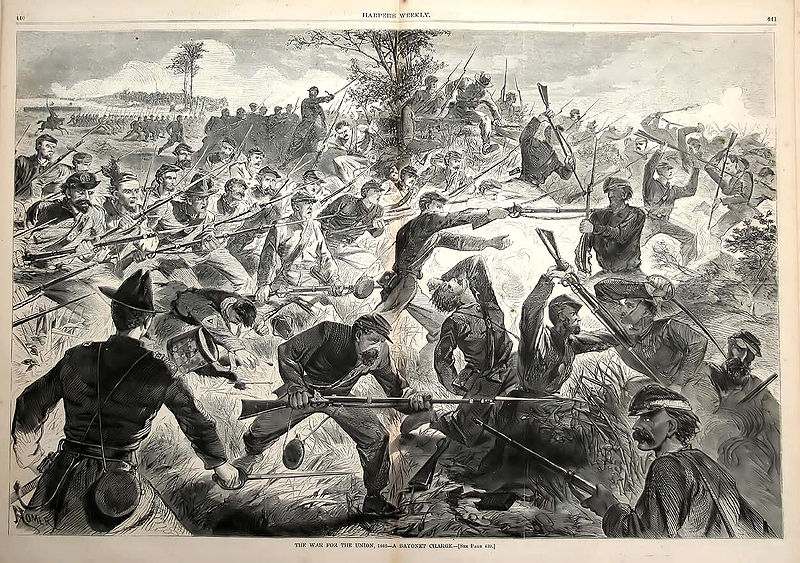

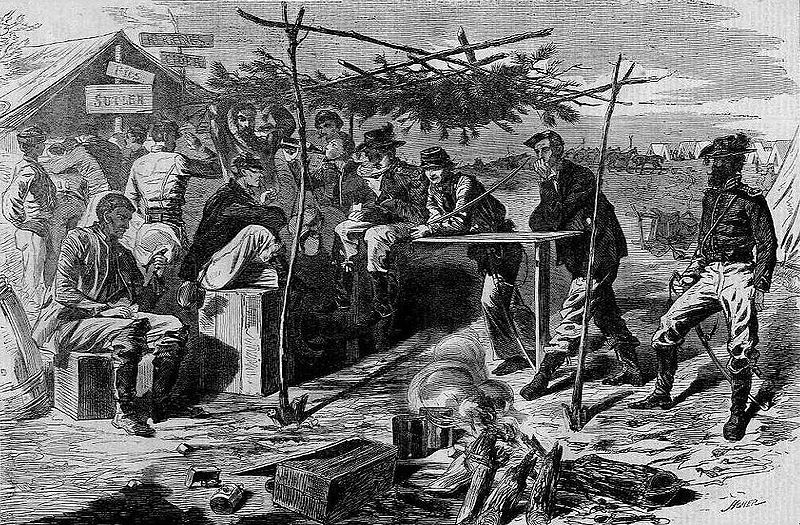

In 1859, he opened a studio in the Tenth Street Studio Building in New York City, the artistic and publishing capital of the United States. Until 1863 he attended classes at the National Academy of Design, and studied briefly with Frédéric Rondel, who taught him the basics of painting. In

only about a year of self-training, Homer was producing excellent oil

work. His mother tried to raise family funds to send him to Europe for

further study but instead Harper's sent Homer to the front lines of the American Civil War (1861 – 1865), where he sketched battle scenes and camp life, the quiet moments as well as the murderous ones. His initial sketches were of the camp, commanders, and army of the famous Union officer, Major General George B. McClellan, at the banks of the Potomac River in October, 1861. Although

the drawings did not get much attention at the time, they mark Homer's

expanding skills from illustrator to painter. Like with his urban

scenes, Homer also illustrated women during war time, and showed the

effects of the war on the home front. The war work was dangerous and

exhausting. Back at his studio, however, Homer would regain his

strength and re-focus his artistic vision. He set to work on a series

of war-related paintings based on his sketches, among them Sharpshooter on Picket Duty (1862), Home, Sweet Home (1863), and Prisoners from the Front (1866). He exhibited Home, Sweet Home at

