<Back to Index>

- Aviation Pioneer Louis Charles Breguet, 1880

- Sculptor Christian Daniel Rauch, 1777

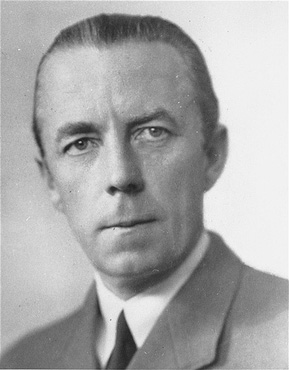

- Diplomat Folke Bernadotte, 1895

PAGE SPONSOR

Folke Bernadotte, Count of Wisborg; in Swedish: Greve af Wisborg (2 January 1895 – 17 September 1948) was a Swedish diplomat and nobleman noted for his negotiation of the release of about 31,000 prisoners from German concentration camps during World War II, including 423 Danish Jews from Theresienstadt released on 14 April 1945. In 1945, he received a German surrender offer from Heinrich Himmler, though the offer was ultimately rejected.

After the war, Bernadotte was unanimously chosen to be the United Nations Security Council mediator in the Arab - Israeli conflict of 1947 - 1948. He was assassinated in Jerusalem in 1948 by the militant Zionist group Lehi, while pursuing his official duties. Folke Bernadotte was born in Stockholm into the House of Bernadotte. He was the son of Count Oscar Bernadotte of Wisborg (formerly Prince Oscar of Sweden, Duke of Gotland) and his spouse Ebba Munck af Fulkila. Bernadotte's grandfather was King Oscar II of Sweden. Bernadotte attended school in Stockholm, after which he entered training to become a cavalry officer at the Military Academy Karlberg. He took the officer's exam in 1915, and was commissioned a lieutenant in 1918, subsequently moving up to the rank of major. Bernadotte represented Sweden in 1933 at the Chicago Century of Progress Exposition, and later served as Swedish commissioner general at the New York World's Fair in

1939 - 40. Bernadotte had long been involved with the Swedish Boy Scouts

(Sveriges Scoutförbund), and took over as director of the

organization in 1937. At the outbreak of World War II, Bernadotte worked to integrate the scouts into Sweden's defense plan, training them in anti-aircraft work and as medical assistants. Bernadotte was appointed vice chairman of the Swedish Red Cross in 1943. While vice-president of the Swedish Red Cross in 1945, Bernadotte attempted to negotiate an armistice between Germany and the Allies.

He also led several rescue missions in Germany for the Red Cross.

During the autumns of 1943 and 1944, he organized prisoner exchanges

which brought home 11,000 prisoners from Germany via Sweden. In April 1945, Heinrich Himmler asked Bernadotte to convey a peace proposal to Prime Minister Winston Churchill and President Harry S. Truman without the knowledge of Adolf Hitler. The main point of the proposal was that Germany would only surrender to the Western Allies (Great Britain and the United States), but would be allowed to continue resisting the Soviet Union.

According to Bernadotte, he told Himmler that the proposal had no

chance of acceptance, but nevertheless he passed it on to the Swedish

government and the Western Allies. It had no lasting effect. Upon the initiative of the Norwegian diplomat Niels Christian Ditleff in the final months of the war, Bernadotte acted as the negotiator for a rescue operation transporting interned Norwegians, Danes and other western European inmates from German concentration camps to hospitals in Sweden. In the spring of 1945, Bernadotte was in Germany when he met Heinrich Himmler,

who was briefly appointed commander of an entire German army following

the assassination attempt on Hitler the year before. Bernadotte had

originally been assigned to retrieve Norwegian and Danish POWs in Germany. He returned on May 1, 1945, the day after Hitler's death. Following an interview, the Swedish newspaper Svenska Dagbladet wrote

that Bernadotte succeeded in rescuing 15,000 people from German

concentration camps, including approximately 8000 Danes and Norwegians

and 7000 women of French, Polish, Czech, British, American, Argentinian

and Chinese nationalities. (SvD 2/5-45). The missions took

approximately two months, and exposed the Swedish Red Cross staff to

significant danger, both due to political difficulties and by taking

them through areas under Allied bombing. The

mission became known for its buses, painted entirely white except for

the Red Cross emblem on the side, so that they would not be mistaken

for military targets. In total it included 308 personnel (approximately

20 medics and the rest volunteer soldiers), 36 hospital buses, 19

trucks, 7 passenger cars, 7 motorcycles, a tow truck, a field kitchen,

and full supplies for the entire trip, including food and gasoline,

none of which were permitted to be obtained in Germany. A count of

21,000 people rescued included 8,000 Danes and Norwegians, 5,911 Poles,

2,629 French, 1,615 Jews and 1,124 Germans. After Germany's surrender,

the White Buses mission continued in May and June to save approximately

10,000 additional people. In total, around 31,000 people were taken to

safety in the "White Buses" of the Bernadotte expedition, including between 6,500 and 11,000 Jews. Bernadotte recounted the White Buses mission in his book The End. My Humanitarian Negotiations in Germany in 1945 and Their Political Consequences,

