<Back to Index>

- Astronomer Charles Piazzi Smyth, 1819

- Poet Pietro Antonio Domenico Trapassi (Metastasio), 1698

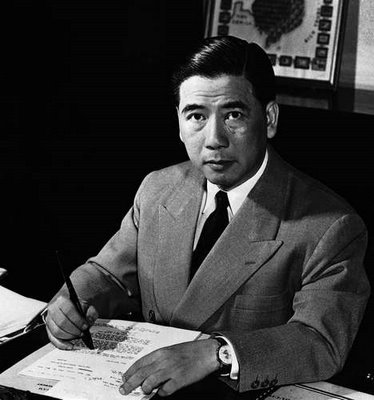

- President of the Republic of Vietnam Ngô Đình Diệm, 1901

PAGE SPONSOR

Ngô Đình Diệm (Vietnamese: Ngô Đình Diệm), (January 3, 1901 – November 2, 1963) was the first President of South Vietnam (1955 – 1963). In the wake of the French withdrawal from Indochina as a result of the 1954 Geneva Accords, Diệm led the effort to create the Republic of Vietnam. Accruing considerable US support due to his staunch anti-Communism, he achieved victory in a 1955 plebiscite that was widely considered fraudulent. Proclaiming himself the Republic's first President, he demonstrated considerable political skill in the consolidation of his power, and his rule proved authoritarian, elitist, nepotistic, and corrupt. A Catholic, Diệm pursued policies that rankled and oppressed the Republic's Montagnard natives and its Buddhist majority. Amid religious protests that garnered worldwide attention, Diệm lost the backing of his US patrons and was assassinated by Nguyen Van Nhung, the aide of ARVN General Dương Văn Minh on November 2, 1963, during a coup d'état that deposed his government. Upon learning of Diệm's ouster and death, Democratic Republic of Vietnam President Ho Chi Minh is reported to have said, "I can scarcely believe the Americans would be so stupid."

Ngô Đình Diệm was born in Huế, the original capital of the Nguyễn Dynasty of Vietnam. Diệm came from the village of Phu Cam in central Vietnam. Portuguese missionaries had converted his family to Roman Catholicism in the 17th century so Diệm was also given a saint's name following the custom of the Catholic Church. Diệm's full name thus became Jean Baptiste Ngô Đình Diệm. Diệm would often claim that he had descended from a blue-blooded family of mandarins who were so revered that people believed that it was a great honour and good luck to be buried alongside his ancestors. Most historians dismiss this as false and believe that his family were of low rank until his father passed the imperial examinations. His father, Ngô Đình Khả, scrapped plans to become a Roman Catholic priest and became a mandarin and counselor to Emperor Thành Thái during the French colonisation. He rose to become the minister of the rites and chamberlain, and keeper of the eunuchs. Khả had six sons and three daughters by his second wife, whom he married after his first died childless. Devoutly Roman Catholic, Khả took his entire family to Mass every morning. The third of six sons, Diệm was christened Jean-Baptiste in the cathedral in Huế. In 1907, the French deposed the emperor on the pretext of insanity because of his complaints about the colonisation. Khả retired in protest and became a farmer. Diệm laboured in the family's rice fields while studying at a French Catholic school, and later entered a private school started by his father. Aged fifteen, he followed his elder brother, Ngô Đình Thục, later to become Vietnam's highest ranking Catholic bishop, into a monastery. After a few months, he left, finding monastic life too rigorous. At the end of his secondary schooling, his examination results at the French lycee in Huế saw him offered a scholarship to Paris but declined to contemplate becoming a priest. He dropped the idea, believing it to be too rigorous. He moved to Hanoi to study at the School of Public Administration and Law, a French school that trained Vietnamese bureaucrats. It was there that he had the only romantic relationship of his life when he fell in love with one of his teacher's daughters. After she jilted him for a convent, he remained celibate.