the National Academy and its remarkable critical reception resulted in

its quick sale and in the artist being elected an Associate

Academician, then a full Academician in 1865. After the war, Homer turned his attention primarily to scenes of childhood and young women, reflecting nostalgia for simpler times, both his own and the nation as a whole. His Crossing the Pasture (1871 – 1872)

depicts two boys who idealize brotherhood with the hope of a united

future after the war that pitted brother against brother. At

nearly the beginning of his painting career, the twenty-seven year old

Homer demonstrated a maturity of feeling, depth of perception, and

mastery of technique which was immediately recognized. His realism was

objective, true to nature, and emotionally controlled. One critic

wrote, “Winslow Homer is one of those few young artists who make a

decided impression of their power with their very first contributions

to the Academy... He at this moment wields a better pencil, models

better, colors better, than many whom, were it not improper, we could

mention as regular contributors to the Academy.” And of Home, Sweet Home specifically,

“There is no clap-trap about it. The delicacy and strength of emotion

which reign throughout this little picture are not surpassed in the

whole exhibition.” “It is a work of real feeling, soldiers in camp

listening to the evening band, and thinking of the wives and darlings

far away. There is no strained effect in it, no sentimentality, but a

hearty, homely actuality, broadly, freely, and simply worked out.” After exhibiting at the National Academy of Design, Homer finally traveled to Paris, France in 1867 where he remained for a year. His most praised early painting, Prisoners from the Front, was on exhibit at the Exposition Universelle in Paris at the same time. He did not study formally but he practiced landscape painting while continuing to work for Harper's, depicting scenes of Parisian life. Homer

painted about a dozen small paintings during the stay. Although he

arrived in France at a time of new fashions in art, Homer's main

subject for his paintings was peasant life, showing more of an

alignment with the established French Barbizon school and the artist Millet than with newer artists Manet and Courbet. Though his interest in depicting natural light parallels that of the early impressionists, there is no evidence of direct influence as he was already a plein-air painter in America and had already evolved a personal style which was much closer to Manet than Monet.

Unfortunately, Homer was very private about his personal life and his

methods (even denying his first biographer any personal information or

commentary), but his stance was clearly one of independence of style

and a devotion to American subjects. As his fellow artist Eugene Benson

wrote, Homer believed that artists “should never look at pictures” but

should “stutter in a language of their own.” Throughout

the 1870s Homer continued painting mostly rural or idyllic scenes of

farm life, children playing, and young adults courting, including Country School (1871) and The Morning Bell (1872).

In 1875, Homer quit working as a commercial illustrator and vowed to

survive on his paintings and watercolors alone. Despite his excellent

critical reputation, his finances continued to remain precarious. His popular 1872 painting, Snap-the-Whip, was exhibited at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, as was one of his finest and most famous paintings Breezing Up (1876). Of his work at this time, Henry James wrote: Many disagreed with James. Breezing Up, Homer’s iconic painting of a father and three boys out for a spirited sail, received wide praise. The New York Tribune wrote,

“There is no picture in this exhibition, nor can we remember when there

has been a picture in any exhibition, that can be named alongside

this.” Visits to Petersburg, Virginia, around 1876 resulted in paintings of rural African American life.

The same straightforward sensibility which allowed Homer to distill art

from these potentially sentimental subjects also yielded the most

unaffected views of African American life at the time, as illustrated in Dressing for the Carnival (1877) and A Visit from the Old Mistress (1876). In 1877, Homer exhibited for the first time at the Boston Art Club with the oil painting, An Afternoon Sun, (owned by the Artist). From 1877 through 1909 Homer exhibited often at the Boston Art Club.

Works on paper, both drawings and watercolors, were frequently

exhibited by Homer beginning in 1882. A most unusual sculpture by the

Artist, Hunter with Dog - Northwoods,

was exhibited in 1902. By that year Homer had switched his primary

Gallery from the Boston based Doll and Richards to the New York City

based Knoedler & Co. Homer

became a member of The Tile Club, a group of artists and writers who

met frequently to exchange ideas and organize outings for painting, as

well as foster the creation of decorative tiles. For a short time, he

designed tiles for fireplaces. Homer's nickname in The Tile Club was "The Obtuse Bard". Other well known Tilers were painters William Merritt Chase, Arthur Quartley, and the sculptor Augustus Saint Gaudens. Homer started painting with watercolors on a regular basis in 1873 during a summer stay in Gloucester, Massachusetts.