published on June 15, 1945 in Swedish. In the book, Bernadotte recounts

his negotiations with Himmler and others, and his experience at the Ravensbrück concentration camp. Following

the war, some controversies have arisen regarding Bernadotte's

leadership of the White Buses expedition, some personal and some as to

the mission itself. One aspect involved a long standing feud between

Bernadotte and Himmler's personal masseur, Felix Kersten, who had played some role in facilitating Bernadotte's access to Himmler, but whom Bernadotte resisted crediting after the War. The resulting feud between Bernadotte and Kersten came to public attention through British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper. In 1953, Trevor-Roper published an article based on an interview and documents originating with Kersten. The

article stated that Bernadotte's role in the rescue operations was that

of "transport officer, no more." Kersten was quoted as saying that,

according to Himmler, Bernadotte was opposed to the rescue of Jews and

understood "the necessity of our fight against World Jewry." Shortly

following the publication of his article Trevor-Roper began to retreat

from these charges. At the time of his article, Kersten had just been

nominated by the Dutch government for the Nobel Peace Prize for thwarting a Nazi plan to deport the entire Dutch population, based primarily on Kersten's own claims to this effect. A

later Dutch investigation concluded that no such plan had existed,

however, and that Kersten's documents were partly fabricated. Following these revelations and others, Trevor-Roper told journalist Barbara Amiel in

1995 that he was no longer certain about the allegations, and that

Bernadotte may merely have been following his orders to rescue Danish

and Norwegian prisoners. A

number of other historians have also questioned Kersten's account,

concluding that the accusations were based on a forgery or a distortion

devised by Kersten. Some

controversy regarding the White Buses trip has also arisen in

Scandinavia, particularly regarding the priority given to Scandinavian prisoners. Political

scientist Sune Persson judged these doubts to be contradicted by the

documentary evidence. He concluded, "The accusations against Count

Bernadotte ... to the effect that he refused to save Jews from the

concentration camps are obvious lies" and listed many prominent

eyewitnesses who testified on Bernadotte's behalf, including the World Jewish Congress representative in Stockholm in 1945.

On 20 May 1948, Folke Bernadotte was appointed the United Nations' mediator in Palestine, the first official mediator in the UN's history. This was necessitated by the immediate violence that followed the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine and the subsequent unilateral Israeli Declaration of Independence. In this capacity, he succeeded in achieving an initial truce during the subsequent 1948 Arab - Israeli War and laid the groundwork for the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East. The specific proposals showed the influence of the previously responsible British government, and to a lesser extent the U.S. government. On

28 June 1948, Bernadotte submitted his first formal proposal in secret

to the various parties. It suggested that Palestine and Transjordan be

reformed as "a Union, comprising two Members, one Arab and one Jewish."

He wrote that: "in putting forward any proposal for the solution of the

Palestine problem, one must bear in mind the aspirations of the Jews,

the political difficulties and differences of opinion of the Arab

leaders, the strategic interests of Great Britain, the financial

commitment of the United States and the Soviet Union, the outcome of

the war, and finally the authority and prestige of the United Nations. As

far as the boundaries of the two Members were concerned, Bernadotte

thought that the following "might be worthy of consideration." After

the unsuccessful first proposal, Bernadotte continued with a more

complex proposal that abandoned the idea of a Union and proposed two

independent states. This proposal was completed on September 16, 1948,

and had as its basis seven "basic premises" (verbatim): The proposal then made specific suggestions that included (extracts): Bernadotte's

second proposal was prepared in consultation with British and American

emissaries. The degree to which they influenced the proposal is poorly

known, since the meetings were kept strictly secret and all documents

were destroyed, but

Bernadotte apparently "found that the U.S. - U.K., proposals were very

much in accord with his own views" and the two emissaries expressed the

same opinion. The secret was publicly exposed in October, only nine days before the U.S. presidential elections, causing President Truman great

embarrassment. Truman reacted by making a strongly pro-Zionist

declaration, which contributed to the defeat of the Bernadotte plan in

the UN during the next two months. Also contributing was the failure of

the cease-fire and continuation of the fighting. After Bernadotte's death, his assistant American mediator Ralph Bunche was appointed to replace him. Bunche eventually negotiated a ceasefire, signed on the Greek island of Rhodes.

The

Israeli government criticized Bernadotte's participation in the

negotiations. In July 1948, Bernadotte said that the Arab nations were

reluctant to resume the fighting in Palestine and that the conflict now

consisted of "incidents." A spokesman for the Israeli government

replied: "Count Bernadotte has described the renewed Arab attacks as

'incidents.' When human lives are lost, when the truce is flagrantly violated and the SC defied,

it shows a lack of sensitivity to describe all these as incidents, or

to suggest as Count Bernadotte does, that the Arabs had some reason for

saying no... Such an apology for aggression does not augur well for any

successful resumption by the mediator of his mission." Bernadotte was assassinated on Friday 17 September 1948 by members of the Jewish terrorist Zionist group Lehi (commonly

known as the Stern Gang or Stern Group). A three man 'center' of this

extreme Jewish group had approved the killing: Yitzhak Yezernitsky (the

future Prime Minister of Israel Yitzhak Shamir), Nathan Friedmann (also called Natan Yellin-Mor) and Yisrael Eldad (also

known as Scheib). A fourth leader, Emmanuel Strassberg (Hanegbi) was

also suspected by the Israeli prime minister David Ben-Gurion of being

part of the group that had decided on the assassination. The assassination was planned by the Lehi operations chief in Jerusalem, Yehoshua Zettler. By most accounts, it was carried out by six young members of the Lehi group: Yehoshua Cohen,