After graduating at the top of his class in 1921, Diệm followed in the footsteps of his eldest brother Ngô Ðình Khôi, joining the civil service. Starting from the lowest rank of mandarin, Diệm steadily rose. He first served at the royal library in Huế, and within one year was the district chief, presiding over seventy villages. Diệm was promoted to be a provincial chief at the age of 25, overseeing 300 villages. Diệm's rise was helped by Khôi's marriage to the daughter of Nguyễn Hữu Bài, the Catholic head of the Council of Ministers. Bài was highly regarded among the French and Diệm's religious and family ties impressed him. The French were impressed by his work ethic but were irritated by his frequent calls to grant more autonomy to Vietnamese. Diệm said that he contemplated resigning but encouragement from the populace convinced him to persist. He first encountered communists distributing propaganda while riding horseback through the region near Quảng Trị. Diệm involved himself in anti-communist activities for the first time, printing his own pamphlets. In 1929, he helped to round up communist agitators in his administrative area. He was rewarded with the promotion to the governorship of Phan Thiết Province, and in 1930 and 1931 suppressed the first peasant revolts organised by the communists, in collaboration with French forces. During the violent events, many villagers were raped and murdered. In 1933, with the return of Bảo Đại to ascend the throne, Diệm was appointed by the French to be his interior minister following lobbying by Bài. After calling for the French to introduce a Vietnamese legislature, he resigned after three months in office when this was rejected. He was stripped of his decorations and titles and threatened with arrest.

For the next decade, Diệm lived as a private citizen with his family, although he was kept under surveillance. He was to have no formal job for 21 years. He spent his time on reading, meditating, attending church, gardening, hunting and amateur photography. Being a conservative, Diệm was not a believer in revolutions and confined his nationalist activities to occasional trips to Saigon to meet with Phan Bội Châu. With the start of the Second World War in the Pacific, he attempted to persuade the invading Japanese forces to declare independence for Vietnam in 1942 but was ignored. He founded a secret political party, the Association for the Restoration of Great Vietnam. When its existence was discovered in the summer of 1944, the French declared Diệm to be a subversive and ordered his arrest. He fled to Saigon disguised as a Japanese officer. In 1945, the Japanese offered him the premiership of a puppet regime under Bảo Đại which they organised upon leaving the country. He declined initially, but regretted his decision and attempted to reclaim the offer. Bảo Đại had already given the post to another candidate and Diệm avoided the stigma of being a collaborationist. In September 1945 after the Japanese withdrawal, Hồ Chí Minh proclaimed the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, his Việt Minh began fighting the French. Diệm attempted to travel to Huế to dissuade Bảo Đại from joining Hồ, but was arrested by the Việt Minh along the way and exiled to a highland village near the border. He might have died of malaria, dysentery and influenza had the local tribesmen not nursed him back to health. Six months later, he was taken to meet Hồ in Hanoi, but refused to join the Việt Minh, assailing Hồ for the death of his brother Khoi. Khoi had been buried alive by Việt Minh cadres.

Diệm

continued to attempt to gather support for himself on an anti-Vietminh

platform. Despite having little success, Ho was sufficiently irritated

to order his arrest. Diem narrowly evaded arrest but was given respite

in November 1946 when clashes between the French and Vietminh escalated

into full scale war, forcing the Vietminh to divert their resources to

fighting. Diem then moved south to the Saigon region to live with Thuc.

Diem then jointly founded the Vietnam National Alliance, which called for France to grant Vietnam dominion status similar to the Commonwealth of Nations.

The alliance was sufficient to generate support to fund newspapers in

Hanoi and Saigon respectively. Both were shut down; the editor in Hanoi

was arrested and hit men were hired to kill his Saigon counterpart.