From the beginning, his technique was natural, fluid and confident,

demonstrating his innate talent for a difficult medium. His impact

would be revolutionary. Here, again, the critics were puzzled at first,

"A child with an ink bottle could not have done worse." Another

critic said that Homer “made a sudden and desperate plunge into water

color painting”. But his watercolors proved popular and enduring, and

sold more readily, improving his financial condition considerably. They

varied from highly detailed (Blackboard – 1877) to broadly impressionistic (Schooner at Sunset –

1880). Some watercolors were made as preparatory sketches for oil

paintings (as for “Breezing Up”) and some as finished works in

themselves. Thereafter, he seldom traveled without paper, brushes and

water based paints. As

a result of disappointments with women or from some other emotional

turmoil, Homer became reclusive in the late 1870s, no longer enjoying

urban social life and living instead in Gloucester. For a while, he

even lived in secluded Eastern Point Lighthouse (with

the keeper’s family). In re-establishing his love of the sea, Homer

found a rich source of themes while closely observing the fishermen,

the sea, and the marine weather. After 1880, he rarely featured genteel

women at leisure, focusing instead on working women.

Homer spent two years (1881 – 1882) in the English coastal village of Cullercoats, Tyne and Wear.

Many of the paintings at Cullercoats took as their subjects working men

and women and their daily heroism, imbued with a solidity and sobriety

which was new to Homer's art, presaging the direction of his future

work. He wrote, “The women are the working bees. Stout hardy creatures.” His

palette became constrained and sober; his paintings larger, more

ambitious, and more deliberately conceived and executed. His subjects

more universal and less nationalistic, more heroic by virtue of his

unsentimental rendering. Although he moved away from the spontaneity

and bright innocence of the American paintings of the 1860s and 1870s,

Homer found a new style and vision which carried his talent into new

realms. Back

in the U.S. in November 1882, Homer showed his English watercolors in

New York. Critics noticed the change in style at once, “He is a very

different Homer from the one we knew in days gone by”, now his pictures

“touch a far higher plane... They are works of High Art.” Homer’s

women were no longer “dolls who flaunt their millinery” but “sturdy,

fearless, fit wives and mothers of men” who are fully capable of

enduring the forces and vagaries of nature along side their men. In 1883, Homer moved to Prouts Neck, Maine (in Scarborough), and lived at his family’s estate in the remodeled carriage house just seventy-five feet from the ocean. During the rest of the mid 1880s, Homer painted his monumental sea scenes. In Undertow (1886),

depicting the dramatic rescue of two female bathers by two male

lifeguards, Homer’s figures “have the weight and authority of classical

figures”. In Eight Bells (1886),

two sailors carefully take their bearings on deck, calmly appraising

their position and by extension, their relationship with the sea; they

are confident in their seamanship but respectful of the forces before

them. Other notable paintings among these dramatic struggle-with-nature

images are Banks Fisherman, The Gulf Stream, Rum Cay, Mending the Nets, and Searchlight, Harbor Entrance, Santiago de Cuba. Some of these he repeated as etchings. At fifty years of age, Homer had become a “Yankee Robinson Crusoe, cloistered on his art island” and “a hermit with a brush”. These paintings established Homer, as the New York Evening Post wrote, “in a place by himself as the most original and one of the strongest of American painters.” But despite his critical recognition, Homer’s work never achieved the popularity of traditional Salon pictures or of the flattering portraits by John Singer Sargent. Many of the sea pictures took years to sell and Undertow only earned him $400. In

these years, Homer received emotional sustenance primarily from his

mother, brother Charles, and sister-in-law Martha (“Mattie”). After his

mother’s death, Homer became a “parent” for his aging but domineering

father and Mattie became his closest female intimate. In the winters of 1884-5, Homer ventured to warmer locations in Florida, Cuba, and the Bahamas, and did a series of watercolors as part of a commission for Century Magazine.