Shmuel Rosenblum, David Ephrati, Yitzhak Markovitz, Yehoshua Zettler,

and Meshulam Makover. By other accounts, a three man team ambushed Bernadotte's motorcade in Jerusalem's Katamon neighborhood.

Two of them, Yitzhak Ben Moshe (Markovitz) and Avraham Steinberg, shot

at the tires of the UN vehicles. The third, Yehoshua Cohen,

opened the door of Bernadotte's car and shot him at close range. The

bullets also hit a French officer who was sitting beside him, U.N.

Observer Colonel André Serot.

Both were killed. In the immediate confusion, Col. Serot was mistaken

for Dr. Ralph Bunche, the American aide to Bernadotte. Meshulam

Makover, the fourth accomplice, was the driver of the getaway car. General Åge Lundström, who was in the UN vehicle, described the incident as follows: “In

the Katamon quarter, we were held up by a Jewish Army type jeep placed

in a road block and filled with men in Jewish Army uniforms. At the

same moment, I saw an armed man coming from this jeep. I took little

notice of this because I merely thought it was another checkpoint.

However, he put a Tommy gun through the open window on my side of the

car, and fired point blank at Count Bernadotte and Colonel Serot. I

also heard shots fired from other points, and there was considerable

confusion… Colonel Serot fell in the seat in back of me, and I saw at

once that he was dead. Count Bernadotte bent forward, and I thought at

the time he was trying to get cover. I asked him: 'Are you wounded?' He

nodded, and fell back… When we arrived [at the Hadassah hospital], … I

carried the Count inside and laid him on the bed… I took off the Count's

jacket and tore away his shirt and undervest. I saw that he was wounded

around the heart and that there was also a considerable quantity of

blood on his clothes about it. When the doctor arrived, I asked if

anything could be done, but he replied that it was too late." The murders took place at Ben Zion Guini Square, off Hapalmah Street. The following day the United Nations Security Council condemned

the killing of Bernadotte as "a cowardly act which appears to have been

committed by a criminal group of terrorists in Jerusalem while the

United Nations representative was fulfilling his peace seeking mission

in the Holy Land." After his death, Bernadotte's body was returned to Sweden, where the state funeral was attended by Abba Eban on behalf of Israel. Folke was survived by a widow and a 14 year old son. He was buried at the Northern Cemetery in Stockholm. Lehi leaders initially denied responsibility for the attack. Later Lehi took responsibility for the killings in the name of Hazit Hamoledet (The National Front), a name they copied from a war-time Bulgarian resistance group. The

group regarded Bernadotte as a stooge of the British and their Arab

allies, and therefore as a serious threat to the emerging state of

Israel. Most

immediately, a truce was currently in force and Lehi feared that the

Israeli leadership would agree to Bernadotte's peace proposals, which

they considered disastrous. They did not know that the Israeli leaders had already decided to reject Bernadotte's plans and take the military option. Lehi

was forcibly disarmed and many members were arrested, but nobody was

charged with the killings. Yellin-Mor and another Lehi member,

Schmuelevich, were charged with belonging to a terrorist organization.

They were found guilty but immediately released and pardoned.

Yellin-Mor had meanwhile been elected to the first Knesset. Years later, Cohen's role was uncovered by David Ben-Gurion's biographer Michael Bar Zohar, while Cohen was working as Ben-Gurion's personal bodyguard. The first public admission of Lehi's role in the killing was made on the anniversary of the assassination in 1977. The statute of limitations for murder had expired in 1971. The Swedish government believed that Bernadotte had been assassinated by Israeli government agents. They

publicly attacked the inadequacy of the Israel investigation and

campaigned unsuccessfully to delay Israel's admission to the United

Nations. In

1950, Sweden recognized Israel but relations remained frosty despite

Israeli attempts to console Sweden such as the planting of a Bernadotte Forest by the JNF in Israel. At a ceremony in Tel-Aviv in May 1995, attended by the Swedish deputy prime minister, Israeli Foreign Minister and Labor Party member Shimon Peres issued

a "condemnation of terror, thanks for the rescue of the Jews and regret

that Bernadotte was murdered in a terrorist way," adding that "We hope

this ceremony will help in healing the wound." Ralph Bunche,

Bernadotte's American deputy, succeeded him as U.N. mediator. Bunche

was ultimately successful in bringing about the signing of the 1949 Armistice Agreements, for which he would later receive the Nobel Peace Prize. In 1998, Bernadotte was posthumously awarded one of the first three Dag Hammarskjöld Medals, given to UN peacekeepers who are killed in the line of duty.