Diem's activities had gained him substantial publicity and when France

decided to make concessions to placate nationalist agitators, they

asked him to lobby Bảo Đại to join them. Diem gave up when Bảo Đại made

a deal which he felt to be soft, and returned to Huế. In the meantime,

the French had started the State of Vietnam and

Diem refused Bảo Đại's offer to become the Prime Minister. He then

published a new manifesto in newspapers proclaiming a third force

different to communism and French colonialism, but raised little

interest. In 1950, the Vietminh lost patience, sentenced him to death in

absentia, and the French refused to protect him. Ho's cadres tried to

kill him while he was traveling to visit his elder brother Ngo Dinh Thuc in the Mekong Delta, where he was the bishop of the Vĩnh Long diocese. Diem then left Vietnam in 1950. Diem

applied for permission to travel to Rome for the Holy Year celebrations

at the Vatican. After gaining French permission he left in August with

Thuc, apparently destined to become a politically irrelevant figure.

Before going to Europe, Diem went to Japan, where he intended to meet Cường Để to enlist support to seize power. Neither this nor an attempt to woo help from General Douglas MacArthur, the American supreme commander in occupied Japan, yielded meetings. A friend managed to organise a meeting with Wesley Fishel,

an American academic who had done consultancy work for the US

government. Fishel was a proponent of the anti-colonial, anti-communist

third force doctrine in Asia and was impressed with Diem. He helped

Diem to organise contacts and meetings in the United States to enlist

support. It was an opportune time for Diem, with the outbreak of the Korean War and McCarthyism helping

to make Vietnamese anti-communists a sought after commodity in America.

Diem was given a reception at the State Department with the Acting

Secretary of State James Webb. Possibly intimidated, he gave a weak

performance in which Thuc did much of the talking. As a result, no

further audiences with notable officials were afforded to him. However,

he did meet Cardinal Francis Spellman,

regarded as the most politically powerful cleric of his time. Spellman

had studied with Thuc in Rome in the 1930s and was to become one of

Diem's most powerful advocates. Diem managed an audience with Pope Pius XII in

Rome before further lobbying across Europe. Diem also attempted to

convince Bảo Đại to make him the Prime Minister of the State of Vietnam

but was turned down. Diệm returned to the United States to continue

lobbying and in 1951 was able to secure an audience with Secretary of

State Dean Acheson. During the next three years he lived at Spellman's Maryknoll seminary in Lakewood Township, New Jersey, and occasionally at another seminary in Ossining, New York. Spellman helped Diệm to garner support among right wing and Catholic circles such as that of Joseph McCarthy.

Diem toured the east of America speaking at universities, arguing that

Vietnam could only be saved for the "free world" if the US sponsored a

government of nationalists who were opposed to both the Vietminh and

the French. He was appointed as a consultant to Michigan State University's

Government Research Bureau, where Fishel worked. MSU was administering

government sponsored assistance programs for cold war allies, and Diệm

helped Fishel to lay the foundation for a program later implemented in

South Vietnam, the Michigan State University Vietnam Advisory Group. As French power in Vietnam declined, Diệm's support in America made his stock rise. With the fall of Dien Bien Phu in

1954 to the Vietminh, French control of Vietnam collapsed and Bảo Đại

needed foreign help to sustain his State of Vietnam. Realising Diệm's

popularity among American policymakers, he chose Diệm's youngest brother Ngo Dinh Luyen,

who was studying in Europe at the time, to be part of his delegation at

the 1954 Geneva Conference to determine the future of Indochina. Luyen

represented Bảo Đại in his dealings with the Americans, who understood

this to be an expression of interest in Diệm. With the backing of the Eisenhower administration,

Bảo Đại named Diệm as the Prime Minister. The appointment was widely

condemned by French officials, who felt that Diệm was incompetent, with

the Prime Minister Mendes-France declaring Diệm to be a "fanatic". The

Geneva accords resulted in Vietnam being partitioned temporarily at the

17th parallel, pending elections in 1956 to reunify the country. The

Vietminh controlled the north, while the French backed State of Vietnam

controlled the south with Diệm as the Prime Minister. French Indochina

was to be dissolved at the start of 1955. Diệm's South Vietnamese

delegation chose not to sign the accords, refusing to have half the

country under communist rule, but the agreement went into effect

regardless. Diệm arrived at Tan Son Nhut airport

in Saigon on June 26, where only a few hundred people turned out to

greet him, mainly Catholics. Diệm managed only one wave after getting

into his vehicle and did not smile. He was not a man of the people and

did not intend to become one, being more interested in commanding

respect than popular affection. The

accords allowed for freedom of movement between the two zones until

October 1954; this was to put a large strain on the south. Diệm had

only expected 10,000 refugees, but by August, there were over 200,000

waiting in Hanoi and Haiphong to

be evacuated; the migration helped to strengthen Diệm's political base

of support. Before the partition, the majority of Vietnam's Catholic

population lived in the north. After the borders were sealed, this

majority was now under Diệm's rule. The US Navy program Operation Passage to Freedom saw up to one million North Vietnamese move south, most of them Catholic. The CIA's Edward Lansdale, who had been posted to help Diệm strengthen his rule, led

a propaganda campaign to encourage as many refugees to move south as

possible. This effort was twofold: to strengthen the Catholic

population specifically and the population generally to help win the

1956 reunification elections. This included sending South Vietnamese

agents into the north to spread rumours of impending doom, such as

Chinese invasion and pillaging, hiring soothsayers to predict disaster

under communism, and claiming that the Americans would use nuclear

weapons on North Vietnam. Diệm also used slogans such as "Christ has

gone south" and "the Virgin Mary had departed from the North", alleging

anti-Catholic persecution under Ho Chi Minh. Over 60% of northern

Catholics moved to Diệm's South Vietnam, providing him with a source of

loyal support. Diệm's

position at the time was weak; Bảo Đại disliked Diệm and appointed him

mainly to political imperatives. The French saw him as hostile and

hoped that his rule would collapse. At the time, the French

Expeditionary Corps was the most powerful military force in the south;

Diệm's Vietnamese National Army was essentially organised and trained

by the French. Its officers were installed by the French and the chief

of staff General Nguyen Van Hinh was a French citizen; Hinh loathed Diệm and frequently disobeyed him. Diệm also had to contend with two religious sects, the Cao Dai and Hoa Hao, who wielded private armies in the Mekong Delta,

with the Cao Dai estimated to have 25,000 men. The Vietminh was also

estimated to have control over a third of the country. The situation

was worse in the capital, where the Binh Xuyen organised

crime syndicate boasted an army of 40,000 and controlled a vice empire

of brothels, casinos, extortion rackets, and opium factories

unparalleled in Asia. Bảo Đại had given the Binh Xuyen control of the

national police for 1.25 m USD, creating a situation that the Americans

likened to Chicago under Al Capone in the 1920s. In effect, Diệm's control did not extend beyond his palace. In

August, Hinh launched a series of public attacks on Diệm, proclaiming

that South Vietnam needed a "strong and popular" leader; Hinh bragged

that he was preparing a coup. This was thwarted when Lansdale arranged

overseas holiday invitations for Hinh's officers. Fearing Diệm's

collapse, nine members of his government resigned during Hinh's

abortive bid for power. Despite its failure, the French continued to

encourage Diệm's enemies in an attempt to destabilize him. Diệm's appointment came after the French had been defeated at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu and were ready to withdraw from Indochina. At the start of 1955, French Indochina was dissolved, leaving Diệm in temporary control of the south. A referendum was scheduled for October 23, 1955 to determine the future direction of the south. It was contested by Bảo Đại,

the Emperor, advocating the restoration of the monarchy, while Diệm ran

on a republican platform. The elections were held, with Diệm's brother

and confidant Ngô Đình Nhu, the leader of the family's Can Lao Party, which supplied Diệm's electoral base, organising and supervising the elections. Campaigning

for Bảo Đại was prohibited, and the result was rigged, with Bảo Đại

supporters attacked by Nhu's workers. Diệm recorded 98.2% of the vote,

including 605,025 votes in Saigon, where only 450,000 voters were

registered. Diệm's tally also exceeded the registration numbers in

other districts. Three days later, Diệm proclaimed the formation of the Republic of Vietnam, naming himself President. Under the 1954 Geneva Accords,

Vietnam was to undergo elections in 1956 to reunify the country. Diệm,

noting that South Vietnam was not a party to the convention, canceled

these. Criticising the Communists, he justified the electoral

cancellation by claiming that the 1956 elections would be "meaningful

only on the condition that they are absolutely free", despite his

numerically impossible tally in the 1955 contest. After

coming under pressure from within the country and the United States,

Diệm agreed to hold legislative elections in August 1959 for South

Vietnam. Newspapers were not allowed to publish names of independent

candidates or their policies, and political meetings exceeding five

people were prohibited. Candidates were disqualified for petty reasons

such as acts of vandalism against campaign posters. In the rural areas,

candidates who ran were threatened using charges of conspiracy with the

Vietcong, which carried the death penalty. Phan Quang Dan, the government's most prominent critic, was allowed to run. Despite the deployment of 8,000 ARVN plainclothes troops into his district to vote, Dan still won with a 6–1 ratio. The

busing of soldiers occurred across the country, and when the new

assembly convened, Dan was arrested. Diệm's rule was authoritarian and nepotistic. His most trusted official was his brother, Ngô Đình Nhu, leader of the primary pro-Diệm Can Lao political party, who was an opium addict and admirer of Adolf Hitler. He modeled the Can Lao secret police's marching style and torture styles on Nazi designs. Ngô Đình Cẩn,

his younger brother, was put in charge of the former Imperial City of

Huế. Although neither Cẩn or Nhu held any official role in the

government, they ruled their regions of South Vietnam, commanding

private armies and secret police. Another brother, Ngô Đình Luyện, was appointed Ambassador to the United Kingdom. His elder brother, Ngô Đình Thục, was the archbishop of Huế. Despite this, Thuc lived in the Presidential Palace, along with Nhu, Nhu's wife and Diệm. Diệm was nationalistic, devoutly Catholic, anti-Communist, and preferred the philosophies of personalism and Confucianism. Diệm's rule was also pervaded by family corruption. Can was widely believed to be involved in illegal smuggling of rice to North Vietnam on the black market and opium throughout Asia via Laos, as well as monopolising the cinnamon trade, amassing a fortune stored in foreign banks. With Nhu, Can competed for U.S. contracts and rice trade. Thuc,

the most powerful religious leader in the country, was allowed to

solicit "voluntary contributions to the Church" from Saigon

businessmen, which was likened to "tax notices". Thuc also used his position to acquire farms, businesses, urban real estate,

rental property and rubber plantations for the Catholic Church. He also

used Army of the Republic of Vietnam personnel

to work on his timber and construction projects. The Nhus amassed a

fortune by running numbers and lottery rackets, manipulating currency

and extorting money from Saigon businesses. Luyen became a

multimillionaire by speculating in piasters and pounds on the currency

exchange using inside government information. Madame Nhu, the wife of his brother Nhu, was South Vietnam's First Lady, and she led the way in Diệm's programs to reform Saigon society in accordance with their Catholic values. Brothels and opium dens were

closed, divorce and abortion made illegal, and adultery laws were

strengthened. Diệm also won a street war with the private army of the Binh Xuyen organised

crime syndicate of the Cholon brothels and gambling houses who had

enjoyed special favors under the French and Bảo Đại. He further

dismantled the private armies of the Cao Dai and Hoa Hao religious sects, which controlled parts of the Mekong Delta.

Diệm was also passionately anti-Communist. Tortures and killings of

"communist suspects" were committed on a daily basis. The death toll

was put at around 50,000 with 75,000 imprisonments, and Diệm's effort

extended beyond communists to anti-communist dissidents and

anti-corruption whistleblowers. As

opposition to Diệm's rule in South Vietnam grew, a low-level insurgency

began to take shape there in 1957. Finally, in January 1959, under

pressure from southern cadres who were being successfully targeted by

Diệm's secret police, Hanoi's Central Committee issued a secret

resolution authorizing the use of armed struggle in the South. On 20

December 1960, under instruction from Hanoi, southern communists

established the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam in

order to overthrow the government of the south. The NLF was made up of

two distinct groups: South Vietnamese intellectuals who opposed the

government and were nationalists; and communists who had remained in

the south after the partition and regrouping of 1954 as well as those

who had since come from the north, together with local peasants. While

there were many non-communist members of the NLF, they were subject to

the control of the party cadres and increasingly side-lined as the

conflict continued; they did, however, enable the NLF to portray itself

as a primarily nationalist, rather than communist, movement. The cornerstone of Diệm's counterinsurgency effort was the Strategic Hamlet Program,

which called for the consolidation of 14,000 villages of South Vietnam

into 11,000 secure hamlets, each with its own houses, schools, wells,

and watchtowers. The hamlets were intended to isolate the NLF from the villages, their source of recruiting soldiers, supplies and information. The

communists in southern Vietnam resolved that "if we are able to kill

Ngo Dinh Diem, the leader of the current fascists dictatorial puppet

government, the situation would develop along lines more favourable to

our side." Accordingly, on February 22, 1957, when Diem made a visit to an economic fair in Ban Me Thuot,

a communist cadre named Ha Minh Tri carried out a directive to

assassinate the president. He approached Diem and fired a pistol from

close range, but missed, hitting the Secretary of Agrarian Reform's

left arm. The weapon jammed and security overpowered Tri before he was

able to fire another shot. Diem was unmoved by the incident. There

was an additional attempt to assassinate Ngo (as well as his family) in

1962 when two air force officers —acting in unison — bombed the

presidential palace.

In

1957, Diệm visited the United States and Australia, where he was hailed

as a "leader of the free world". He was widely feted by the media and

politicians of both major parties for his anti-communist convictions.

Diệm was the subject of a failed coup, which occurred in 1960. During the 1946 – 54 war against the French Union forces, the Vietminh,

having gained control of parts of southern Vietnam, initiated land

reform. During the period of war, rent collection, which hovered at

around 50 – 70%, was impossible in some parts of the country, or the

Vietminh had compelled landlords to seek safety in the city and

confiscated their land, distributing it to the peasants. When Diệm came

to power, he reversed these reallocations as upper-class landowners

were part of his ideological support base. In the Mekong Delta, 0.025%

of landowners owned 40% of the land; most of the land was owned by

absentee landlords and worked by tenant farmers. This

generated resentment among the populace, as land ownership was highly

valued by Vietnamese society. Diệm declared that landlords could

collect no more than 25%, but this was not enforced and in some cases

the rent levels were higher than those under French colonisation. Under

U.S. pressure, in 1956, he limited individual land holdings to

1.15 km², and reimbursed the landlords for the excess, which

he sold to peasants. Many landlords evaded the redistribution by

transferring the property to the name of family members. In addition,

the ceiling limit was more than 30 times that allowed in South Korea and Taiwan, and the 370,000 acres (1,500 km2)

of Catholic Church land were exempted. As a result, only 13% of the

South Vietnam's land was redistributed, and by the end of his regime,

only 10% of the tenants had received any land, at a high cost. This

policy failure generated anger, and in turn sympathy to the Vietminh

who had given the peasants free land. At the end of Diệm's rule, 10% of

the population owned 55% of the land. Believing that the central highlands may be of strategic importance to the Vietcong or in a potential invasion by North Vietnam, Diệm decided to construct a Maginot Line of settlements. The area, inhabited by Montagnard indigenous

people, had been largely allowed local autonomy in previous times, and

the locals distrusted ethnic Vietnamese. Diệm initiated a program of

internal migration where 210,000 Vietnamese, mainly Catholics, were

moved to Montagnard land in fortified settlements. When the Montagnards protested, Diệm's forces confiscated their spears and bows, which they used to hunt for daily sustenance. Since then, and to the present day, Vietnam has been faced with a Montagnard insurgent separatist movement. In a country where surveys of the religious composition estimated the Buddhist majority to be between 70 and 90 percent, Diệm's policies generated claims of religious bias. As a member of the Catholic Vietnamese minority,

he is widely regarded by historians as having pursued pro-Catholic

policies that antagonized many Buddhists. Specifically, the government

was regarded as being biased towards Catholics in public service and

military promotions, as well as the allocation of land, business favors

and tax concessions. Diệm also once told a high ranking officer, forgetting that he was a

Buddhist, "Put your Catholic officers in sensitive places. They can be trusted." Many officers in the Army of the Republic of Vietnam converted to Catholicism in the belief that their military prospects depended on it. Additionally,

the distribution of firearms to village self-defense militias intended

to repel Vietcong guerrillas saw weapons only given to Catholics, with

Buddhists in the army being denied promotion if they refused to convert

to Catholicism. Some Catholic priests ran their own private armies, and in some areas forced conversions, looting, shelling and demolition of pagodas occurred. Some Buddhist villages converted en masse in order to receive aid or avoid being forcibly resettled by Diệm's regime. The

Catholic Church was the largest landowner in the country, and the

"private" status that was imposed on Buddhism by the French, which

required official permission to conduct public Buddhist activities, was

not repealed by Diệm. The land owned by the Catholic Church was exempt from land reform. Catholics were also de facto exempt from the corvée labor

that the government obliged all citizens to perform; U.S. aid was

disproportionately distributed to Catholic majority villages. Under

Diệm, the Catholic Church enjoyed special exemptions in property

acquisition, and in 1959, Diệm dedicated his country to the Virgin Mary. The white and gold Vatican flag was regularly flown at all major public events in South Vietnam. U.S. Aid supplies tended to go to Catholics, and the newly constructed Hue and Dalat universities were placed under Catholic authority to foster a Catholic skewed academic environment. The

regime's relations with the U.S. worsened during 1963, as well as

heightening discontent among South Vietnam's Buddhist majority. In May, in the central city of Huế, where Diệm's elder brother was the archbishop, Buddhists were prohibited from displaying Buddhist flags during Vesak celebrations commemorating the birth of Gautama Buddha when the government cited a regulation prohibiting the display of non-government flags.

A few days earlier, Catholics were allowed to fly religious flags at

another celebration where the regulation was not enforced. This led to a protest led by Thich Tri Quang against

the government, which was suppressed by Diệm's forces, killing nine

unarmed civilians. Diệm and his supporters blamed the Vietcong for the deaths and claimed that the protesters were responsible for the violence. Although

the provincial chief expressed sorrow for the killings and offered to

compensate the victims' families, they resolutely denied that

government forces were responsible for the killings and blamed the

Vietcong.

The

Buddhists pushed for a five point agreement: freedom to fly religious

flags, an end to arbitrary arrests, compensation for the Huế victims,

punishment for the officials responsible and religious equality. Diệm

labeled the Buddhists as "damn fools" for demanding something that,

according to him, they already enjoyed. Diệm

banned demonstrations, and ordered his forces to arrest those who

engaged in civil disobedience. On June 3, 1963, protesters attempted to

march towards Tu Dam Pagoda. Six waves of ARVN tear gas and attack dogs

failed to disperse the crowds, and finally brownish red liquid

chemicals were doused on praying protesters, resulting in 67 being

hospitalised for chemical injuries. A curfew was subsequently enacted. The turning point came in June when a Buddhist monk, Thích Quảng Đức,

set himself on fire in the middle of a busy Saigon intersection in

protest of Diệm's policies; photos of this event were disseminated

around the world, and for many people these pictures came to represent

the failure of Diệm's government. A number of other monks publicly self-immolated,

and the U.S. grew increasingly frustrated with the unpopular leader's

public image in both Vietnam and the United States. Diệm used his

conventional anti-communist argument, identifying the dissenters as

communists. As

demonstrations against his government continued throughout the summer,

the special forces loyal to Diệm's brother Nhu conducted an August raid of the Xa Loi Pagoda in

Saigon. The Pagodas were vandalised, monks beaten, the cremated remains

of Thích Quảng Đức, which included a heart which did not

disintegrate, were confiscated. Simultaneous raids were carried out across the country, with the Tu Dam Pagoda in Huế being looted, the statue of Gautama Buddha demolished and a body of a deceased monk confiscated. When the populace came to the defense of the monks, the resulting clashes saw 30 civilians killed and 200 wounded. In

all 1400 monks were arrested, and some thirty were injured across the

country. The U.S. indicated their disapproval of Diệm's administration

when their ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge visited the Pagoda ex post facto. No further mass Buddhist protests occurred during the remainder of Diệm's rule. During this time, Madame Nhu, who was the de facto first

lady because of Diệm's bachelor life, inflamed the situation by

mockingly applauding the suicides, referring to them as "barbecues"

while Nhu stated "If the Buddhists want to have another barbecue, I

will be glad to supply the gasoline." The pagoda raids stoked widespread public disquiet in the previously apolitical Saigon public. Students at Saigon University boycotted classes and rioted, which led to arrests, imprisonments and the closure

of the university; this was repeated at Huế's University. When high

school students demonstrated, Diệm arrested them as well; over 1,000

students from Saigon's leading high school, most of them children of

Saigon public servants, were sent to re-education camps. Children as

young as five were also sent to these camps on charges of

anti-government graffiti. Diệm's foreign minister Vu Van Mau resigned, shaving his head like a Buddhist monk in protest. When he attempted to leave the country on a religious pilgrimage, Diệm had him jailed. On orders from U.S. President John F. Kennedy, Henry Cabot Lodge, the American ambassador to South Vietnam, refused to meet with Diệm. Upon hearing that a coup d'état was being designed byARVN generals led by General Dương Văn Minh,

the United States gave secret assurances to the generals that the U.S.

would not interfere. Dương Văn Minh and his co-conspirators overthrew

the government on November 1, 1963. The coup was very swift. On November 1, with only the palace guard remaining to defend President Diệm and his younger brother, Ngô Đình Nhu,

the generals called the palace offering Diệm exile if he surrendered.

However, that evening, Diệm and his entourage escaped via an

underground passage to Cholon, where they were captured the following morning, November 2. The brothers were executed in the back of an armoured personnel carrier by Captain Nguyen Van Nhung while en route to the Vietnamese Joint General Staff headquarters. Diệm was buried in an unmarked grave in a cemetery next to the house of the U.S. ambassador. Upon learning of Diệm's ouster and death, Ho Chi Minh is reported to have said, "I can scarcely believe the Americans would be so stupid." The

North Vietnamese Politburo was more explicit, predicting: "The

consequences of the 1 November coup d'état will be contrary to

the calculations of the U.S. imperialists ... Diệm was one of the

strongest individuals resisting the people and Communism. Everything

that could be done in an attempt to crush the revolution was carried

out by Diệm. Diệm was one of the most competent lackeys of the U.S.

imperialists ... Among the anti-Communists in South Vietnam or exiled

in other countries, no one has sufficient political assets and

abilities to cause others to obey. Therefore, the lackey administration

cannot be stabilized. The coup d'état on 1 November 1963 will

not be the last." After

Diệm's assassination, South Vietnam was unable to establish a stable

government and numerous coups took place during the first several years

after his death. While the U.S. continued to influence South Vietnam's

government, the assassination bolstered North Vietnamese attempts to

characterize the South Vietnamese as supporters of colonialism.