He replaced the turbulent green storm tossed sea of Prouts Neck with

the sparkling blue skies of the Caribbean, and the hardy New Englanders

with the leisurely Black natives, further expanding his watercolor

technique, subject matter, and palette. His tropical stays inspired and refreshed him in much the same way as Paul Gauguin’s trips to Tahiti. A Garden in Nassau (1885)

is one of the best examples of these watercolors. Once again, his

freshness and originality were praised by critics, but proved too

advanced for the traditional art buyers and he “looked in vain for

profits.” Homer lived frugally, however, and fortunately, his affluent

brother Charles provided financial help when needed. Additionally, Homer found inspiration in a number of summer trips to the North Woods Club, near the hamlet of Minerva, New York, in the Adirondack Mountains.

It was on these fishing vacations that he experimented freely with the

watercolor medium, producing works of the utmost vigor and subtlety,

hymns to solitude, nature, and to outdoor life. Homer doesn’t shrink

from the savagery of blood sports nor the struggle for survival. The

color effects are boldly and facilely applied. In terms of quality and

invention, Homer's achievements as a watercolorist are unparalleled:

"Homer had used his singular vision and manner of painting to create a

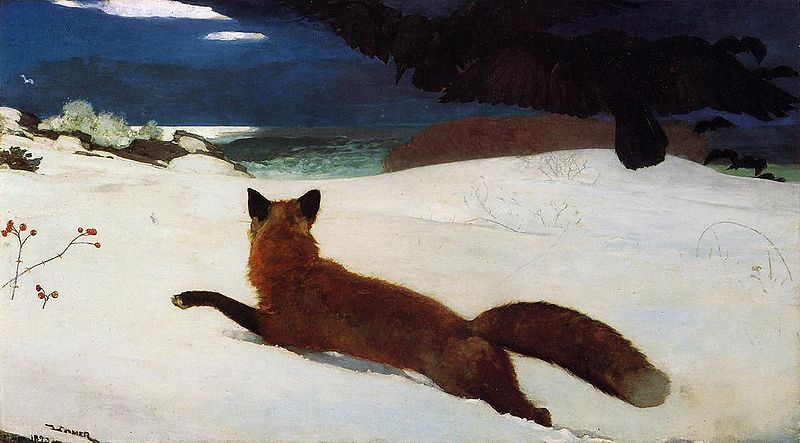

body of work that has not been matched." In 1893, Homer painted one of his most famous “Darwinian” works, The Fox Hunt,

which depicts a flock of starving crows descending on a fox slowed by

deep snow. This was Homer’s largest painting and it was immediately

purchased by the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, his first painting in a major American museum collection. In Huntsman and Dogs (1891),

a lone, impassive hunter, with his yelping dogs at his side, heads home

after a hunt, with deer skins slung over his right shoulder. Another

late work, The Gulf Stream (1899), shows a Black sailor adrift in a damaged boat, surrounded by sharks and an impending maelstrom. By

1900, Homer finally reached financial stability, as his paintings

fetched good prices from museums and he began to receive rents from

real estate properties. He also became free of the responsibilities of

caring for his father who had died two years earlier. Homer

continued producing excellent watercolors, mostly on trips to Canada

and the Caribbean. Other late works include sporting scenes such as Right and Left,

as well as seascapes absent of human figures, mostly of waves crashing

against rocks in varying light. In his last decade, he at times

followed the advice he gave a student artist in 1907, “Leave rocks for

your old age — they’re easy”. Homer died in 1910 at the age of 74 in his Prouts Neck studio and was interred in the Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His painting, Shooting the Rapids, Saguenay River, remains unfinished. His Prouts Neck studio is now owned by the Portland Museum of Art. Homer never taught in a school or privately, as did Thomas Eakins,

but his works strongly influenced succeeding generations of American

painters for their direct and energetic interpretation of man's stoic

relationship to an often neutral and sometimes harsh wilderness. Robert Henri called Homer's work an "integrity of nature." American illustrator and teacher Howard Pyle revered Homer and encouraged his students to study him. His student and fellow illustrator, N.C. Wyeth (and through him Andrew Wyeth and Jamie Wyeth), shared the influence and appreciation, even following Homer to Maine for inspiration. The elder Wyeth’s respect for his antecedent was “intense and absolute,” and can be observed in his early work Mowing (1907). Perhaps Homer's austere individualism is best captured in his admonition to artists: